Religion in public schools has long been a controversial issue. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1962 that teachers and administrators cannot lead prayers in public schools, and a decision in 2000 barred school districts from sponsoring student-led prayers at football games. At the same time, the court has held that students retain a First Amendment right to the free exercise of religion and may voluntarily pray before, during and after school. Where exactly to draw the line between constitutionally protected religious activity and impermissible state-sponsored religious indoctrination remains under dispute. This year, the Supreme Court declined to hear a case involving a high school coach who was fired for leading prayer after games, just one of several recent controversies in this area of law.

While periodic battles continue in the courts, what is the day-to-day experience of students in public schools across the country? A new Pew Research Center survey asked a nationally representative sample of more than 1,800 teenagers (ages 13 to 17) about the kinds of religious activity they engage in – or see other students engaging in – during the course of the school day.

The survey finds that about four-in-ten teens who attend public schools say they commonly (either “often” or “sometimes”) see other students praying before sporting events at school. This includes about half of teenage public schoolers who live in the South, where students are more likely than those in other regions to witness and partake in various religious expressions at school.

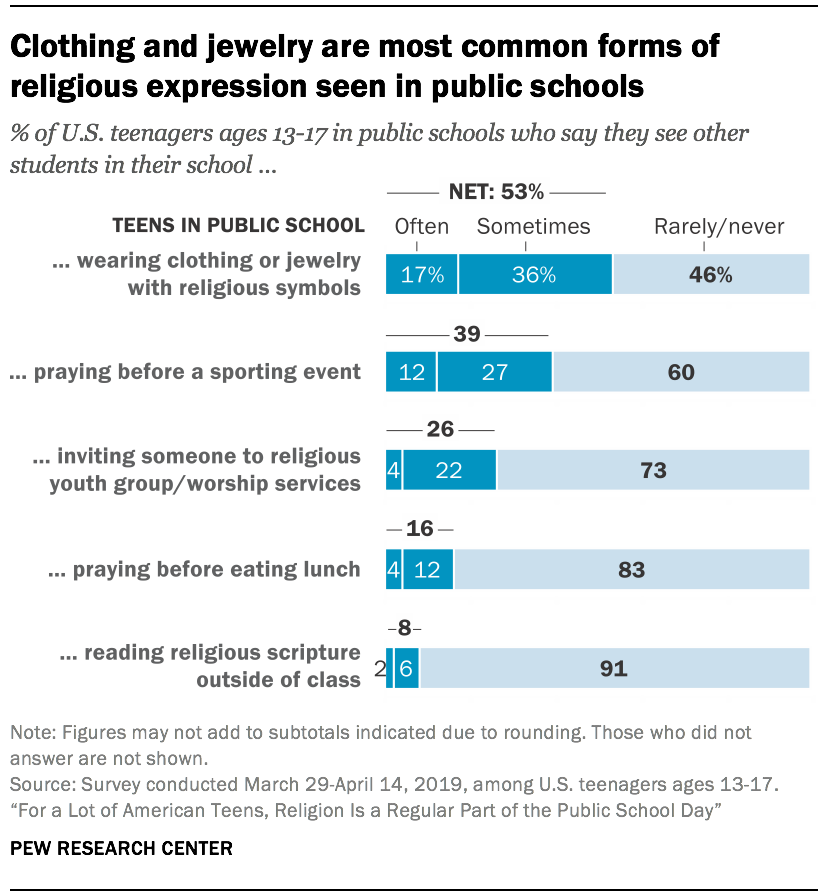

In addition, roughly half of U.S. teens who attend public school say they commonly see other students in their school wearing religious clothing (such as an Islamic headscarf) or jewelry with religious symbols (such as a necklace with a Christian cross or a Jewish Star of David).

About a quarter of teens who attend public schools say they often or sometimes see students invite other students to religious youth groups or worship services. About one-in-six (16%) often or sometimes see other students praying before lunch in their public school. And 8% report that they commonly see other teenagers reading religious scripture outside of class during the school day.

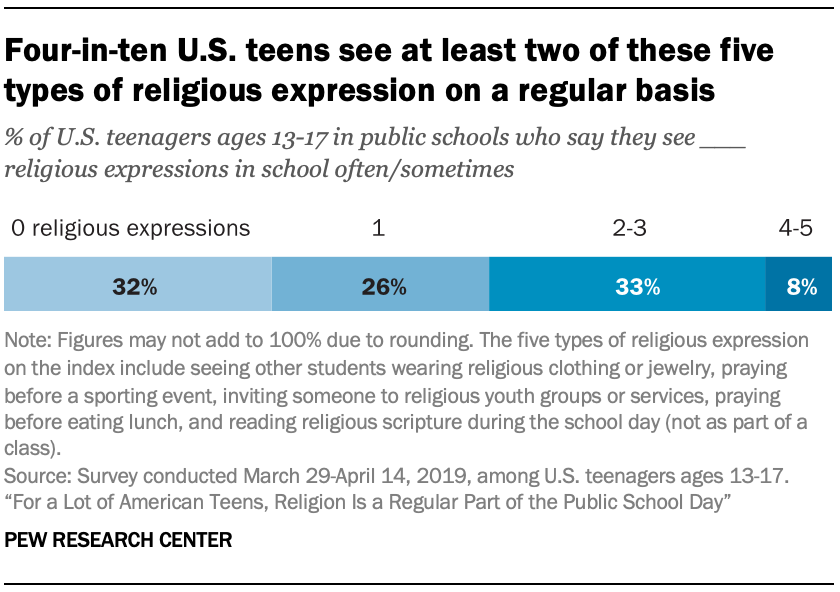

Overall, on an index combining these five types of religious expressions and activities by fellow students – wearing religious clothing or jewelry, praying before a sporting event, inviting other students to youth groups or services, praying before eating lunch, and reading religious scripture during the school day – 8% of teens in public schools say they commonly see all five (3%) or four out of five (5%). A third of students say they often or sometimes see two (20%) or three (13%) of these forms of religious expression in their public school, while 26% say they commonly see just one. And a third of public school teens (32%) say they rarely or never see any of these religious expressions by fellow students (or they did not answer the questions).

