Introduction

[2, 12-14]

[20, 21]

Some fear that internet activities in the home may substitute for participation in neighborhood and public spaces. Time spent online may replace time that would otherwise be spent socializing with ties and in places outside the home. Others suggest that the internet provides new opportunities for interaction with diverse social ties. The Pew Internet survey examined these issues: Is the use of ICTs associated with less participation in neighborhood and public life? And, in turn, does internet and mobile phone use constrain the diversity of people’s social networks?

Are internet users less likely to participate in the local community?

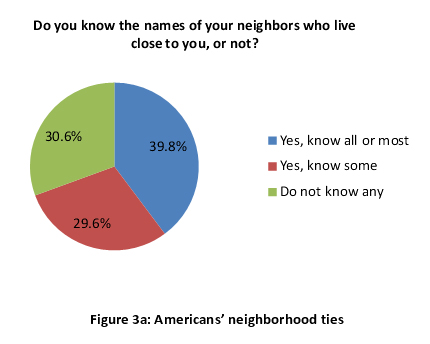

Most people know at least some of their neighbors.

As part of the survey, people were asked if they “know the names” of their neighbors who live close to them. Some 40% of Americans reported that they know all or most of their nearest neighbors. Another 30% reported that they know at least some of their neighbors. Some 31% of people said that they do not know any of their neighbors.

We expected that many of those who reported no connection with neighbors are disconnected because of their stage in the life cycle and not because they are socially isolated (for example, young adults who have yet put down roots in a community). Regression analysis, reported in Appendix D as Table 11, confirms that where one lives, how old he/she is, and their use of ICTs all matter for connections to local community.

[23]

- Apartment dwellers are 60% less likely than home dwellers to know at least some of their neighbors.

- Those who are married or cohabitating are 31% more likely to know their neighbors.

- The likelihood of knowing at least some neighbors increases 3% for every year of age.

Additional demographic factors also matter.

- Residential stability, the longer one lives in any one place increases the odds of knowing neighbors; 6% per year.

- The odds that women know at least some neighbors are 41% higher than for men.

- Those with larger, core networks are more likely to know neighbors. The odds are 19% higher per core tie in their network.

- The odds of knowing at least some neighbors are 50% lower for African Americans and 43% less for those of other races, in comparison to white Americans.

With the exception of those who use social networking services, internet users are no more or less likely to know at least some of their neighbors.

Those who use a mobile phone and most internet users are no more or less likely than non-tech users to know neighbors. However, this is not the case for those internet users who use social networking services.

- Users of social networking services are 30% less likely to know their neighbors.

Example: There is a 82% probability that an average 30-year-old, white, female, who is married or cohabitating, and does not live in an apartment building, knows at least some of her neighbors. If she uses social networking services, the probability is lower, at 77%.12

The majority of Americans talk with their neighbors on a regular bases.

[24, 25]

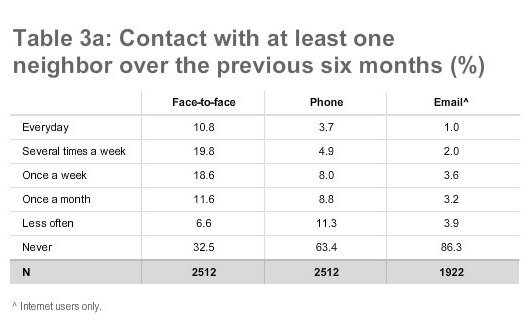

Pew Internet participants were asked how often they talked, phoned, and emailed those neighbors whom they know by name. Findings reveal that 61% of Americans talk face-to-face with neighbors at least once a month. In addition, 25% talk to their neighbors on the phone at least on a monthly basis, and 10% of internet users email with neighbors at least once per month.

Internet and mobile phone use is not related to the likelihood of having face-to-face contact with neighbors.

Regression analysis, reported as Table 12 in Appendix D, confirms that internet use does not substitute for in-person contact at the neighborhood level.

- Mobile phone use, internet use, frequency of use, or participating in social networking services, blogging, photo sharing, or instant messaging, was found to have no relationship with the likelihood of face-to-face contact with neighbors.

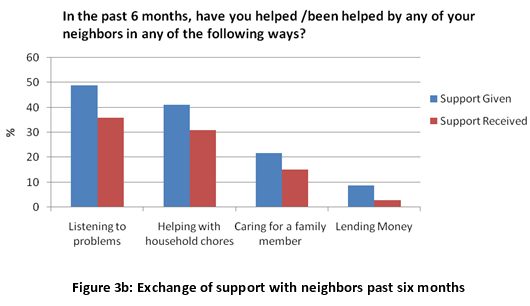

Neighbors remain an important source of companionship and are available for small services, borrowing small sums of money, and care for family members.

