People in Central and Eastern Europe generally see churches and other religious institutions – now back in the public sphere after being largely hidden during the Soviet era – as making positive contributions to society. Respondents in the region tend to say that churches play beneficial roles in their countries by strengthening social bonds and helping the poor.

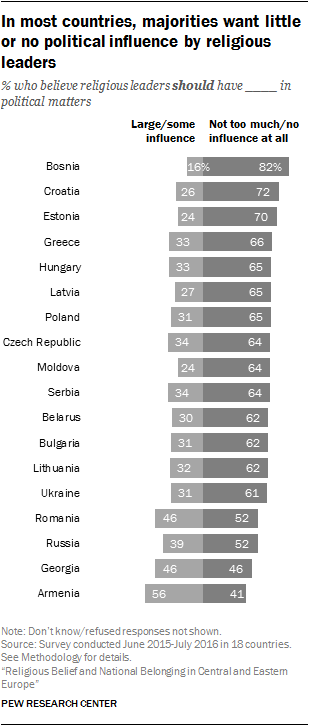

At the same time, considerable shares in many countries – including majorities in some – also say religious institutions are overly focused on money and power, excessively focused on rules and too involved with politics. Indeed, majorities in most countries surveyed prefer that religion be kept separate from government policies and say religious leaders should have little or no influence in political matters (even if they perceive these same religious leaders as having at least some political influence).

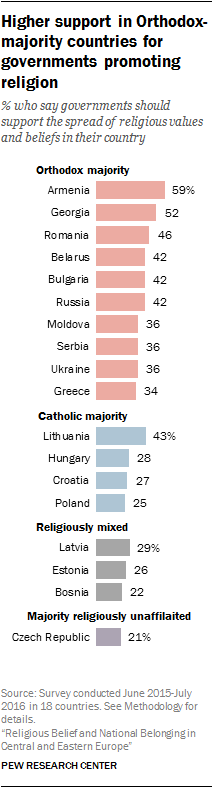

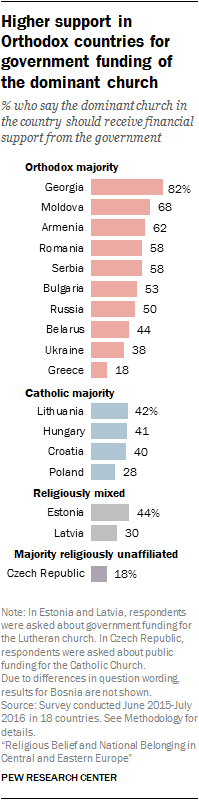

Adults in Orthodox-majority countries are more comfortable with state support for religion than are people in Catholic-majority or religiously mixed nations surveyed. In Georgia and Armenia, for example, the prevailing view is that government should promote religious beliefs and values.

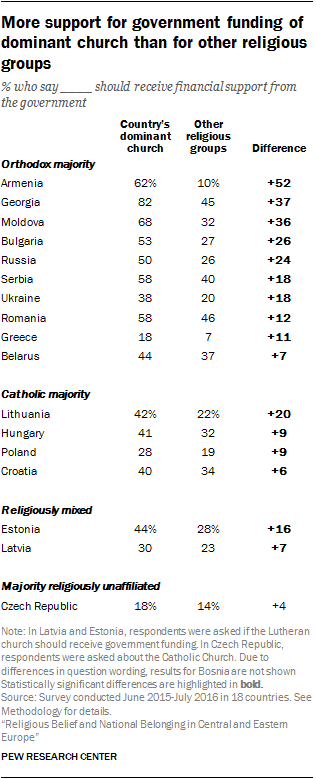

People in Orthodox countries also are more likely than others in the region to favor state funding for the main religious denomination in their country – in many cases the national Orthodox church, such as the Serbian Orthodox Church. But fewer than half in most cases support government funding for other religious groups or say Muslim religious organizations should be permitted to receive foreign funding.

