Section 1: Americans want a privacy guarantee

Privacy has emerged as a central policy concern about the Internet as more Americans go online every day – and recent weeks have brought a ceaseless number of new allegations about privacy violations by Internet companies. In the past three months, a series of events have heightened sensitivities.

In June, the federal Office of National Drug Control Policy (the so-called “drug czar’s” office) was found to be using Internet tools called cookies to track Web surfers’ drug-related information requests. After a storm of criticism that this might allow the drug czar’s office to clandestinely record citizens’ online activities, the federal Office of Management and Budget banned the use of cookies on federal government Web sites.

In July, the Federal Trade Commission forced a bankrupt Toysmart.com to abandon its plans to sell off customer data to the highest bidder. The firm had promised site users that it would not divulge information gleaned from tracking users’ activities on the site, but a court-appointed overseer believed the customer list was a valuable asset that could be sold to help pay off the firm’s creditors. That same month, Senator John McCain (R-Ariz.) introduced legislation that would require commercial Web sites to notify consumers about what kinds of personal information they collect and how they use it. Microsoft announced new third-party cookie controls for Internet Explorer, actively warning consumers and allowing them to reject cookies, which could be used to track their activities all across the Web. Fifty Dow Chemical Company employees were fired after a search of their email revealed pornography or violent images. The Clinton Administration and the Federal Trade Commission set privacy standards so favorable for online advertisers that shares in Doubleclick rose 13 percent in one day. The FBI came under fire from Congress and civil liberties groups for developing “Carnivore,” a wiretapping device that silently intercepts all traffic to and from a suspect’s email account.

Early this month, ToysRUs.com was accused of feeding shoppers’ personal information to a data-analysis firm without revealing the relationship to consumers. In response to complaints, Toysrus.com added information to their privacy policy about how customer data is treated, but denies that the information is sold to outside vendors. One week after the customer lawsuit was filed, Amazon.com and Toysrus.com announced a strategic alliance and restated their commitment to consumer privacy online. And this past week, Pharmatrak Inc., a Boston technology firm, acknowledged tracking consumers’ activities on health-related sites without informing the public.

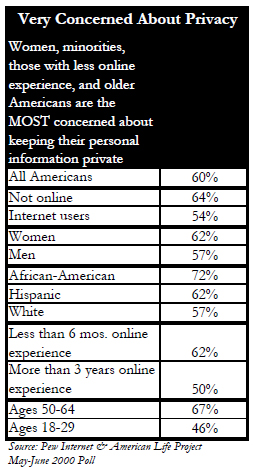

Not surprisingly, a great many online Americans are fretful about the things that could happen online and the way in which data about them might be gathered and used. An overwhelming majority of Internet users (84%) are concerned about businesses or people they don’t know getting personal information about themselves or their families. Some 54% say they are “very concerned.”

Americans want the “opt-in” option

These wired Americans are anxious to take charge of their online lives and resoundingly prefer a different privacy protection scheme from the one promoted by major Internet industry and government leaders. Seven in ten Internet users (71%) say that people who use Web sites should have the most say over how Internet companies track users’ activities.

Indeed, Internet users reject the notion that the government and Internet companies are the best stewards of their personal privacy. Two-thirds say Internet companies should not be allowed to track users’ activities and 81% contend there should be rules governing how that tracking is done. Asked who would do the best job setting those rules, 50% of online Americans said Internet users’ themselves would be best, 24% said the federal government would be best; and just 18% said Internet companies would be best.

And they are clear what that policy should be. Some 86% of Internet users favor an “opt-in” privacy policy and say that Internet companies should ask people for permission to use their personal information. This is the kind of system that has been adopted by the European Union. By contrast, the self-regulation plan recently embraced by the Clinton Administration, the Federal Trade Commission and a consortium of Internet advertisers is an “opt-out” scheme that would compel consumers to take steps to protect their privacy.

Many will share information – if they can choose when and where

When Internet users are given the choice between sharing their personal information or not being able to use a Web site, 54% have provided their real email address, name, or other personal information. Of those who have never done this, 23% (or 10% of all Internet users) say they are willing to provide that information in order to use a site. This two-thirds majority (64%) demonstrates that many Internet users are willing to enter into an exchange with Internet companies. That said, a solid majority of Internet users still do not think companies should track their behavior online without asking users’ permission.

