Belief in life after death is widespread around the globe, as is the belief that spirits can reside in animals and in parts of nature such as mountains, rivers or trees, according to a Pew Research Center survey of three dozen countries with a wide range of religious traditions.

Moreover, the new survey shows that younger adults are at least as likely as older adults to hold these spiritual beliefs – unlike belief in God, which tends to be more common among older people, globally.

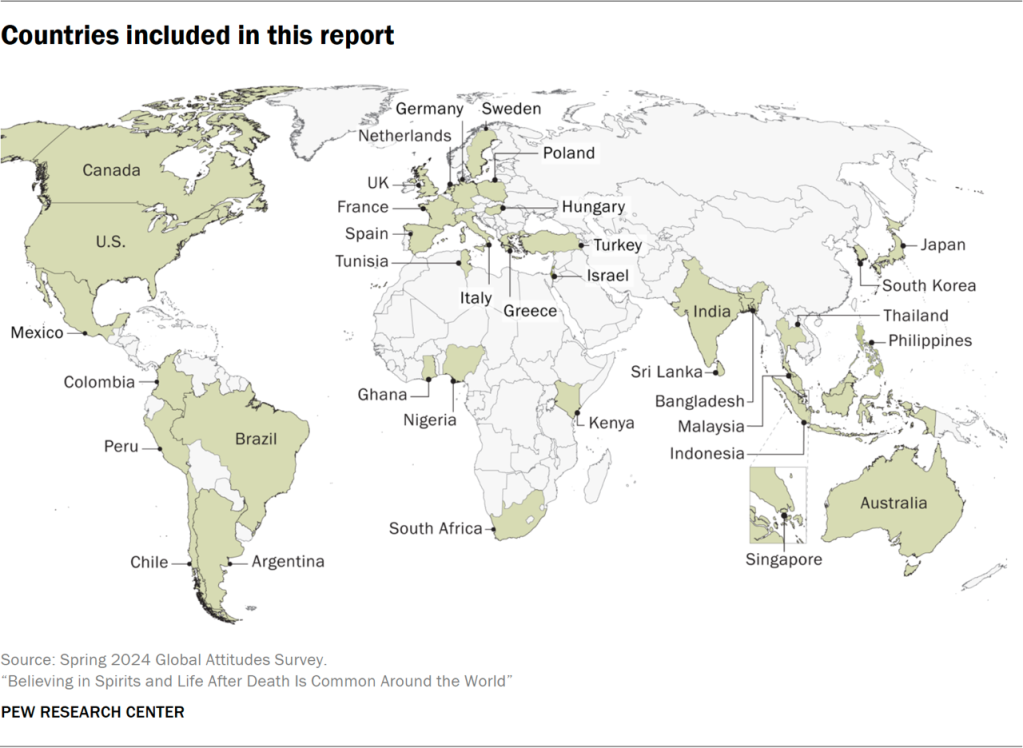

Over the last two decades, we’ve conducted surveys about religion and spirituality in more than 100 countries and territories. But in this survey, for the first time, we asked more than 50,000 people across six continents about some beliefs and practices that we previously had explored only in Asia or the United States.

This allows us to draw a fuller picture of spirituality around the world. Some of the concepts we asked about have roots in specific religious traditions – such as Judaism, Christianity and Islam, Hinduism and Buddhism, or Asian folk religions. Others are associated with less formal religious traditions that some people might label “New Age.”

We find that adults around the world – often across religious and geographic boundaries – share many of the beliefs and practices we asked about.