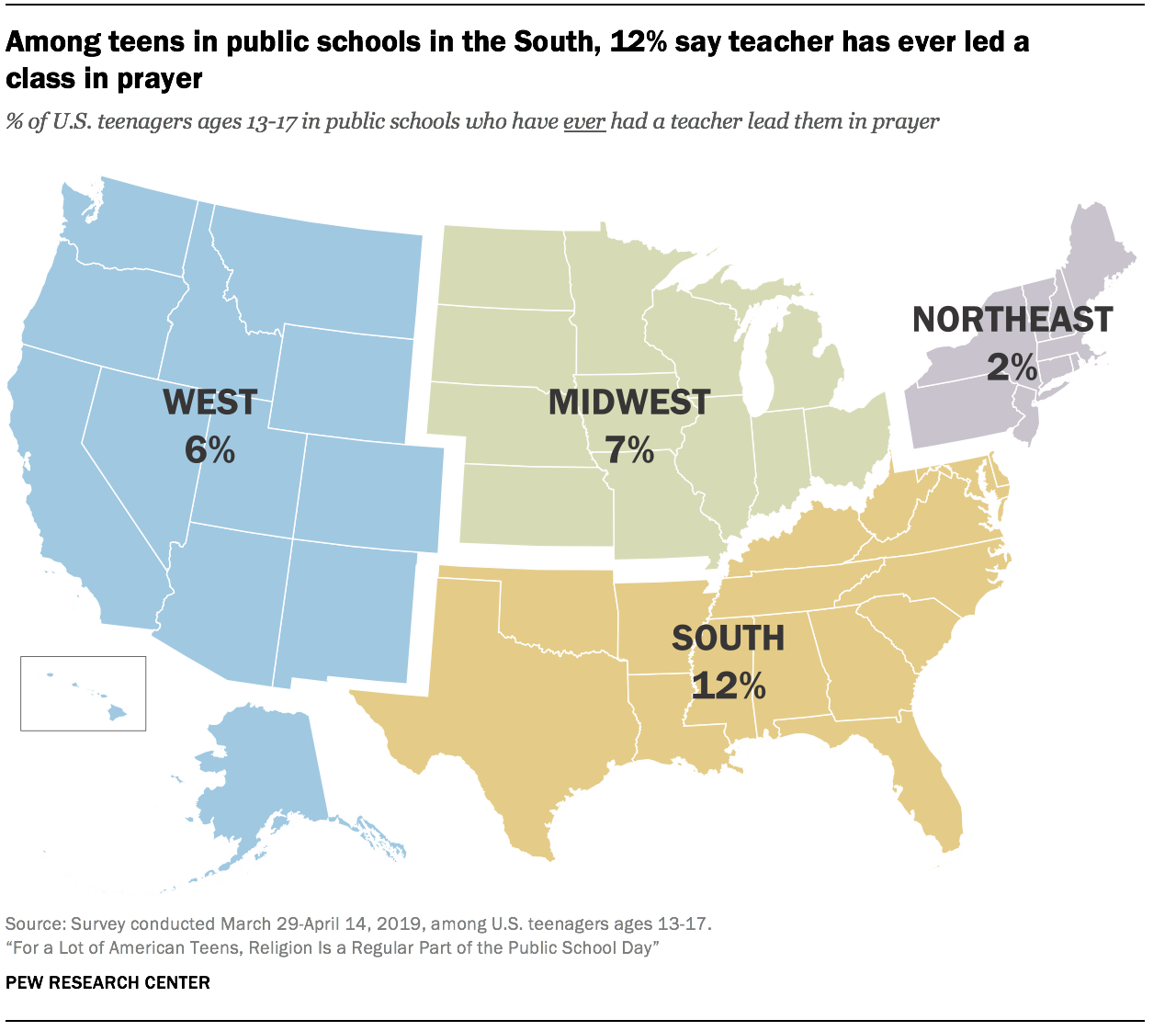

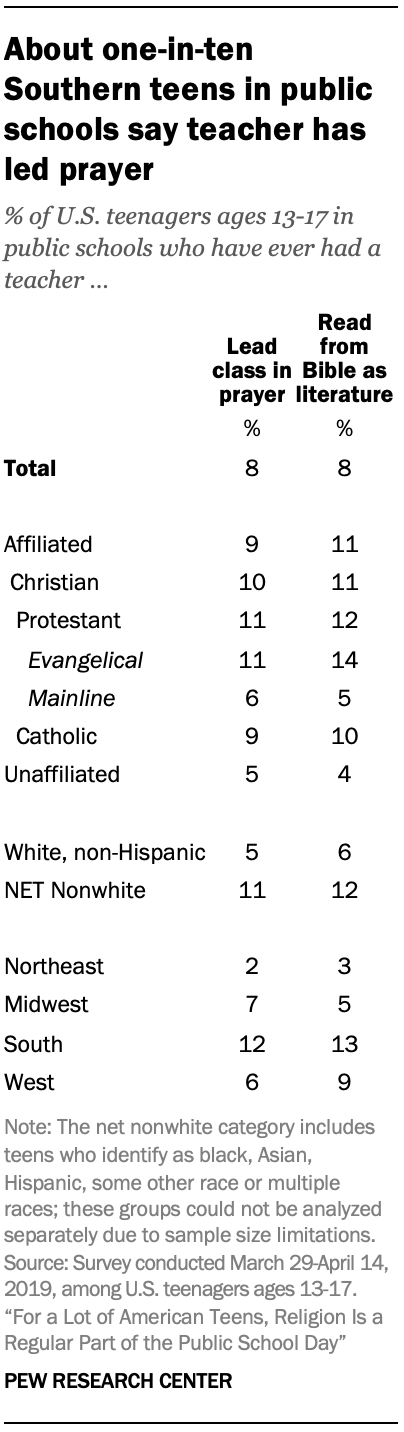

The survey also asked about two kinds of teacher-led, classroom activities. It finds that 8% of public school students say they have ever had a teacher lead their class in prayer – an action that the courts have ruled is a violation of the Establishment Clause of the Constitution.1 An identical share (8%) say they have had a teacher read from the Bible as an example of literature, which the courts have said is fine. Both of these experiences are more common in the South (where 12% of public school students say a teacher has led their class in prayer, and 13% say a teacher has read to them from the Bible as literature) than in the Northeast (where just 2% say a teacher has lead them in prayer, and 3% say a teacher has read from the Bible as an example of literature).

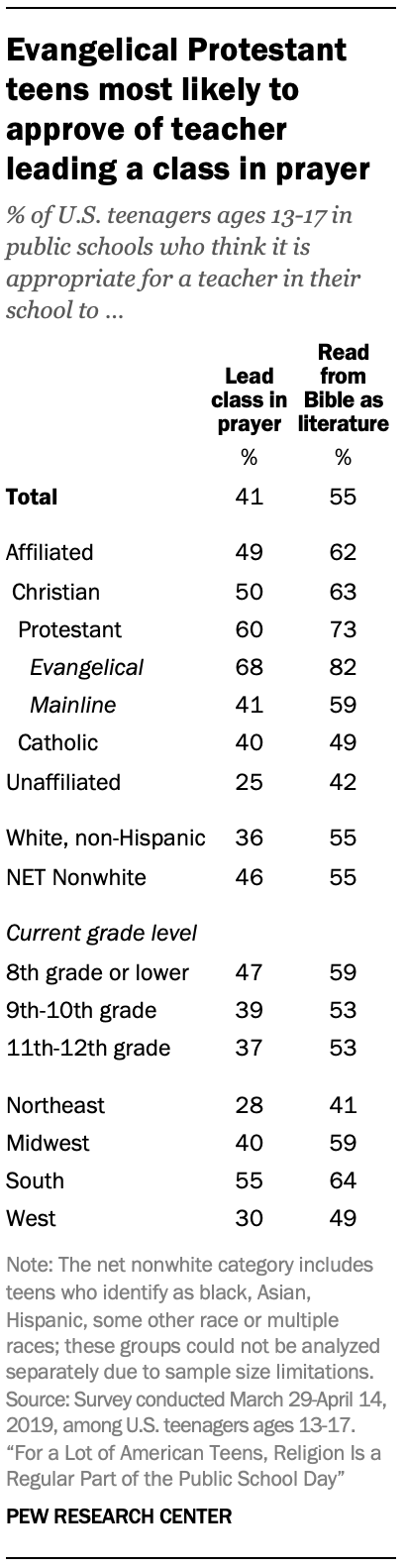

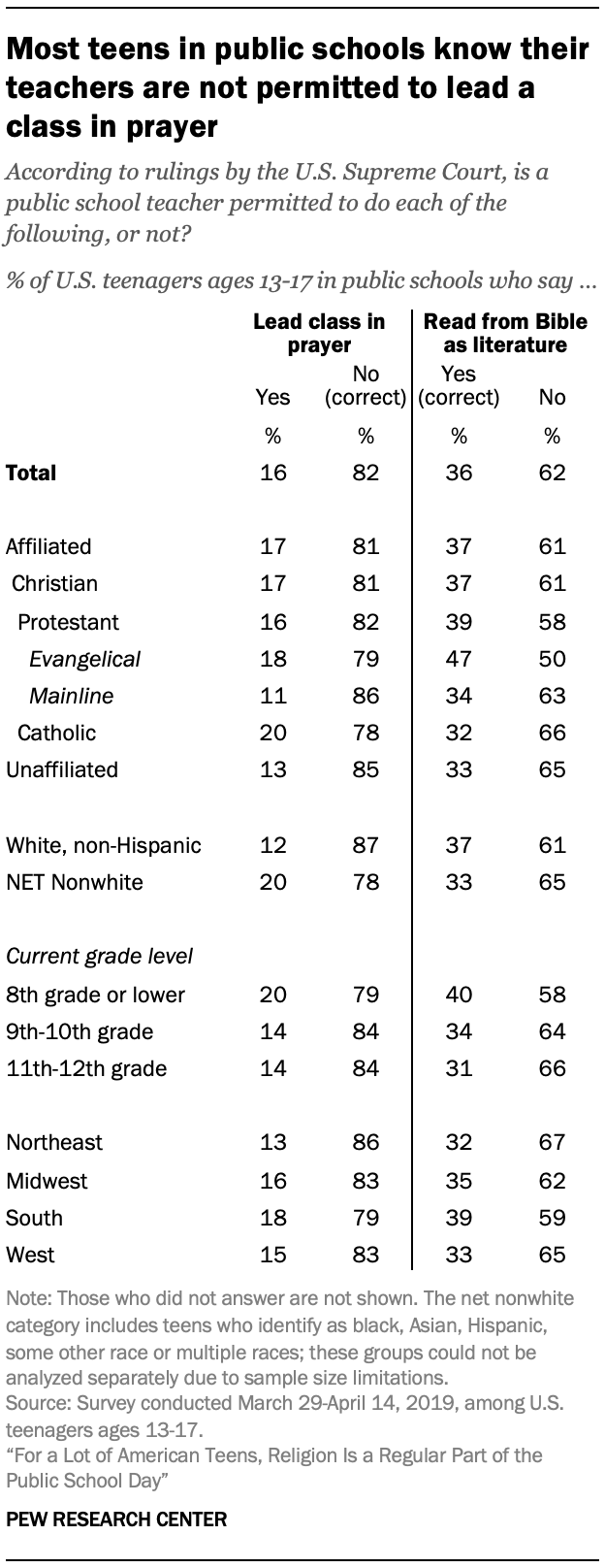

Nationwide, roughly four-in-ten teens (including 68% of evangelical Protestant teens) who go to public school say they think it is “appropriate” for a teacher to lead a class in prayer. Some of the teens who express this view are unaware of the Supreme Court’s ruling. But most know what the law is; 82% of U.S. teens in public schools (and 79% of evangelical teens) correctly answer a factual question about the constitutionality of teacher-led prayer in public school classrooms. Just 16% of teens incorrectly believe that teacher-led prayer is allowed by law, far fewer than the 41% who say it is “appropriate.”

Put another way, roughly half of teens who attend public school (53%) know that teacher-led prayer is prohibited and also find the practice inappropriate. At the same time, roughly three-in-ten (29%) know that it is unconstitutional but say that it is appropriate for a public school teacher to lead a class in prayer. Smaller shares think that teacher-led prayer is both legally permitted and appropriate (11%) or that it is permitted but inappropriate (4%).2