The making of cookies

The strong urge of online Americans to protect their privacy and put the onus on companies to get permission before exploiting data or passing it along to others is a pipe dream considering the current privacy arrangements on most Internet sites. Cookies are bits of encrypted information deposited on a computer’s hard drive after the computer has accessed a particular Web site. The Web site stores these bits of information so when the same site is accessed again by that same computer, the Web site can recognize the computer and provide the same layout, shopping cart, search information, or even user’s name with the exact personalization each time the site is visited. (No reliable figures exist about how many Web sites install cookies.) Some cookies track the activities of a user at a particular Web site. Others can track the user from Web site to Web site.

Netscape created cookies in 1994 as a special browser feature to make life easier for people browsing the Web. The concept is similar to that of a computer’s preferences file. It keeps track of how the user wants a site to look or function. Once the preferences are set, the user does not have to input routine information upon each visit. Its creators thought it would be especially useful in enabling “shopping cart” services on Web sites. The idea was to allow consumers to click from page to page choosing items to buy, while a virtual clerk kept track of the items until the consumer was ready to check out. Cookies also allowed a site owner to observe which displays attracted the consumer’s attention and which needed some sprucing up. Netscape did not initially inform consumers about the clandestine activity on their hard drives and probably did not foresee the firestorm that would follow.

Chris Sherman has written for About.com that some believe the term cookie “comes from the story Hansel and Gretel, who marked their trail through a forest by regularly dropping crumbs along their path. Of course Hansel and Gretel used bright stones, not cookies to mark their trail; nonetheless, the legend persists.”

After the media reported on the technology in January 1996, Netscape added a tool to disable cookies for the next version of their Web browsing software. But it was not very easy to do the disabling. Web site users had cookies implanted on their machines unless they took affirmative steps to reject cookies – a classic “opt-out” scheme. A user had to dig two menu screens down in his browser to find the place to opt out of cookies. There seemed to be no anticipation at the time that the use of cookies would create a problem. In 1996, Alex Edelstein, Netscape’s product manager for Navigator 2.0, declared that cookie technology was an insignificant issue and would “blow over.”

For a while, the use of cookies exploded and there were few complaints from consumers. Cookies themselves are not inherently bad or necessarily invasive to one’s privacy. And they are instrumental in activating some of the Web’s most appealing features. Web publications like iVillage.com use cookies to identify the preferences of regular readers and then direct appealing, tailored content to them. Merchants like Amazon.com use cookies to speed ordering and to suggest products to return customers. Soon enough, Web advertisers saw the possibility that cookies could help Web sites monitor users’ activities and help discern consumer tastes. With that kind of information Web sites could deliver customized information to users.

Third-party advertising networks like Doubleclick sprang up to oversee banner ads on Web sites. These networks designed cookie files that track a user’s activities all across the Web and trigger advertisements according to each user’s apparent interests and needs. It is Web sites’ ability through cookies to glean user’s tastes and lifestyle that has led to the current debate about the appropriate ways to do tracking and maintain the privacy Americans want. In the most comprehensive and extreme cases, a Web company could build a profile of an Internet user that combines information about her purchases, her taste in music, the investment information she seeks, the health issues that concern her most, and the kind of news stories that seize her interest.

Unarmed in the privacy wars

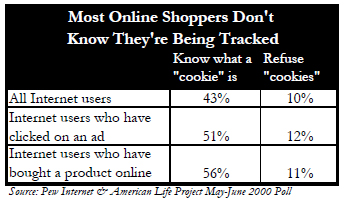

The rise of third-party ad networks has raised the issue of cookies to prominence in legal and policy-making circles. But fewer than half of Internet users are aware of cookies. Eight in ten Internet users (79%) think it’s common for Internet companies to track Web activities, yet only 43% of Internet users know that creating cookies is the way this is done. Of those who can identify cookies, just 24% set their browsers to refuse cookies. That means just 10% of all Internet users have set their browsers to reject cookies.

