In the United States, even the meaning of life can have a partisan tinge.

In February 2021, Pew Research Center asked 2,596 U.S. adults the following open-ended question: “What about your life do you currently find meaningful, fulfilling or satisfying? What keeps you going and why?” Researchers then evaluated the answers and grouped them into the most commonly mentioned categories.

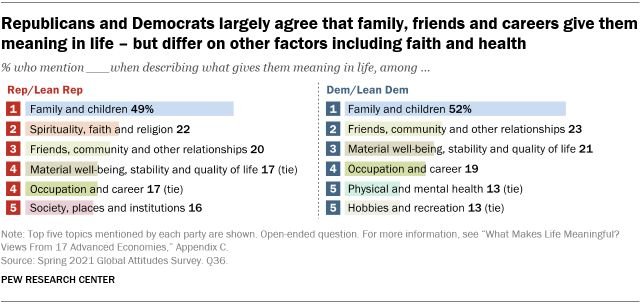

Both Republicans and Democrats are most likely to say they derive meaning from their families, and they also commonly mention their friends, careers and material well-being. But Republicans and Democrats differ substantially over several other factors, including faith, freedom, health and hobbies.

In fact, even some of the words that partisans use to describe where they draw meaning in life differ substantially. Republicans, along with independents who lean to the Republican Party, are much more likely than Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents to mention words like “God,” “freedom,” “country,” “Jesus” and “religion.” Democrats are much more likely than Republicans to mention words like “new,” “dog,” “reading,” “outside,” “daughter” and “nature.” (Democrats are most likely to mention “new” in the context of learning something new. But some also mention it in the context of new experiences, meeting new people or other forms of exploration.)

Below, we explore these partisan differences in more detail and look at how attitudes in the United States compare internationally, based on surveys conducted among 16 other publics in spring 2021.

This analysis examines Americans’ responses to an open-ended survey question about what gives them meaning in life and explores how responses in the United States differ from those elsewhere in the world.

In the U.S., Pew Research Center conducted a nationally representative survey of 2,596 U.S. adults from Feb. 1 to 7, 2021. Everyone who took part in the U.S. survey is a member of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. In the U.S., respondents were asked a slightly longer version of the question asked elsewhere: “We’re interested in exploring what it means to live a satisfying life. Please take a moment to reflect on your life and what makes it feel worthwhile – then answer the question below as thoughtfully as you can. What about your life do you currently find meaningful, fulfilling or satisfying? What keeps you going and why?”

The Center also conducted nationally representative surveys of 16,254 adults from March 12 to May 26, 2021, in 16 advanced economies. All surveys were conducted over the phone with adults in Canada, Belgium, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, the United Kingdom, Australia, Japan, New Zealand, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan. Responses are weighted to be representative of the adult population in each public. Respondents in these publics were asked a shorter version of the question asked in the U.S.: “We’re interested in exploring what it means to live a satisfying life. What aspects of your life do you currently find meaningful, fulfilling or satisfying?” Responses were transcribed by interviewers in the language in which the interviews were conducted.

Researchers examined random samples of English responses, machine-translated non-English responses and responses translated by a professional translation firm to inductively develop a codebook for the main sources of meaning mentioned across the 17 publics. The codebook was iteratively improved via practice coding and calculations of intercoder reliability until a final selection of codes was formally adopted (see Appendix C of the full report).

To apply the codebook to the full collection of 18,850 responses, a team of Pew Research Center coders and professional translators were trained to code English and non-English responses, respectively. Coders in both groups coded random samples and were evaluated for consistency and accuracy. They were asked to independently code responses only after reaching an acceptable threshold for intercoder reliability. (For more on the codebook, see Appendix A of the full report.)

Here is the question used for this analysis, along with the coded responses for each public. Open-ended responses have been lightly edited for clarity (and, in some cases, translated into English by a professional firm). Here are more details about our international survey methodology and country-specific sample designs. For respondents in the U.S., read more about the ATP’s methodology.

Words in the lead graphic were selected first by filtering to the top 100 words that are distinctive of each party, as measured by a likelihood ratio comparing the proportion of responses from Democrats who mentioned each word versus Republicans who did so, and vice versa. Words were then filtered to the top 25 based on overall frequency within each party. Words shown are used at least 50% more often by those in one party relative to the other. Words were reduced to their root form and exclude 354 common English “stop words.”

In item 6 in this analysis, support for the governing party is not the same as partisanship, but it is the best comparative measure across the 16 survey publics where partisan identification is asked (it is not asked in South Korea). Elsewhere in this analysis, we rely on traditional measures of partisanship and look at how Democrats and independents who lean Democratic compare with Republicans and Republican leaners.

Mentions of political executives were identified by searching responses for particular names as well as generic terms like “president” and “prime minister” using case-insensitive regular expressions, a method for pattern matching.

Republicans are much more likely than Democrats to cite religion as a source of meaning in their life. People in both parties mention spirituality, faith and religion as a source of meaning, with specific references to participating in traditional religious practices (e.g., “attending church services”), as well as more general references to living a life informed by faith. One Republican woman, for example, said, “My faith and the ability to choose to be thankful, optimistic and joyful are what keeps me going.”