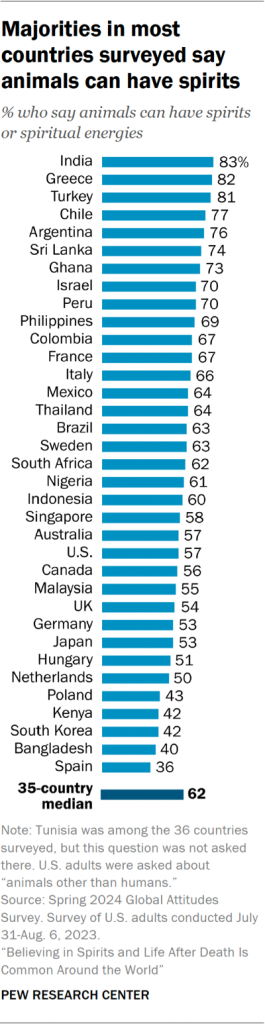

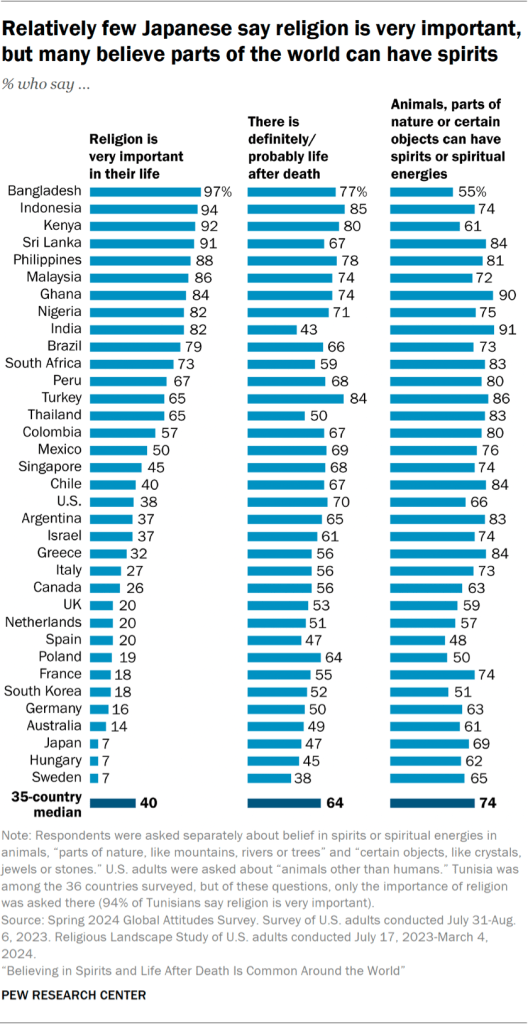

For example, majorities of adults in most countries surveyed say that animals can have spirits or spiritual energies. This includes 83% of adults in India, which has a Hindu majority. It also includes 81% in Muslim-majority Turkey, 76% in Christian-majority Argentina and 70% in Israel, the world’s only country with a Jewish majority.

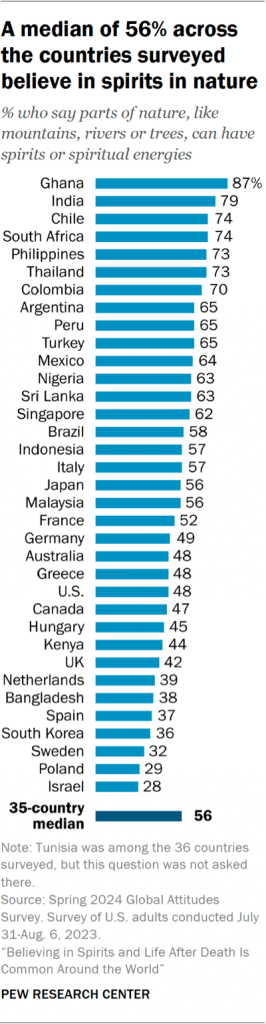

Many people around the world also believe that parts of nature (such as mountains, rivers or trees) can have spirits or spiritual energies. This belief is voiced by nearly three-quarters of adults in Christian-majority Chile (74%) and Buddhist-majority Thailand (73%), and by 57% in Muslim-majority Indonesia.

The U.S. falls somewhere in the middle of the countries surveyed on these questions: 57% of U.S. adults believe that animals can have spirits, while 48% say the same about mountains, rivers or trees. (Around six-in-ten U.S. adults identify as Christian, and about three-in-ten are religiously unaffiliated.)

In general, people around the world are much less likely to say that certain objects (such as crystals, jewels or stones) can have spiritual energies.

In some countries where large segments of the population do not identify with any religion, belief in spiritual forces nevertheless is fairly common. In Japan, for example, 53% of adults say that animals can have spirits, and 56% say that parts of nature can have spiritual energies – even though more than half of Japanese adults are religiously unaffiliated.

Related: Spirituality and Religion: How Does the U.S. Compare With Other Countries?

Age differences

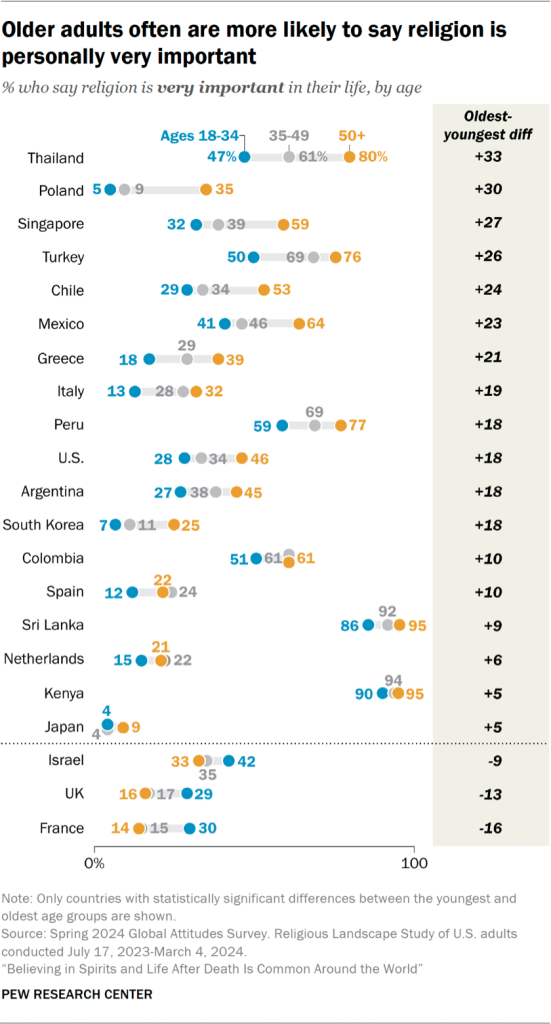

Previous Pew Research Center studies have shown that in many countries, older adults tend to be more religious than younger adults. This pattern has been observed around the world in traditional measures of religious identity and commitment, such as how many adults identify with a religion, attend religious services, consider religion to be very important in their lives and pray frequently.

