This is the 14th in a series of annual reports by Pew Research Center analyzing the extent to which governments and societies around the world impinge on religious beliefs and practices. The studies are part of the Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures project, which analyzes religious change and its impact on societies around the world.

To measure global restrictions on religion in 2021 – the most recent year for which data is available – the study rates 198 countries and territories by their levels of government restrictions on religion and social hostilities involving religion. The new study is based on the same 10-point indexes used in the previous studies.

- The Government Restrictions Index (GRI) measures government laws, policies and actions that restrict religious beliefs and practices. The GRI comprises 20 measures of restrictions, including efforts by governments to ban particular faiths, prohibit conversion, limit preaching or give preferential treatment to one or more religious groups.

- The Social Hostilities Index (SHI) measures acts of religious hostility by private individuals, organizations or groups in society. This includes religion-related armed conflict or terrorism, mob or sectarian violence, harassment over attire for religious reasons and other forms of religion-related intimidation or abuse. The SHI includes 13 measures of social hostilities.

To track these indicators of government restrictions and social hostilities, researchers combed through more than a dozen publicly available, widely-cited sources of information, including the U.S. Department of State’s annual Reports on International Religious Freedom and annual reports from the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF), as well as reports and databases from a variety of European and United Nations bodies and several independent, nongovernmental organizations. (Refer to the Methodology for more details on sources used in the study.)

For the latest data on government restrictions and social hostilities involving religion, read our report “Government Restrictions on Religion Stayed at Peak Levels Globally in 2022” and visit the interactive “Religious restrictions around the world.”

In 2021, government restrictions on religion – laws, policies and actions by state officials that limit religious beliefs and practices – reached a new peak globally, according to Pew Research Center’s latest analysis of government restrictions and social hostilities involving religion in 198 countries and territories around the world.

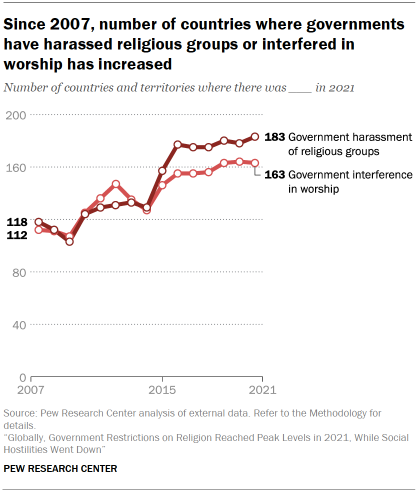

Harassment of religious groups and interference in worship were two of the most common forms of government restrictions worldwide in 2021.

Among the study’s key findings:

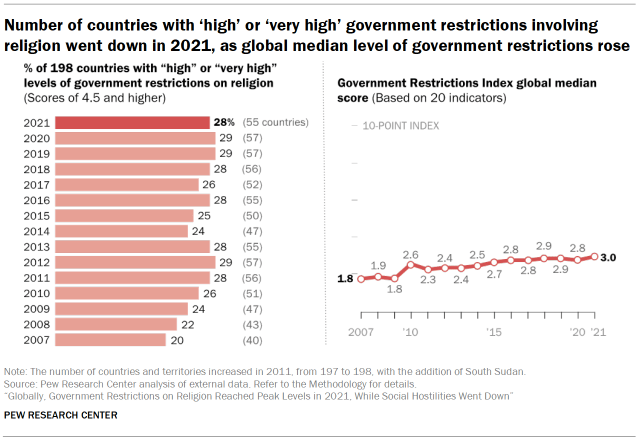

- The global median level of government restrictions on religion ticked up to 3.0 in 2021 from 2.8 in 2020 on the Government Restrictions Index, a 10-point scale of 20 indicators. This was the highest global median score since we began tracking restrictions in 2007.

- 55 countries (28% of the total) had “high” or “very high” levels of government restrictions in 2021, down slightly from 57 countries (29%), a level reached in 2020, 2019 and 2012. (The median index score for all countries rose anyway, partially because there were slightly more increases in index scores than decreases among the 198 countries and territories analyzed.)

- Religious groups faced harassment by governments in 183 countries in 2021, the largest number since the study began. Governments interfered in worship in 163 countries, down slightly from 164 in 2020 but still close to the all-time high.