[2]

In the Pew Internet survey, 49% of Americans had helped their neighbors over the previous six months by listening to their problems; 41% helped with household chores, shopping, repairs, house-sat, or loaned tools or supplies; 22% cared for a member of a neighbor’s family, either a child or an adult; and 9% loaned a neighbor money.

Many more people reported giving than receiving help from neighbors. Only 36% reported that a neighbor had listened to their problems, 31% received help with chores or borrowed tools or supplies, 15% were cared for or had a family member cared for by a neighbor, and 3% borrowed money.

Although the exchange of support at the neighborhood level is extensive, there is a modest lack of reciprocity in neighbor exchanges (or possibly a heightened awareness/memory of giving and a reduced awareness/memory of receiving support).

The internet makes some forms of social support more accessible outside of the neighborhood setting. As a result, some internet users are less likely to rely on neighbors for support.

Regression analyses, reported as Table 13 and Table 14 in Appendix D, explore the relationship between ICT use and various forms of social support. The findings include:

- Users of social networking services are 26% less likely to have used neighbors as a source of companionship.

- With the exception of those who use instant messaging, internet users are 26% less likely to have received small services (e.g., household chores, shopping, repairs, house-sat, lent tools or supplies) from neighbors.

- Internet users are 40% less likely to have been cared for, or had a member of their family cared for, by a neighbor. And, users of social networking services are 39% less likely than other internet users, or 64% less likely than those who do not use the internet, to have received family care from a neighbor.

- Internet users who are frequent users at work are 57% less likely to borrow money from neighbors.

- The only internet activities associated with receiving higher levels of neighborhood support are sharing digital photos online, which is associated with a 52% higher likelihood of receiving companionship, and instant messaging, with odds that are 32% higher of receiving small services.

Variation in what people do online is related to the likelihood of giving support to neighbors.

- Those who share digital photos online are 44% more likely to give companionship to neighbors.

- Bloggers are 79% more likely, and those who upload photos to share online are 40% more likely to provide small services to neighbors.

- Internet users are 40% less likely to provide family care to neighbors. However, this relationship is moderated, or even reversed, depending on a person’s online activities. Frequent internet users at home are 46% more likely than other internet users, bloggers are 84% more likely than other internet users, and those who use instant messaging are 33% more likely than other internet users to provide family care to neighbors.

- With the exception of bloggers, who are as likely to lend money as anyone else, internet users are 48% less likely to lend money to neighbors.

It is unlikely that internet users need less family care or less help with household chores and repairs than do non-users. Instead, the internet may provide access to existing social network members in a way that substitutes for some of the small services and family care that people otherwise would have received from neighbors. This may be particularly true for users of social networking services, who receive companionship from other social ties and coordinate family care online, rather than in the neighborhood.

It is also likely that some of what we observed has less to do with the use of technology than it does with individual characteristics. For example, those who use the internet frequently at work likely represent an occupational class that has higher socioeconomic characteristics in general, making them less likely to borrow money from neighbors because of their economic standing, rather than a function of their technological use. Similarly, those who upload photos to share online may represent particularly extroverted, hyper-social sharing types, who experience increased companionship as a result of their individual nature, not specifically as a result of their use of the internet.

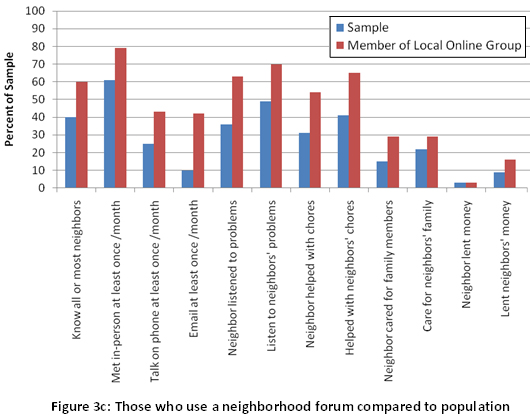

Connecting with neighbors online is associated with high social cohesion and a network of support.

A small number of Americans – 4% (N=103) – reported that they belonged to a neighborhood email list or internet discussion forum for their neighborhood (e.g., i-neighbors.org). Although this suggests that only a small fraction of neighborhoods are using the internet for local communication and information sharing, those who do adopt this technology benefit from high levels of neighborhood engagement.

- 60% of those who use a neighborhood discussion forum know “all or most” of their neighbors, compared to 40% other Americans.

- 79% who use a neighborhood discussion forum talk with neighbors in person at least once a month, compared to 61% of the general population.