To a considerable degree, members of the two groups most likely to be targeted by Internet companies – those who click on ads online and those who buy things online – are unaware that their computers’ hard drives are implanted with cookies. The Pew Internet Project survey found that 69% of Internet users have clicked on a Web advertisement and about 46% have bought products online. Yet only about half of each of those groups know what a cookie is. Of those shoppers and ad-clickers who are aware of cookies, just a fifth choose to block the tracking devices and surf more anonymously (23% of ad-clickers and 20% of online buyers). That means almost 90% of Internet users who shop online are being tracked by cookies and many are unaware that is happening.

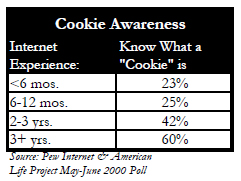

There are other notable differences between groups when it comes to cookie awareness. Men are more likely than women to say they know what a cookie is (51% of online men; 34% of online women). Internet veterans are much more likely than Internet novices to say they know what a cookie is. Sixty percent of users who have been online for three or more years know what a cookie is, compared to just 23% of new users.

The verdict on tracking

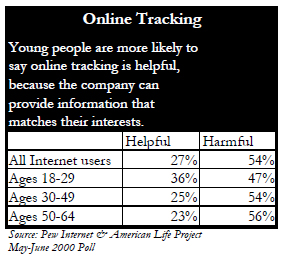

A majority of Internet users (54%) are certain that online tracking is harmful because it invades their privacy. Advocates of cookies make the case that consumers will eventually come to appreciate cookies because they allow sites to provide information that is important and relevant to an individual Web user. In the case of advertising and marketing, cookie advocates argue that there is a great deal of waste that everyone hates in mass marketing through the mails (junk mail) and the media. These advocates argue that the ideal world created by cookies and tracking is one where the clutter of information and advertisements is cut to a minimum and only useful material is put in users’ and consumers’ hands. There is a distance to go, though, before that argument persuades Internet users. Only 27% say that tracking is helpful because it allows Web sites to tailor information for users.

Richard Purcell, director of the Corporate Privacy Group at Microsoft, says that new cookie controls for Internet Explorer will be part of a set of “empowerment tools” for consumers that will soon be available in the upgraded browser. Users will be alerted when a site tries to place a third-party cookie – that is, one that could help track their activities all across the Web. “We don’t want to tell businesses how to act, beyond being truthful, but instead we want to let consumers be a force to be reckoned with,” says Purcell. Purcell believes that consumer education is the key to allaying Internet users’ fears – not behavior modification on the part of the industry.

Hard-core privacy protectionists

While online Americans say they are concerned about breaches of privacy and that control is important to them, about half of all Internet users are trusting valuable personal information to Web companies that require it. Fifty-four percent of Internet users have provided their real email address, real name, or other personal information in order to use a Web site.

Of the 45% of Internet users who have not provided real personal information to a site, 61% are hard-core privacy defenders and say they are not willing to provide that information in order to use a site. This hard-core group is more likely to believe that tracking is harmful, that online activities are not private, and that there is reason to be concerned about businesses getting their personal information. Women and men are equally likely to be in this hard-core group, as are new and veteran Internet users. Young people (18-29 years old) are more likely to say they are not willing to provide personal information, as are users who go online only from home.

Section 2: Guerrilla tactics

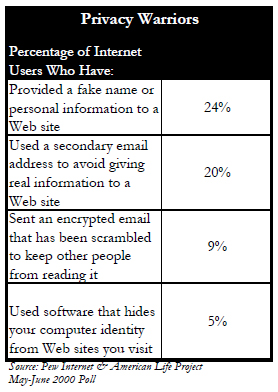

There is a small group of Internet users resorting to “guerilla tactics” to defend their privacy online. About a quarter of Internet users have provided a fake name or personal information in order to avoid giving a Web site real information about themselves. A fifth of online Americans have used a secondary email address to avoid giving a Web site real information. Just one in ten Internet users have sent an encrypted email and only one in twenty have used software that hides their computer identity from Web sites.