But in addition to those standard questions, this survey includes a wider set of questions about spiritual topics, including beliefs about spirits and spiritual energies, life after death and the power of ancestral spirits. On some of these newer questions, we find much smaller differences between younger and older respondents.

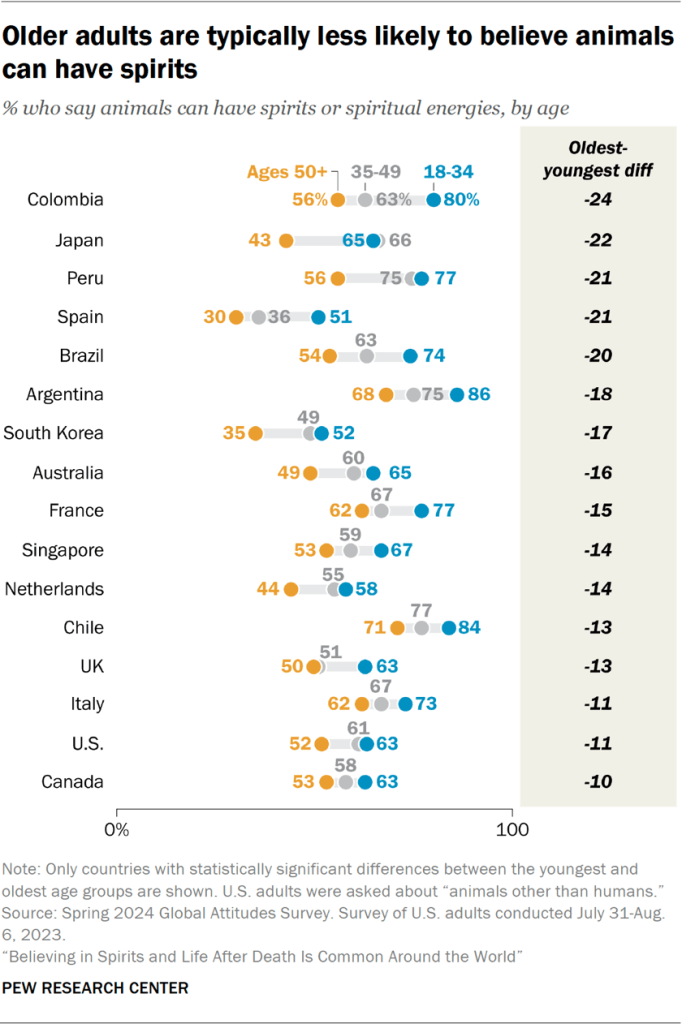

Indeed, on a couple of questions, the youngest adults (ages 18 to 34) seem to be more likely than the oldest adults (ages 50 and older) to believe in spiritual ideas.

For example, in about half of the countries surveyed, the belief that animals can have spirits is more common among the youngest adults than among the oldest age group. And in no countries are the oldest adults significantly more likely than the youngest adults to hold this belief.

Likewise, in 10 countries, the youngest adults are more likely than the oldest to say they believe in reincarnation, defined for survey respondents as the belief that “people will be reborn in this world again and again.” In most other countries, there are no significant age differences. Nigeria is the only place surveyed where the oldest adults are more likely than the youngest adults to believe in reincarnation (63% vs. 47%).

As in past surveys, we still find that older adults generally are more religious than younger adults when asked about topics like belief in God, attending religious services and the personal importance of religion.

For example, while eight-in-ten people ages 50 and older in Thailand say religion is very important in their lives, only about half of Thai adults under 35 say the same.

Life after death

In many previous surveys in the U.S. and some other parts of the world, we have posed questions about a specific vision of the afterlife, asking people whether they believe in heaven and, separately, whether they believe in hell. In this survey, to better allow comparisons across regions and religious traditions, we asked simply about “life after death.”

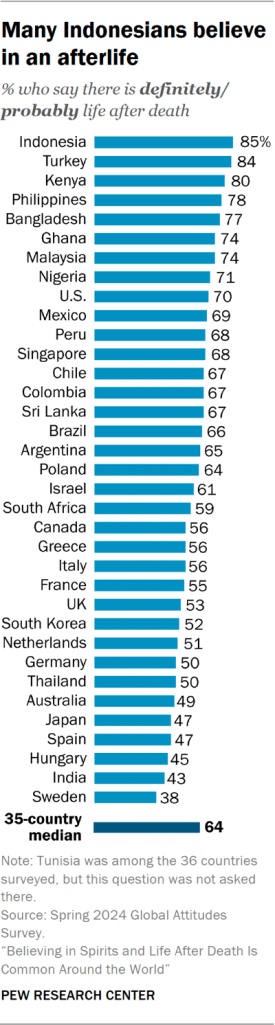

In most of the countries surveyed, a majority of adults say there is definitely or probably life after death. For example, 85% of adults in Muslim-majority Indonesia say this, as do 80% of adults in Christian-majority Kenya. And across the six Latin American countries surveyed, about two-thirds of adults believe there is an afterlife.

In a few countries, adults ages 18 to 34 are more likely than adults ages 50 and older to say there is an afterlife. But in the U.S. and Canada, the oldest adults are slightly more likely than the youngest adults to believe in life after death.

In the U.S., 70% of adults say there is definitely or probably life after death. (By comparison, 67% of Americans report believing in heaven, and 55% say they believe in hell, our 2023-24 U.S. Religious Landscape Study found.)