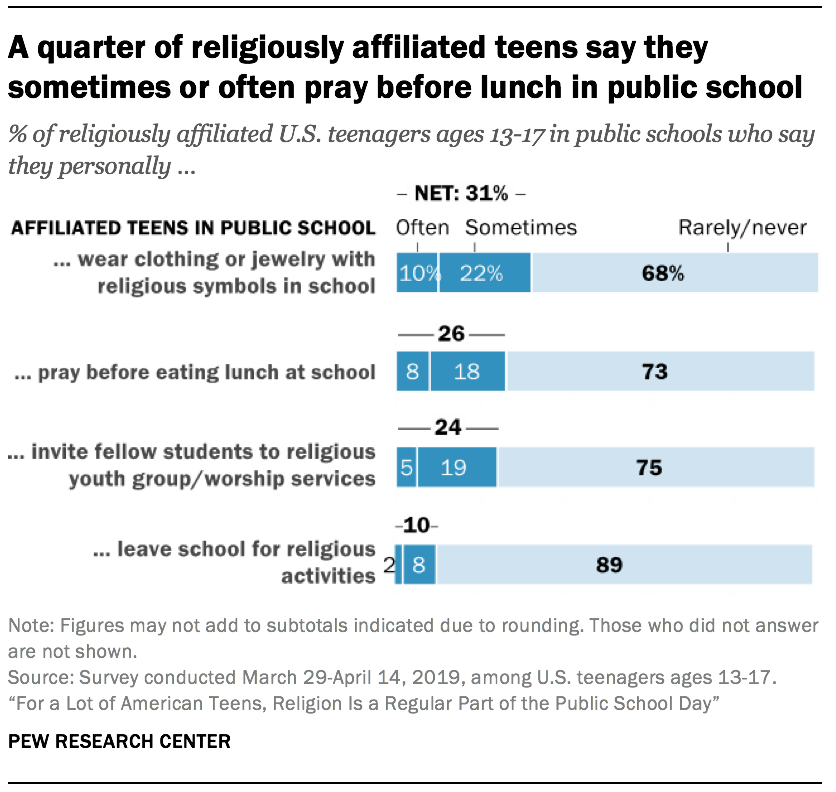

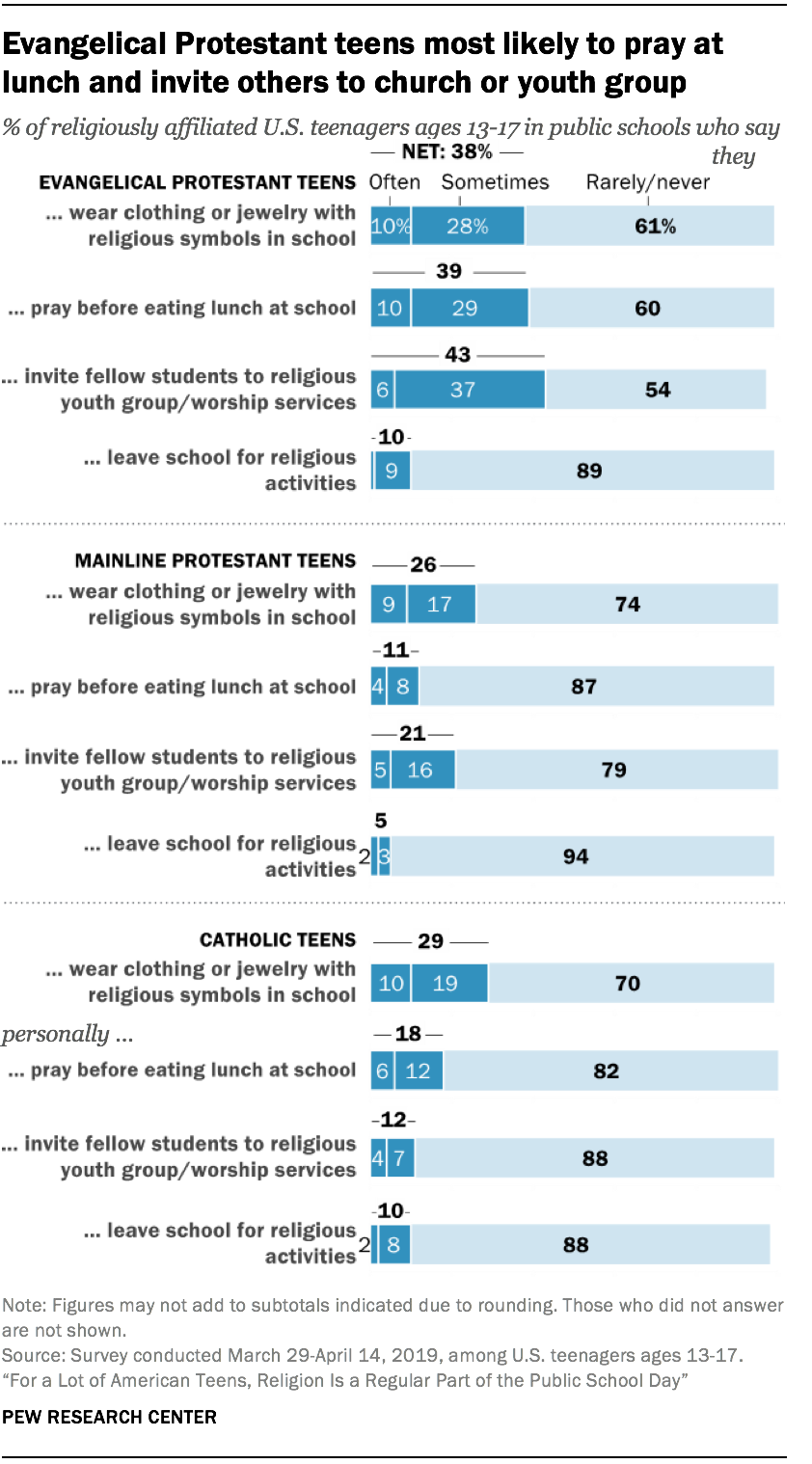

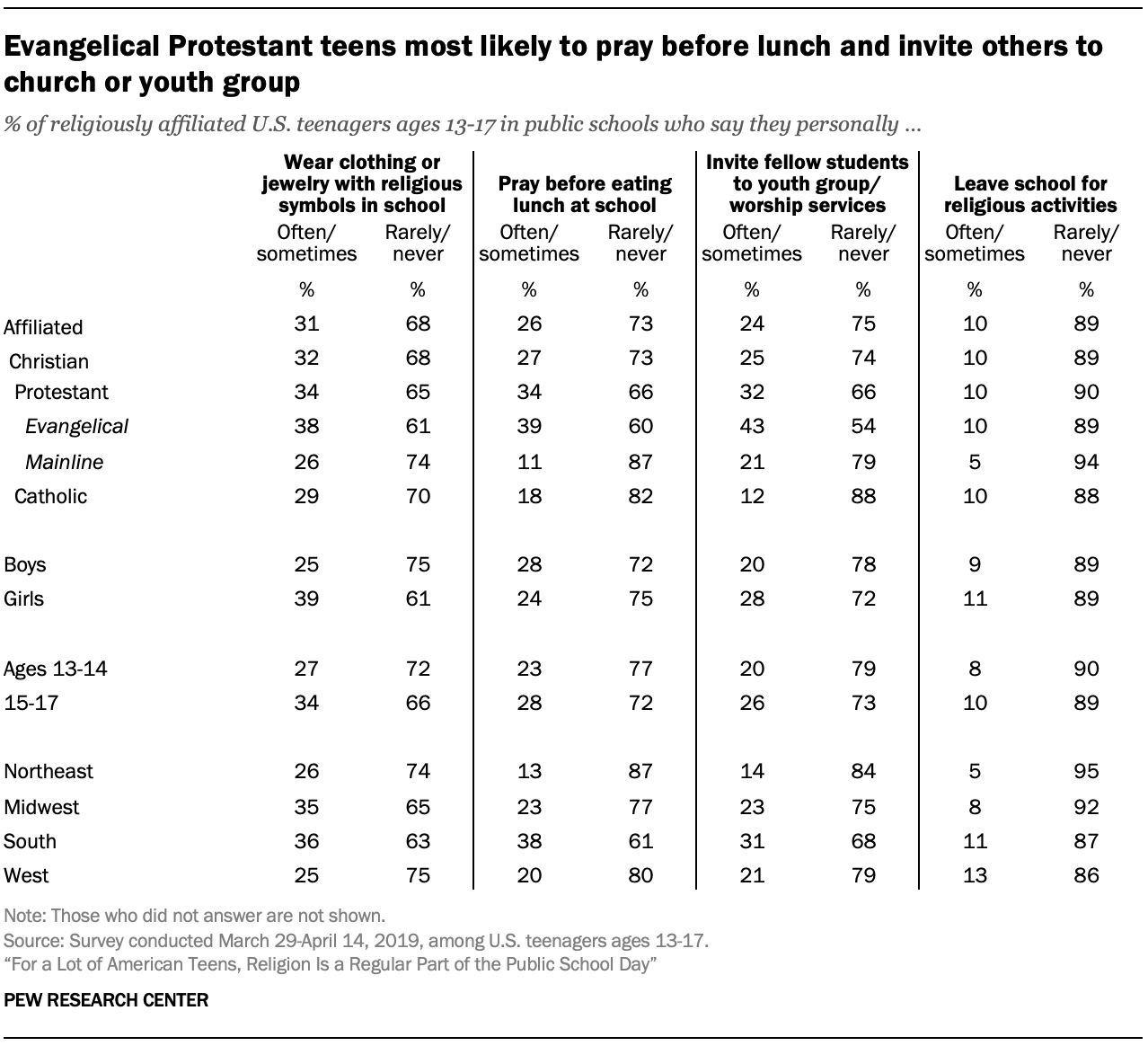

In addition to asking about what they have seen in school, the survey also asked teens who identify with a religion and attend a public school whether they personally participate in religious expressions in their school. Roughly three-in-ten or fewer say they regularly wear jewelry or clothing with religious symbols, pray before lunch, invite other students to worship services or a youth group, or leave school during the day to participate in religious activities.

To be sure, some religiously affiliated public school students do many of these four things on a regular basis: 12% say they sometimes or often participate in three or more of these religious expressions at school. But roughly half (49%) of the students surveyed say they rarely or never participate in any of these religious expressions during the school day, or they did not answer the questions. In addition, only 5% of all public school students say that there is a religious support or prayer group that meets in their school and that they have taken part in it in the past year. The vast majority say that as far as they know, there is no such group in their school.

An experience that is more common in American schools – both public and private – is bullying. The majority of U.S. teens surveyed say they either “often” (16%) or “sometimes” (38%) see students in their school being teased or made fun of. But this is rarely for religious reasons: Just 13% say they regularly see fellow students being teased because of their religion, and even fewer say they have directly experienced religiously motivated bullying. Overall, teens are far more likely to say they “rarely” or “never” see this type of bullying than they are to report that they sometimes or often witness such behavior.

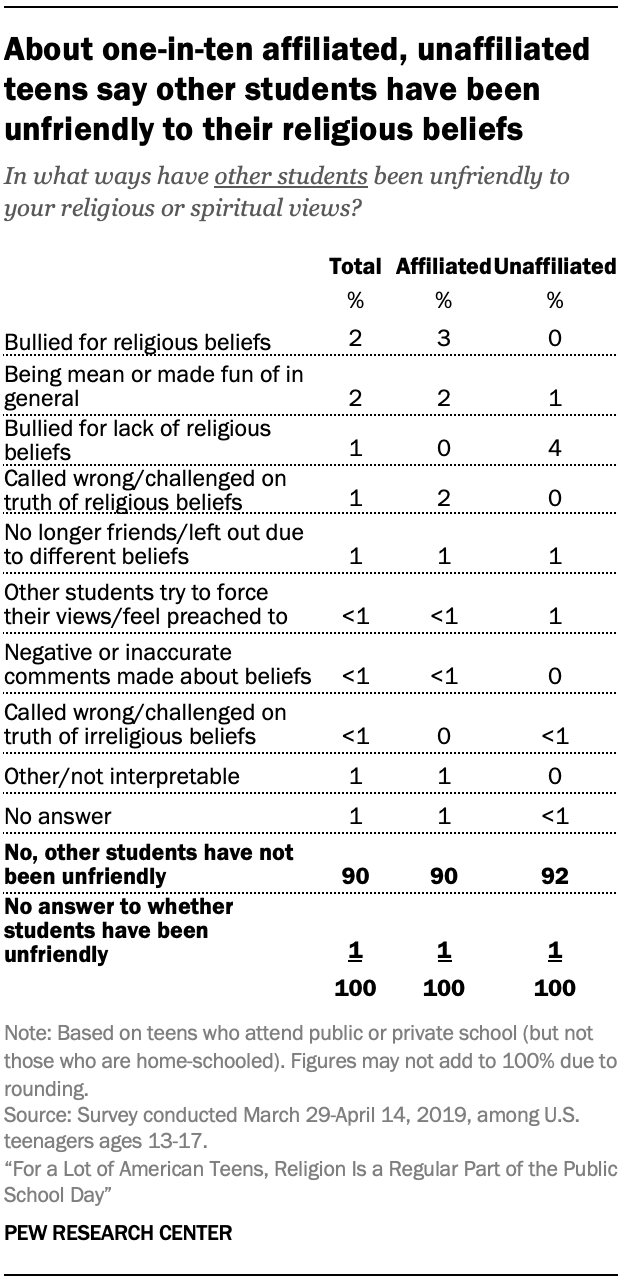

At the same time, roughly one-in-ten teens in public and private schools (9%) say that other students have made comments that are unfriendly to their personal religious or spiritual views, and 5% say that teachers have made such comments.

