Following industry-wide best practices, Pew Research Center has long weighted our surveys on several demographic characteristics such as age, race and education. This is to ensure that the results of our surveys represent the public’s views and behaviors as accurately as possible.

In recent years, it has also become necessary to weight our surveys on political characteristics. Since 2014, we have adjusted the surveys we conduct on our American Trends Panel (ATP) to account for party affiliation. As of June 2025, we are adjusting our surveys to match the results of the 2024 presidential election, too.

This piece explains why, when and how we are weighting our surveys on Americans’ past vote. Here are the key takeaways:

- We are weighting on 2024 presidential vote among voters for both the ATP and the National Public Opinion Reference Survey (NPORS). The ATP is a panel of about 10,000 U.S. adults who take our surveys online or by phone; it is our main vehicle for conducting domestic surveys. NPORS is an annual benchmarking survey that adults can take online, by paper or by phone.

- The overall effect of this additional weighting adjustment is less than 1 percentage point, on average. On some political questions, it makes the results slightly more Republican. On some personal finance questions, it slightly increases the influence of people who are less well-off. On questions unrelated to either of those topics, there is generally no effect. We see no evidence that the adjustment increases error.

- The small effects on our estimates may not generalize to other surveys. NPORS has a relatively high response rate compared with other surveys and – prior to weighting – includes a higher share of responses from Republicans. The ATP is already weighted on political party. Once party is accounted for, the additional effect of weighting on Americans’ past vote is not likely to be large. Surveys that use other methods may see different results.

Why weight on past vote?

Pew Research Center goes to great lengths to improve the representativeness of its surveys through weighting adjustments and by encouraging participation from groups that are less likely to answer surveys. These groups include younger adults, people who do not use the internet and people without a four-year college degree. Some of these hard-to-reach groups are more likely to be Republicans or to support Donald Trump.

In 2016, 2020 and 2024, many polls underestimated voters’ support for Trump, and our polls have not been immune. While our surveys are not designed to predict election outcomes, we regularly poll about politics and policy issues, so it is critical that Americans’ political views are accurately represented in our surveys.

In recent years, the Center has made several changes to our surveys to encourage participation from people who are less likely to respond:

- We created NPORS, an annual benchmarking survey that does a better job than other approaches at reaching Americans of many different backgrounds. NPORS produces high-quality estimates on certain questions – including the shares of U.S. adults who identify as Republicans and Democrats – that can help with weighting other surveys.

- Using the results of the annual NPORS benchmarking survey, we weight our ATP surveys to account for party affiliation.

- To encourage greater participation in our surveys, in 2024 we began offering telephone interviews with ATP panelists who don’t use the internet.

- We periodically “retire” ATP panelists to address overrepresentation of certain groups on the panel. For instance, adults with a college degree who are Democrats or lean Democratic are more likely to remain active in the panel, so we retire them at a higher rate than others.

- We’ve developed new recruitment materials that are more appealing to people who are less likely to answer surveys.

While these changes have improved the quality of our surveys on many metrics, it’s still necessary to weight our results so our polls reflect the nation’s political composition as accurately as possible. Without a past vote adjustment, our 2025 ATP surveys tended to have slightly too many Kamala Harris voters relative to Trump voters. Adding vote choice to our weighting provides an extra safeguard against the potential for political bias in our results, without increasing error.

Why weight on party affiliation and vote choice?

Party identification and vote choice are related but distinct measures. Adjusting for one goes a long way to adjusting for the other for the simple reason that most voters back the presidential candidate from the party they align with. However, many Americans vote for candidates who do not align with their party. These voters may have different political attitudes than those who stick with their party’s candidate, so adjusting for both party and vote choice ensures that we accurately capture all Americans’ attitudes. It also guards against missing dynamics that might be important.

Why now?

We began weighting on past presidential vote in June 2025. This timing was influenced by three factors:

- Our polls, as well as those of other organizations, again underestimated support for Trump in the 2024 election despite already adjusting for party affiliation.

- In spring 2025, states finished updating their records of who voted in the November 2024 presidential election. We used those official records to determine which members of the ATP actually voted. That validated turnout data is important to how we weight the ATP to past vote.

- Finally, in May 2025, a wave of new research showed that weighting on past vote tends to either improve polling accuracy or at least does not hurt it. Previous research had found that weighting on vote may harm survey accuracy.

It remains to be seen whether weighting on past vote will continue to have beneficial, error-reducing effects into the future. The efficacy of weighting adjustments can change over time as survey nonresponse patterns evolve. We will continue to monitor its impact on our surveys.

How is the Center weighting on past vote?

There are a variety of ways that pollsters go about weighting on past vote, depending on the type of survey being done and the kind of information about respondents that’s available. At the Center, we use slightly different approaches for NPORS and the ATP for just this reason.

For NPORS

We ask NPORS respondents if they voted in the most recent presidential election and, if so, for whom. Then we weight the data accordingly.

A challenge of this approach is that it relies on respondents accurately remembering and reporting what they did, which becomes more difficult the more time passes after an election. As a result, it’s inevitable that the answers for some respondents will not reflect their true voting behavior. Even so, recent studies to date have found that the benefits of weighting on past vote outweigh the risk of error due to misreporting.

It’s important to note that NPORS is a one-off survey where we have very little in the way of background information about respondents.

For the ATP

In contrast, the ATP’s panel nature allows us to improve the process in two ways.

First, because it is a panel, we are able to ask most respondents whether and how they voted immediately after an election. This helps avoid the memory errors that come from asking about elections held years prior. For people recruited into our panel after an election year, we ask them about their voting behavior at the time of recruitment.

The other difference is that for our ATP panelists, we are able to pair respondents to administrative voter data to determine which of the people surveyed actually turned out to vote. This is more accurate than relying on people’s self-reported answers about turnout. This validation is possible because we have detailed personal information for virtually all panel members.

