More than two years after the COVID-19 vaccines were widely available for adults in the United States, Americans provide mixed assessments of the value and potential risks of these vaccines.

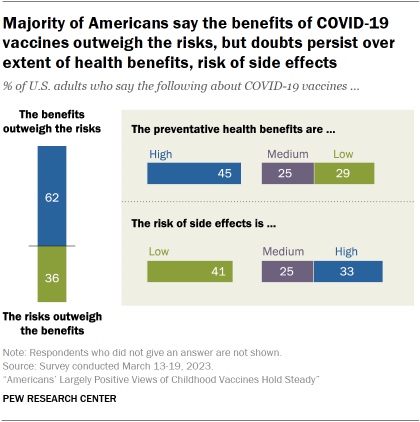

Overall, a majority of Americans believe the benefits of the coronavirus vaccines outweigh the risks and tend to align with the idea that COVID-19 vaccines have saved millions of lives. At the same time, fewer than half consider the preventative health benefits of the vaccines to be high and more describe the risk of side effects as medium or high than view them as low.

How people evaluate the benefits and risks from these vaccines is strongly tied with the choices they have made about getting vaccinated. And for parents, their attitudes and actions also line up closely with the choices they have made for their minor children.

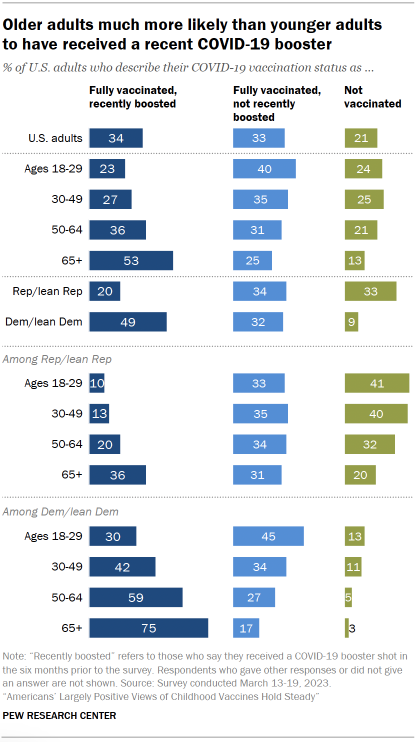

In a sign of limited public enthusiasm for COVID-19 vaccines, only about a third of U.S. adults have the highest level of available protection against the coronavirus, saying they have been fully vaccinated and have received a booster shot within the last six months. (Booster shots designed for newer variants of the coronavirus have been available since September 2022, about six months before the survey was conducted.) A similar share say they were fully vaccinated but have not received a booster shot in the past six months and about a fifth of U.S. adults say they have not been vaccinated against COVID-19.

The unprecedented speed of development for the coronavirus vaccines was widely hailed as an achievement for science. But the public’s comfort with the long-term impacts of these vaccines still has much room to grow. A majority of Americans continue to say the statement “we don’t really know yet if there are serious health risks from COVID-19 vaccines” describes their views very or somewhat well. This view is about as widely held today as it was in August 2021, less than a year after vaccines became widely available.

In-depth qualitative interviews with people who express some concerns around these vaccines highlight the salience of questions about their long-term safety. For other interviewees, concern about risk of side effects is coupled with a view that there is little to gain from getting a COVID-19 vaccine either because they see themselves at low risk of serious harm from the 62% of Americans say positives of COVID-19 vaccines outweigh negatives, though sizable shares see modest health benefits and meaningful risks or because the vaccine does not prevent infection from the disease.

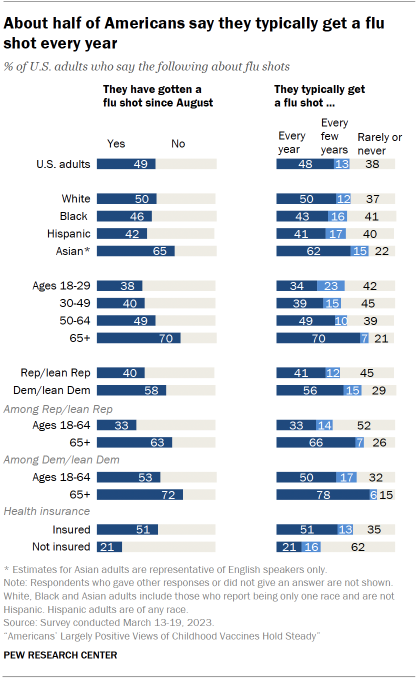

People’s practices related to getting a flu vaccine each year tend to align with their choices around getting the coronavirus vaccine. And, as with the coronavirus vaccine, older adults are more likely to say they get a flu shot regularly.