Comparing results across a spectrum of measures

In many of the countries surveyed, substantial shares of adults say religion is very important in their lives. This is especially true for countries in South and Southeast Asia, sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America, and less so for Western Europe. The U.S. is roughly in the middle of the pack, with 38% of Americans saying religion is very important in their lives.

Large percentages of people in most of the countries surveyed also express belief in life after death and say that animals, parts of nature (such as mountains, rivers or trees) or physical objects (such as crystals, jewels or stones) can have spirits.

While there is no clear and widely accepted dividing line between religion and spirituality, these questions show that even in countries where comparatively few people view religion as very important, many do hold beliefs in spirits and/or life after death.1

For example, relatively few Swedish adults (7%) say religion is very important to them. But more Swedes (38%) believe there is definitely or probably life after death, and nearly two-thirds believe in spirits in animals, parts of nature or objects.

On the other hand, India is among the countries where a high proportion of adults (82%) describe religion as very important in their lives. The vast majority (91%) also say that animals, parts of nature or objects can have spirits or spiritual energies. Indians (43%) are less likely than people in many of the other countries surveyed to believe in an afterlife, but about half of Indian adults (48%) believe in reincarnation.

Overall, the survey shows that some measures of religion and spirituality are strongly related to each other around the world. For example, people who say religion is very important in their lives often are more likely than others to fast during holy times, to pray daily, and to believe that spells, curses or other magic can influence people’s lives.

But the importance of religion is not strongly associated with some other measures, such as the belief that animals can have spiritual energies and the belief in reincarnation.

For more on how different measures of spirituality and religiousness relate to each other, read “How newer measures compare with long-standing measures of religiousness” later in this Overview.

These are among the key findings from surveys of more than 50,000 adults conducted by Pew Research Center in 36 countries. Surveys outside the U.S. were conducted from January through May 2024. Survey data for the U.S. comes from two waves of the Center’s American Trends Panel conducted in summer 2023 and February 2024, as well as from the most recent U.S. Religious Landscape Study (conducted July 2023 through March 2024). Globally, interviews were conducted in several dozen languages. For more information on how the data was collected in each country, read the Methodology.

The rest of this Overview covers:

- Economic connections to beliefs and practices

- Differences by religious group

- How newer measures compare with long-standing measures of religiousness

This report also includes:

- Chapter 1: God, spirits and the natural world

- Chapter 2: Beliefs about the afterlife

- Chapter 3: Spells, curses and ways to see the future

- Chapter 4: Spiritual and religious practices

- Chapter 5: Religious importance and religious affiliation

Economic connections to beliefs and practices

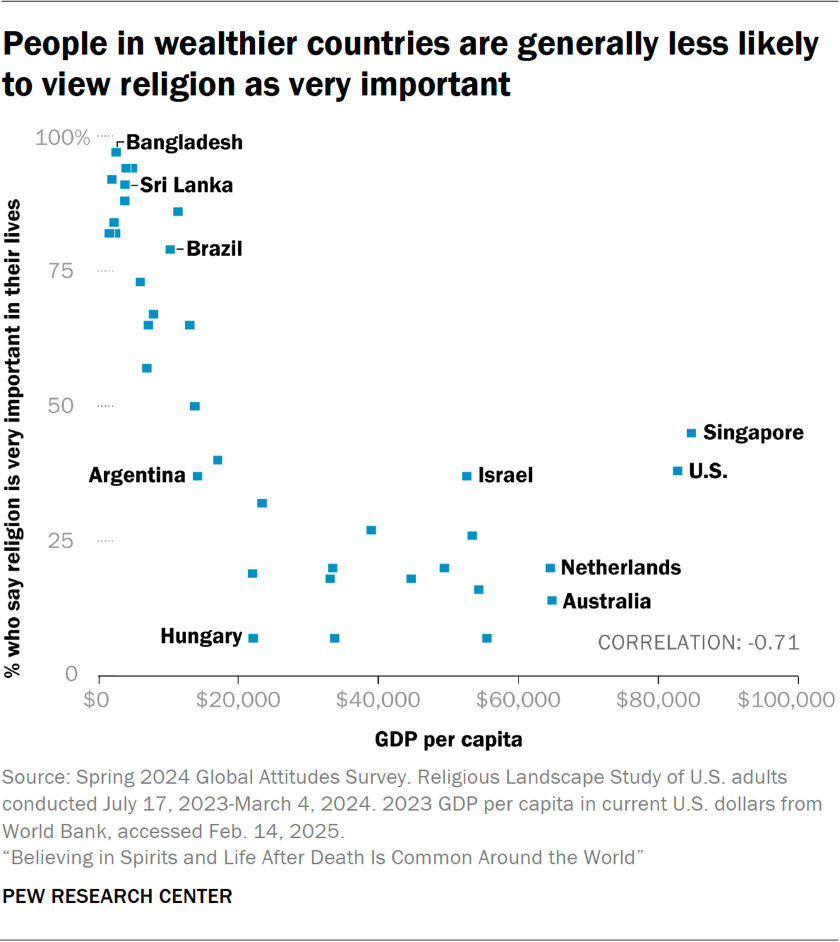

Scholars have long studied the relationship between economic development and religion, with “secularization theory” broadly positing that as societies become more economically and technologically advanced, religion and religious values become less important in people’s lives.