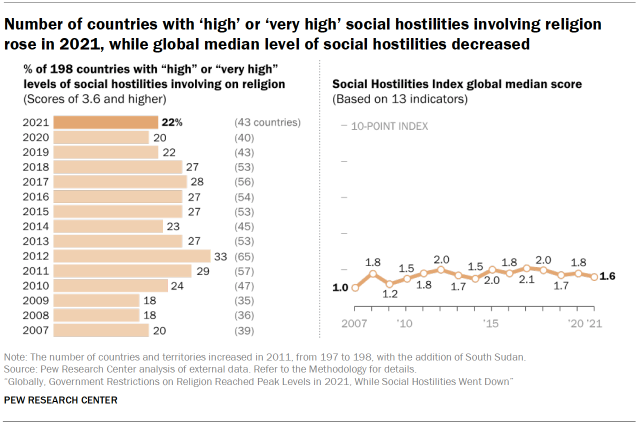

- The global median level of social hostilities involving religion – including violence and harassment by private individuals, organizations or groups – fell from 1.8 in 2020 to 1.6 in 2021 on the Social Hostilities Index, a 10-point scale composed of 13 indicators.

- 43 countries (22% of all studied) had “high” or “very high” levels of social hostilities in 2021, up from 40 countries (20%) in 2020 but still closer to the low point (18%) than to the high point (33%) previously recorded over the course of the study.

This report examines these and other findings from Pew Research Center’s 14th annual study of restrictions on religion around the world, including changes in the index scores at the global and regional levels. It also includes a section showing that governments in most countries simultaneously impose restrictions on religion and grant benefits to religious groups.

Some background on the study

Each year since 2007, Pew Research Center has tracked government restrictions and social hostilities on two 10-point indexes:

- The Government Restrictions Index (GRI): Government restrictions on religion include laws, policies and actions that regulate and limit religious beliefs and practices. They also include policies that single out certain religious groups or ban certain practices; the granting of benefits to some religious groups but not others; and bureaucratic rules that require religious groups to register to receive benefits.

- The Social Hostilities Index (SHI): Social hostilities include actions by private individuals or groups that target religious groups; they also include actions by groups or individuals who use religion to restrict others. The SHI captures events such as religion-related harassment, mob violence, terrorism/militant activity, and hostilities over religious conversions or the wearing of religious symbols and clothing.

Government restrictions have increased gradually over time since 2007, when the global median level on the GRI was 1.8.

Social hostilities – which capture incidents that are more likely to vary from year to year – have seen more fluctuations. On the SHI, the global median score started at 1.0 in 2007, reached a peak of 2.1 in 2017, and fell to 1.6 in 2021.

Countries with ‘high’ and ‘very high’ government restrictions and social hostilities in 2021

Another way to examine restrictions and hostilities involving religion is to look at the number of countries in the “high” or “very high” categories on each index.

In 2021, 28% of countries had “high” or “very high” levels of government restrictions, a slight decline from 29% in 2020.

Meanwhile, fewer countries (22%) had “high” or “very high” levels of social hostilities.

The majority of countries in the study had “moderate” or “low” levels of government restrictions and social hostilities.

Government harassment of religious groups, interference in worship in 2021

Two measures – government harassment of religious groups and government interference in worship – have contributed to the GRI scores in most of the countries analyzed.

Government harassment can include a wide range of actions or offenses, from the use of physical force targeting religious groups to derogatory comments by government officials. It can also include laws and policies that single out groups or make religious practice more difficult.

In 2021, governments harassed religious groups in 183 countries (92% of countries analyzed), up from 178 countries in 2020. This type of restriction was widespread across all five regions we analyzed. For example, at least one case of government harassment was reported in each of the 20 countries in the Middle East-North Africa region. The same was true for 43 of 45 countries in Europe (96%), 33 of 35 countries in the Americas (94%), 44 of 48 countries in sub-Saharan Africa (92%) and 43 of 50 countries in the Asia-Pacific region (86%).

In Europe, for example, Geert Wilders, who leads the Party for Freedom in the Netherlands (a party that held seats in government in 2021 and went on to win more seats in 2023), called for the “de-Islamization” of the country on Twitter (now known as X). He also proposed “a series of measures including closing all mosques and Islamic schools, banning the Quran, and barring all asylum seekers and immigrants from Muslim-majority countries,” according to the U.S. State Department. (Statements targeting religious minorities and asylum seekers are not new in either the country or in the region and were detailed in our report looking at restrictions in 2016.)

In the Americas, the government of Nicaragua has targeted Catholic clergy for supporting the country’s pro-democracy movement, according to the U.S. State Department. The president and the vice president (who is also the first lady) called priests and bishops “terrorists in cassocks” and “coup-plotters.” Meanwhile, a member of the National Assembly, Wilfredo Navarro Moreira, called a cardinal and several bishops “servants of the devil” in a television interview.

