Becoming caught up in a serious ethics scandal isn’t necessarily a career-ender for a member of the U.S. House of Representatives. It turns out only about a quarter exit the political stage through resignation or retirement. The rest choose to seek re-election despite the blot on their records—and two-thirds of them win.

This scandal scorecard comes from a study by three political scientists who examined the re-election fortunes of all members of the House of Representatives who became involved in serious ethics scandals between 1972 and 2006. Their study appears in the latest issue of Social Science Quarterly.

To qualify for their rogue’s gallery, the House Ethics Committee had to open a formal investigation of a member or delay an investigation because of a pending state or federal criminal proceedings against a member. Such action typically comes only after substantial evidence of serious ethical wrongdoing has become publicly known.

In all, a total of 88 members made it into the scandal study, which was conducted by Rodrigo Praino and Vincent G. Moscardelli of the University of Connecticut and Daniel Stockemer of the University of Ottawa.

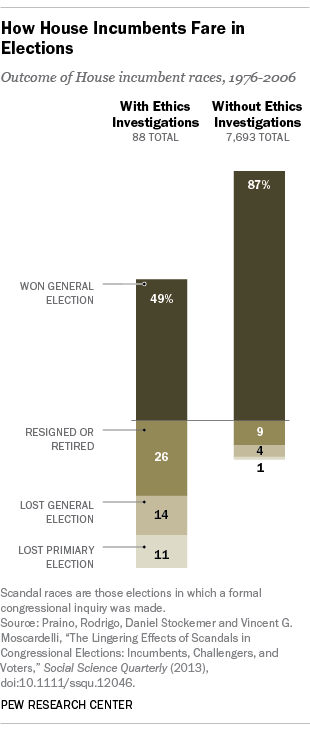

Researchers found that about 26% resigned or retired. About as many (25%) ran for re-election in the next election and lost in the primary or general election.

The remainder—43 representatives, or about half of all members touched by scandal during the study period and two-thirds of those who ran for re-election—were re-elected. In contrast, nearly nine-in-ten incumbents untainted by controversy win their races. (This study does not include disgraced members who leave the House but then run for other offices—think New York Democrat Anthony Weiner, who quit the House after a sexting scandal and is now running for mayor of New York City.)

To be sure, notoriety has its costs, even for politicians. On average, incumbents in scandal races saw their victory margin drop by about 12 percentage points over their last pre-scandal election, the study found. Of course most incumbents win in walk-overs, so the net impact was to drop their average winning margin in scandal races from about 33 percentage points to about 21 points.

Not only that, the effects of scandal linger longer than just one election cycle. These researchers found that politicians gained back about half their lost vote in the next election. And for those who ran again two years later, their average victory margin was back to near 34 points.

A case in point: Rep. Charles Rangel, the New York Democrat who was formally censured, 333 to 79, by his House colleagues in 2010 after a lengthy and well-publicized investigation. A month earlier, Rangel won re-election with 80% of the vote, 9 percentage points below his share in 2008. Last November, Rangel’s winning margin had returned to its pre-scandal average, winning about 90% of the vote after he barely survived a primary challenge.

Rangel was also the first member of Congress to be censured since 1983. According to its report for 2011, the committee began 25 new “investigative matters” in that year and carried over another 26 from the 111th Congress. Many personal indiscretions that produce news headlines but don’t involve violations of House rules never make it to the Ethics Committee and few investigations result in serious disciplinary action.