Views of religious institutions in the region more positive than negative – but not everywhere

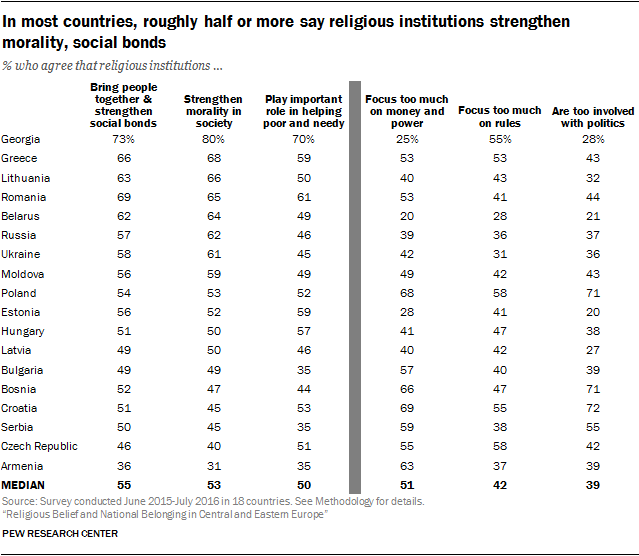

To gauge views of religious institutions in general, the survey asked respondents whether they agree or disagree with a series of six statements – three that proposed potential positive attributes of religious institutions and three that offered negative ones. On balance, adults across the region are more likely to agree with the positive statements. In most of the countries surveyed, roughly half or more say religious institutions strengthen morality in society, bring people together and strengthen social bonds, and play an important role helping the poor and needy.

But considerable shares – and in some cases majorities – across the region also say religious institutions focus too much on money and power, focus too much on rules or are overly involved with politics. In Poland, for example, majorities say all three of these things are the case, with on balance, higher shares of Poles agreeing with these negative views of religious institutions than positive views. In fact, Poles are about as likely as or more likely than Czechs to take negative views of religious institutions, even though the vast majority of Poles are Catholic, while most Czechs are religiously unaffiliated. And in Bosnia and Croatia, the views that religious institutions are too concerned with money and power (66% and 69%, respectively) and too involved with politics (71% and 72%) are far more common than the perceptions that they strengthen morality in society, strengthen social bonds or help the poor.

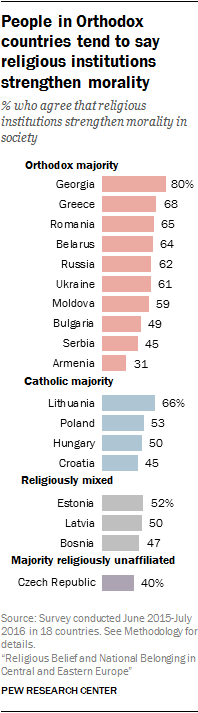

The view that religious institutions strengthen morality in society is more common in Orthodox-majority countries than elsewhere in the region. Majorities say this in seven of the 10 Orthodox countries surveyed, including the vast majority in Georgia (80%).

By comparison, this position is less common in Catholic-majority countries.

Adults who attend religious services at least weekly and those who say religion is at least somewhat important in their lives are more likely than those who are less religiously observant to have positive views of religious institutions.

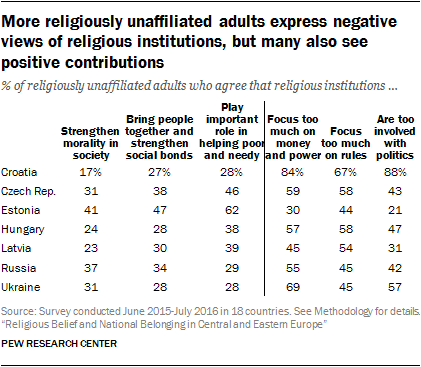

Religiously unaffiliated adults, on the other hand, are more likely to express negative views of religious institutions. In all seven countries with adequate sample sizes of unaffiliated adults, fewer than half say religious institutions strengthen morality in society, while considerably more say religious institutions are overly concerned with money, power and rules.

And yet, substantial proportions of religiously unaffiliated adults (sometimes referred to as religious “nones”) express some positive views of religious institutions. For example, in Estonia, most religious “nones” (62%) say religious institutions play an important role in helping the poor and needy. And roughly a quarter or more of unaffiliated adults in all seven countries say religious institutions strengthen social bonds.