Relevant trends in polling

Historically, most public opinion polls did not weight on past (recalled) vote, and experts have highlighted the challenges of the practice. But polling has changed dramatically in the past quarter century, and there are reasons why past vote weighting may be more effective now than in the past.

One important change is that Republican voters have become less likely to respond to surveys. Before 2016, there was no evidence that polling systematically underrepresented Republican presidential support. But that changed in 2016, and the 2020 and 2024 elections also showed such underrepresentation. A weighting adjustment is generally more effective when it addresses a consistent nonresponse pattern, rather than a nonresponse pattern that varies from election to election (which was generally the case prior to 2016).

Another key change is the evolution of public opinion polling from primarily a telephone-based endeavor (as it was from the 1980s through 2012) to primarily an internet-based one (starting around 2014).

There are two reasons why weighting on past vote may work better with online polls than phone polls. First, internet polls don’t involve an unfamiliar person asking the questions. This makes it less likely that respondents will worry about whether their answers are socially acceptable; after all, they’re just entering their responses on a screen. The lack of an interviewer may make online polls a more comfortable venue for people to admit that they voted for the losing candidate or didn’t vote at all.

Second, internet polls benefit from the rise of panel infrastructure. People in the panel are interviewed multiple times each year, and survey researchers can use respondents’ answers to older questions (e.g., “How did you vote in 2020?”) to adjust the partisan balance of the current survey of the same people.

And in the case of the ATP, we are able to measure turnout and vote choice right after an election happens, which greatly reduces errors stemming from misremembering. Phone polls, by contrast, are typically conducted with a one-time sample of Americans, and they do not have the benefit of turnout and vote choice data collected immediately after an election.

In light of Trump’s rise to political power and the migration of most surveys to online methods, research on how well past vote worked before 2016 may no longer apply. But this is not to say that weighting on past vote will work indefinitely. If pollsters are able to recapture the ability to have small errors that are random in either the Republican or Democratic direction, it may be possible to retire this adjustment.

How does past vote weighting affect the story told by the data?

Overall, weighting on past vote has a minimal effect on Pew Research Center survey estimates and, in turn, the conclusions one might draw from our polls. ATP and NPORS estimates move by less than 0.5 percentage points, on average.

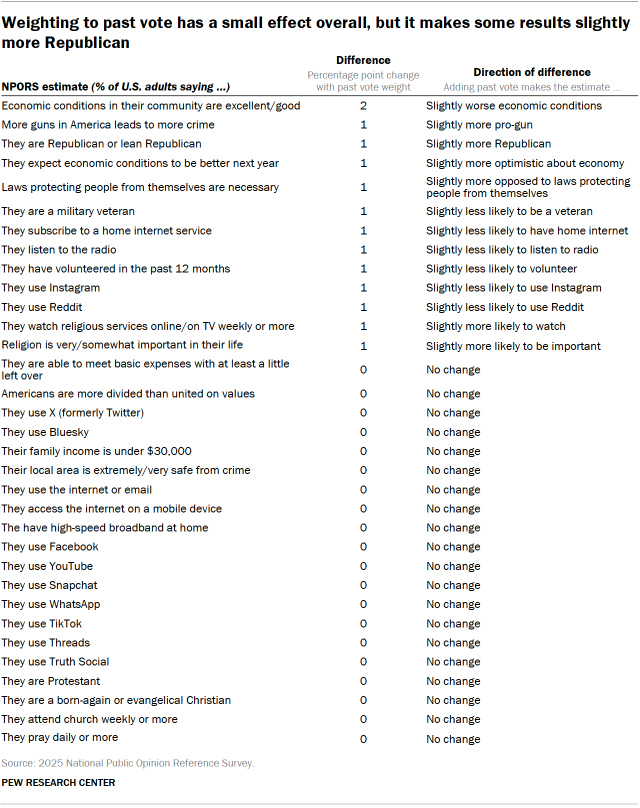

To determine how the change would affect our results, we compared weighted estimates with and without the past vote adjustment. In the latest NPORS and the April and June 2025 ATP surveys, most topline estimates did not change at all. The estimates that did change tended to reflect slightly more personal financial hardship or support for Republican positions.

For example, when weighting on past vote, ATP estimates were 1 point higher for the shares of U.S. adults who have difficulty paying for medical care and difficulty paying for child care.

In terms of politics, support for some of the Trump administration’s immigration policies were also 1 point higher with the adjustment. For example, when weighting the ATP on past vote, 39% of U.S. adults approved of suspending asylum applications from immigrants; without this adjustment, 38% favored the policy. Similarly, the shares of adults who expressed confidence in Trump to handle issues like trade, the economy and health care were all 1 point higher when weighting for past vote. Estimates for other attitudes measured (such as on taxes and tariffs) were unaffected by the weighting adjustment.

In fact, 182 of the 184 estimates in the April and June ATP surveys moved by 1 point or less with the weighting change. The only estimates that moved by 2 points were a rating of national economic conditions, which was more positive when weighting on past vote, and the share of Americans saying there is at least some discrimination of people who are transgender, which decreased when weighting on past vote.

NPORS results were similar: 32 of the survey’s 33 estimates moved by 1 point or less. The only estimate that moved by 2 points was the share of Americans who reported that the economic conditions in their community are excellent or good (a decrease). When asked about local economic conditions a year from now, the past vote adjustment made the estimate 1 point more optimistic.

In sum, the effects from this weighting decision are both small and consistent. On some political questions, weighting on past vote tends to make the results about 1 point more Republican. And on some personal finance questions, it tends to increase the influence of people who are less well-off by 1 point. On questions unrelated to either of those topics, there is generally no effect.