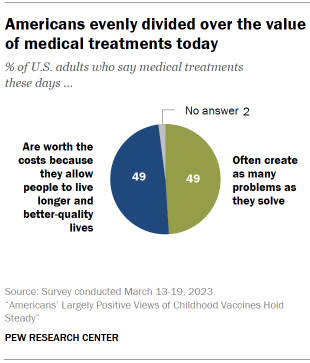

More broadly, Americans are evenly divided over medical treatments today, with about half saying that treatments today are worth the costs because they allow people to live longer, better lives while the other half says that medical treatments these days often create as many problems as they solve. Most Americans agree, however, that the cost of quality medical treatments today is a big problem.

62% of Americans say positives of COVID-19 vaccines outweigh negatives, though sizable shares see modest health benefits and meaningful risks

Overall, 62% of U.S. adults say that the benefits of COVID-19 vaccines outweigh the risks, while a much smaller share think the risks outweigh the benefits (36%).

Even so, when asked to rate the preventative health benefits of COVID-19 vaccines from very high to very low, fewer than half of Americans (45%) rate the benefits as high. More say their benefits are either medium (25%) or low (29%).

When it comes to evaluating the risk of side effects, 58% of Americans rate the risk as high (33%) or medium (25%), while a smaller share (41%) see the risk as low.

People’s ratings of the benefits and risks of coronavirus vaccines are strongly aligned with their own choices related to getting the vaccines. For instance, 64% of those who see the preventative health benefits as very high are fully vaccinated and recently boosted within the past six months, compared with much smaller shares of those who rate the health benefits as medium or low.

Partisan divisions have been prominent in views of the country’s handling of the coronavirus outbreak, as well as in assessments of COVID-19 vaccines themselves. Democrats are about twice as likely as Republicans to say the benefits of coronavirus vaccines outweigh the risks (84% vs. 40%). Similarly, Democrats are much more likely than Republicans to rate the preventative health benefits of COVID-19 vaccines as high (67% to 23%). And 74% of Republicans rate the risk of side effects as at least medium compared with a smaller share of Democrats (42%).

Upper-income adults and those with a four-year college degree also tend to be more positive in their assessments of COVID-19 vaccines than other adults. For example, 71% of upper-income Americans say the benefits of COVID-19 vaccines outweigh the risks, compared with 61% of lower-income Americans. For more, refer to Appendix B.

34% of U.S. adults say they have had a recent booster shot; about as many say they are fully vaccinated but have had no recent booster

The rise of the omicron variant of COVID-19 spurred the development of bivalent booster shots designed to offer better protection from this strain of the coronavirus. These updated boosters were widely available to U.S. adults in September 2022, about six months before the Center survey was conducted. Uptake of these new boosters was reportedly slow last fall when they first became available.

About one-third of U.S. adults (34%) say they are fully vaccinated and have received a booster shot in the last six months. A similar share (33%) say they are fully vaccinated for COVID-19 but have not received a recent booster shot. About one-in-five U.S. adults (21%) say they have not received a COVID-19 vaccine. (Another 7% report having received one shot but would need one more to be fully vaccinated.)

The oldest Americans are more likely to report having received a recent booster and are much less likely to be unvaccinated than younger adults. Among adults ages 65 and older, 53% say they have received a recent booster. Another 25% of this group say they were fully vaccinated but have not received a recent booster. Just 13% say they have not gotten a COVID-19 vaccine.

For comparison, 23% of adults ages 18 to 29 say they have received a recent booster, while 40% say they are fully vaccinated but have not gotten a recent booster shot and another 24% say they have not been vaccinated.

There are wide differences between political parties when it comes to COVID-19 vaccination status, as well as differences within each party group by age, consistent with past Center findings.

Overall, 49% of Democrats say they have had a recent booster shot. Another 32% say they are fully vaccinated but have not had a recent booster and just 9% of Democrats say they were not vaccinated. By contrast, just 20% of Republicans say they have received a recent booster shot; 34% say they are fully vaccinated but have not received a booster and 33% say they did not get a COVID-19 vaccine.

