This report focuses on how immigrant members of the ethnically diverse Asian population navigate through challenges related to language and culture in the United States. The analysis is based on a Pew Research Center analysis of the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2021 American Community Survey and 49 focus groups of participants from across the U.S. that we conducted virtually in the fall of 2021 in 17 non-English languages. This is part of a broader focus group project that explored the identity, economic mobility, representation, and experiences of immigration and discrimination among the Asian population in the United States.

The discussions in these groups may or may not resonate with other Asians living in the United States, as participants were recounting their personal experiences. All quotes in this report were translated from 17 non-English languages into English and have been lightly edited for readability, and punctuation.

By including participants of different languages, immigration or refugee experiences, educational backgrounds, and income levels, this focus group study aimed to capture, in people’s own words, what it means to be Asian in America. More information about the groups and analysis can be found in this methodology page.

The terms “Asian” and “Asian American” are used interchangeably throughout this report to refer to U.S. adults who self-identify as Asian, either alone or in combination with other races or Hispanic identity.

“The United States” and “the U.S.” are used interchangeably with “America” for variations in the writing.

U.S. born refers to people born in the 50 U.S. states or the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico or other U.S. territories.

Immigrant refers to people who were not U.S. citizens at birth – in other words, those born outside the U.S., Puerto Rico or other U.S. territories to parents who were not U.S. citizens. The terms “immigrant” and “foreign born” are used interchangeably in this report.

New immigrant arrivals to the United States face many challenges and obstacles when navigating their daily lives. For Asian immigrants, these include language and cultural obstacles that impact those who arrive with little to no proficiency in English. But navigating life in America also impacts English-speaking immigrants as they adjust to life in a new country with its own unique linguistic and cultural quirks.

A little over half of Asian Americans (54%) were born outside the United States, including about seven-in-ten Asian American adults (68%). While many Asian immigrants arrived in the United States in recent years, a majority arrived in the U.S. over 10 years ago. The story of Asian immigration to the U.S. is over a century old, and today’s Asian immigrants arrived in the country at different times and through different pathways. They also trace their roots, culture and language to more than 20 countries in Asia, including the Indian subcontinent.

In 2021, Pew Research Center conducted 49 focus groups with Asian immigrants to understand the challenges they faced, if any, after arriving in the country. The focus groups consisted of 18 distinct Asian origins and were conducted in 17 Asian languages. (For more, see the methodology.)

Across the focus groups, daily challenges related to speaking English emerged as a common theme. These include experiences getting medical care, accessing government services, learning in school and finding employment along with speaking English and understanding U.S. culture. Participants also shared frustration, stress and at times sadness because of the cultural and language barriers they encountered. Some participants also told us about their challenges learning English, as well as the times they received support from others to deal with or overcome these language barriers.

Among Asian immigrants, recent arrivals report lower English proficiency levels than long-term residents

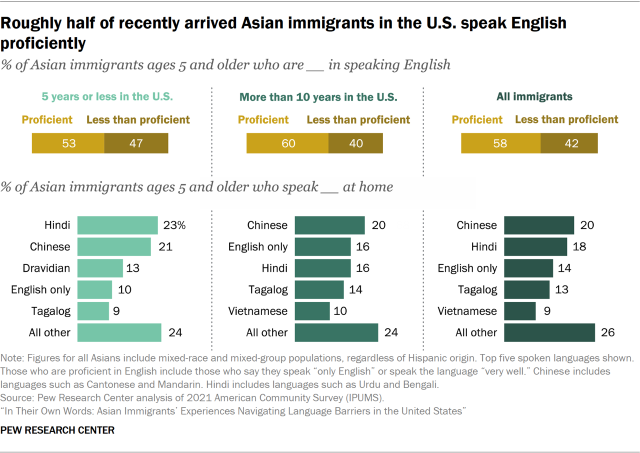

Focus group findings about learning English and challenges navigating life in the U.S. are reflected in government data about English proficiency among Asian immigrants. For example, about half (53%) of Asian immigrants ages 5 and older who have been in the U.S. for five years or less say they speak English proficiently, according to a Pew Research Center analysis of Census Bureau data. By contrast, 60% of Asian immigrants who have been in the U.S. for more than a decade say they speak English proficiently, a higher share than recent arrivals.

Among Asian Americans ages 5 and older, 58% of immigrants speak English proficiently, compared with nearly all of the U.S. born who say the same (94%).

There is language diversity among Asian immigrants living in the U.S. The vast majority (86%) of Asian immigrants 5 and older say they speak a language other than English at home, while 14% say they speak only English in their homes. The most spoken non-English language among Asian immigrants is Chinese, including Mandarin and Cantonese (20%). Hindi (18%) is the second most commonly spoken non-English language among Asian immigrants (this figure includes Urdu, Bengali and other Indo-Iranian and Indo-European languages), followed by Tagalog and other Filipino languages (13%) and Vietnamese (9%). This reflects the languages of the four largest Asian origin groups (Chinese, Indian, Filipino and Vietnamese) living in the U.S. But overall, many other languages are spoken at home by Asian immigrants.

The following chapters explore three broad themes from the focus group discussions: the challenges Asian immigrants have faced in navigating daily life and communicating in English; tools and strategies they used to learn the language; and types of help they received from others in adapting to English-speaking settings. The experiences discussed may not resonate with all Asian U.S. immigrants, but the study sought to capture a wide range of views by including participants of different languages, immigration or refugee experiences, educational backgrounds and income levels.