Note: For the latest survey data on the Supreme Court, visit our topic page.

Justice Stephen Breyer’s announcement that he would retire from the U.S. Supreme Court marks President Joe Biden’s first opportunity to put his stamp on the court. Biden’s choice, Ketanji Brown Jackson, is a federal appeals court judge and would be the first Black woman ever to serve on the Supreme Court.

As Jackson awaits confirmation hearings, here are five facts about the Supreme Court, based on surveys and other analyses by Pew Research Center.

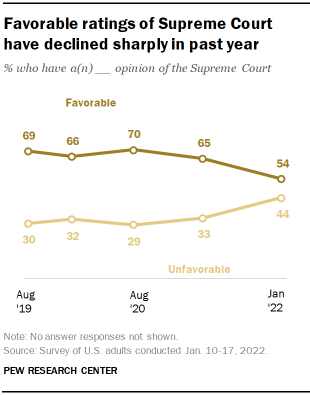

The public’s views of the Supreme Court have turned more negative in recent years. In a survey conducted Jan. 10-17, before Breyer’s retirement news, 54% of U.S. adults said they had a favorable opinion of the Supreme Court, while 44% had an unfavorable view. Over the past three years, the share of adults with a favorable view of the court has declined 15 percentage points.

The recent decrease in favorability is due in large part to a sharp drop-off among Democrats. In January, 46% of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents said they had a favorable view of the court, down from about two-thirds (65%) in April 2021. Among Democrats who describe themselves as liberal, just 36% viewed the court positively, down from 57%.

Favorable views among Republicans and Republican leaners have also dipped over the past few years, though they are largely unchanged since 2021: Roughly two-thirds (65%) continued to hold positive opinions of the court in January.

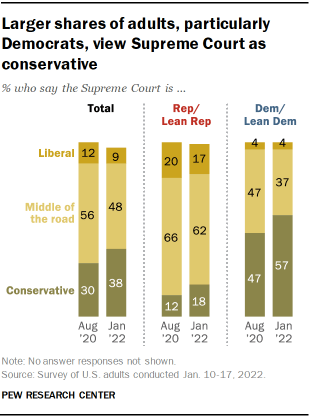

Americans’ views of the high court’s ideology are shifting. The public now perceives the court as more ideologically conservative than in past years. In January – again, before Breyer’s retirement announcement – 38% of adults said the court was conservative, an 8-point increase since August 2020. The 2020 survey was conducted prior to Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s death and then-President Donald Trump’s subsequent appointment of Justice Amy Coney Barrett as her successor.

Views of whether the high court is conservative, “middle of the road” or liberal varied by Americans’ party and ideology, especially among Democrats. In January, a majority of Democrats (57%) said the court was conservative, while 37% said it was middle of the road and just 4% said it was liberal. Nearly three-quarters of liberal Democrats (74%) said the court was conservative, compared with just 44% of conservative and moderate Democrats. Among conservative and moderate Democrats, about half (49%) said the court was middle of the road.

In the January survey, a majority of Republicans – regardless of their ideology – said that the court was middle of the road. Conservative Republicans were about twice as likely as moderate and liberal Republicans, however, to say the court was liberal (21% vs. 10%).

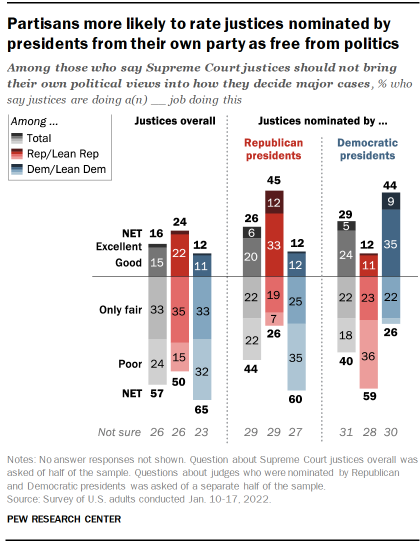

Partisans agree Supreme Court justices should not be influenced by politics, but they differ over which justices do this. A large majority of adults – regardless of party or ideology – said in January that Supreme Court justices should not bring their own political views into how they decide major cases. But there was skepticism about whether justices were living up to this ideal, and partisans were more likely to give justices nominated by a president of their own party positive assessments than they were justices nominated by a president of the opposing party.

Among the large majority of adults (84%) who said that Supreme Court justices should not bring their own political views into how they decide cases, just 16% said the justices were doing an excellent or good job in doing so. A majority (57%) said they were doing only a fair or poor job, while 26% were not sure.

Though majorities of Republicans and Democrats said that justices were not doing a good job at keeping their personal political views out of cases, Republicans were twice as likely as Democrats to say justices were doing an excellent or good job remaining politically neutral (24% vs. 12%).