Within each party, adults ages 50 and older are more likely than their younger counterparts to say they are fully vaccinated and have received a recent booster shot. Age differences are particularly wide among Democrats. Three-quarters of Democrats ages 65 and older say they are fully vaccinated and have had a recent booster shot. Among Democrats ages 18 to 29, 30% say they have done this.

While Republicans overall are much less likely than Democrats to say they have received a recent booster shot, age differences also exist within the GOP. For instance, Republicans ages 65 and older are more likely to say they are recently boosted (36%) than those ages 18 to 29 (10%).

Children’s coronavirus vaccination status is closely tied to their parent’s status

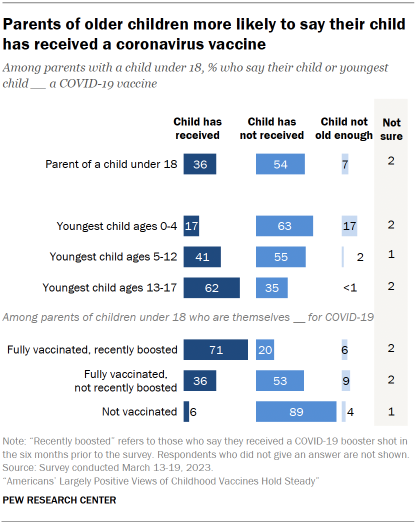

The Center survey asked parents of minors about their child’s COVID-19 vaccination status. In all, 36% of these parents report that their child or youngest child has received a coronavirus vaccine.

Parents of older children are more likely than those with young children to report that their child is vaccinated. A 62% majority of parents of teens (ages 13 to 17) say their child is vaccinated. In contrast, just 17% of parents of children ages 0 to 4 say this.

Vaccines have been available for older children longer than for younger children. Older teens – those ages 16 and 17 – became eligible for one of the coronavirus vaccines at the same time as adults in December 2020. Children and teens ages 12 to 15 became eligible in May 2021. Later that fall, in November 2021, children ages 5 to 11 could receive a coronavirus vaccine. A coronavirus vaccine for younger children – those ages 6 months to 5 years – was not available until June 2022.

Access to COVID-19 vaccines for young children is more limited than for older children, as many pharmacies have minimum age requirements for vaccine eligibility and only some pediatricians administer COVID-19 vaccines to young children. By comparison, pharmacies have been one of the main distribution points for vaccines given to older children as well as adults.

There’s a strong connection between a parent’s own COVID-19 vaccination status and the decision they have made for their child. Most parents who are fully vaccinated and have recently gotten a booster (71%) say their child has received a coronavirus vaccine. In contrast, just 6% of parents who are not vaccinated say their child has received a coronavirus vaccine.

Americans’ appreciation, ambivalence both evident in the sentiments they use to describe COVID-19 vaccines

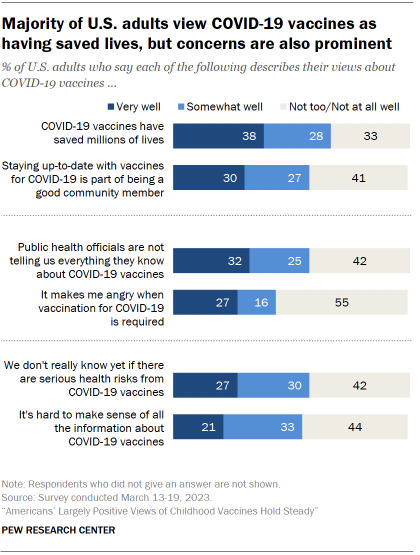

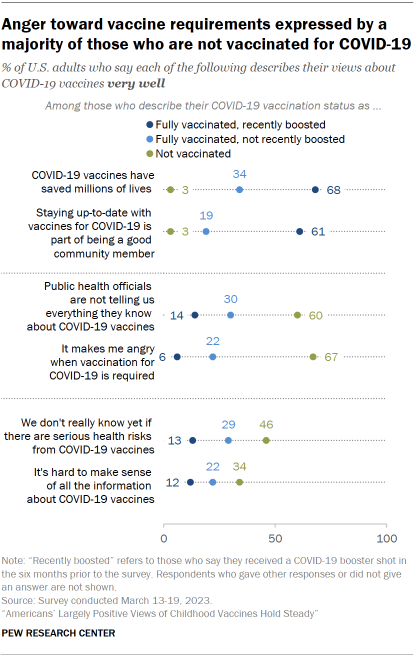

Public views about COVID-19 vaccines remain complex, as evidenced by the mix of sentiments Americans apply to them. About two-thirds (66%) say that the statement “COVID-19 vaccines have saved millions of lives” describes their views very or somewhat well. A majority (57%) also say “staying up-to-date with vaccines for COVID-19 is part of being a good community member” describes how they feel at least somewhat well.