These are among the key findings of a survey of 1,811 U.S. adolescents ages 13 to 17, conducted online from March 29 to April 14, 2019. The survey was administered using the Ipsos KnowledgePanel and asked questions of both a teenager and one of their parents; this report focuses on the responses of the teens. For more information on how this survey was conducted, see the Methodology.

While several previous surveys have examined the religious lives of teenagers, this is the first large-scale, nationally representative survey asking teens a series of questions about their own practices and perceptions regarding religious expressions in public schools.

This topic is important to the broader study of religion in American society because of the friendships adolescents form in their classes and the way they experience religion in public spaces during some of their most formative years.3

The survey included teens from many religious backgrounds, including non-Christian faiths, such as Judaism, Islam, Buddhism and Hinduism. However, the sample of 1,811 teens did not include enough teens in those religious groups – or in some of the smaller Christian traditions, such as the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (sometimes called Mormons) or the historically black Protestant tradition – to allow their views to be analyzed and reported separately. The sample size is sufficient, though, to allow separate analysis of Catholic, evangelical Protestant, mainline Protestant and religiously unaffiliated teens.

Other findings in this report include:

- Teens who identify as evangelical Protestants are much more likely than Catholics and mainline Protestants to participate in religious activities in their public school, such as praying before lunch or inviting other students to their worship services or a religious youth group. For example, among teens who attend public schools, 39% of evangelical Protestants say they sometimes or often pray before lunch, compared with 18% of Catholics and 11% of mainline Protestants who say they do this.

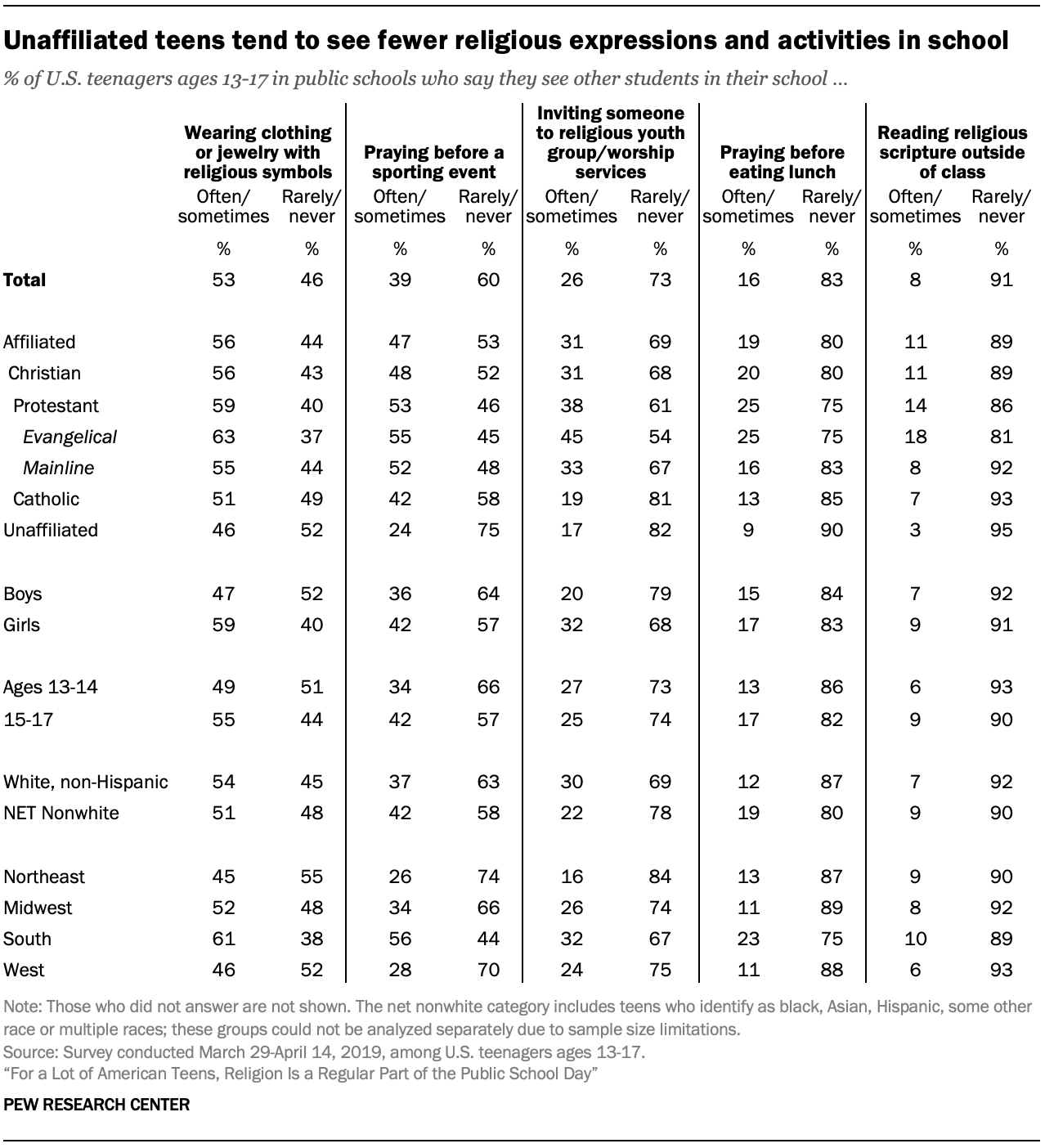

- Teens with no religious affiliation – those who identify as atheist, agnostic or “nothing in particular,” sometimes called religious “nones” – are less likely than others to notice religious activities in their schools. For instance, just 17% of unaffiliated teens say they sometimes or often see other students invite someone to worship services or a religious youth group, compared with three-in-ten Christian teens (31%) who commonly see this happen. These differences may reflect their circles of friends, the schools they attend, their attentiveness to religious behavior, or other factors.

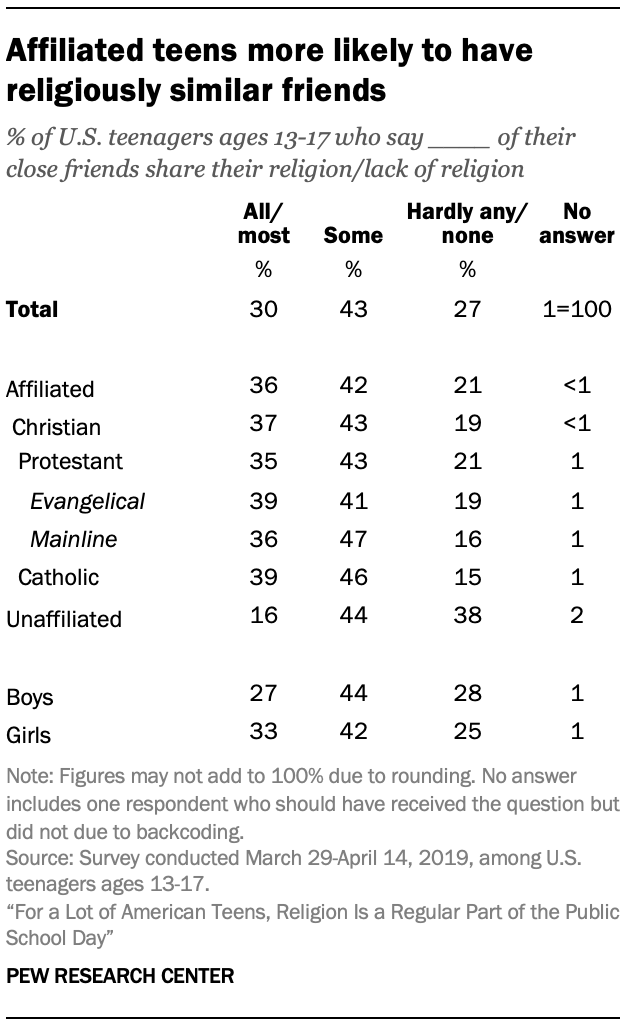

- About three-quarters of all religiously affiliated teens (78%) report that at least some of their friends share their religion. A smaller proportion (60%) of all religiously unaffiliated teens say they have friends who identify – like they do – as atheist, agnostic or nothing in particular. Indeed, 19% of unaffiliated teens say that none of their friends are religiously unaffiliated, and an additional 19% say that “hardly any” of their friends share their lack of religious affiliation.