- 43% on a neighborhood discussion forum talk to neighbors on the telephone at least once a month, compared to the average of 25%.

- 42% of those who belong to a neighborhood discussion forum email neighbors at least monthly, compared to 10% of general internet users.

- 70% on a neighborhood discussion forum listened to a neighbor’s problems in the previous six months, and 63% received similar support from neighbors, in comparison with 49% who gave and 36% who received this support in the general population.

- 65% who belong to a neighborhood discussion forum helped a neighbor with household chores or loaned a household item in the previous six months, 54% received this support compared to the average 41% who gave and 31% who received.

- 29% who use a neighborhood discussion forum cared for a neighbor in the previous six months, and 29% were cared for by a neighbor, compared to the average American, 22% of whom gave care and 15% of whom received care from neighbors.

- 16% of those on a neighborhood discussion forum loaned money to a neighbor in the previous six months, 3% borrowed, in comparison with the 9% who loaned and 3% who borrowed in the general population.

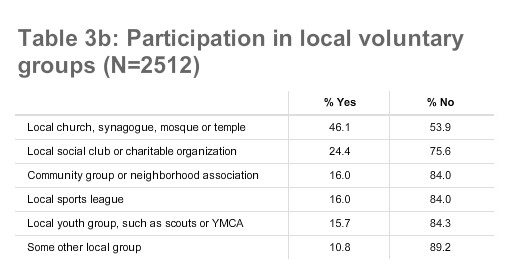

A majority of Americans belong to at least one local voluntary group.

In addition to participation in their immediate neighborhood, as part of the survey people were asked about participation in broader local voluntary groups. They were asked if they belong to or ever work with a “community group or neighborhood association that focuses on issues or problems in your community,” “a local sports league,” “a local youth group, such as scouts or the YMCA,” “a local church, synagogue, mosque or temple,” “a local social club or charitable organization,” or “some other local group” that had not already been mentioned. Results show that 65% of Americans belong to at least one local group.

Mobile phone users, bloggers, and frequent internet users at work are more likely to belong to a local group.

Regression analysis, reported in Appendix D as Table 15, confirms that participation in local groups varies, based on mobile phone and internet activity. We found no negative relationships between internet use and participation in local groups. Compared to other demographic factors associated with participation in local groups, such as education, the positive relationship between ICT use and local group membership is relatively strong.

- The odds of mobile phone users belonging to a local group are 72% higher than for those who do not own a mobile phone.

- Those who access the internet from work at least a few times per day are 46% more likely to belong to at least one local group.

- Bloggers are 72% more likely to belong to a local group.

The relationship between mobile phone use or blogging, independent of each other, on group membership is comparable to that of approximately four years of education. The relationship between frequent internet access from work and group membership is comparable to that of marriage or having children at home, all of which are associated with about 50% higher odds of local group involvement.

Example: An average person who is single, white, with no children has a 40% probability of belonging to at least one local voluntary group. If he/she owns a cell phone, the probability is higher, at 54%. If he/she also frequently uses the internet at work and blogs, the probability is 74%.

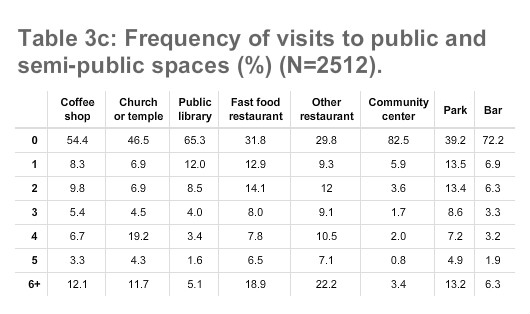

Most people spend time in a diverse number of places outside of the home and workplace.

[1, 7, 26-29]

Internet users and mobile phone users are more likely to use many public and semipublic spaces outside of the home and workplace.

Our findings from a series of regression analyses, reported as Table 16 and Table 17 in Appendix D, show that internet users are considerably more likely to visit a range of public and semipublic spaces, including parks, cafés, libraries, and restaurants, than are non-users of the internet.

- Internet users are 45% more likely to visit a café, 52% more likely to visit a library, 34% more likely to visit a fast food restaurant, 69% more likely to visit other restaurants, and 42% more likely to visit a public park.

Similarly, those who use a mobile phone are more likely to visit semipublic spaces than those who do not own a phone.

- Mobile phone users are 82% more likely to attend church, 81% more likely to visit a fast food restaurant, 63% more likely to visit other restaurants, and 56% more likely to visit a bar.

In addition, compared to other internet users, those who accessed the internet at work at least a few times per day were more likely to visit a range of public and semipublic spaces.