At the same time, many Americans worry that information about COVID-19 vaccines has been held back. A 56% majority say “public health officials are not telling us everything they know about COVID-19 vaccines” describes their views very or somewhat well.

Americans also express concerns about serious risks coming to light in the future. A majority (57%) say the statement “we don’t really know yet if there are serious health risks from COVID-19 vaccines” describes how they feel at least somewhat well.

Underscoring challenges interpreting guidance about vaccines, 55% say the statement “it’s hard to make sense of all the information about COVID-19 vaccines” describes their views very or somewhat well.

Compared with other sentiments included in the survey, a somewhat smaller share of Americans (44%) say the statement “it makes me angry when vaccination for COVID-19 is required” describes their own views very or somewhat well.

There’s been little change since August 2021 regarding public concerns over information about COVID-19 vaccines and concerns about future health impacts. The shares expressing a sense that public health officials are withholding information, uncertainty over potential serious risks from the vaccines, and difficulties making sense of information about vaccines are all roughly the same as those captured in a 2021 Center survey.

The sentiments Americans use to describe COVID-19 vaccines are strongly connected with their own choices about getting the shots.

Fully vaccinated and boosted Americans tend to hold positive views of the vaccines’ value and are much less likely to express concerns about them than other adults. Among this group, 68% say the statement “COVID-19 vaccines have saved millions of lives” describes their views very well and 61% say the same about staying up-to-date with COVID-19 vaccines as part of being a good community member.

Those who have not been vaccinated for COVID-19 are much less inclined to see the vaccines as having saved millions of lives (just 3% say this describes their views very well). A majority of those who have not been vaccinated say it makes them angry when COVID-19 vaccines are required (67% say this describes their views very well) and nearly as many (60%) say the idea that public health officials are not telling us everything they know about the vaccines describes their views very well.

In addition, 46% of those who have not gotten a COVID-19 vaccine say the statement “we don’t really know yet if there are serious health risks from COVID-19 vaccines” describes their views very well; roughly two-thirds (66%) say this describes their views very or somewhat well.

People who have been fully vaccinated but have not received a recent booster in the past six months fall somewhere in the middle, with a mix of positive and negative views about the coronavirus vaccines. For example, a majority of this group (72%) sees the statement that “COVID-19 vaccines have saved millions of lives” as being at least somewhat in line with their views. At the same time, a majority of this group (63%) also says the statement “we don’t really know if there are serious health risks from these vaccines” describes their views at least somewhat well.

Fewer than a third of Americans now express concern about getting a serious case of COVID-19

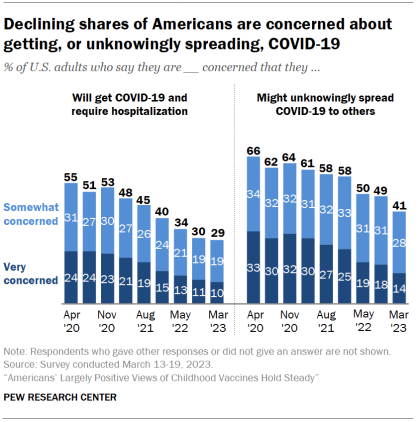

Personal concern about getting a serious case of COVID-19 has gradually declined since November 2020. In the new survey, 29% of Americans are very or somewhat concerned that they will get COVID-19 and require hospitalization. This share is down 24 percentage points from November 2020.

Concern about unknowingly spreading COVID-19 has also declined since the first year of the coronavirus outbreak, though it remains somewhat higher than personal concern about getting a serious case. About four-in-ten U.S. adults (41%) say they are at least somewhat concerned they might unknowingly spread COVID-19 to others. This is a decrease of 23 points from November 2020 and 8 points from September 2022, the last time the Center asked this question.

