“Social Isolation in America: Changes in Core Discussion Networks”

In 2006 sociologists Miller McPherson, Lynn Smith-Lovin and Matthew Brashears delivered grim research findings: Americans’ core discussion networks, the network of people with whom people can discuss important matters, have shrunk and become less diverse over the past twenty years. They found that people depend more on a small network of home-centered kin and less on a larger network that includes ties from voluntary groups and neighborhoods. The authors argued that a large, unexpected social change was responsible for this trend and suggested it might be the rising popularity of new communication and information technologies such as the internet and mobile phone. Their study did not directly explore this possibility. Our current study was designed to probe: Is people’s use of the internet and cell phones tied to a reduction in the size and diversity of core discussion networks and social networks more broadly?

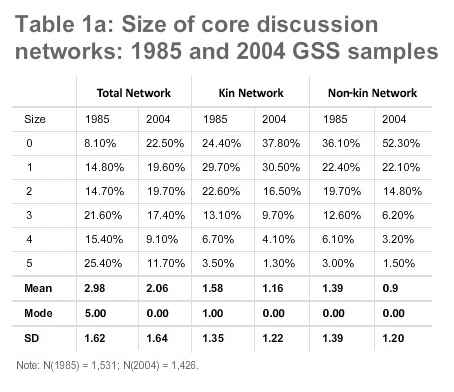

In their paper “Social Isolation in America: Changes in Core Discussion Networks” McPherson, Smith-Lovin and Brashears presented bleak findings from their analysis of the 2004 General Social Survey (GSS), a large biennial survey that explores social and economic trends. The authors found that, in comparison to the 1985 GSS, the data gathered in 2004 showed that the average number of confidants with whom Americans discuss important matters fell from 2.94 to 2.08. Furthermore, in 2004 a full 25% of Americans reported having no close confidants – almost a threefold increase since 1985.

McPherson et al. also argued that core discussion networks had not only shrunk but had become less diverse. A high proportion of those confidants lost between 1985 and 2004 were non-kin (not family members). That resulted in networks composed of a larger proportion of family members. In particular, spouses, partners, and parents were found to make up an increasingly large part of Americans’ core networks. The people Americans met through participation outside the home, such as in neighborhoods and voluntary organizations, had been disproportionately dropped from core networks.

[2]

If the number and diversity of those with whom people discuss important matters is threatened, so is the ability of individuals to be healthy, informed, and active participants in American democracy.

While the rise of the internet and mobile connectivity coincides with the reported decline of core discussion networks, the mixed evidence on mobile phone use and internet activities does not provide a clear link between these trends (a review of this literature can be found in Appendix A: Extended Literature Review). However, until now, no study has focused directly on the composition of core networks and the role of internet and mobile phone use.

The Personal Networks and Community Survey

In July and August 2008, the Pew Internet & American Life Project conducted a landline and cellular random digit dial survey of 2,512 Americans, aged 18 and older. The goal of this study was to replicate and expand on the methodology used in the 1985/2004 GSS to measure core discussion networks. We wanted to explore the relationship between internet and mobile phone use and the size and composition of core discussion networks. Specifically, the intent was to address issues raised by McPherson, Smith-Lovin, and Brashears in their 2006 work that suggest that internet or mobile phone users disengage from local relations, are involved in fewer voluntary associations, have less public and more private activities, and that users of these ICTs sacrifice strong ties to confidants for a large array of dispersed social ties.

Key questions are:

- Are Americans more socially isolated than in the past?

- Has the average size of core discussion networks changed?

- Are core discussion networks less diverse and more kin centered?

- Is the use of the internet and mobile phones associated with social isolation or smaller, less diverse core networks?

- What role do ICTs play in the maintenance of core networks?

- Does the internet or mobile phone withdraw people from neighborhood networks or participation in local institutions?

- Is internet or mobile phone use associated with “cocooning,” or a tendency to participate less in public and semipublic spaces?

- Does the use of ICTs contribute to a large, diverse personal network, or a small, insular network?

To address these questions, it was necessary to explore the possibility that the findings of the 2004 GSS are misleading.

The Pew Internet Personal Networks and Community Survey replicated key components of the 2004 GSS survey module on social networks. In addition, we attempted to minimize any technical problems that may have biased the 2004 GSS data, including problems with question order in the GSS survey instrument, and problems with the wording of the GSS survey (a complete discussion of these issues can be found in Appendix B: The GSS Controversy).3 A key component of the approach to overcome some of the limitations of the GSS data was the incorporation of a second question in the Pew survey that asked participants to list names of people in their core network.

As in the GSS, Pew Internet participants were asked to provide a list of people in response to the question:

“From time to time, most people discuss important matters with other people. Looking back over the last six months — who are the people with whom you discussed matters that are important to you?”

Unlike the GSS, the Pew Internet survey respondents were also asked:

“Looking back over the last six months, who are the people especially significant in your life?”

[9]

[10]

Another look at the General Social Survey

[11]

The first difference is that when the GSS asked participants about those with whom they discuss important matters, respondents could provide up to five unique names; the interviewer then asked detailed questions about each name provided. The GSS interviewer also noted if the respondent provided more than five names, but did not ask questions about these additional people. The Pew Internet Personal Networks and Community Survey replicated this procedure, recording up to five names to each name generator, but to reduce survey length did not record if participants listed more than the maximum of five names.

[12, 13]

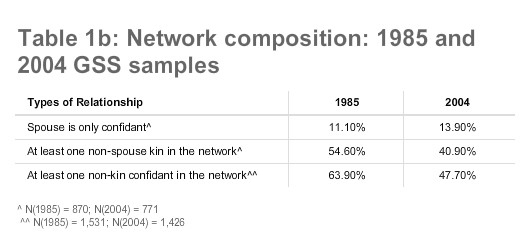

The final difference is in the analysis of spousal networks. When previous researchers calculated variables such as “spouse is only confidant” or “at least one non-spouse kin,” they did so using all survey respondents. We limit this portion of our analysis only to those who reported being married or cohabitating with a partner. Thus, our analysis of spousal networks was applied to 870 people who lived as part of a couple in the 1985 GSS (rather than the full sample of 1,531 people) and 771 in the 2004 GSS (rather than the full sample of 1,426).

Table 1a and 1b report data from the 1985 and 2004 GSS that have been structured to match the Pew Internet Personal Networks and Community Survey – capping the number of core ties at five per name generator, conforming to our understanding of what should be considered non-kin, and constrained variables that focus on spousal networks to include only those who are married.

[13]