Other government harassment activities measured on the GRI include policies that make religious practices more difficult – such as restrictions on religious dress, which tend to affect Muslim women, and laws limiting halal or kosher meat production, which generally affect Muslims and Jews.

In several European countries, for example, authorities in recent years have imposed bans on headscarves or full-face veils that tend to affect Muslim women, even as exceptions are sometimes made for people who wear them for nonreligious reasons.

Austria, for example, forbids full-face coverings unless they are worn for “artistic, cultural, or traditional events, in sports, or for health or professional reasons.” Face coverings such as women’s burqas and niqabs are also banned in Denmark.

In addition, Denmark does not allow the slaughter of animals for meat unless the animals are stunned before being killed, a restriction that makes it harder for Jews and Muslims to follow their religions’ dietary guidelines. (Kosher and halal meat can be imported from other European Union countries, but Jews and Muslims have expressed frustration about the law.)

Governments interfered in worship in 163 countries (82% of countries in the study) in 2021, down from a peak of 164 in 2020. Our definition of government interference in worship includes laws, policies and actions that disrupt religious activities, the withholding of permits for such activities, or denying access to places of worship. This measure also includes restrictions on practices and rituals that may not be specifically tied to worship, such as burial practices and conscientious objection to military service for religious reasons.1

As with government harassment, there was at least one report of government interference in worship in every country in the Middle East-North Africa region, along with 91% of countries in Europe, 81% in sub-Saharan Africa, 80% in the Americas and 70% in Asia and the Pacific.

For example, in the Maldives, where Islam is the state religion, non-Muslim groups are forbidden to build places of worship or practice their faith publicly. Similarly, Egyptian law allows only members of recognized religious groups (Sunni Islam, Christianity and Judaism) to express their faith in public and construct houses of worship.

In 2021, cases of government interference in worship also included the use of force against religious leaders who violated COVID-19 restrictions. In some countries, religious groups claimed (as they had in 2020) that public health measures were unevenly or unfairly applied to their activities and places of worship, particularly in comparison with businesses like shops and restaurants.

In Canada, three churches that were fined for defying lockdown measures in British Columbia filed a legal challenge in 2021 against public health orders that limited religious gatherings, according to the U.S. State Department. The churches contended that there were fewer restrictions on restaurants and other businesses, as well as on Orthodox Jewish synagogues that were allowed to hold indoor services. In addition, several Canadian clergy were fined and arrested after holding in-person services that violated public health measures.

Government restrictions and government benefits

This section analyzes how many countries have governments that provide benefits to religious groups and, at the same time, harass religious groups and interfere in worship.

Here’s what we found in 2021:

- In 127 countries, governments provided funds or other resources for religious education.

- In 107 countries, governments gave funds or other resources for religious buildings, such as for construction, upkeep or maintenance of houses of worship.

- In 67 countries, governments provided benefits to clergy, such as salaries, exemptions from military service, or access to certain government jobs (such as military or prison chaplaincies).2

Overall, governments in 161 countries provided at least one of these benefits to religious organizations. Yet, at the same time, governments in most of these countries also harassed religious groups (149 countries) and/or interfered in worship (134 countries).

Our data did not allow us to discern why countries grant benefits to religious groups, for example, whether governments hope that paying the salaries of clergy will lead those clergy to deliver sermons that align with government views. So we cannot say whether specific governments are attempting to manipulate, entice or co-opt religious groups with incentives.

Still, the analysis adds a layer of complexity to the relationship between governments and religious groups. For example, it shows that some governments that provide benefits to clergy also, at the same time, seek to restrict and control these clergy – for example by directly restricting what they can say in sermons.

Funds for religious education

In 2021, governments in 127 countries gave money to religious education initiatives in their countries. This included payments for teachers’ salaries at religious schools or subsidies for the schools more broadly.

In Trinidad and Tobago, for example, the government gave money to “religiously affiliated public schools” run by Christians, Hindus and Muslims. The government also provided most construction costs for these schools.

In the Netherlands, the government funded religious schools and “other religious educational institutions” if they satisfied certain education requirements and complied with guidelines regarding class sizes. And in Sweden, the government helped fund independent religious schools through a voucher system; the schools had to abide by national curriculum guidelines.

In Singapore, even though the country does not generally allow religious education in public schools, there were 57 “government-subsidized religiously affiliated schools” in 2021. According to the sources used in this study, most of these schools were Christian; three were Buddhist.