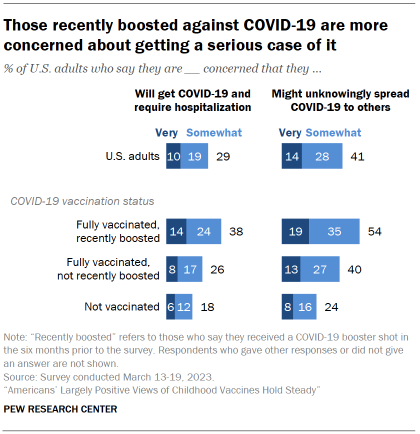

As Center surveys found earlier in the coronavirus outbreak, people who have not been vaccinated express less concern about getting a serious case of the disease (or unknowingly spreading it) than those who have received a vaccine.

Those who are recently boosted and fully vaccinated against COVID-19 are the most likely to be concerned about getting a serious case of the disease.

Among this group, 38% say they are very or somewhat concerned they will get COVID-19 and require hospitalization and 54% say they are at least somewhat concerned about unknowingly spreading the disease to others.

Beyond vaccination status, lower family incomes and the lack of health insurance are associated with higher levels of concern about getting a serious case of COVID-19. And Black, Hispanic and English-speaking Asian adults all express higher levels of concern than White adults. For more, refer to Appendix B.

In-depth interviews reveal ongoing concerns about safety of COVID-19 vaccines and frustrations over requirements to get them

To better understand concerns about COVID-19 vaccines, the Center conducted in-person, qualitative interviews across four U.S. cities with 22 adults who hold some level of vaccine hesitancy.

Many of the interview participants raised concerns about the rapid development of COVID-19 vaccines, the potential for long-term side effects, and the limited period of time for which these vaccines have been tested for potentially adverse effects. Asked about the safety of the COVID-19 vaccines, some participants described their views in the following ways:

“And it hasn’t been around long, and I just feel like a test dummy for it, along with everybody else that got it.” – Woman, age 35-44, Jacksonville, Florida

“I think it’s not that well-tested. So with the kids, we usually get the vaccines. They’ve been out there for a long time and they still have some type of side effects. … So I don’t see how something developed in six months could be totally safe.” – Man, age 50-54, Cincinnati, Ohio

Another who said that he had few concerns about the safety of the coronavirus vaccines for himself questioned how the new vaccines could be safe for those with underlying health conditions:

“I mean, you can’t do a long-term test in a year, right, as quickly as they got them out. For people like that, I was more concerned than myself, who have some sort of underlying health issue that they just can’t run a long-term effect on how this vaccine is going to affect a person with that health.” – Man, age 25-34, Jacksonville, Florida

Interviewees were asked to share any particular concerns they had about the safety of coronavirus vaccines. Some referenced information they had heard from family and friends about a range of side effects from being sick for a few days to more serious side effects like developing Bell’s palsy or having “mini strokes.” And several interviewees mentioned concerns about myocarditis or pointed to the NFL player who collapsed on the field during a game as a possible side effect from the COVID-19 vaccines. (NFL player Damar Hamlin has confirmed the cause of his collapse was commotio cordis, a rare cause of cardiac arrest that can occur following a blow to the chest.)

Concerns about serious side effects from the COVID-19 vaccines loomed large in participants’ thinking about whether or not their child should be vaccinated.

“So I feel like there’s more concern for side effects in her because she’s still growing. And if something truly did go wrong then I would rather have those issues upon me than on her. So let’s do the sample test on me first before giving it to her.” – Man, age 35-44, Seattle, Washington

“It’s too quick. You got young kids, they have their whole life. If they found out at 18 that they had myocarditis problems or something like that, you would feel awful as a parent if you gave your child that shot.” – Man, age 35-44, Cincinnati, Ohio

For some interviewees, concerns about the potential long-term side effects from the COVID-19 vaccines were also rooted in a sense that the vaccines have done little to limit the spread of the coronavirus or have limited personal value for their own health. Some in this group saw their health history as putting them at low risk for getting a serious case of the disease or felt they have natural immunity from having had COVID-19 in the past.

Participants expressed a range of views about how much they value information from doctors and other health care providers about COVID-19 vaccines

Interview participants who spoke positively of information from doctors or other health care providers about the COVID-19 vaccines tended to have a specific, personal relationship in mind. And some found mixed advice from those sources:

“Who do I trust personally? My uncle who’s a doctor, and every step of the way I’ve asked him questions because he’s not on either side of the fence. He’s very just factual, fact based.” – Man, age 50-64, Jacksonville, Florida

“I have friends who are physicians who are completely against it. I have friends who are physicians who are completely fine with it. And then I’ve talked to nurses and other people who are literally on the front lines in hospitals and have been and they’re saying, ‘Well, we don’t trust it yet.’” – Man, age 25-34, Phoenix, Arizona