This theory continues to be debated, but international survey data has demonstrated a general pattern in which people in wealthier countries tend to pray less often and view belief in God as less important for morality, while people in less economically advanced countries tend to describe religion as more important in their lives.

This economic pattern continues to hold for traditional measures of religiousness (such as importance of religion, daily prayer and belief in God) in the three dozen countries analyzed in this report.

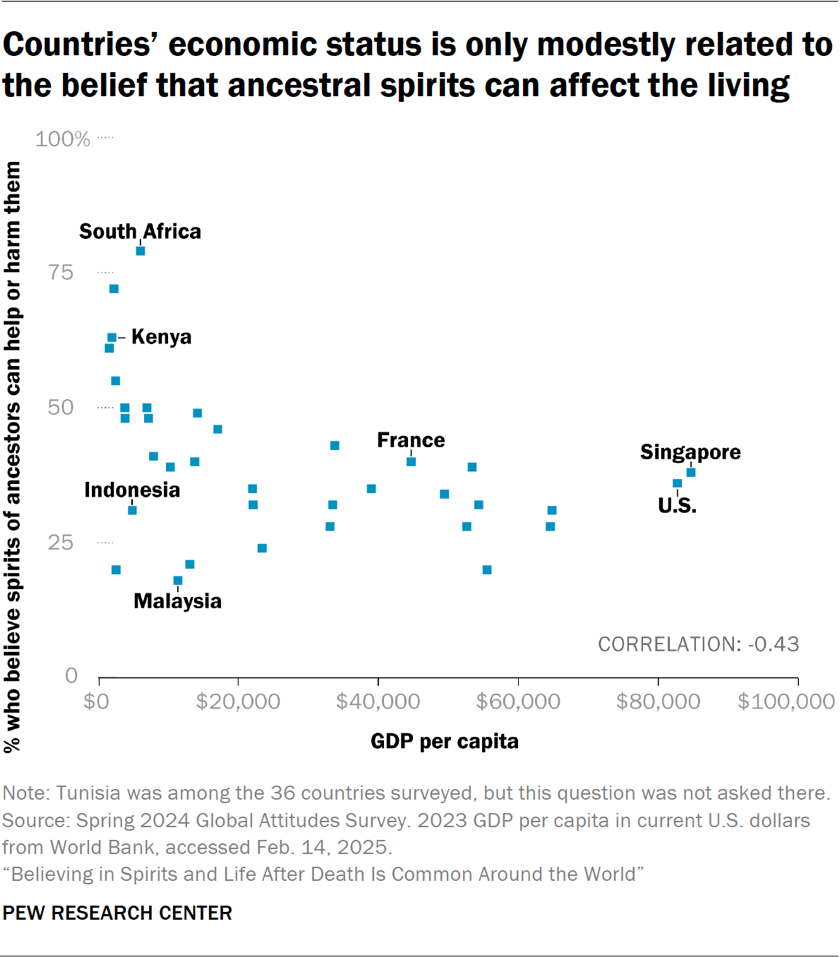

However, levels of national income are much less clearly correlated with some of the newer questions in the survey about religious and spiritual beliefs – such as belief in the power of ancestral spirits and the existence of “something spiritual beyond the natural world.”

Importance of religion

The share of people in each country who say religion is very important in their lives broadly follows what secularization theory would predict. Wealthier countries – those with higher per capita gross domestic product (GDP) – tend to have lower shares of adults who say religion is very important in their lives, with a fairly strong correlation.

In 11 countries, around eight-in-ten or more adults say religion is very important to them, and all these countries have relatively low GDPs per capita. They include Buddhist-, Christian-, Hindu- and Muslim-majority societies.

Conversely, in 11 countries, only two-in-ten adults or fewer say religion is very important in their lives, and all 11 are relatively wealthy countries (measured by GDP per capita). They include places with strong ties to Buddhism and Christianity, though most currently have large percentages of religiously unaffiliated adults.

Two high-income countries stand out on this measure. Singapore and the U.S. have the highest per capita GDPs of the countries surveyed, yet they fall in the middle on the question about religion’s personal importance, with 45% of Singaporeans and 38% of Americans saying religion is very important in their lives.

The correlation between economic advancement and religiousness also holds for several other measures, including religious service attendance; belief in God; and the belief that spells, curses or other magic can influence people’s lives. On these questions, wealthier countries tend to be the least religious, while less advanced economies are generally the most religious.

Belief that ancestors can affect the living

But the connection between economics and spirituality is not always so strong. For example, the correlation is much weaker on a question about whether ancestral spirits can help or harm the living.

Some of the less economically developed countries we surveyed have the highest shares of people who believe that the spirits of ancestors can intervene in our lives. Kenya (63%) and South Africa (79%) fall in that category.

Economics is not the only factor at play – the religious makeup of a country also has a role. For instance, the Muslim-majority countries of Bangladesh, Indonesia, Malaysia and Turkey also are among the less wealthy countries in our survey, yet people in those countries are among the least likely to say ancestors can interact with the living in these ways.