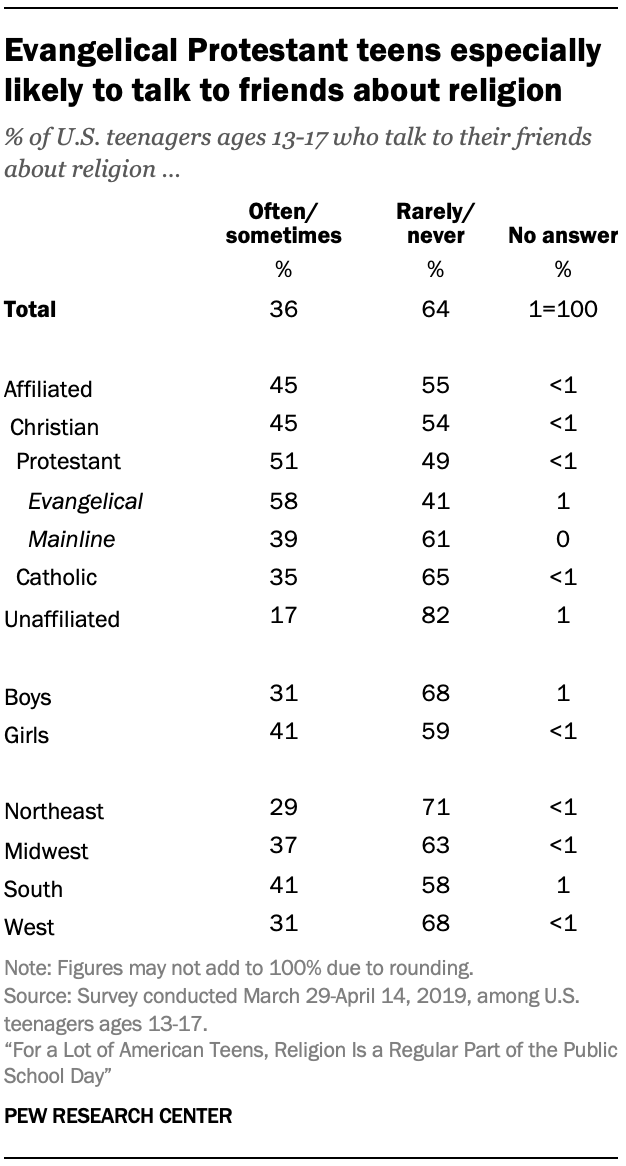

- Most American teens (64%) say they rarely or never discuss religion with their friends, and only 5% say they often engage in such discussions. Again, evangelical Protestants are much more likely than others to engage in this type of religious behavior; roughly six-in-ten evangelical teens say they sometimes (47%) or often (11%) talk to their friends about religion, compared with four-in-ten mainline Protestant teens, a third of Catholics and about one-in-five religious “nones” who at least sometimes discuss religion with friends.

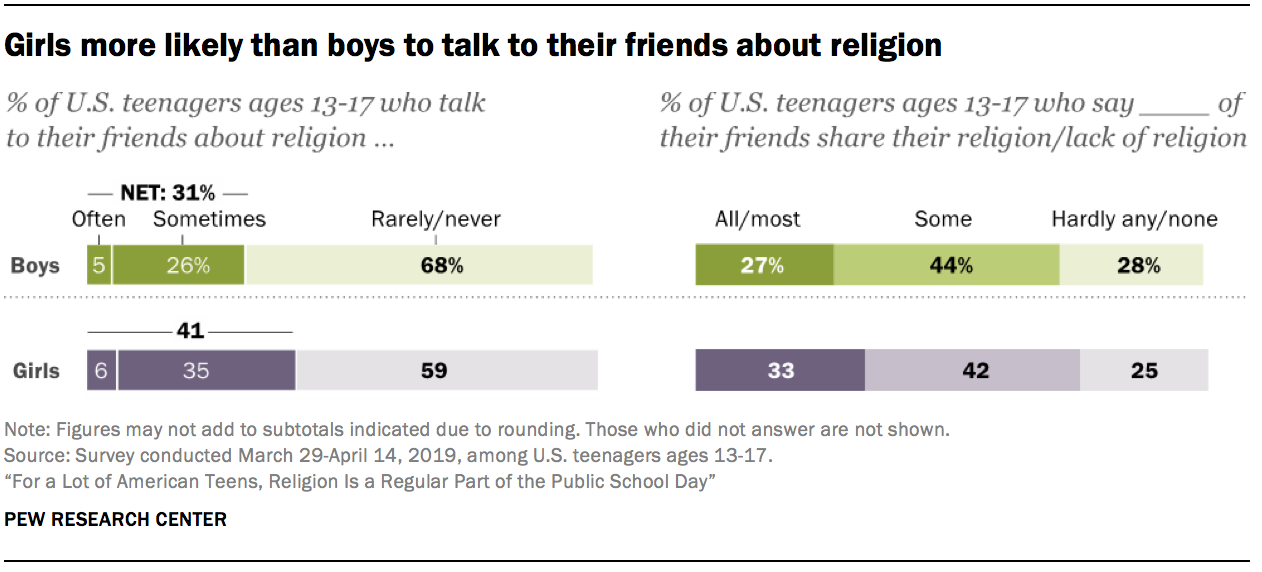

- Religion seems to play a somewhat larger role in friendships for adolescent girls than for boys. The survey shows that girls are more likely than boys to talk to their friends about religion (41% vs. 31%) and somewhat more likely to be religiously similar to most of their friends. Girls who attend public school also are more likely to notice when other students wear clothing or jewelry with religious symbols and to invite other students to their religious youth group or worship services. This reflects a broader pattern among adults: Women are generally more religious than men, particularly among Christians.

- Just 1% of mainline Protestant teens say they have ever been teased or made fun of in school for their religion, compared with 9% of Catholic teens and 10% of evangelicals who say the same.

The rest of this report explores findings from the survey’s questions about religion in school and among teenagers’ friendship circles in more detail, including analysis by religious group, age and grade level, race or ethnicity, gender, and geographic region.

Religion in school

Most teens surveyed attend public schools, fewer attend private schools or are home-schooled

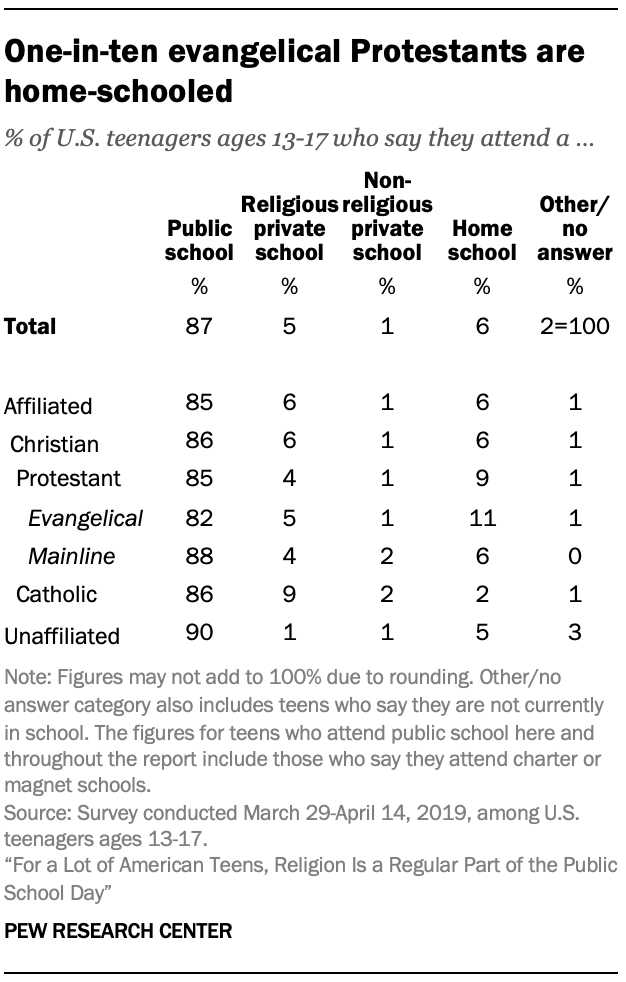

The vast majority (87%) of teenagers surveyed say they attend public schools.4 An additional 5% attend religious private schools, while 6% are home-schooled. Just 1% attend a nonreligious private school.5

However, the type of school adolescents attend tends to vary depending on their self-described religious background. Teens who describe themselves as evangelical Protestants are more likely to be home-schooled (11%) than “nones” (5%) and Catholics (2%). And, not surprisingly, teens with a religious affiliation (6%) are more likely than those without one (1%) to attend a religious private school. The survey indicates that Catholic teens are more likely than Protestant teens (9% vs. 4%) to attend a religious school.

Most of the analyses in this report are limited to teenagers who attend a public school. When it comes to experiences with religion in a school environment, adolescents who attend religious schools or are home-schooled are much different from those who do not, and the survey did not include sufficiently large samples of students who attend religious private schools, or who are being home-schooled, to compare these groups with teenagers who go to public schools.6

Most U.S. teens commonly see at least one type of religious expression in public school

Some religious expressions are relatively common in public schools. For instance, about half (53%) of U.S. teens in public schools often or sometimes see other students wearing clothing or jewelry with religious symbols, and four-in-ten (39%) regularly see students praying before a sporting event.

Other religious activities and expressions are less common. A quarter of teens in public schools (26%) say they often or sometimes see students inviting other students to religious youth groups or worship services. About one-in-six (16%) regularly see other teens praying before lunch, and 8% often or sometimes see students reading religious scripture outside of class. This means that large majorities of U.S. teens rarely or never see these behaviors in school.

On an index combining all five of these types of religious expression in school, about a third of teens (32%) say they rarely or never see any of them (or they did not answer the questions), while just 3% say they see all five on a regular basis. Another way to sum up their experiences: On the one hand, a majority of teens (68%) report seeing at least one of these religious expressions or activities in their public schools often or sometimes; on the other hand, fewer than half (41%) say they commonly see more than one of these religious behaviors.

There are substantial differences in what students tend to see in public school depending on the student’s religious affiliation. Religiously affiliated teens are more likely than unaffiliated teens to say they at least sometimes see each of the five types of religious activities or expressions in school. There also are differences among religiously affiliated teens. For instance, Protestant teens (38%) are twice as likely as Catholic teens (19%) to say they see students inviting other students to youth group or worship services at least sometimes. And there are differences even among Protestants: Evangelical Protestant teens (18%) are twice as likely as mainline Protestants (8%) to say they regularly see their peers reading religious scripture in school.

It is not completely clear what accounts for such large differences in what adolescents see in their schools. It is possible that the tendency to have religiously similar friendship circles (see here) affects what students see.7 For example, religious teens – who tend to have friends who are similarly religious – may be exposed to more religious activities and expressions. But it’s also possible that religious and nonreligious teens may perceive the world somewhat differently: What may appear as a religious expression to an evangelical Protestant teen may not even be noticed by a nonreligious teen. Yet another factor is that certain groups are concentrated in parts of the country where religious expressions may be more (or less) common.

Indeed, geographic region of residence is also associated with how likely teens are to witness religious activities and expressions in school. Teens in the South – where adults, on average, are more religious than in other regions – are particularly likely to report seeing religious expressions in school. About a quarter (23%) of Southern teens often or sometimes see other students praying before lunch, compared with 13% in the Northeast and 11% in both the Midwest and West.