But some interviewees with concerns about the COVID-19 vaccines gave no special credibility to information from doctors or other medical professionals. As one woman put it:

“[Doctors are] not very credible because, again, that’s the personal opinion of the doctor. So if this doctor believes in it and this doctor doesn’t, and you go see this doctor and I go see this one, then we’ve got two different information. Everybody has, like I said, their formed opinions.” – Woman, age 25-34, Phoenix, Arizona

Another woman raised questions about the motives of many doctors, saying:

“I think a lot of doctors [support the vaccine] because they get people visiting from pharmaceutical companies that are trying to push things, sell their pharmaceuticals.”

– Woman, age 50-54, Phoenix, Arizona

On a broader question about who participants turned to for reliable information about the COVID-19 vaccines, several interviewees talked about relying on family, friends and other sources they see as having trustworthy motives.

“It just doesn’t feel like you can ever trust what information you’re getting, because you can look at one source and they’ll tell you one thing, and then you look at another source that seems to be just as credible as the first source and they’ll tell you the exact opposite thing. So yeah, it’s really hard to make decisions based on that, and that’s why I try to make my decisions based on just my circle of people that I know, as much as I can trust that and as educated as we might be on making those decisions. It’s hard to trust reliability from outside sources, because it feels like we get contradictory information all the time.” – Man, age 35-44, Phoenix, Arizona

“I would say medical studies where people are just really trying to understand it and they’re not coming at it with an agenda. So I would believe that.” – Woman, age 50-54, Phoenix, Arizona

“I think generally the CDC is a good source of information. But again, I think we’re just kind of in an age where there’s too much information out there, information and misinformation. It all depends on whose spin you see on it. That makes it kind of tough for them, I’m sure.” – Man, age 50-64, Jacksonville, Florida

Interviewees expressed frustration over polarized conversations about COVID-19 vaccines, and for some, lasting resentment over feeling forced to get vaccinated

One of the overarching themes that emerged from these conversations was frustration about the polarized environment in the U.S. around vaccines. Several of the interviewees mentioned these divides over the vaccines and the difficulty of having an open conversation about their concerns and decisions.

“You just feel separate from others, just because you chose not to get the shot.” – Woman, age 35-44, Cincinnati, Ohio

“People aren’t open-minded to the people that don’t believe in it. … Some people are just so close-minded, that they think that because the people on TV are telling you to get it, that you’re supposed to get it. I think that’s what bothered me the most. It was like, I have an opinion, I do my own research, I talk to my doctor, and just because they tell you to get it doesn’t mean you just run right out and get it.” – Woman, age 50-54, Cincinnati, Ohio

Several interviewees also pointed to feeling pressured to get vaccinated, whether explicitly or implicitly, as well as their frustration that government spokespeople and others have not fully owned up to changing information about the health risks and benefits of the COVID-19 vaccines.

“And it’s like, ‘No, and it should be my choice.’ You know, my body, my choice, kind of a thing.” – Woman, age 25-34, Phoenix, Arizona

“It just the fact that it was being pushed on everybody, push, push, push. In my mind it was all crap because A, I’d already had the virus or I’d already … Yeah, I’d already had the virus, so I already had natural immunity. There was no way that I needed it, even if I came down …” – Man, age 50-64, Jacksonville, Florida

“I think they should be honest with who actually needs it.” – Man, age 35-44, Cincinnati, Ohio

“Well, there’s probably a lot that bothers me, but I think the thing that bothers me the most is how if we can’t as a society admit that we were wrong about something, or that the data changed and maybe some of our decisions should change, and so one side of the aisle or the other side had decided on something, they weren’t going to let up.” – Man, age 35-44, Cincinnati, Ohio

Older Americans more likely to say they have had a flu shot this season

About half of Americans (49%) report they have gotten a flu shot since August. A similar share (48%) say they typically get a flu shot every year while 13% say they do so every few years and 38% of Americans say they rarely or never get a flu shot.

Older Americans are particularly likely to say they got a flu shot this year. Seven-in-ten adults ages 65 and older say they have gotten a flu shot this season, compared with 38% of those ages 18 to 29. These age patterns are consistent with those seen in past Center surveys.

Health insurance status is also related. Those with health insurance coverage are more likely than those without it to get a flu shot (51% vs. 21%).

These patterns are generally consistent with other studies looking at the factors related to getting a flu vaccine.