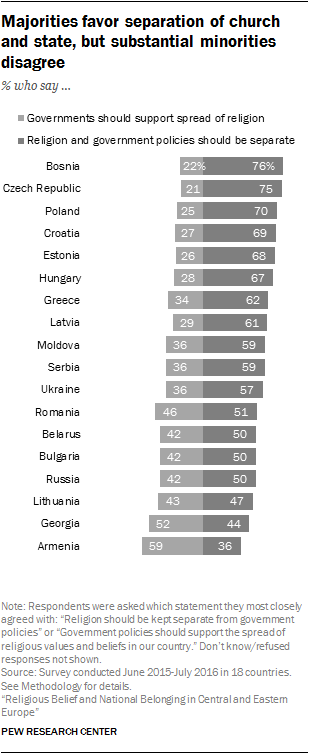

Most say religion should be kept separate from government policies

In most of the countries surveyed, majorities or pluralities say “religion should be kept separate from government policies,” rather than taking the opposing view that “government policies should support the spread of religious values and beliefs.” Sentiment favoring the separation of religion and government is strongest in Bosnia, a religiously mixed country that endured a war in the 1990s fought along religious and ethnic lines, and the Czech Republic, which has a religiously unaffiliated majority.

Still, in every country surveyed, roughly one-in-five or more respondents say governments should promote religious values, including a majority in Armenia (59%) and roughly half in Georgia (52%).

People in Orthodox-majority countries are particularly likely to favor government support for the spread of religious values. About a third or more favor this in every Orthodox-majority country surveyed. By contrast, in Catholic-majority, religiously unaffiliated or religiously mixed countries, support for government promotion of religious values and beliefs generally is lower.

Religiously unaffiliated respondents and those with low levels of religious observance are more likely to favor separation of religion and government. People with a college education also are especially likely to take this position.

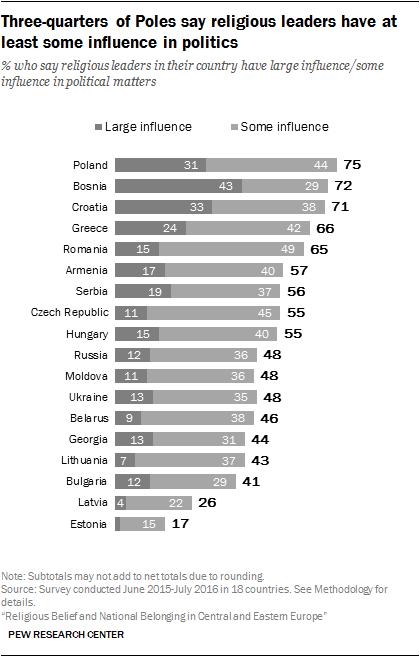

Many see religious leaders as having at least some influence in politics, but majorities say this should not be the case

Respondents were asked about the role currently played by religious leaders in political matters: Do they have a large influence, some influence, not too much influence or no influence at all? Majorities or pluralities of adults in most countries surveyed say these leaders have at least some influence in the politics of their country. This includes roughly three-in-ten or more in Bosnia, Croatia and Poland who say religious leaders in their country have a large influence in political matters.

Even in the majority-unaffiliated Czech Republic, most people say religious leaders have at least some influence on politics.

Two Catholic-majority countries, Poland and Croatia, have among the highest shares of people saying religious leaders have at least some influence on politics in their country (75% and 71%, respectively).

A parallel question, in which respondents were asked how much influence religious leaders should have in politics (and were given the same four response options), finds that in most of the countries where religious leaders are widely seen as having political influence, majorities oppose that influence.

In Poland, Bosnia, Croatia and Greece, where about two-thirds or more say religious leaders are influential in politics, roughly two-thirds or more would prefer for these leaders to have either “not too much influence” in political matters or “no influence at all.” For example, in Bosnia, 72% say religious leaders have at least some influence in politics in their country, while 82% say they should not have so much influence.