Funds and tax exemptions for religious property

In 107 countries, governments gave property-related benefits to religious groups in 2021, often through direct subsidies or tax exemptions.

In Malaysia, a federal entity devoted to Islamic affairs provided funds for mosque projects. While no funds were specifically allocated for non-Muslim groups, temples and churches also received funding, according to the U.S. State Department’s International Religious Freedom Report. And from December 2020 to May 2021, 1,145 Hindu temples received Malaysian government funding.

In Germany, state governments provided funds to renovate and build synagogues. In the state of Baden-Wuerttemberg, the local government also signed a contract in 2021 with Jewish communities to provide funds for security for synagogues and for the establishment of a Jewish academy.

In Angola, registered religious groups did not have to pay some property taxes. And in Gabon, registered religious groups were exempt from fees for land-use and construction permits.

In some cases, governments provided resources to historically significant religious sites. For example, the Egyptian government, “in a potential boost to religious tourism,” worked to restore many historic sites important to Christians, Jews and Shiite Muslims.

Government benefits to clergy

In addition, our analysis showed that 67 countries gave government benefits specifically to clergy – including payments of salaries, exemption from military service, and access to certain government positions like military and prison chaplaincies – in 2021.

The most common type of benefit to clergy in 2021 was payment of salaries (found in 42 of the 67 countries). In Jordan, for example, a government agency called the Ministry of Awqaf (religious endowments), managed mosques in the country and provided salaries for their staffs. In Algeria, the government provided salaries and benefits for religious personnel of mosques and churches. And in Iceland, in 2021, the Evangelical Lutheran Church received government funds to pay for its staff’s salaries and benefits.

Sometimes clergy receive legal benefits from the government. In Honduras, for instance, high-ranking clergy in many religious groups are exempt from court subpoenas. And in Canada, clergy who are part of religious groups with nonprofit status receive benefits such as a “housing deduction” and “expedited processing through the immigration system.”

In 36 countries, only clergy who are associated with a religion that is favored or preferred by the government – either through official status or various types of preferential treatment – received these types of benefits in 2021.

In Peru, for example, the constitution recognizes the Catholic Church as having an important role in the country, while a concordat with the Vatican allows the Church “certain institutional privileges in education, taxation, and immigration of religious workers.” The military hires only Catholic chaplains, Catholicism is taught in religion classes at public schools, and Catholic bishops must approve the teachers who teach these classes.

Restrictions in these countries

In most of the countries that provide benefits to religious groups or clergy, the government also harassed some religious groups or interfered in worship in 2021.

For instance, in Sunni-majority Saudi Arabia, where the government funds the construction of most Sunni mosques and gives a monthly stipend to imams at the mosques, sermons are restricted by the Ministry of Islamic Affairs, which directs the imams to choose from an approved list. The content is not permitted to be “sectarian, political or extremist, promoting hatred or racism, or including commentary on foreign policy,” according to the U.S. State Department. Ministry officials have authority to attend sermons to ensure imams don’t preach about forbidden topics.

The Saudi government also has targeted Sunni clerics (along with Shiite clerics) when they express religious views deemed unacceptable by the government. One Sunni cleric, Hassan Farhan al-Maliki, remained in prison without due process for “allegedly calling into question the fundamentals of Islam,” according to the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom. He was charged with 14 crimes and has been in prison since 2017.

A similar situation exists in Jordan, where the government both pays the salaries of mosque employees across the country and forces imams to stick to selected themes for their Friday sermons. Imams who do not follow these guidelines can be fined, suspended, imprisoned or forbidden from giving Friday sermons.

In Ethiopia, where the government funded 219 Islamic schools and 250 Catholic schools in 2021, government security forces used tear gas against crowds of thousands of Muslims who had gathered in Addis Ababa for a Grand Iftar event during the Islamic holy month of Ramadan.

In Austria, where buildings used by recognized groups for religious purposes are exempt from property taxes, a new anti-terrorism law allows officials to more easily shut down mosques to “protect public security.”

Pew Research Center has conducted other analyses of relationships between governments and religious groups, outside the scope of the annual restrictions reports. For example, in 2017 we published a report on countries with official state religions, and in 2019, we examined the tradition of “church taxes” in Western Europe.

Jump to the following chapters to read more on …

- Changes in the Government Restrictions Index and the Social Hostilities Index (Chapter 1)

- Physical harassment of religious groups around the world (Chapter 2)

- Religion-related government restrictions and social hostilities by geographic region (Chapter 3)

- Restrictions in the world’s 25 most populous countries (Chapter 4)