Historically, in Indian society, sons have been expected to take care of their aging parents, and men have been the main beneficiaries of inheritance. Meanwhile, married women often live with and support their in-laws. In line with these and other traditions, families have tended to place higher value on – and provide more support to – their sonsthan their daughters, a set of attitudes and practices known as “son preference.”

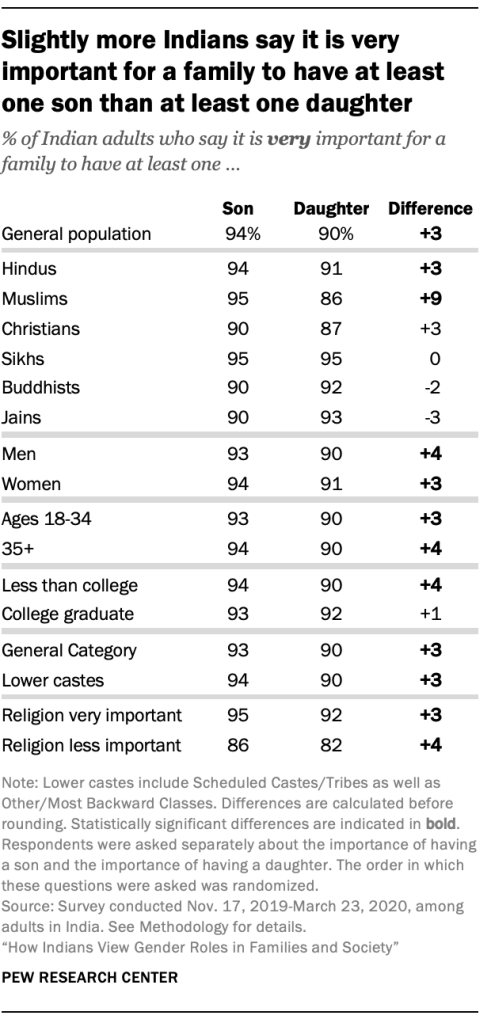

Today, nearly all Indian adults say it is either very important or somewhat important for a family to have at least one son, but an identical share (99%) also separately say it is important to have a daughter. Indians are only slightly more likely to say that it is very important to have a son than to have a daughter (94% vs. 90%).