Public school students in the South also are more likely than those in other regions to report seeing students pray before sporting events and wear clothing or jewelry with religious symbols.

There also are gender, age, and racial and ethnic differences in what adolescents experience in school. Girls are more likely than boys to see students wearing religious jewelry or clothing as well as more likely to see students inviting other students to religious services or youth group. Older adolescents are especially likely to say they “often” or “sometimes” see students pray before sporting events. And white (non-Hispanic) teens are more likely than nonwhite teens to see students inviting other students to youth groups or services.8

Aside from what they see in school, what are adolescents doing in school, religiously speaking?

The survey asked religiously affiliated teens about their own religious practices and expressions in school. Among public school teens who identify with a religion, 31% say they at least sometimes wear clothing or jewelry with religious symbols, and about a quarter say they sometimes or often pray before lunch (26%) or invite other students to their worship services or a religious youth group (24%).9 One-in-ten religiously affiliated teens say they regularly leave school for religious activities or programs.

Evangelical Protestants stand out on some of these measures. Roughly four-in-ten evangelical Protestant teens who attend public school say they at least sometimes pray before lunch at school (39%), compared with 18% of Catholic teens and 11% of mainline Protestant teens. Similarly, about four-in-ten evangelical teens (43%) say they sometimes or often invite other students to their worship services or youth group, compared with 21% of mainline Protestants and 12% of Catholics who say they do this. Evangelical Protestant adolescents (38%) also are more likely than mainline Protestants (26%) to regularly wear religious clothing or jewelry.

There are differences between boys and girls on some of these measures. While four-in-ten religiously affiliated girls (39%) sometimes or often wear religious jewelry or clothing, a quarter of religiously affiliated boys (25%) do so. This may be due to overall differences in the amount of jewelry that girls and boys wear; if girls wear jewelry more often than boys do in general, it stands to reason that they would also wear religious jewelry more often. But there also are gender differences when it comes to inviting fellow students to church or youth group: Nearly three-in-ten girls (28%) report that they sometimes or often invite others to their youth group or worship services, compared with one-in-five boys (20%).

Religious activities and expressions in public schools vary by region, too. Religiously affiliated teens in the South (38%) are more likely than those in the Midwest (23%), West (20%) and Northeast (13%) to report praying before lunch at school. Southern teens (31%) also are more likely than teens in the West (21%) and Northeast (14%) to invite other students to their youth group or worship services.

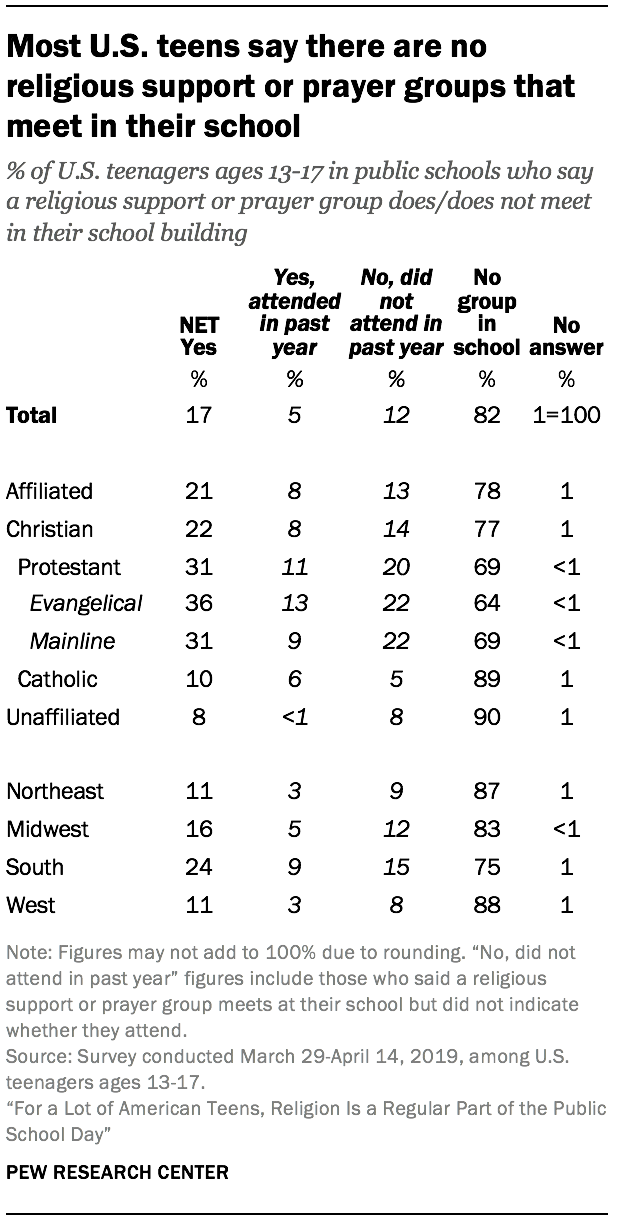

Most teens do not have religious support groups in school

The vast majority of U.S. teens who attend public schools say there is no religious support group or prayer group that meets in their school (82%). Nearly one-in-five teens say that religious support or prayer groups do meet in their schools (17%), including 5% who say they have participated in such a group in the last year and 12% who have not done so.

Among Protestant teens, roughly three-in-ten (31%) say that a religious support group or prayer group meets in their school. But far fewer Catholics and religious “nones” say the same: Only about one-in-ten Catholic and unaffiliated teens report that their school hosts such a group.10

Unaffiliated teens also are highly unlikely to attend a support group, with fewer than 1% saying they have done so in the past year (the question was intended to capture nonreligious groups as well, such as the Secular Student Alliance). Protestant teens are somewhat more likely than their Catholic peers to participate in religious or prayer groups in school (11% vs 6%).

Teens’ awareness of, and attendance at, religious support or prayer groups at their school also varies by region, with teens in the South more likely to say that prayer or religious support groups meet in their public school and that they, personally, participate in such activities, compared with those in the Northeast and West. Still, just 9% of Southern teens who go to public school say that in the past year they have attended a prayer group or religious support group (such as the Fellowship of Christian Athletes) that meets in their school.

Religion in the classroom relatively rare

Relatively few U.S. teens in public schools report that they have ever seen teachers either lead a class in prayer (8%) or read from the Bible as an example of literature (8%).11

Protestant teens (11%) are more likely than unaffiliated teens (5%) to report that a teacher has led their class in prayer, and to report that a teacher has read from the Bible as an example of literature (12% vs. 4%).

Adolescents’ reports of teachers’ religious activities in the classroom also vary by race and ethnicity and region. Nonwhite teens are more likely than white (non-Hispanic) teens to say a teacher has led their class in prayer (11% vs. 5%) and read from the Bible as literature (12% vs. 6%). And teens in the South are especially likely to say a teacher has led their class in prayer (12%) and read from the Bible (13%) when compared with the small shares of teens in the Northeast who report the same (2% and 3%, respectively).

Gender, age and grade are not associated with having seen teachers lead a class in prayer or read from the Bible as literature.

What do students in public schools think about teachers leading a class in prayer or reading from the Bible as an example of literature?

About four-in-ten (41%) say they think it is appropriate for a teacher in their school to lead a class in prayer, and 55% say it is appropriate for a teacher to read from the Bible as an example of literature. But there are large differences by religion.

Among those in public schools, religiously affiliated students (49%) are about twice as likely as religious “nones” (25%) to think it is acceptable for a teacher to lead a class in prayer. Affiliated adolescents also are more likely than “nones” to think it is acceptable for a teacher to read from the Bible as literature (62% vs. 42%).

There are large differences among religiously affiliated adolescents as well. For instance, six-in-ten Protestants approve of a teacher leading a class in prayer, compared with four-in-ten Catholics who say this. Evangelical Protestants are especially likely to approve of teachers bringing religion into the classroom: Two-thirds of evangelical Protestant teens (68%) say it is appropriate for a teacher to lead a class in prayer, compared with four-in-ten mainline Protestants (41%). Roughly eight-in-ten evangelical Protestant teens approve of a teacher reading from the Bible as an example of literature (82%), compared with six-in-ten mainline Protestant teens who say this (59%).

Views toward teachers bringing religion into the classroom also vary across racial and ethnic groups, regions, and grade levels. Nonwhite teens are more supportive of teachers praying: 46% of nonwhite teens think it is appropriate for teachers in public schools to lead a class in prayer, while 36% of non-Hispanic white teens think so. But there are no differences between white and nonwhite teens in views toward teachers reading from the Bible as an example of literature.

Teens in the South and Midwest are particularly likely to approve of teachers praying and reading from the Bible in class. About half (55%) of Southern teens in public schools say it is appropriate for a teacher to lead a class in prayer. By comparison, three-in-ten teens in the West (30%) and Northeast (28%) think it is acceptable for a teacher to lead a class in prayer. There is a similar pattern on the question about teachers reading the Bible as literature.

Teens who have been in school for more years are less supportive of teachers praying in the classroom. Nearly half (47%) of pre-high school teens think it is appropriate for a teacher to lead a class in prayer, compared with 37% of those in 11th and 12th grades.

The survey also asked teens what they know about the U.S. Supreme Court’s stance on teacher-led prayer, finding that those in 8th grade or lower are more likely than those in 9th through 12th grades to incorrectly say that the court permits the practice (20% vs. 14%).

Overall, most U.S. teens in public schools (82%) know that their teachers are not permitted to lead a class in prayer, according to rulings by the U.S. Supreme Court. At the same time, 16% think this is legally allowed – although this is much smaller than the share who think it would be appropriate (41%). Among just those who say teacher-led prayer is appropriate, a somewhat higher share believe it is permitted by law (28%), but 70% still know that it is unconstitutional.

U.S. teens are much less familiar with the law when it comes to reading from the Bible as an example of literature, which the Supreme Court has ruled permissible. About a third (36%) of U.S. teens in public school know that their teachers are permitted to do this, while six-in-ten (62%) think it is not allowed.

Evangelical Protestant teens stand out from other traditions on this measure: 47% know that public school teachers are allowed to read from the Bible as literature, compared with about a third each of mainline Protestant teens (34%), religious “nones” (33%) and Catholics (32%).

In contrast with the question about teacher-led prayer, teens in 11th and 12th grades are less likely to correctly answer this question than those in eighth grade or lower.

There are no statistically significant differences across regions on either of these questions.

