This is the fourth of four detailed sections in a report on Americans’ views about the role of journalists in the digital age. The report also includes an overview of the key findings.

This section includes several questions we asked Americans (in both a survey and focus groups) about how acceptable it is for journalists to advocate for the communities they cover or express their own personal views and beliefs – both in the context of their work and in public social media posts. With these questions, we hoped to speak to an ongoing debate about the traditional concepts of objectivity and neutrality in journalism.

We also asked about how people think journalists should handle some of the decisions they encounter in their day-to-day job.

Attitudes toward journalists advocating for communities they cover and expressing personal views

Americans express mixed views about the role of advocacy in journalists’ work and social media presence.

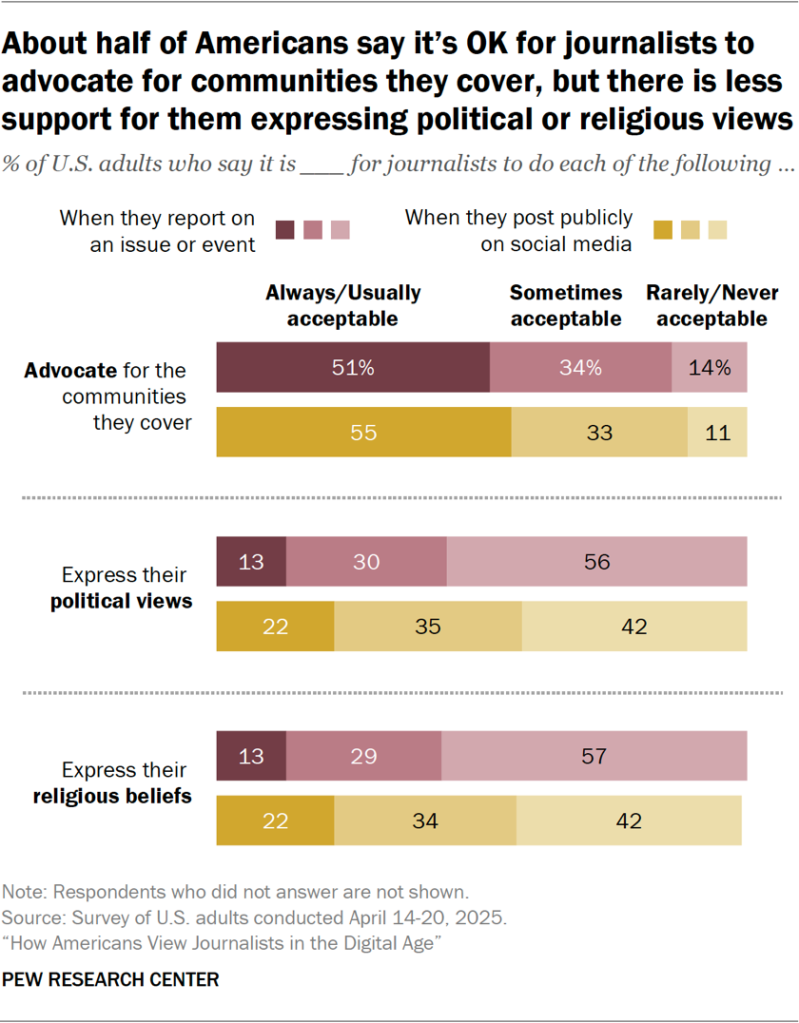

About half of U.S. adults (51%) say that when journalists are reporting on an issue or event, it is always or usually acceptable for them to advocate for the communities they cover. About a third (34%) say this is sometimes acceptable, while 14% say it is rarely or never acceptable.

People express similar views when asked if it’s acceptable for journalists to advocate for communities they cover when they post publicly on social media.

However, Americans are far less likely to find it acceptable for journalists to express personal views when they are reporting on issues or events.

Equal shares of U.S. adults – 13% each – say it’s always or usually acceptable for journalists to express their political views or religious beliefs when reporting on issues or events. Majorities of Americans say this is rarely or never acceptable (56% and 57%, respectively).

People are somewhat more accepting of journalists sharing political or religious views publicly on social media: 22% think it is always or usually acceptable for journalists to do this in both cases, and about a third (35% and 34%, respectively) say it’s sometimes acceptable. But in each case, the most common view is that it’s rarely or never acceptable for journalists to post these kinds of views publicly on social media.

When asked about journalists advocating for the communities they’re covering or for social or political change, focus group participants expressed mixed views. Some took a hard line against advocacy: As one man in his 30s said, “If you’re a journalist, let’s stick to journalism. And if you want to be an influencer or a social change warrior or whatever, just stick to that … when you expect them to be a journalist, you expect them to be neutral.”