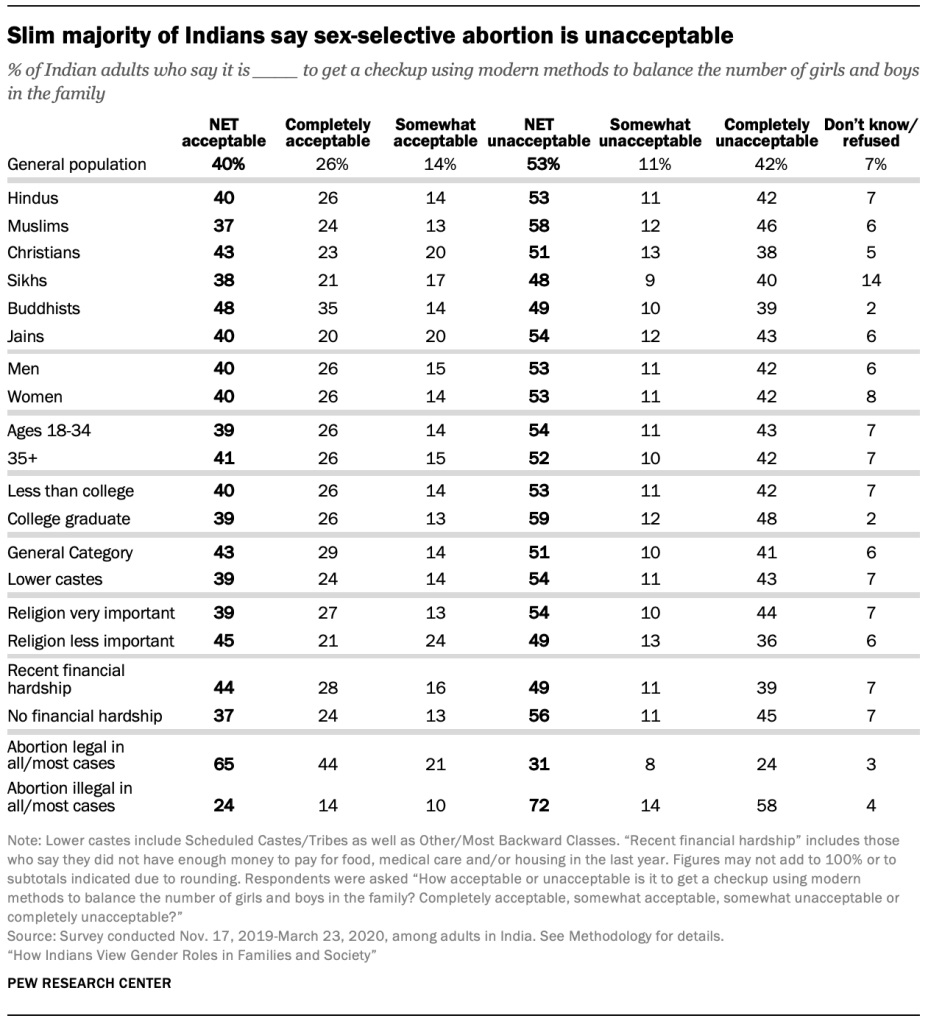

However, one enduring manifestation of son preference has been the practice of sex-selective abortions – using ultrasound or other tests to learn the sex of a fetus and terminating the pregnancy if the fetus is female. While the Indian government has enacted measures meant to curtail this practice, the survey finds that a substantial minority of Indians (40%) say it is completely acceptable or somewhat acceptable “to get a checkup using modern methods to balance the number of girls and boys in the family.” On the other hand, roughly half of adults (53%) – including most Muslims (58%), Jains (54%) and Hindus (53%) – say that this practice is either “somewhat unacceptable” or “completely unacceptable.” (The indirect phrasing of the question, while perhaps unfamiliar to people outside of India, was carefully tested by survey researchers in India in order to convey the concept of sex-selective abortion to respondents without being offensive.)

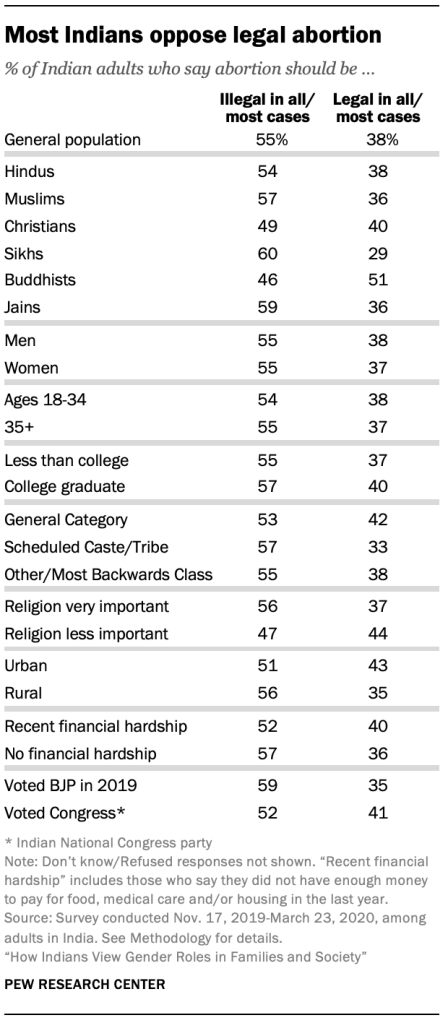

A majority of Indian adults (55%) also say that abortion in general should be illegal in all or most cases, even though the medical procedure was legalized in the 1970s and continues to be legally available in India today. Indians’ views on abortion are correlated with their views on sex-selective abortion: Those who oppose abortion overall are more likely to see sex-selective abortion as unacceptable.