Overall, majorities in 14 of the 18 countries surveyed believe religious leaders should have little or no influence in political affairs. Armenia is the only country where most respondents (56%) say religious leaders should have either a “large influence” (21%) or “some influence” (35%) in politics.

Religiously observant adults (that is, those who say religion is very important in their lives, pray daily or attend religious services weekly) are more likely than others to say religious leaders should have an influence on political matters. And overall, religiously unaffiliated respondents are less likely than Muslims, Catholics or Orthodox Christians to take this position.

Substantial support for government funding for a country’s main church or religious institution

In each country, respondents were asked whether the dominant church or religious institution in their country should receive financial support from the government. For instance, Russians were asked whether the Russian Orthodox Church should receive public funding, while Hungarians were asked the same about the Roman Catholic Church in Hungary. (In Bosnia, respondents were asked about public funding for regional churches; results are not analyzed here because the question was not directly comparable to what was asked in other countries. See topline for full results.)

Half or more of adults in seven of the 17 countries analyzed, and substantial proportions of adults elsewhere, say the dominant church in their country should receive financial support from the government.

Adults in Orthodox-majority countries are particularly inclined to express support for this type of government funding. In most Orthodox countries, higher shares say the government should support the national Orthodox church than say it should not. For example, in Russia, 50% support public funding of the Russian Orthodox Church, compared with 38% who oppose it.

On the other hand, in the Catholic-majority countries of Lithuania, Hungary, Croatia and Poland, fewer than half of respondents say the Catholic Church should receive public funds.

Across the region, those who say religion is at least somewhat important in their lives are significantly more likely than others to favor public funding of their country’s dominant church. A similar pattern emerges when comparing those who pray daily or attend church weekly with those who do so less often.

Women are more likely than men to say that churches should receive financial support from the government, and respondents without a college degree are more likely than college graduates to say this.

Less support for public funding of other religious groups

Should religious groups other than a country’s dominant denomination receive funding from the government? In nearly every country surveyed, fewer people favor public funding for other religious groups than favor government financial support for the dominant church.

In Orthodox-majority countries, the share of adults who support public funding of other religious groups tends to be considerably lower than the share supporting government funding of the national Orthodox church. In Russia, for example, 50% say they support public funding for the Russian Orthodox Church, compared with 26% who favor public funding for other religious organizations.

By comparison, in most other countries surveyed, there is a smaller gap between the shares of people who support government funding for the Catholic or Lutheran churches and those who favor public funding for other religious groups.

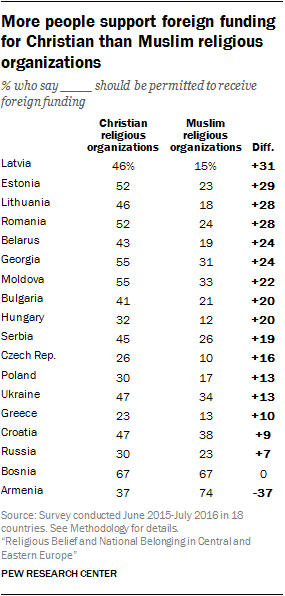

Overall, low support for foreign funding of religious groups – especially Muslims

In most countries, fewer than half of respondents say foreign funding of religious organizations – whether Muslim or Christian – should be permitted. But more people in the predominantly Christian region say Christian religious organizations in their country should be permitted to receive foreign funding than say the same about Muslim organizations.

Muslims in the region are more likely than others to say foreign funding for Muslim religious organizations should be permitted. That said, in the four countries where sample sizes of Muslims are large enough for analysis, Muslims are about as likely to support allowing foreign funds for Christian religious organizations as they are for Muslim ones.

Armenia is the one country surveyed where the share supporting foreign funding for Muslim organizations far exceeds the share that supports foreign funding for Christian organizations (74% vs. 37%). One theory explaining Armenians’ broad support for allowing Muslim organizations to receive foreign funding is that many Armenians know about (and accept) Iranian funding of the recent restoration of the Blue Mosque of Yerevan. Armenia and neighboring Iran have close political and cultural ties, and the mosque is primarily used by Iranians visiting or living in Yerevan, Armenia’s capital.28