Others felt advocacy could be acceptable in some cases, as long as journalists are, first and foremost, finding and reporting the facts. As one woman in her 50s said, journalists “should remain neutral until they get all the facts in.” A woman in her 20s said about journalists sharing opinions, “I think good, have it, express it, but just you can’t make the news your opinion. You still have to convey the facts and then explain why your opinion is what it is. … I just think if it’s too mixed, you erase the news and hide it behind a position.”

Some of those who are open to advocacy by journalists described it as serving communities’ needs or speaking for those who don’t have power. One man in his 4os said, “I think the stories that journalists tell are supposed to be reflective of the people that consume the news, so if they’re advocating for certain communities that watch and tune in, look for that type of content, I think it makes sense.” One woman in her 50s said advocacy by journalists can start broader conversations in society, adding, “The ultimate goal, I guess, in reporting is to make our society the best it can be. Or that’s what it should be.”

Some also suggested advocacy is more acceptable in particular types of journalistic work, such as investigative reporting, or when discussing topics they see as “nonpartisan.” One woman in her 20s said, “If it’s something everyone can agree on, like a natural disaster or a mass shooting … there’s a same kind of opinion that it’s sad or those victims should get help.”

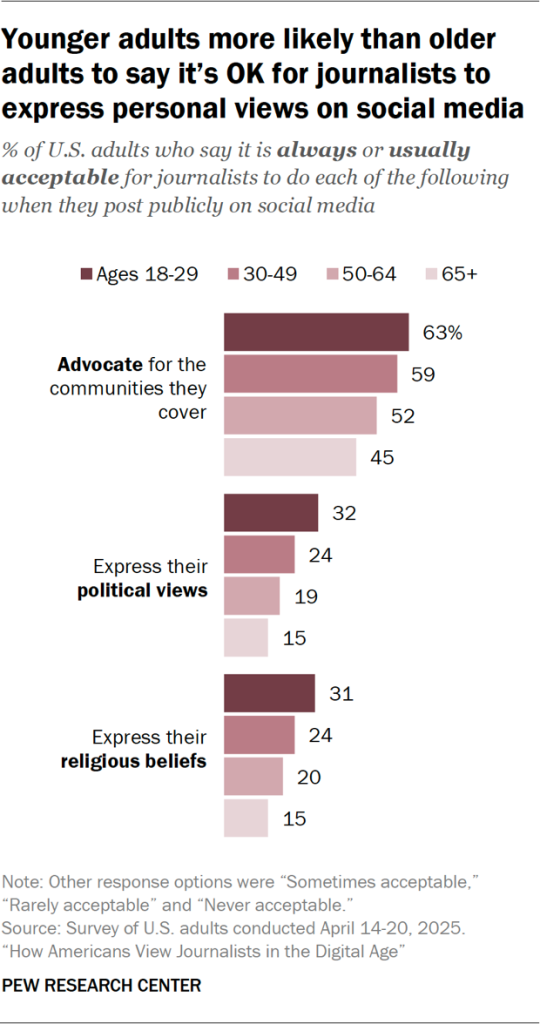

Overall, the survey found that younger adults are more likely than older people to say it is always or usually acceptable for journalists to advocate for communities they cover and express their views – but these age differences are particularly stark when it comes to social media:

- 63% of Americans ages 18 to 29 say it’s always or usually acceptable for journalists to advocate for the communities they cover when posting publicly on social media, compared with 45% of those 65 and older.

- About three-in-ten adults under 30 think it’s generally acceptable for journalists to express their political views (32%) or religious beliefs (31%) publicly on social media, roughly double the share of adults 65 and older who say the same (15% on both).

When it comes to political party, Democrats and independents who lean Democratic are more likely than Republicans and Republican leaners to say it is always or usually acceptable for journalists to advocate for communities they cover, both in reporting and on social media.

At the same time, Republicans are slightly more likely than Democrats to see it as acceptable for journalists to express their religious beliefs. (Republicans also tend to be more religious than Democrats by a variety of measures.)

Do Americans think journalists can separate their personal views from their reporting?