Nearly all Indians say it is important for a family to have both a son and a daughter

Indians nearly universally say it is at least somewhat important for families to have at least one son (99%) and, separately, at least one daughter (99%). This includes at least nine-in-ten who say it is very important to have a son (94%) and a daughter (90%).

Muslims are somewhat more likely to say it is very important to have a son than a daughter (95% vs. 86%, respectively). This gap is smaller for Hindus (94% vs. 91%) and nonexistent for Sikhs (95% each).

Adults who say religion is very important in their lives are more likely than others to say it is very important to have both sons and daughters. For instance, 95% of Indians who say religion is very important in their lives think it is very important to have at least one son, compared with 86% of Indians who place less importance on religion. Indians who say religion is very important also are somewhat more likely than others to have any children, regardless of gender (76% vs. 69%).

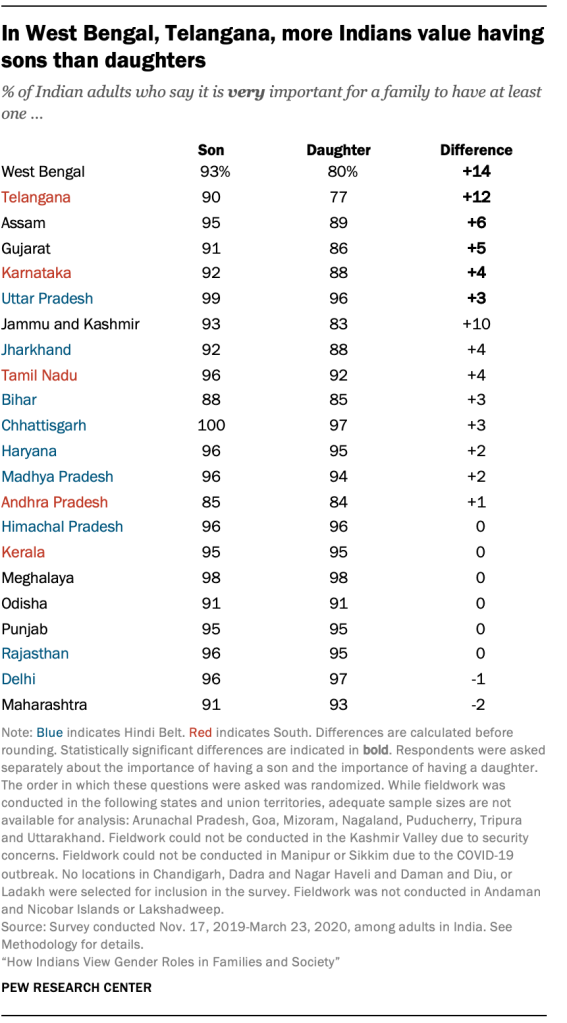

Residents in some states are significantly more likely to place importance on having a son than a daughter. These states are scattered across India. For example, in both the Eastern state of West Bengal and in the Southern state of Telangana, noticeably larger shares say it is very important for a family to have a son (93% and 90%, respectively) than to have a daughter (80% and 77%).

Four-in-ten Indians say it is acceptable ‘to balance the number of boys and girls in a family’

Son preference in India has affected both individual families and society at large. Indeed, India’s sex ratio at birth has long been skewed, with significantly more boys than girls born each year than would be expected under natural conditions. This imbalance increased along with the rise of ultrasound technology, which made it easier for some Indians to selectively abort female fetuses; in other cases, female babies have been killed after birth.

Over time, the Indian government has taken different approaches to try to prevent sex-selective abortions, such as the Pre-Conception and Pre-Natal Diagnostic Techniques Act of 1994 (amended in 2003), which banned testing for the sex of the fetus. According to the 2011 census, there were 111 boys born for every 100 girls born in India, but recent data suggests the gap may be narrowing.10

Given the sensitivity around this topic – and the fact that it is illegal in India for medical providers to tell parents the sex of a fetus – the survey could not directly ask respondents if they thought sex-selective abortion should be legal or illegal. Instead, a euphemism was used. The survey asked Indians how acceptable or unacceptable it is to “get a checkup using modern methods to balance the number of girls and boys in a family.”