Men are more likely to engage in these guerrilla tactics than women. Twenty-eight percent of men have provided fake personal information to a Web site, compared to 19% of women. Twelve percent of men have used encryption to scramble their email, compared to 6% of women. Seven percent of men have used identity-masking software, compared to 4% of women.

Young people and those with more online experience are also more likely to resort to lying in order to protect their personal information. Thirty-five percent of 18-29 year olds have provided fake personal information, compared to 22% of 30-49 year olds and 17% of 50-64 year olds. Only 18% of the newest users (online for six months or less) have provided fake personal information, compared to 31% of those with three or more years of online experience.

The use of online deception tactics such as fake names highlights the compartmentalization that is the basic tool of people who want to control their privacy. Judith Donath, an MIT professor who studies identity and online behavior, says that until Web sites design spaces that are clearly public or clearly private, users will have trouble choosing what information to share and what to hide. She adds that such fundamental decisions about what to share “shouldn’t be about reading the fine print” of a Web site’s privacy policy, but instead should be as obvious as the difference between staying in the privacy of your own home versus walking down the street. When a user is in “public” Internet space such as an online store, she suggests, the user would be correct in assuming that her movements were watched. When the user was in “private” space, he would have a right to expect that nothing about his activities there would be monitored, gathered into a profile, or sold to anyone or any firm unless he authorized it. Just as people act one way in their dens and another way at a party, Internet users want to make sure that the Internet world recognizes nuances about when “public” and viewable events are occurring as opposed to “private” and sensitive communications.

Internet users are pretty savvy about at least one safeguard: passwords. Sixty-eight percent of Internet users use different passwords when they register at various Web sites. Men are more likely than women to use different passwords (72% of men, compared to 64% of women).

Section 3: A punishing mood

Internet users may not know all the tricks when it comes to protecting their privacy online, but they know problems when they see them. And if their trust is betrayed, they want vengeance.

If an Internet company violated their own privacy policy and used personal information in ways that it said it wouldn’t, 94% of Internet users said the company should be punished. When given four choices of punishment, 11% of Internet users say the company’s owners should be put in jail, 27% say the company’s owners should be fined, 26% say the site should be shut down, and 30% say the site should be placed on a list of fraudulent Web sites.

If an Internet company cheated its customers or committed a fraud online, again, 94% of Internet users said the company should be punished. When presented with the same four options, 26% of Internet users say the company’s owners should be put in jail, 22% say the company’s owners should be fined, 33% say the site should be shut down, and 13% say that placing the site on a “fraudulent site” list is the right punishment.

Men are somewhat more passionate to punish dot-com executives. Fourteen percent of online men say a privacy-violating company’s owners should be put in jail, compared to 7% of online women. Thirty percent of online men think a fraudulent company’s owners should be put in jail, compared to 22% of online women.

More experienced Internet users are also less forgiving. Thirteen percent of veteran Internet users (three or more years of experience) would put the privacy-violating executives in jail, compared to 7% of the newest users (less than six months of experience). Thirty percent of veteran users say jail is the right place for owners of a fraudulent company, compared to 23% of the newest users.

Jason Catlett, founder of Junkbusters Corp. and a privacy advocate, argues the case for punishment this way: “Many Americans know that violation of copyright is a crime, and many believe that violation of their privacy should be a crime too. Why is distributing a corporation’s software without its permission called ‘piracy,’ while distributing a person’s information without permission is called ‘sharing’?”

The Federal Trade Commission currently lacks the authority to enforce privacy standards on commercial Web sites, unless the content is directed at children. In May this year, the FTC released a report on privacy online that noted “only 20% of the busiest sites” implement the four widely-accepted fair information practices: 1) notice, displaying a clear and conspicuous privacy policy; 2) choice, allowing consumers to control the dissemination of information they provide to a site, 3) access, opening up the consumer’s personal information file for inspection, and 4) security, protecting the information collected from consumers. The commission maintained that industry self-regulation had fallen short. Even as it agreed to a self-regulation scheme with Internet advertisers, the FTC called on Congress to expand the agency’s enforcement power “to ensure adequate protection of consumer privacy online.”