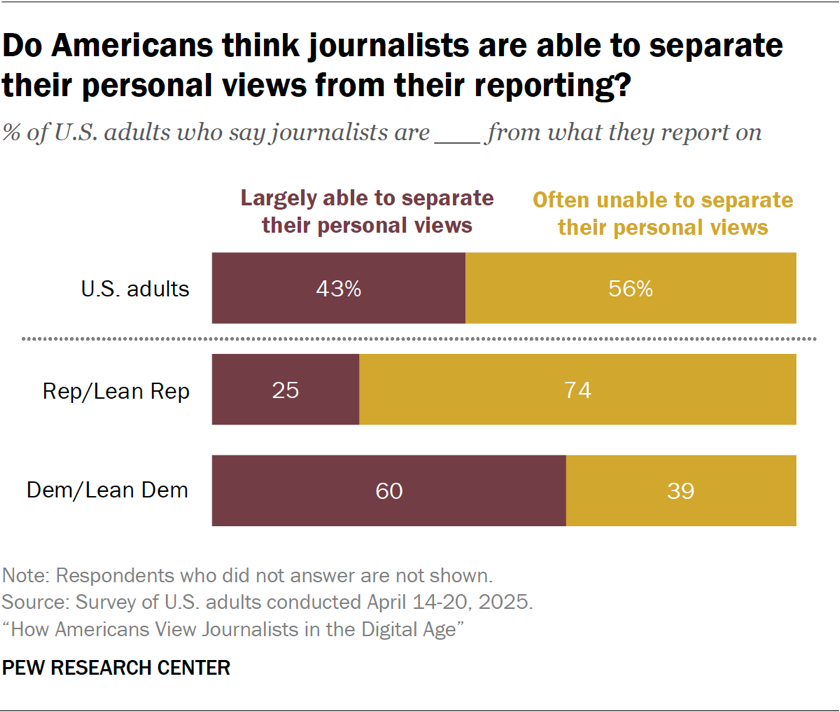

While many Americans say it is rarely or never acceptable for journalists to express personal views when reporting, people also commonly express skepticism about whether it’s even possible for journalists to separate their views from their reporting.

More Americans think journalists are often unable to separate their personal views from what they report on (56%) than think they are largely able to do so (43%).

These perceptions differ drastically by political party, with Republicans far more likely than Democrats to say journalists are often unable to separate their personal views from what they report on (74% vs. 39%).

What should journalists share or cover?

The survey also asked Americans how they think journalists should cover news stories in a few specific ways. One oft-debated question is whether journalists should always strive to give equal coverage to all sides of an issue, sometimes negatively described as “bothsidesism.”

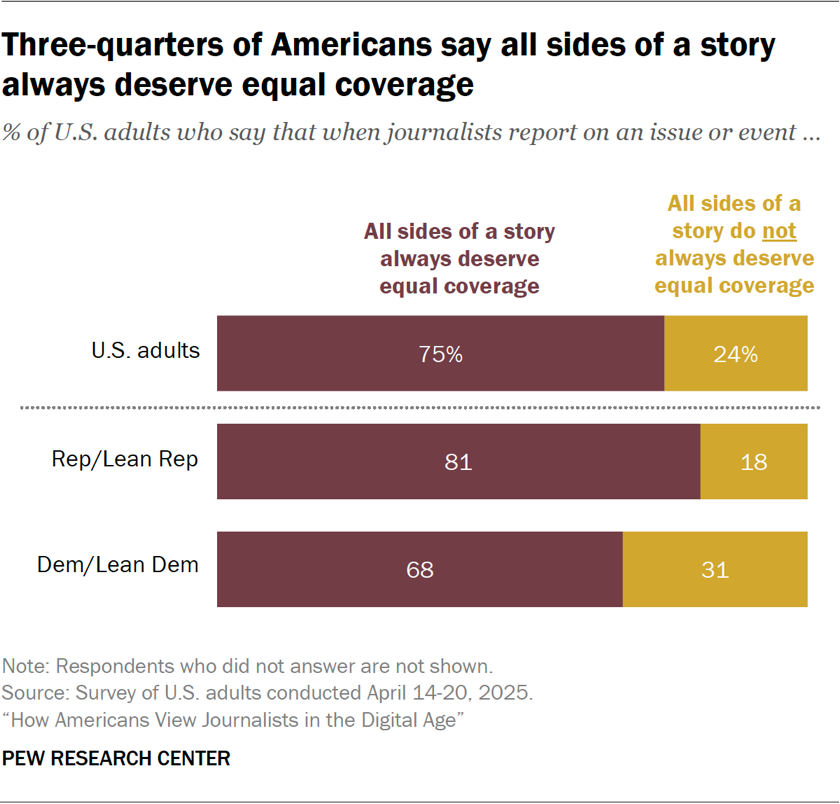

Three-quarters of Americans say that when journalists report on an issue or event, all sides of a story always deserve equal coverage.

Meanwhile, about a quarter (24%) say all sides of a story do not always deserve equal coverage. U.S. journalists are much more likely than the public to express this perspective, according to 2022 Pew Research Center surveys.

Among U.S. adults overall, majorities of both major political parties say that all sides of a story always deserve equal coverage, although Republicans are modestly more likely than Democrats to take this position (81% vs. 68%).

These findings were echoed widely across our focus groups. When asked what a journalist’s job is, participants said journalists should strive to share multiple perspectives and a balanced set of facts. As one man in his 60s explained, journalists should “look at different sides of issues and bring context to things that we might need to know about. But a journalist, the way that I think classically is defined, is not someone who necessarily gives their particular opinion …. But they bring in all the facts, as opposed to the ones [that] support what they might personally believe.”