Fully 40% of Indian adults say this practice is at least “somewhat” acceptable, including roughly a quarter (26%) who say it is completely acceptable. Meanwhile, about half of adults say sex-selective abortion is somewhat unacceptable (11%) or completely unacceptable (42%). Men and women have virtually identical views on this topic, and differences by religion on this question are generally modest.

Adults who say abortion in general should be legal in all or most cases (see “Most Indians say abortion should not be legal”) are substantially more likely than other Indians to say that sex-selective abortion is at least somewhat acceptable. Moreover, Indians who have had difficulty purchasing food, medicine or housing for their family in the past year are more likely than those who did not have these financial difficulties to say the practice can be acceptable. At the same time, adults from General Category castes are slightly more inclined than those from lower castes to see sex-selective abortion as acceptable (43% vs. 39%).

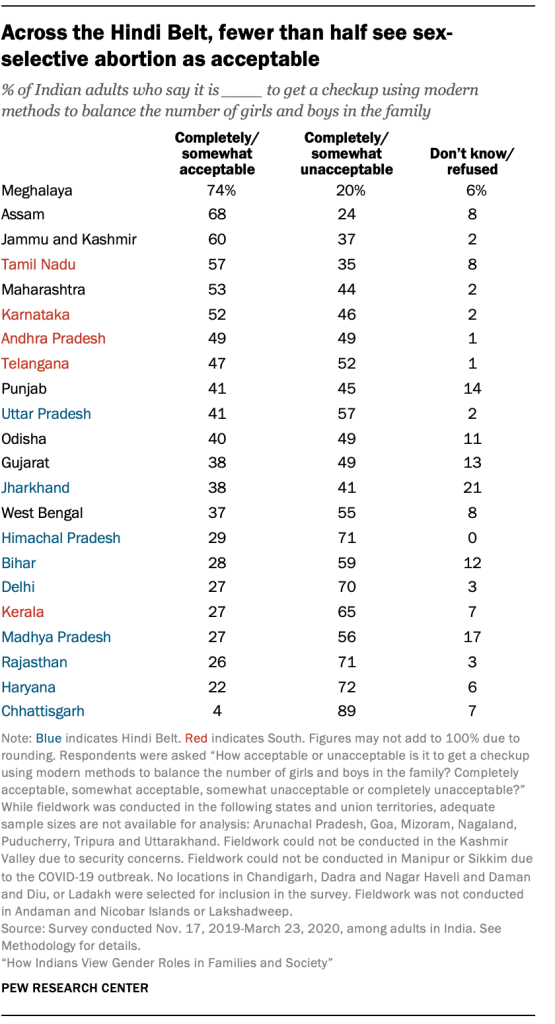

Looking at this question at the state level, at least one-in-five people in nearly every state say sex-selective abortion is acceptable. Chhattisgarh stands out as an exception; just 4% of Indians there say the practice is somewhat or completely acceptable. Meanwhile, a few states – including Meghalaya (74%), Assam (68%) and Tamil Nadu (57%) – have clear majorities who say sex-selective abortion is at least somewhat acceptable.

In some states, a relatively high proportion of survey respondents say they do not know or decline to answer the question, including roughly one-in-five in Jharkhand (21%) and 17% in Madhya Pradesh.