Section 4: Fear vs. trust

This survey’s attempt to assess the level of trust online found three strong and sometimes conflicting patterns. In their attitudes, Internet users express considerable fears about a number of problems they might face online. They report, though, that the actual incidence of online problems is not very substantial. Finally, despite those fears, they behave in surprisingly trusting ways in many sensitive online areas. However, those fears cannot be discounted because they do seem to inhibit some groups, especially Internet novices and parents, from participating in some kinds of Internet activities.

Many anxieties

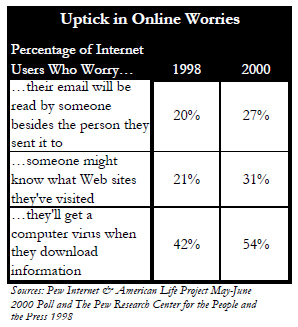

A strong sense of distrust shades many Internet users’ view of the online world and the uneasiness has grown in the past two years. Eighty-six percent of Internet users say they are concerned about businesses or people they don’t know getting personal information about them or their families. Seven in ten Internet users are concerned about hackers getting their credit card number and six in ten are concerned about someone learning personal information about them because of things they’ve done online. More than half of Internet users worry about receiving bad medical information online or downloading a virus to their computer. Nearly half of Internet users worry about seeing false news or financial reports online. Forty-six percent are not confident that their online activities are private. Only 10% of Internet users are “very confident” that the things they do online are private and will not be used by others without their permission.

Older users are more concerned than younger users about the integrity of the information they see on the Internet. Fifty-nine percent of Internet users 50-64 years old are concerned about people spreading false rumors online to affect stock prices, compared to 37% of 18-29 year old users and 49% of 30-49 year old users. Fifty-five percent of Internet users 30-49 years old are concerned about seeing false or inaccurate news reports online, compared to 40% of 18-29 year old users and 50% of 50-64 year old users.

Credit card concerns: Not much different from the offline world

It is important to understand that while Americans are concerned about their privacy online, there is no evidence in this survey that the Internet is a more menacing threat to privacy than activities in the offline world. In the case of credit card information, Americans’ online concerns are no greater than the concerns they have offline. Of all those Americans who had used their credit card to buy something over the phone, 56% said they worried about someone else getting their credit card number. Of all those with Internet access who used their credit card to buy something online, 54% said they worried about someone else getting their credit card number. And the proportion of those using credit cards online has leaped in the last five years. Only 8% of Internet users had used their credit card to make a purchase online in 1995, compared to 48% of Internet users who had done this by June 2000.

This survey found that 19% of Internet users (and 15% of all Americans) have been victims of credit-card fraud or identity theft. A vast majority of those who had been victimized (80%) said the theft occurred offline. Only 8% reported that the thief got the information because the consumer had provided it online. That means that fewer than 3% of Internet users have had their credit card information swiped online.

Viruses and unwanted email

The most frequent online problems are tied to email, but that has not seemed to affect the Internet’s most popular activity. Almost everyone who goes online (98%) knows what a computer virus is and one in four Internet users (25%) has had a computer infected by a virus. According to CERT, the Internet security emergency response team at Carnegie Mellon University, the number of “security incidents” reported held steady at about 2,400 per year in the mid-1990s. But such incidents grew to 3,700 in 1998, nearly 10,000 in 1999, and 8,836 through the first two quarters of 2000. An infected email message is the most likely suspect for Internet users who have had a virus – 46% cite that suspicion.

Users who go online from both home and work are the most fearful of computer viruses, possibly because they are more likely to have downloaded a virus and would miss the Internet the most if their access were taken away. Seventy-five percent of home-and-work users say they are worried, compared to just 51% of work-only users (who are often protected by impenetrable firewalls) and 52% of home-only users. Thirty-one percent of home-and-work users have had a computer infected with a virus, compared to 30% of work-only users and 18% of home-only users. Nevertheless, email users are very fond of this form of communication; and the people most victimized by viruses are the most likely to express affection for email. In a March 2000 Pew Internet Project poll, 83% of home-and-work users said they would miss the Internet if they could no longer go online, compared to 54% of work-only users and 71% of home-only users.