Something spiritual beyond the natural world

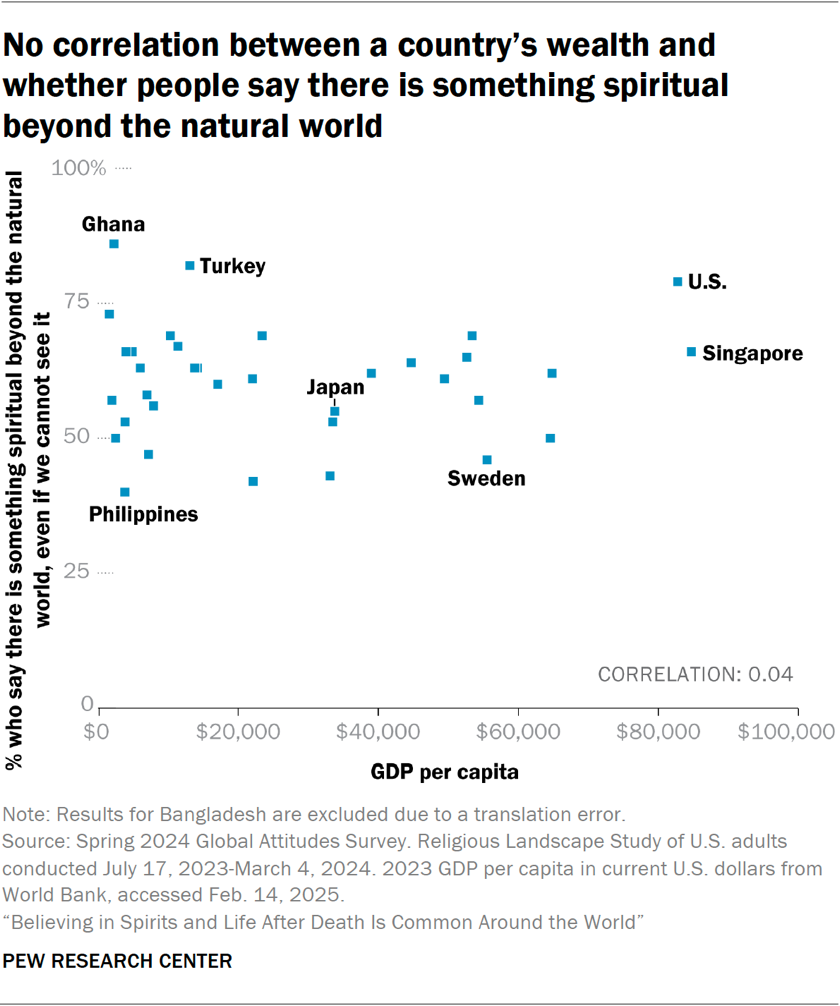

One measure of spirituality has basically no relationship with a country’s level of economic development: Living in a wealthier country is generally not correlated with either higher or lower shares of adults who say “there is something spiritual beyond the natural world, even if we cannot see it” rather than selecting the alternative response that “the natural world is all there is.”

The U.S. and Sweden, for instance, each have among the highest per capita GDPs in this survey. Yet a majority of U.S. adults (79%) say there is something spiritual beyond the natural world, while Swedish adults (46%) are among the least likely to say this.

Likewise, the countries with the lowest per capita GDPs represent a wide range of views on whether there is something spiritual beyond the natural world – from 86% in Ghana to 40% in the Philippines.

Differences by religious group

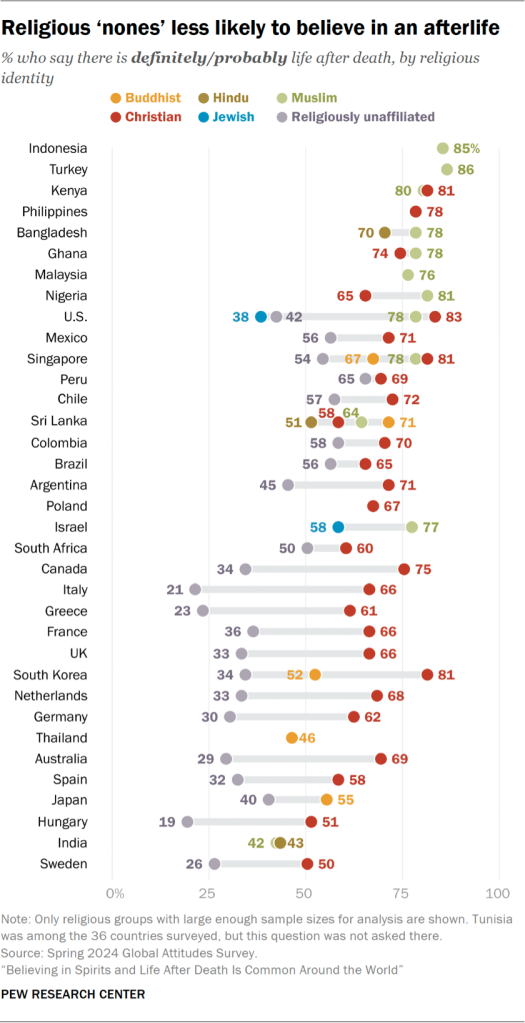

While levels of economic development seem to be connected to some aspects of spirituality and religion, we also see significant patterns based on religious identity. The nuances of these patterns vary depending on the specific measure. But in general, people who are religiously unaffiliated – i.e., those who describe themselves as atheist, agnostic or “nothing in particular” and are sometimes referred to as religious “nones” – tend to be less religious than people who affiliate with a religion within each country.