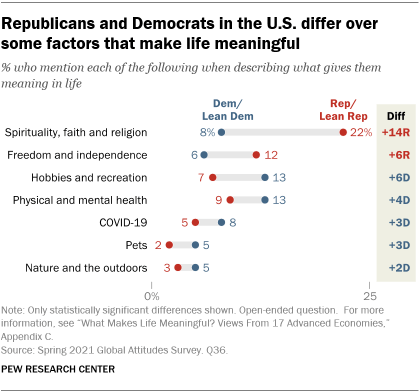

Overall, though, around one-in-five Republicans and Republican-leaning independents (22%) say spirituality, faith or religion gives them meaning in life, compared with only 8% of Democrats and those who lean to the party. Evangelical Protestants – a heavily Republican group – are especially likely to mention faith and religion as a source of meaning (34%). Smaller shares do so in other religious groups, including those following the historically Black Protestant tradition (18%), mainline Protestants (13%), Catholics (11%) and those who describe themselves as atheist, agnostic or “nothing in particular” (2%).

Republicans are also particularly likely to mention God and Jesus. One Republican man said, “Life without Jesus is meaningless, sad and hopeless. It is only through a daily relationship with Christ that joy, love, peace and goodness can be found.”

Republicans are more likely than Democrats (12% vs. 6%) to bring up freedom and independence as something that gives their life meaning. Some people mention freedom in the personal sense, focusing on their ability to live the way they want, their work-life balance, or having or wanting free time. One Republican woman said, “I like being able to have the freedoms to make my own decisions and to be able to contribute to my country. Being able to express my views without worrying about retribution.”

Others emphasize freedom in a more political sense, highlighting things like freedom of speech and religion. One Republican man had this to say: “Keeping the true meaning of being an American, country first, defending the Constitution and freedom of speech.”

Democrats are more likely than Republicans to cite physical and mental health as part of what gives them meaning in life – and they mention the COVID-19 pandemic more frequently. When the survey was fielded in February, some 13% of Democrats and 9% of Republicans mentioned health – whether people’s current state of well-being, their exercise regimens or the steps they take to lead healthy lives. For some, health is also a precursor for other sources of meaning. One Democratic man put it this way: “The biggest thing for me is health. If you don’t have your health you don’t have much. Everything else can come later but you have to have your health.”

One-in-five Americans who mentioned health also mentioned the COVID-19 pandemic, including 23% of Democrats and 17% of Republicans. And while Democrats and Republicans were about equally likely to mention COVID-19 in the context of difficulties or challenges they faced, the specifics varied by party. One Republican woman, for example, said, “My family is my only driving force. Being forced into a yearlong quarantine isn’t making that easy.” On the other hand, a Democratic woman said, “Though COVID is a constant worry, I have faith we will come through eventually and that President Biden will be able to unite our country.”

Democrats were also much more likely than Republicans to mention COVID-19 in the context of the country and where they live (23% vs. 6%) – suggesting that for Democrats, the pandemic has more of a societal dimension than for Republicans.

Democrats are more likely than Republicans to find meaning in hobbies and recreation, nature and the outdoors, and pets – though small shares of Americans overall mention these things. Overall, only one-in-ten Americans say hobbies are a source of meaning in their life, and even fewer say the same about nature (4%) or pets (3%). But Democrats are about twice as likely as Republicans to cite each one as a source of meaning in their life. Among Democrats, liberals are more likely than moderates and conservatives to find meaning in hobbies, nature and pets, but there are few ideological differences among Republicans on these topics.

Conservative Republicans are particularly likely to mention their country or where they live as a source of meaning. Among Republicans, 16% mention the country, patriotic and national sentiments, or the state of America’s economy or society as a source of meaning, compared with 12% of Democrats. But conservative Republicans (21%) are particularly likely to mention society relative to moderate and liberal Republicans (9%), while there are no major ideological differences among Democrats.

One Republican man offered a short and simple description of what gives him meaning in life: “Being born in America.” And one Republican woman said, “I am first-generation American and I think it is the greatest country in the world, and I am very grateful to live here.”

Partisanship is associated with Americans’ views about the meaning of life more than it is in other parts of the world. In most of the 17 publics surveyed, those who support the governing party and those who do not differ little when it comes to the factors that bring them meaning in life. Take the United Kingdom: Those who support the governing Conservative Party are just as likely as those who do not to mention freedom, religion and other factors as sources of meaning in their life. In fact, the sole outlying factor – out of all topics that the Center coded – is material well-being: Conservative Party supporters in the UK are slightly more likely than nonsupporters to say this brings them meaning (16% vs. 10%).

Looking more closely at the specific topic of freedom, the partisan differences that are found in the U.S. are generally not on display elsewhere. In fact, the only other place where partisan differences emerge over freedom is Taiwan, where supporters of the governing Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) are more likely than nonsupporters to mention it as a source of meaning (19% vs. 10%).

Though few mention government leaders when discussing the meaning of life, Americans are more likely to do so than people in other countries. In the U.S., 2% of people mentioned President Joe Biden or former President Donald Trump – often by name – when answering the Center’s question about where they find meaning in life. (The survey was conducted soon after Biden was inaugurated as president.)

One Republican woman, for example, said that what gives her meaning in life is “the strength and backbone taught to me by President Trump – the meaning of standing up fiercely in the face of idiocy.” On the other hand, a Democratic man celebrated Trump’s absence from office, declaring that he finds meaning in life through “job satisfaction. Enough free time and money to enjoy life. Less racial inequality. Less Donald Trump and his fanatics.”

In every other place surveyed by the Center, no more than one person – essentially 0% of the overall sample – mentioned a national leader such as a prime minister or president by name, or even the words “prime minister” or “president.”