Relatively few teens witness religion-related bullying in schools

To further explore what teens are encountering in their schools, the survey asked about experiences with teasing, bullying and being subject to unfriendly comments. The analyses of bullying and hostility toward religion in school include students in both religious and nonreligious schools (but not those who are home-schooled). 12

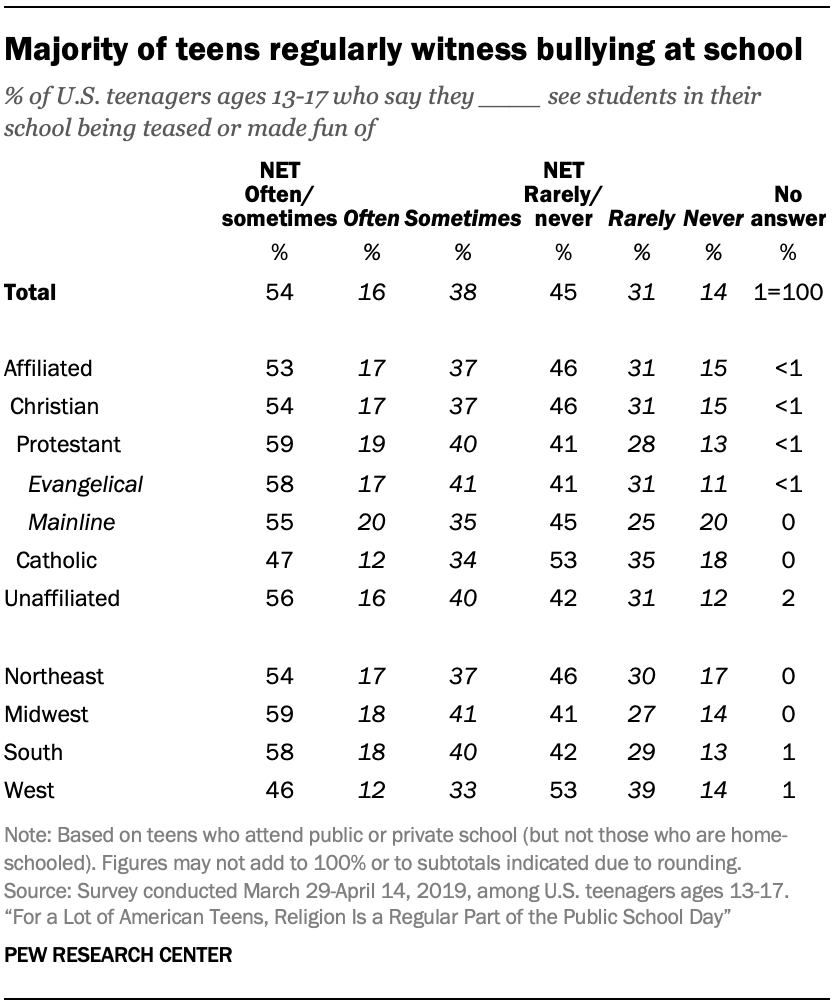

Many educators, parents, and researchers have pointed out that bullying is a major concern in U.S. schools, and the new survey finds that 54% of U.S. teens report regularly seeing students in their school being teased or made fun of – including 16% who say they often see this and 38% who sometimes see it. About three-in-ten say they rarely witness bullying in school, while 14% say they never see it.

Christians and religious “nones,” boys and girls, and older and younger teens are all about equally likely to witness bullying in school. Teens who live in the Midwest (59%) and the South (58%) are somewhat more likely than those in the West (46%) to say they see other students being teased or made fun of in school with any regularity. But, on the whole, there is little variation in how often students in these various demographic categories report witnessing bullying.

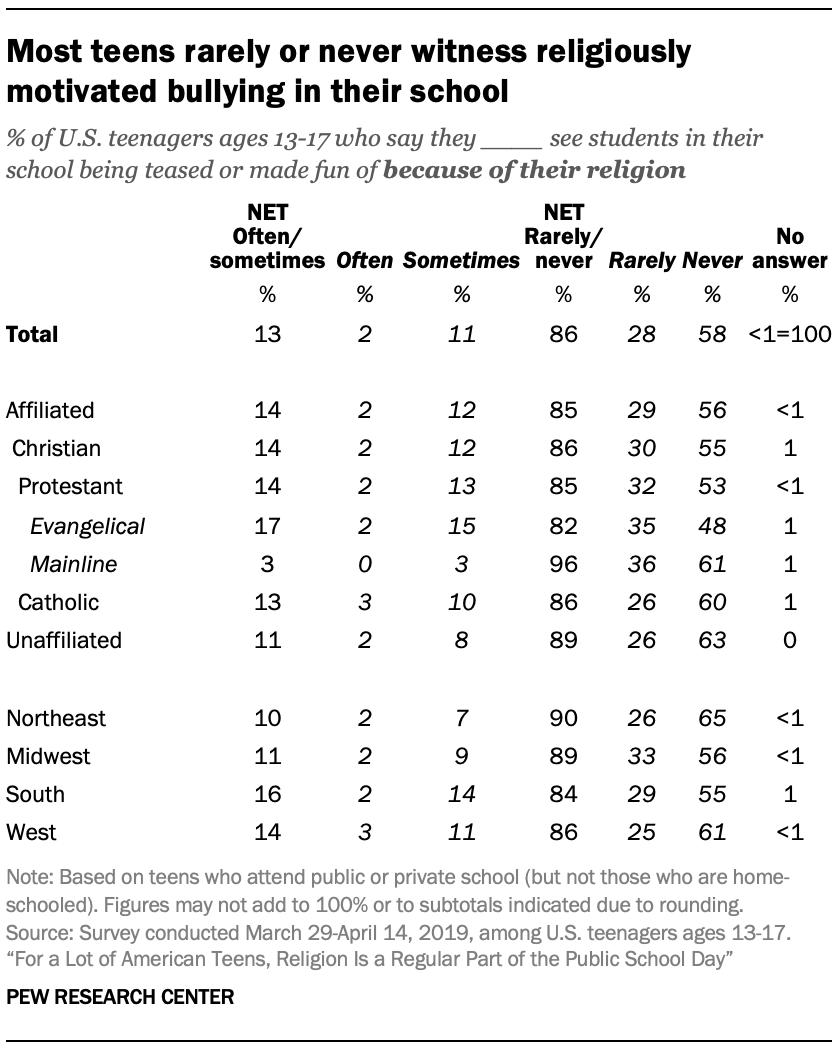

While many teens in both public and private schools observe bullying in their school, fewer say that they see other students being teased or made fun of because of their religion, specifically. In fact, six-in-ten (58%) say they never witness this type of behavior, and 28% say they rarely see it. One-in-ten say that they sometimes see religiously motivated bullying in their school (11%), and 2% see this often.

On this question, mainline Protestants stand out from other religious groups as being the least likely to say that they regularly see religious bullying in their school. Just 3% say they witness this behavior at least sometimes, compared with 11% among religious “nones,” 13% among Catholic teens and 17% among evangelicals. Evangelical teens are the least likely to say that they never see religious bullying in their school (48%).

Across many demographic groups, most school-attending teens rarely, if ever, see other students being bullied for their religion. There are virtually no differences between boys and girls, younger and older teens, or across regions on this question.

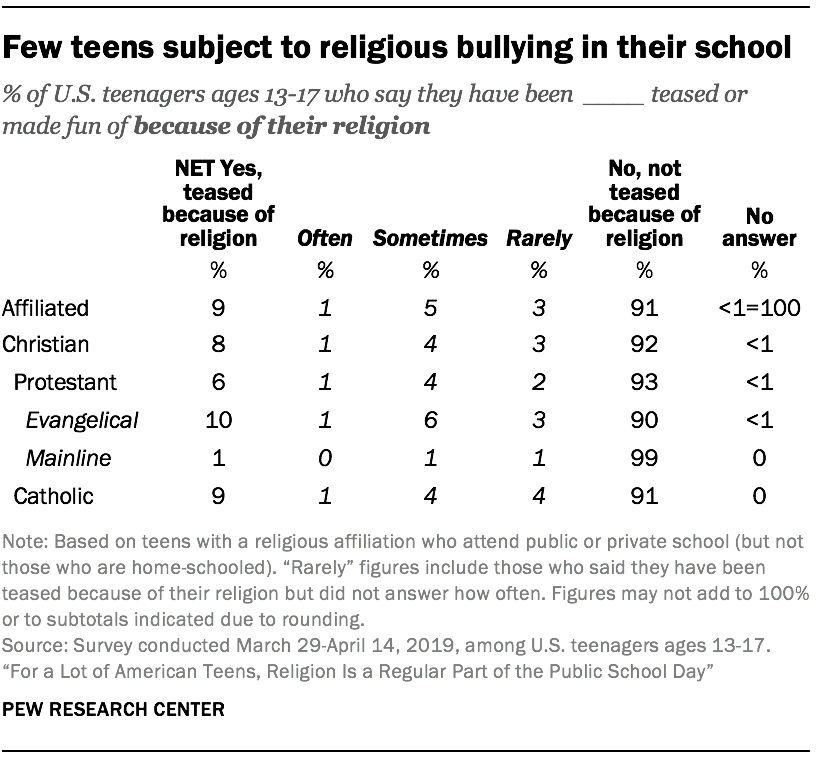

Among public or private school students who are affiliated with a religious tradition, roughly one-in-ten say that they, personally, have ever been teased or made fun of in school because of their religion.13

Just 1% of mainline Protestant teens say they have ever been bullied in school for their religion, compared with 10% of evangelicals and 9% of Catholic teens who say the same.

There are few discernible differences on this question among religiously affiliated teens by gender, age, and race and ethnicity. Roughly one-in-ten or fewer in each demographic group say they have personally been teased or made fun of in school because of their religion.

Unaffiliated teens were asked a similar question about being teased for their lack of religion. Among students who identify religiously as atheist, agnostic or “nothing in particular,” very few (4%) say they have personally experienced bullying in school because they are not religious.

The survey also asked teens whether other students have been “unfriendly” to their religious or spiritual views. Those who said “yes” then had the opportunity to explain, in their own words, how this has occurred, with the goal of getting more details about any religiously motivated bullying that teens may be facing in school.

Overall, about one-in-ten of all school-attending adolescents report that other students have been unfriendly toward their religious views. And they give a wide range of responses to demonstrate just what they are experiencing from their peers.

[they]

[say]

Equally small shares of both affiliated and unaffiliated teens (1% each) note that they have lost friends or felt distanced from former friends due to different beliefs.