For example, in Germany, Christians are twice as likely as adults with no religion to say there is definitely or probably life after death (62% vs. 30%). And in nearly every country with enough Muslims to analyze separately, a majority of Muslims says there is life after death. Only in India do fewer than half of Muslims (42%) believe in an afterlife.

Meanwhile, Jewish adults in the U.S. and Israel (the only countries in the survey with sufficient samples of Jews to analyze) are much less likely than Muslims in the same two countries to believe in an afterlife.

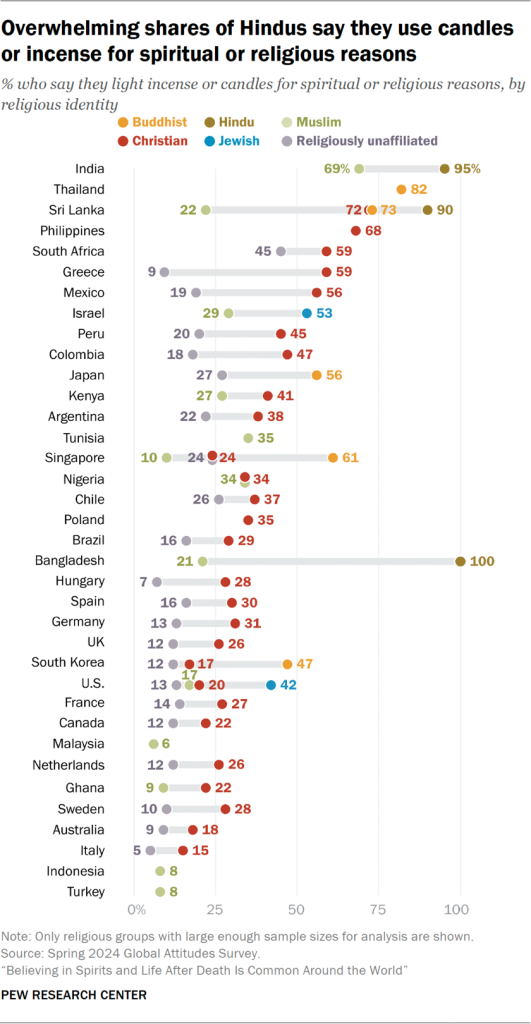

A different pattern emerges when comparing the shares of people who say they light incense or candles for spiritual or religious reasons. In Israel and the U.S., Jews are the most likely religious group to follow this practice. Muslims in both countries are much less likely to say they light candles or incense for religious or spiritual reasons.

Across the other 34 countries surveyed, though, Hindus and Buddhists tend to be the most likely to light incense or candles for spiritual or religious reasons. In India, for instance, nearly all Hindus follow this practice, while about two-thirds of Muslims do so.

And in countries with sufficient sample sizes to analyze Hindus and Buddhists separately, those two groups are consistently the most likely to say they believe in reincarnation – a mainstream teaching in both religions.

To read how people in different religious groups answered specific survey questions, go to the chapters on God and spirits, the afterlife, spells and ways to see the future, spiritual and religious practices, and the importance of religion in one’s life.

How newer measures compare with long-standing measures of religiousness

For decades, researchers have relied on some core measures of religious identity, beliefs and practices to assess the religiousness of individuals and societies, by asking questions such as:

- What is your current religion?

- How important is religion in your life?

- How often do you pray?

- How often do you attend religious services?

- Do you believe in God?

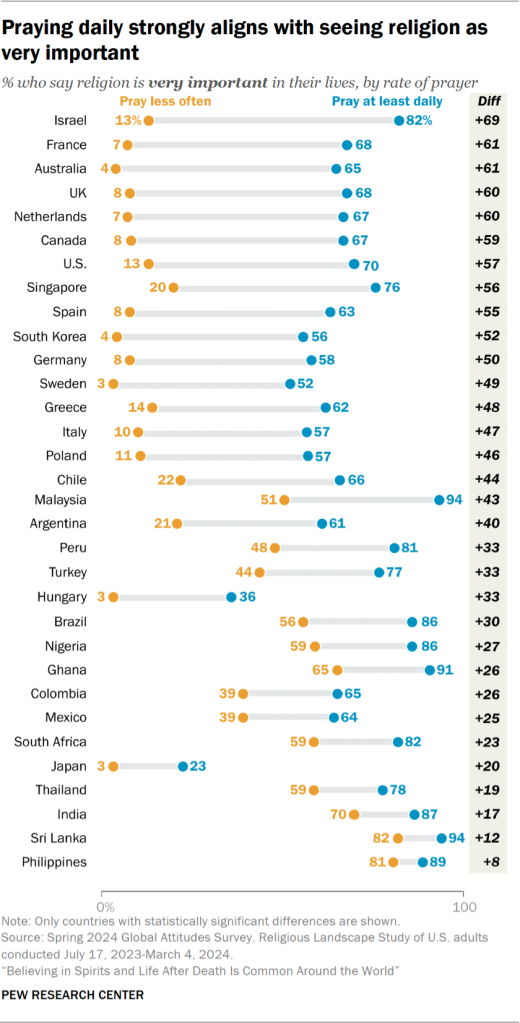

These measures are strongly associated with each other. In other words, if a person prays daily, that individual is significantly more likely than adults who pray less often to consider religion to be very important.

In Argentina, for example, 61% of adults who pray daily say that religion is very important in their lives, compared with 21% of Argentines who pray less often. Meanwhile, in Japan, 23% of those who pray daily say that religion is very important, while just 3% of Japanese adults who pray less often say religion is very important in their lives.