In several states in the country’s Hindi Belt, relatively few people say the practice of sex-selective abortion is acceptable, while majorities consider it unacceptable. Despite these opinions, some of these states, such as Haryana, have had highly skewed gender ratios, suggesting the widespread prevalence of sex-selective abortion in the region. For example, the 2011 census found a ratio of 121 boys born per 100 girls born in Haryana.11

More recently, however, there is some evidence that the sex ratios in these states have become more balanced. In the 2019-2021 National Family Health Survey (NFHS), data showed that Haryana’s sex ratio at birth had become less skewed, at 112 boys to 100 girls. In neighboring Punjab – which is not part of the Hindi Belt but has also had a highly skewed sex ratio – the most recent NFHS survey once again showed considerable change: In the 2011 census, there were 119 boys for every 100 girls born in the state, but in 2019-2021, Punjab’s sex ratio at birth was somewhat closer to normal, at 111 boys per 100 girls. These trends suggest that the practice of sex-selective abortion may be in decline, perhaps as a result of laws banning the practice and greater awareness generated by public education campaigns. Data from India’s next census (scheduled to be conducted in 2022) is expected to provide a more definitive picture.

Most Indians say abortion should not be legal

In 1971, India legalized abortion for women through the first 12 weeks of pregnancy – and, in some circumstances, up to 20 weeks. Since then, legal abortion access has expanded several times, most recently in a 2021 law allowing abortions in some cases through 24 weeks of pregnancy.12

Despite this, the survey finds that most Indian adults do not believe abortion should generally be legal. Indeed, a slim majority (55%) say abortion should be illegal in all or most cases, including 36% who say it should be illegal in allcases. Just 38% of Indians say it should be legal in all or most cases.

At least half of adults surveyed in most of India’s major religious groups say abortion should be illegal in all or most cases. However, Buddhists are more likely than members of other religious communities to say abortion should be legal in all or most cases (51%), including 36% who say it should be legal in all cases.

Adults who say religion is very important in their lives are more likely than those for whom religion is less important to say abortion should be illegal (56% vs. 47%). Additionally, nearly six-in-ten Indians who say they voted for the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) in the 2019 national election (59%) say abortion should be illegal, while roughly half of Indians who voted for the opposition Indian National Congress party say the same (52%).

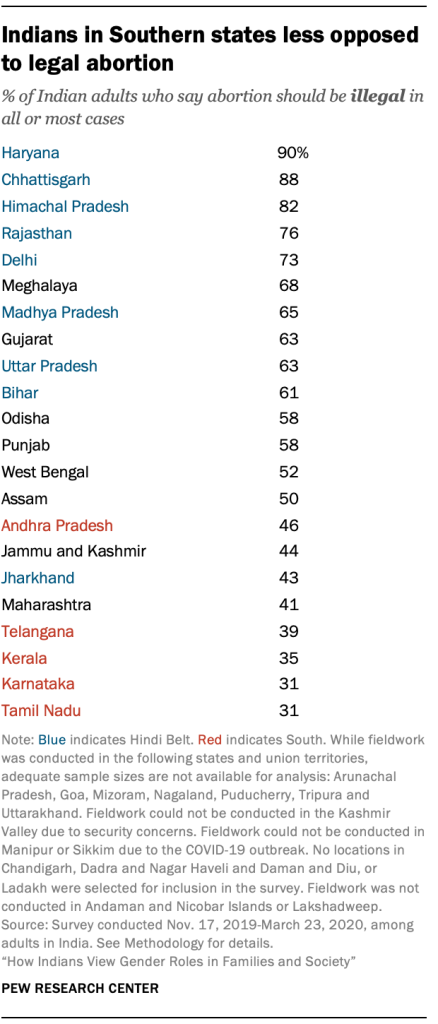

In most Indian states, half of adults or more say abortion generally should be illegal, but Indians who live in the South of the country are less likely to take this view. For example, fewer than half of respondents say abortion should be illegal in all or most cases in Andhra Pradesh (46%), Telangana (39%), Kerala (35%), Karnataka (31%) and Tamil Nadu (31%).

Overall, opposition to abortion is higher among Indians who live in Hindi Belt states, like Haryana (90%) and Rajasthan (76%), than in other parts of the country.

However, significant differences sometimes exist between neighboring states. For example, a majority of Indians in the Hindi Belt state of Bihar say abortion should be illegal in all or most cases (61%), compared with roughly four-in-ten in bordering Jharkhand (43%).