- Those who frequently access the internet at work are 49% more likely to go to a non-fastfood restaurant, 35% more likely to visit a community center, 21% more likely to visit a public park, and 71% more likely to go to a bar.

- However, frequent internet users at work were 26% less likely to visit a library.

We also found that:

- Those who contribute to a blog are 61% more likely to go to a public park than internet users who do not blog.

- Users of social networking websites are 40% more likely to visit a bar, but 36% less likely to visit a religious institution.

- Users of instant messaging are 21% less likely to visit a library than those who do not use IM.

Example: The probability that an average, single, 35-year-old man will visit a public park at least once a month is about 39%. However, if he is an internet user, the probability is higher; there is a 48% chance he will visit a park. If he also maintains a blog, there is a 60% chance he will visit.

As with other local community activities, the relationship between internet use and participation in public and semi-public spaces is likely a combination of self-selection and an outcome of internet use. For example, those who are in occupations that require frequent internet use in the workplace are probably more likely as a result of their socioeconomic status and stage in the lifecycle to visit a range of public and semipublic spaces. At the same time, the internet may also enable visits to public spaces through opportunities to coordinate rendezvous and search for new places to visit.

Internet use is a common activity in many kinds of public and semipublic spaces.

Although home and workplace are the dominant locations from which people access the internet, it has become increasingly possible for people to incorporate internet use into their everyday experiences in public spaces. Internet access in parks, cafés, and restaurants has been made possible through the proliferation of broadband wireless internet in the form of municipal and community wi-fi (e.g., NYC Wireless) and advanced mobile phone networks (e.g., 3G). We found that a significant proportion of people who visit public and semipublic spaces are online while in those spaces using a computer, mobile phone, or other devices:

- 36% of library patrons

- 18% of those in cafés or coffee shops

- 14% of those who visited a community center

- 11% of people who frequented a bar

- 8% of visitors to public parks and plazas

- 7% of customers at other restaurants

- 6% of customers at fast food restaurants

- 5% of people who visited church, synagogue, mosque or temple.

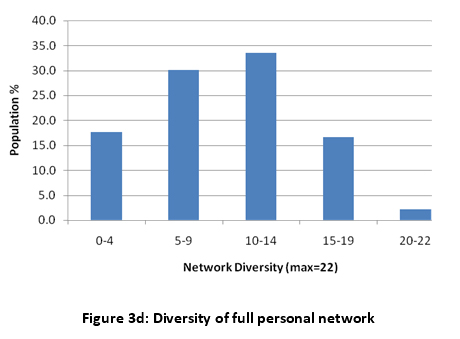

Are internet and mobile phone users’ networks more diverse?

[30]

[31]

Network diversity was measured as the number of different occupations in which a person has a social tie. We found that the mean person knows someone in 9.25 of the 22 occupations that were sampled.

Internet users, particularly those who are frequent users at work, and those who use social networking services, have broader social networks.

A regression analysis, Table 18 in Appendix D, confirms that compared to those who do not use the internet, those who use the internet have more diverse social networks. Higher levels of diversity associated with internet use are independent of participation in neighborhood social networks, voluntary associations, and public and semipublic spaces.

- Compared to non-users, those who use the internet tend to know at least one additional person in the occupational spectrum (0.71).

- Those who used the internet at work at least a few times per day know people, on average, in one and a half additional occupations (1.46).

- In addition, those who use a social networking service score on average .60 higher on the diversity scale.

Although no evidence was found that the use of ICTs reduces the overall diversity of social networks, the association between internet use and network diversity was relatively low compared to other demographic factors.

The single strongest predictor of diversity was age. A curvilinear relationship exists between age and network diversity, such that diversity increases steadily with age, although not as steadily for the elderly. After age, which accounts for time to build a diverse network, participation in diverse social settings (such as visiting public and semipublic spaces), participation in voluntary groups, and neighborhood involvement were most influential in predicting a diverse network. The size of core networks, presumably a means to access other networks, was also highly influential on network diversity. Although being a “frequent internet user at work” was also among the most influential variables in predicting diversity, this variable captures more about socioeconomic status and the participants’ occupational prestige than a causal relationship between internet use at work and the extent of a person’s overall social network. Heavy internet users at work have more diverse networks because of the type of work they do, not because of the internet.

Example: A white (non-Hispanic), married, 30-year-old male, who has a four-year university degree, an average core network (3 ties), visits an average number of public/semipublic spaces each month (12), knows at least some of his neighbors, and belongs to one voluntary group, on average knows people in seven of the twenty-two occupations on the scale (6.95). If he is an internet user, and uses a social networking service, on average he knows people in 8.26 occupations: a network that is 19% more diverse than someone who does not use the internet or own a mobile phone.