Viruses are not the only stink bombs lurking in Americans’ email in-boxes. Twenty-eight percent of Internet users have received an offensive email from someone they have never heard of. Men and women are equally likely to have received an offensive email, as are Internet users across all age, education, and income groups. Veteran users – Americans who have been online for more than three years – are the most likely to have received an offensive email from a stranger. Thirty-six percent of veteran users said that has happened to them, compared to just 14% of users with less than six months of experience online.

In a March 2000 Pew Internet Project poll, 37% of email users reported that they get a lot of spam or unwanted email messages. For those who feel inundated by unwanted email, 70% say the offending messages are sales solicitations, 17% say the emails are from other people they don’t care to hear from as much, and 7% say the unwanted emails come from list-serves, or online discussion groups.

Work surveillance and discipline

The incentive to monitor Internet users’ behavior is not simply confined to those who want to sell them products and services. There are legal encouragements to monitor online actions. Business executives can be sued if they do not maintain a safe and harassment-free work environment. That gives these executives encouragement to watch what happens on their computer systems. Moreover, the Internet is bursting with opportunities for workers to use their computers for fun or profit that is not related to their jobs. That can prompt executives to make sure workers are productively engaged when they are on the clock.

The Pew Internet Project survey shows how aggressively firms are already acting on those incentives. Eleven percent of all Americans and 17% of Internet users know someone who was fired or disciplined because of an email they sent or a Web site they went to at work. The survey suggests this kind of thing is happening most frequently at the level of those with the highest paying, most sophisticated jobs. Americans with higher levels of education and income are more likely to know someone in that situation. Fifteen percent of Americans with a college degree know someone who was fired or disciplined because of online activities, compared to 3% of Americans with have not finished high school. Nineteen percent of Americans with a household income exceeding $75,000 per year know someone in that situation, compared to 8% of those whose household income falls below $30,000 per year.

Yet many Internet users continue to conduct personal business during working hours. According to the Pew Internet Project’s four-month tracking poll, 10% of Internet users who only go online from work are surfing the Web “just for fun” or to pass the time on a typical day. In addition, on that typical day, 8% of work-only Internet users are looking for information online about a hobby or interest; 3% are looking for a new job; 4% are looking for information about books, movies, music or other leisure activities; and 5% are checking sports scores on that day.

Making friends and meeting strangers

Twenty-six percent of Internet users have responded to an email from a stranger and 25% of Internet users have made friends with someone online. Men are much more likely to respond to an email from someone they’ve never met or talked to than women. Some 31% have done that compared to 20% of women. Young people are also more likely to have responded to unexpected emails than older Internet users – 31% of 18-29 year olds have responded to a stranger’s email. After age thirty, an Internet user’s likelihood to respond drops significantly, with 25% of users between 30-49 years old and 22% of 50-64 year olds responding to a stranger’s email.

The incidence of making friends online has held steady for years. Pew Research Center polls show that 23% of Internet users reported that they had made a friend online in 1995 and a similar percentage reported that in 1998. As with responding to emails from a stranger, men are more likely to make friends online with 29% claiming an online friend, compared to 21% of women. Twenty-eight percent of those with a high school education or less have made friends online, compared to 18% of those with a college degree.

And although most Internet users are wary of other people, only 4% have ever felt personally threatened when they were online.

Dating and support-group sites

Despite their privacy concerns, Americans are finding ways to reach out to each other online. Large majorities of those who email family and friends say email is useful for these communications (88% and 90% respectively). Half of those who email friends (51%) say the electronic communication has brought them closer, while among those who email family 40% say it has brought them closer to their families.

Nine percent of Internet users have gone to a dating site and 36% have gone to a support-group site or one that provides information about a specific medical condition or personal situation. Interestingly, men are twice as likely as women to visit a dating site (12% of men have done this, compared to 6% of women). Women are almost twice as likely as men to visit a support-group site (44% of women have done this, compared to 29% of men).