There is a strong relationship between Americans’ practices around getting an annual flu shot and their COVID-19 vaccination status, with those fully vaccinated and recently boosted for COVID-19 the most likely to say they regularly get a flu shot.

Americans are divided over the value of medical treatments today

The Center survey also included questions measuring the public’s broad views about medical treatments and their sense of possible problems in health and medical care today.

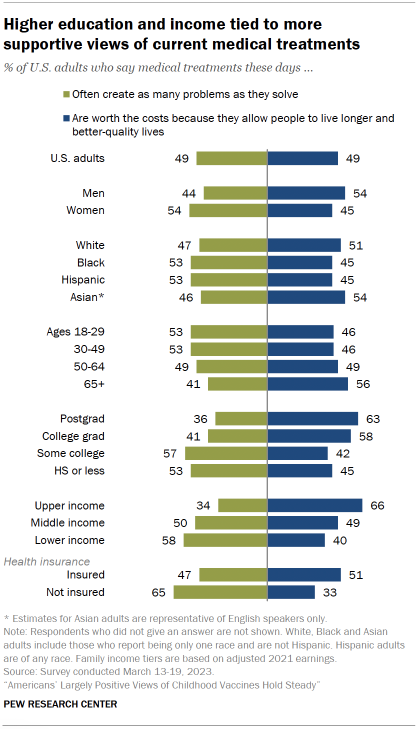

Overall, Americans are evenly divided over the value of current medical treatments: 49% say medical treatments are worth the costs because they allow people to live longer and better-quality lives, while the same share says these treatments often create as many problems as they solve. Views on this issue are about the same as a 2018 Center survey.

Views about the overall value of medical treatments these days are closely tied to family income levels and health insurance status.

Two-thirds of upper-income Americans say medical treatments these days are worth the costs because they allow people to live longer, better-quality lives. Only 34% of upper-income Americans say medical treatments often cause as many problems as they solve. In contrast, 58% of lower-income Americans say medical treatments often cause as many problems as they solve.

Those with no health insurance – a group that’s more likely than others to have lower family incomes — are also more inclined to see medical treatments as creating as many problems as they solve; about two-thirds (65%) take this position while a third say that medical treatments are worth the costs because they allow people to live longer, better-quality lives.

Men are modestly more likely than women to say medical treatments are worth the costs because they allow people to live longer and better-quality lives (54% vs. 45%).

Adults ages 65 and older are more likely than younger adults to emphasize the benefits of medical treatments these days, although these differences are relatively modest. In all, 56% of those ages 65 and older say that medical treatments are worth the costs compared with 46% of those under 30.

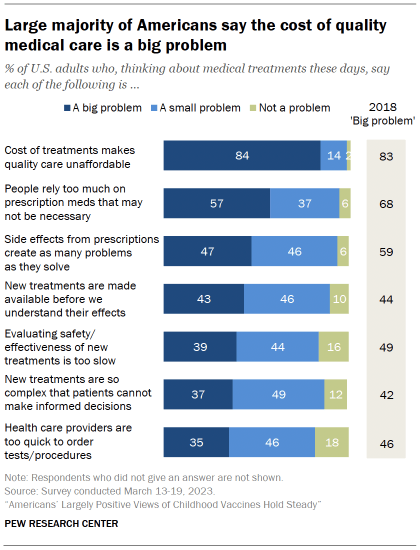

Costs continue to rank at the top of Americans’ list when it comes to problems with medical treatments today.

Asked to rate a series of possible problems in getting medical treatments, 84% of U.S. adults say it is a big problem that the cost of treatments makes quality medical care unaffordable. Just 14% say this is a small problem and 2% say this is not a problem.

A similar share (83%) said costs were a big problem in a 2018 Center survey.

A majority of Americans (57%) also say people relying too much on prescription medications that may not be necessary is a big problem these days. The share who consider this a big problem is down 11 percentage points from 2018, however.

Other concerns are less widely shared: 47% of U.S. adults say it is a big problem that side effects from medical treatments create as many problems as they solve and 43% call it a big problem that new treatments are made available before we understand their effects.

Problems that rank lower for the public include the idea that evaluating the safety and effectiveness of new treatments is too slow (39% say this is a big problem), that new treatments are so complex patients cannot make informed decisions (37% say this is a big problem) and that health care providers are too quick to order tests and procedures that may not be necessary (35% say this is a big problem).