The deadly shootings on Wednesday at Fort Hood, Texas, were allegedly the act of an Iraqi war veteran who had been under evaluation for post-traumatic stress disorder and was being treated for anxiety and depression, according to the Army. But military officials stressed that the shooter, Specialist Ivan Antonio Lopez, had not seen combat during a relatively short tour in Iraq in 2011, and there are reports of other factors that may have been in play, including a dispute with superiors over a request for leave.

The horrific nature of mass shootings, which are rare and account for a very small share of all homicides, always rivet public attention. But because this one occurred on a military base, it drew attention again to concerns about the extent to how the military copes with soldiers experiencing mental and emotional problems, particularly when it comes to veterans returning from the post-9/11 wars.

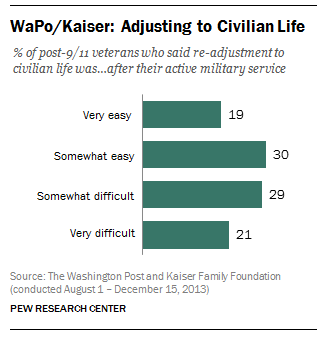

Surveys of veterans by the Washington Post/Kaiser Family Foundation and earlier, by the Pew Research Center, have found common threads in the responses given by these soldiers. Many said they found re-entering civilian life to be difficult. A significant share says they have experienced outbursts of anger in daily life. Others say their mental or emotional health is worse since their time in the service, or that they have suffered post-traumatic stress disorder.

These problems loom at a time when the suicide rate has risen among military personnel, according to a study by the Army and National Institutes of Health and published last March. The Post/Kaiser survey found that half (51%) of the Iraq and Afghanistan veterans it surveyed personally knew a service member or veteran from those wars who had attempted or committed suicide.

The Post/Kaiser survey of 819 veterans, conducted Aug. 1–Dec.15, 2013, found that the experience of war, whether in Iraq or Afghanistan, was still very much on their minds. About six-in-ten (62%) said they thought about it once a week or more, with 33% saying they thought about it every day.

When it came to re-adjusting to civilian life, half of veterans told the Post/Kaiser it was somewhat or very difficult; 49% said it was somewhat or very easy. That was roughly the same as the Pew Research survey found in 2011, with 44% reporting difficulty in readjustment.

Both surveys found sizable shares of returning veterans who experienced bouts of anger or irritability (47% in the Pew Research survey, 41% in the Post/Kaiser’s). About three-in-ten (31%) soldiers in the Post/Kaiser poll said their mental and emotional health was worse since their service, while 56% said it was about the same and 12% deemed it better.

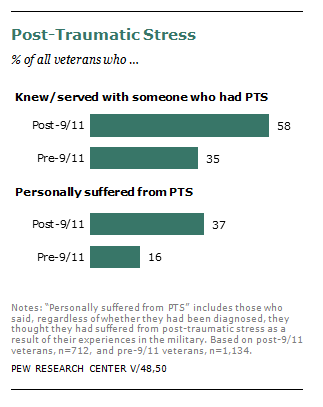

Significant shares (37%) of all post-9/11 war veterans reported suffering from post-traumatic stress syndrome, in the 2011 Pew Research survey.

Notably, these problems have loomed larger for the veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan than for those who served in the wars of the last century.

The Pew Research study, which surveyed 1,853 veterans, found a greater share of post-9/11 veterans than pre-9/11 veterans report that they are carrying psychological and emotional scars arising from their time in the military.

Our results found that the stress and impact of military service took its toll on relationships back home. Among post-9/11 veterans who were married during the time they served, about half (48%) said their deployments had a negative impact on their relationship with their spouse. Among veterans in previous eras who were married while they served, just 34% said the same.

The re-entry problem was also more difficult for the post 9/11 veterans. More than four-in-ten post-9/11 veterans (44%) said they had difficulty readjusting to civilian life, compared with 25% of pre-9/11 veterans. This may be due in part to the fact that post-9/11 veterans are much more likely than those who served before them to have seen combat.