With the Syrian crisis at least temporarily off the federal government’s front burner, Congress is turning its attention back to fiscal issues — most critically, the looming fight over raising the ceiling on federal debt. In Congress, the issue now has become entangled with a stopgap spending measure aimed at averting an Oct. 1 government shutdown, Republican efforts to defund the Affordable Care Act, proposed changes to Social Security and other “entitlement” programs, and a bipartisan effort at overhauling the tax code.

As of the end of August, according to the Treasury Department, government debt was about $25 million shy of the official debt limit of $16,699,421,095,673.60. The government will run out of fiscal wiggle room by mid-October, Treasury Secretary Jacob Lew has warned, meaning that without a change in the law it won’t be able to issue any more debt to keep itself running.

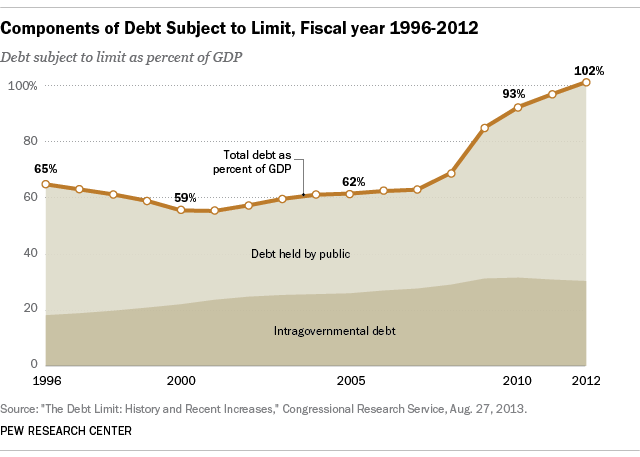

About 28% of the total debt ($4.75 trillion as of the end of August) is held by the Social Security and Medicare trust funds and other governmental accounts; the rest (about $11.95 trillion) is held by the public in the form of various sorts of Treasury securities.

The intra-governmental share of the debt has risen steadily since 1982, as Social Security took in more in payroll taxes than it paid out in benefits and invested the surplus in Treasury bonds. The publicly held portion of the debt is affected by annual budget deficits or surpluses; that portion shrank slightly during the four fiscal years (1998-2001) that the government ran surpluses, but has more than tripled since then, from $3.3 trillion to $11.95 trillion.

Beyond the raw dollar figures, an arguably more useful way to look at the national debt is as a percentage of gross domestic product. Based on the latest GDP estimate the debt currently stands at just over 100% of gross domestic product, its highest level since just after World War II. (It was 55.6% of GDP at the end of fiscal 2001, according to a useful primer prepared by the Congressional Research Service.) That gives the United States one of the higher debt-to-GDP ratios among the 30 developed economies tracked by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, though not the highest: That title goes to Japan, whose public debt is more than twice its GDP.

A Pew Research Center survey in May gave a hint at the difficult negotiations that likely lie ahead. Asked whether it was more important to take steps to reduce the national debt or keep Social Security and Medicare benefits as they are, 53% of respondents chose Social Security and Medicare, while just 36% chose the debt. (A similarly worded question on the deficit, rather than the debt, yielded almost identical results.)