One man in his 30s said a journalist’s job is to “present the facts rather than necessarily their own views. But if they are going to share opinions, making sure that it’s sort of balanced, they’re showing multiple perspectives, multiple viewpoints and kind of allowing the general public to make their own decisions.”

Most Americans also agree on how journalists should cover false statements by public figures. If a public figure says something that is false or inaccurate, most U.S. adults (82%) believe journalists should report on the statement, while clarifying that it is false or inaccurate.

Small shares think journalists should not report on it at all (9%) or that they should report on the statement without clarifying that it is false or inaccurate (7%).

Supporters of both political parties overwhelmingly agree on this. Most Democrats (87%) and Republicans (79%), including those who lean toward each party, say journalists should report on the statement while clarifying that it is false.

Although small shares of both groups say this, Republicans are slightly more likely than Democrats to say journalists should report on false statements without clarifying that they are false (10% vs. 5%).

The importance of transparency

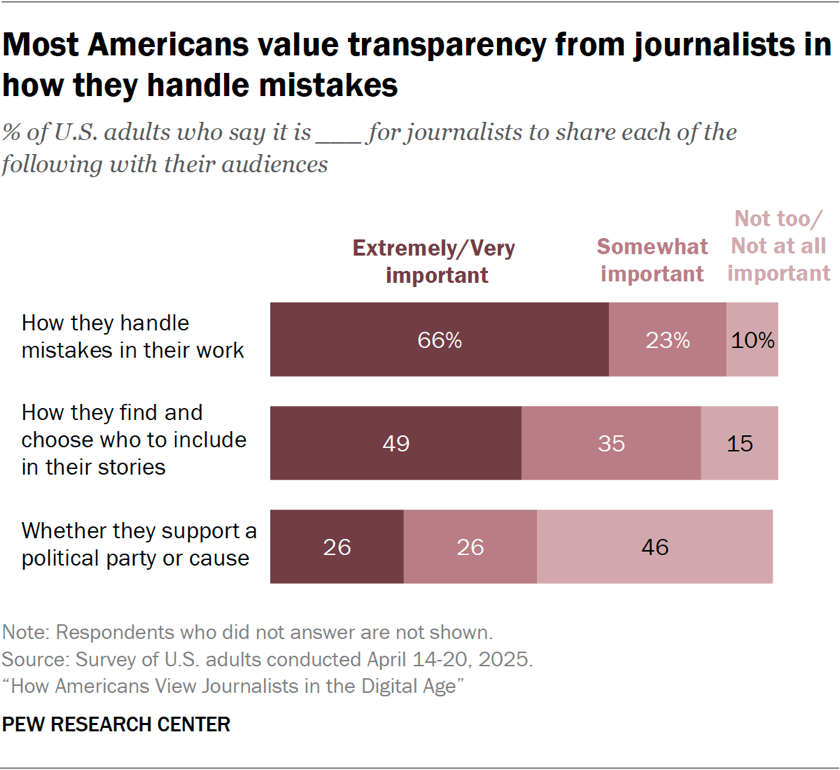

Americans are more likely to value transparency from journalists in certain aspects of their work than others.

About two-thirds of U.S. adults (66%) say it is extremely or very important for journalists to share with their audiences how they handle mistakes in their work.

Meanwhile, about half of Americans (49%) think it’s highly important for journalists to share how they find and choose who to include in their stories. A much smaller share (26%) say they think it’s highly important for journalists to tell their audiences whether they support a political party or cause.

When discussing transparency, focus group participants revealed one of the inherent contradictions at play when it comes to how journalists handle mistakes in their work. On the one hand, many said that journalists being transparent about mistakes increased, or would increase, their trust in that source. Participants often discussed the fact that everyone makes mistakes, and journalists owning up to it “makes them human.”

At the same time, they recognized that admitting to mistakes can jeopardize journalists’ credibility. In one focus group, a man in his 60s said, “It seems like people are afraid nowadays to share any mistakes. It’s like if they make a mistake, they’re terrible, you know? And that’s sad because we should realize that we all make mistakes.” A man in his 40s replied, “The bad side of that is, if a journalist shares too many mistakes, they get labeled as misinformation and fake news. So they have an incentive to not admit their mistakes.”

Some participants also shared specific ways in which they believe journalists miss the mark on transparency. One man in his 60s described how newspapers will “put something on the front page that’s not right, and then [the retraction of] the mistake will be on page 820 or something.”

Democrats and Republicans largely agree on these aspects of transparency in the survey; there are no major differences in how supporters of both parties answer these questions.