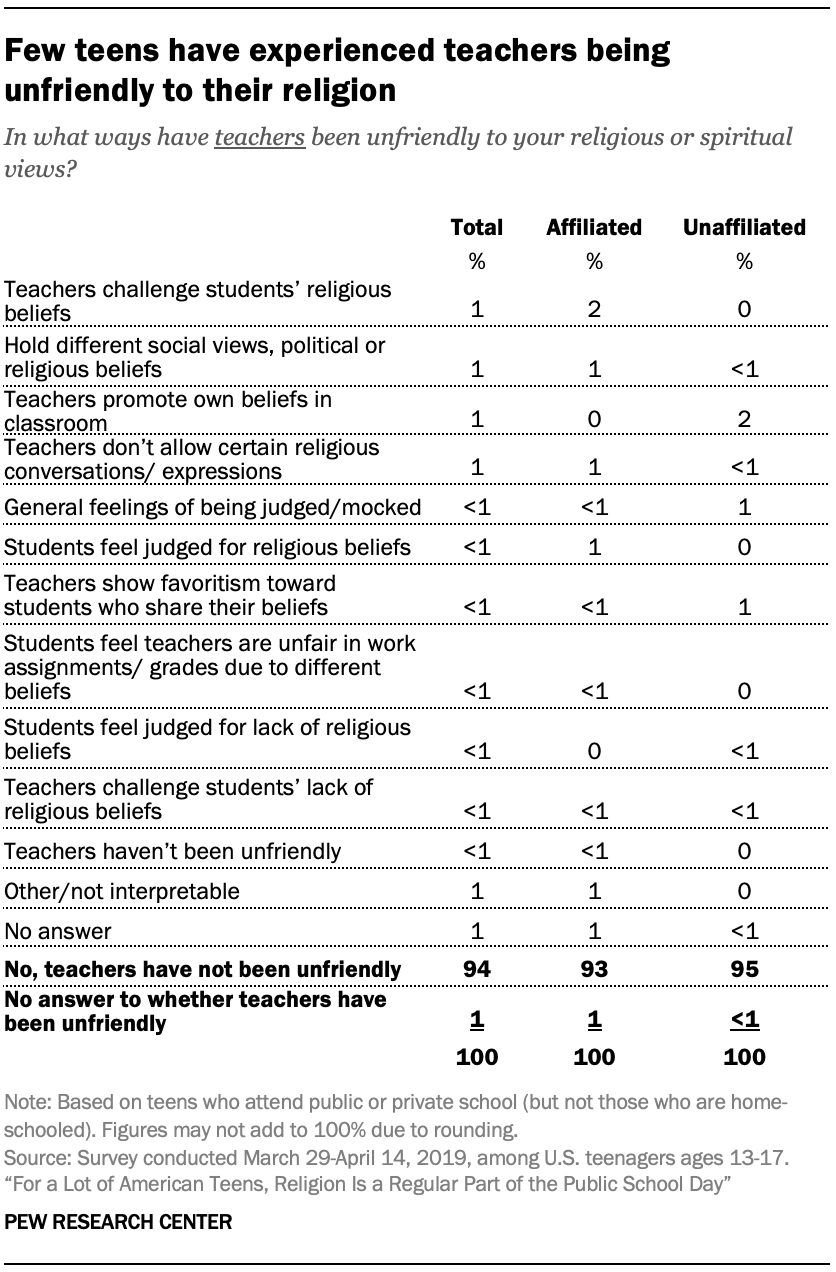

School-attending teens are slightly less likely to say that teachers have been unfriendly toward their religious or spiritual views than they are to say the same about other students (5% vs. 9%). Those who report that they have experienced this type of behavior by a teacher cite a variety of circumstances and ways in which it has happened.

Some teens who belong to a religion offer responses that indicate a teacher challenged the students’ religious beliefs, including questioning a student’s intelligence (2%). These teens report experiences such as, “I had a life science teacher once talk for 30 minutes about why religion is stupid and a joke” and “they’ve made fun of me and not supported me in going to my before school scripture study class.”

[the]

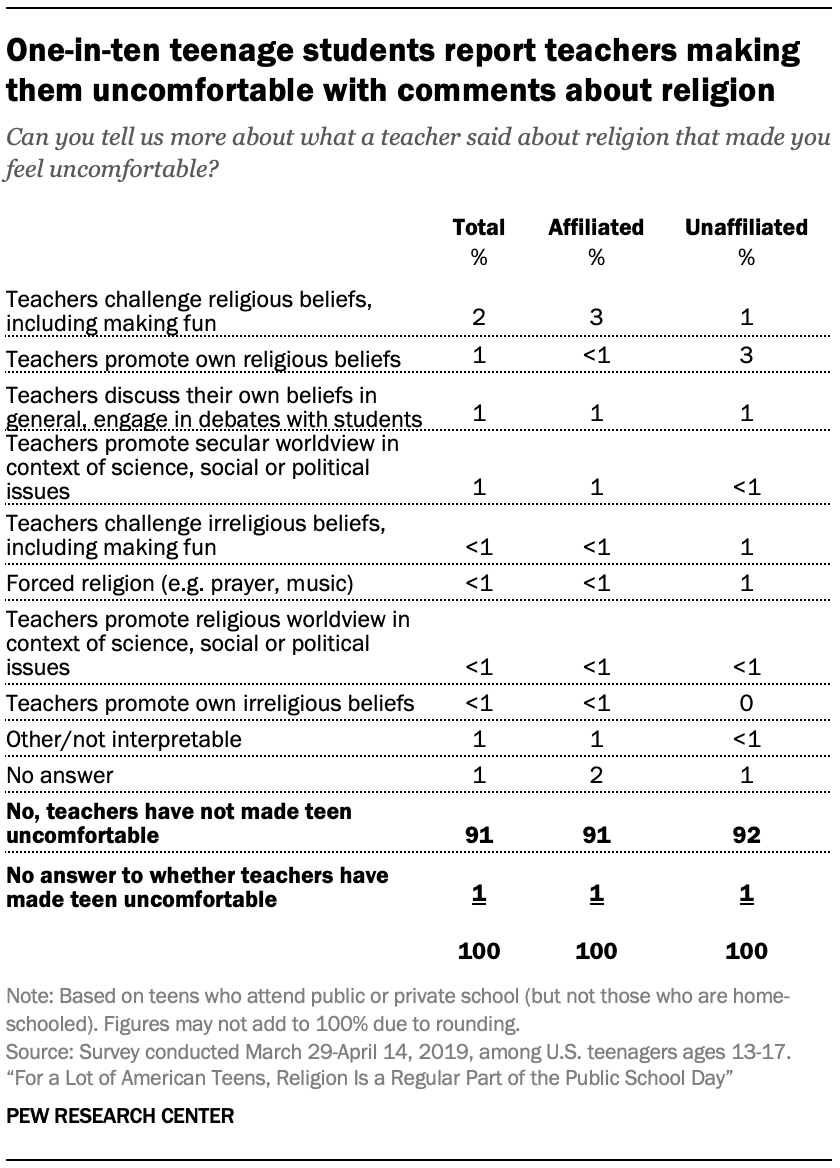

The survey also asked students a more general question: Has a teacher ever said anything about religion that made you feel uncomfortable? About one-in-ten students say they have experienced this type of discomfort in their schools, with some small distinctions between those who have a religion and those who do not.

[The teachers said]

Teenage friendships and religion

According to sociologists, religion is usually a social phenomenon, taking place among a community of believers.14 People affect – and are affected by – the religious and spiritual beliefs and activities of their friends and family. Contemporary research points to the idea that social interactions promote and maintain religious worldviews.15 And among teenagers, too, there is evidence that the friendships adolescents form in school influence their religious trajectories.16

Indeed, most teens have at least some friends who share their religion (or lack thereof). Overall, only about a quarter (27%) say that “hardly any” or “none” of their friends share their religion – or, in the case of unaffiliated respondents, that “hardly any” or “none” of their friends are atheist, agnostic, or have no particular religion. Three-in-ten teens report that most or all of their friends share their religion, and even more (43%) say some of their friends share their religious identity.

There is good reason to expect that this should vary by religion. Most Americans identify as Christians of some kind, meaning it may be harder for nonreligious adolescents to find friends who are like them, religiously. That is borne out by the data: Religiously affiliated teens as a whole are roughly twice as likely as religious “nones” (36% vs. 16%) to report that most or all of their friends share their religion (or lack thereof). About four-in-ten unaffiliated teens (38%) say that hardly any or none of their friends are, like them, atheist, agnostic or “nothing in particular” when it comes to religion.

Among adults, some religious groups are more likely than others to have friendship networks that reflect their own beliefs or affiliations.17 Protestants, for example, are overall less likely than Catholics, members of non-Christian faiths and religious “nones” to have interreligious social connections. But, unlike adults, Protestant adolescents are no more likely than Catholic teens to say that most or all of their friends share their religion.18

Aside from religious affiliation, region, age and grade play few, if any, statistically significant roles in the religious makeup of adolescents’ social networks. But gender is a factor. A third of girls (33%) report that most or all of their friends share their religious identity, making them moderately more likely than boys (27%) to be in that situation.

Most teens do not regularly talk to friends about religion

For most teens, religion is not a regular topic of conversation with friends. Roughly two-thirds (64%) say they rarely or never talk to their friends about religion. Still, a sizable minority of American teenagers (36%) say they sometimes or often talk with friends about religion.

Not surprisingly, religious teens are particularly likely to engage in these kinds of discussions. Almost half (45%) of religiously affiliated teens report that they regularly (that is, “sometimes” or “often”) talk to their friends about religion. Conversely, only 17% of unaffiliated teens at least sometimes talk to their friends about religion.

But there also are differences among religiously affiliated teens. A majority of evangelical Protestant teens (58%) regularly talk to their friends about religion, compared with about four-in-ten mainline Protestant teens (39%) and roughly a third of Catholics (35%).

In addition to religious affiliation, gender and region also are related factors. Four-in-ten girls (41%) report sometimes or often talking to their friends about religion; just three-in-ten boys (31%) say the same.

Adolescents in the South are particularly likely to talk to their friends about religion. About four-in-ten Southern teens (41%) report doing so at least sometimes, while smaller shares in the West (31%) and Northeast (29%) say the same.

There are fewer differences across age, grade, and race and ethnicity in how frequently teens report talking with friends about religion.