Online calendars or address books

Internet users are also taking advantage of online services that aim to simplify their lives, despite their concerns about security risks. Twenty-two percent of Internet users have entrusted their personal calendar or address book to a Web site service. Internet users who upload intimate life details such as anniversaries and doctor’s appointments may well be nervous that the Web calendar company will protect their privacy. Not surprisingly, many of the sites are part of the TRUSTe privacy program and post very tough-sounding policies. For example, the Daily Drill site states, “Your calendar and all its information is absolutely private and will never ever be shown to anyone else. Period.”

Women and African-American users are more likely to use these types of sites, despite the fact that these groups are among the most frequent to say they are concerned about their online privacy.

Section 5: Why privacy concerns could limit the net’s potential

Concerns about privacy are notably higher among some groups, especially Internet novices (those who first got online within the past six months), parents, older Americans, and women. In some instances, these fears are associated with lower participation in some online activities, especially commercial and social activities. There is no way to know yet whether these groups will eventually become more comfortable and less fearful in the online world or whether their wariness will permanently limit their use of the Internet until their concerns about protecting personal information are met.

Internet newcomers and veterans

Fifteen percent of Internet users just got online in the last six months. These users are more likely to be highly concerned about privacy and Web site security than more experienced Internet users. Sixty-two percent of Internet users with less than six months of experience are “very concerned” about businesses and people they don’t know getting personal information about them or their family. In comparison, 50% of Internet users with three or more years of experience feel that way.

These pronounced privacy concerns among newer Internet users are driven in part by their fears about the technology, rather than first-hand experience with fraud or other online invasions. For example, new users are no more likely than experienced users to have been victims of any kind of credit card fraud. Some 19% of these newcomers have had their credit card number stolen, compared to 23% of Internet veterans who have suffered the same problem. And very few in each group have been victims of credit card theft online.

New users are less likely than Internet veterans to know what a “cookie” is. Among those who know what a cookie is, veteran users are the most likely to set their browser to accept them – 72% of users with three or more years of experience allow Web sites to track their activities using cookies, compared to 55% of users with two or three years of experience. The percentage of new users who block cookies is too small to accurately evaluate.

New users are much less likely than veteran users to lie to protect their personal information. Only 18% of the newest users (online for six months or less) have provided fake personal information to a Web site, compared to 31% of those with three or more years of online experience.

The more time someone has been online, the more likely they are to be confident about Web site security. For example, an equal proportion (23%) of the most experienced Internet users (3+ years of experience) and relatively new users (6-12 months of experience) have had their credit card or other personal information used without permission. But only 46% of the most experienced Internet users say they worry about online credit-card theft, compared to 70% of less-experienced users.

This lack of confidence is reflected in the fact that Internet newcomers are also less likely to purchase products or services online. Twenty-seven percent of users who got access within the last six months have bought something online such as books, music, toys, or clothing, compared to 60% of users who have been online for three or more years. Only 18% of the newest users have purchased an airline ticket or made a hotel reservation online, compared to 36% of the most experienced Internet users.

New users are more wary and less friendly online than veteran users. Just 18% of Internet users with less than six months of experience have responded to an email from someone they don’t know, compared to 34% of those with three or more years of experience. Eighteen percent of new users have made a friend online, compared to 28% of veteran users.

The parents’ story

Forty-two percent of Internet users are parents and they bring a unique perspective to the privacy debate. Eighty-four percent of parents think Internet companies should have to ask for permission to use any personal information that they collect, compared to 76% of non-parents.

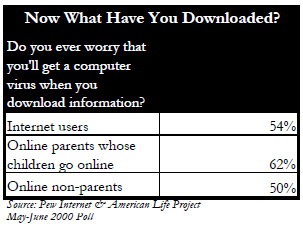

Parents with Internet access whose children also go online are much more nervous about computer viruses, perhaps out of concern that their children will unwittingly infect the family machine. Sixty-two percent of these “wired family” parents worry about downloading a virus to their computer, compared to 50% of non-parents and 54% of all Internet users.

Parents who are online are less friendly and more wary of other people than non-parents online. Only 20% of parents have responded to an email from someone they didn’t know, compared to 30% of non-parents. Parents are also less likely to make friends online – 20% of parents said they had, compared to 28% of non-parents.