But what happens when we compare these long-standing measures of religiousness with the newer questions included in this survey?

The results depend on the measures used.

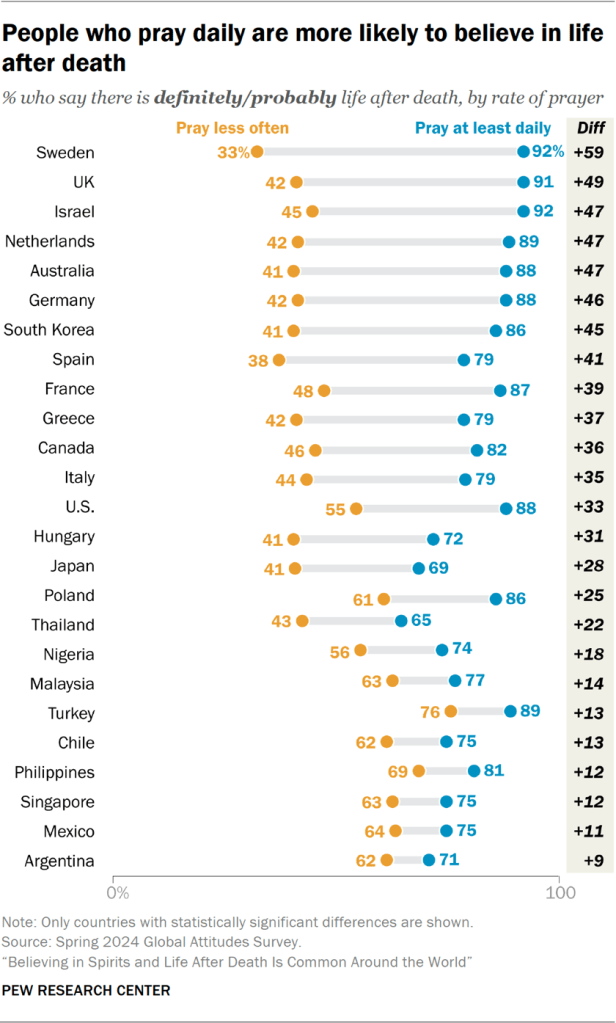

In general, there is a strong association between standard measures of religious commitment and whether people believe in life after death.

In Israel, for example, adults who pray daily are twice as likely as those who pray less often to believe there is life after death (92% vs. 45%).

But on some other measures, there is only a weak alignment – or even none at all.

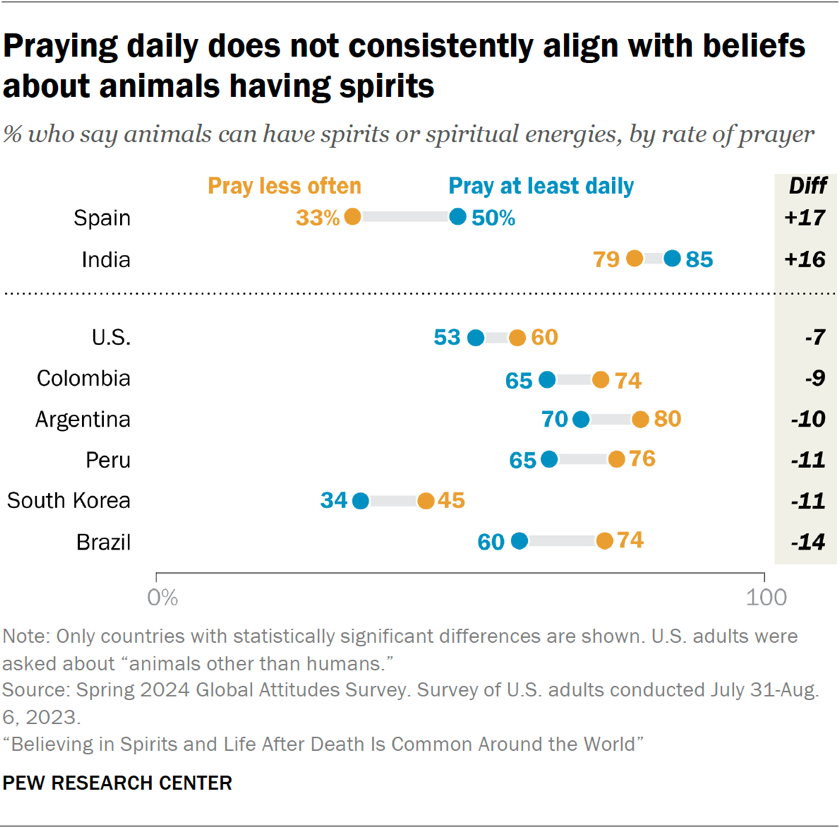

For instance, in most countries, adults who pray daily do not significantly differ from those who pray less often in their inclination to believe that animals have spirits, or in the likelihood that they consult a fortune teller or use other ways to see the future. This may reflect the fact that these beliefs and practices are less orthodox or central to the dominant faith traditions in many countries.

CORRECTION (May 14, 2025): A previous version of the chart “Praying daily does not consistently align with beliefs about animals having spirits” misstated the difference in responses to the question by rate of prayer in India. The chart has been replaced. This change does not substantively affect the findings of this report.