On the topic of interpreting the law, more than half of Americans (55%) said in summer 2020 that the Supreme Court should base its rulings on what the Constitution “means in current times,” rather than what it “meant as originally written.” The public had been roughly divided on this question between 2005 and 2016.

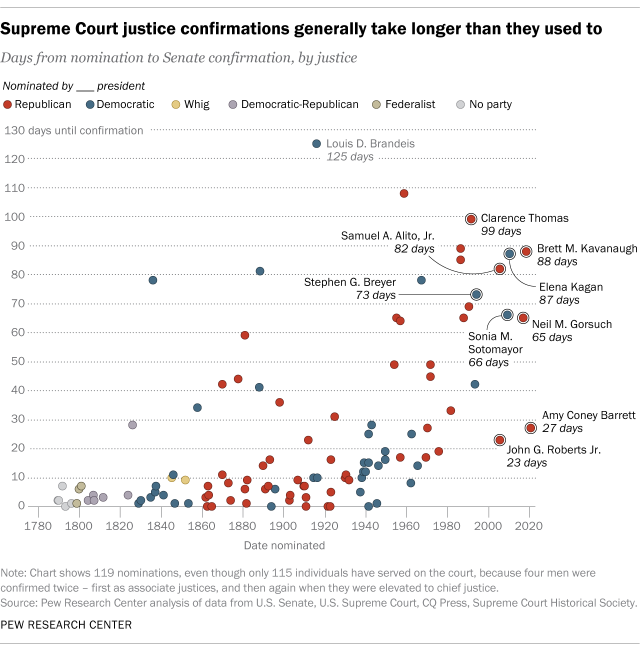

For most of the court’s 233-year history, fast and uncontroversial confirmation processes were more the norm than the exception, according to a Center analysis. Of the 115 people who’ve served on the court throughout its history, more than half (61) were confirmed within 10 days of their nominations. From the birth of the republic up to the early 1950s, the average span between nomination and confirmation was 13.2 days. But from Earl Warren in 1954 to Barrett in 2020, the time from nomination to confirmation averaged 54.4 days.

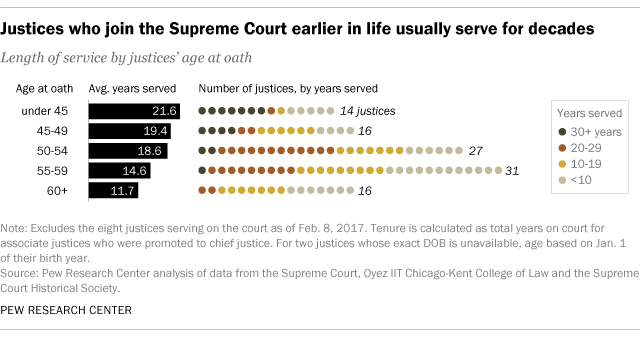

Once they take the bench, the average tenure of a Supreme Court justice is nearly 17 years, according to a February 2017 Center analysis of biographical data for the 104 former high court justices who had served by that point. (The analysis excluded the members of the court who were serving at the time and excludes anyone who has subsequently joined the court, retired or died.) Not surprisingly, younger appointees tend to stay on the court longer.

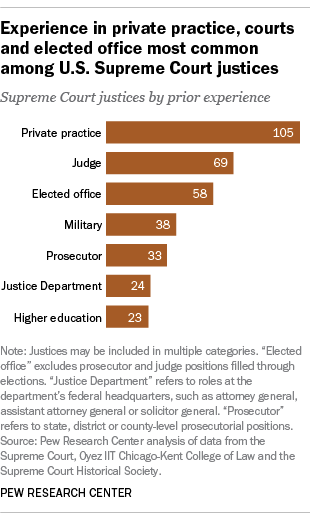

Supreme Court justices tend to come from similar backgrounds. Eight of the nine current Supreme Court justices, for example, previously served as federal appeals court judges. Only Elena Kagan did not.

A March 2017 Center analysis found that, of the 112 current or former justices at the time, the vast majority had prior experience in private legal practice. More than half had previously served as judges on either federal or state courts or held elected office.

Justices also frequently have similar educational backgrounds. About half of all justices analyzed in 2017 went to an Ivy League school. In fact, eight of the current justices attended one of two Ivy League institutions in particular: Harvard or Yale. Jackson, too, attended Harvard, while Barrett attended Notre Dame.

Demographically, nearly all Supreme Court justices have been White, non-Hispanic men. If confirmed, Jackson would become just the sixth woman ever to serve on the court, after Sandra Day O’Connor, Ginsburg and current justices Sonia Sotomayor, Kagan and Barrett. Jackson would be the first Black woman on the court. And she would be the fourth justice who is not White, the others being current Justices Sotomayor and Clarence Thomas (who are Hispanic and Black, respectively) and former Justice Thurgood Marshall (who was Black).

Only 70 of the 3,843 people who have ever served as federal judges in the United States – fewer than 2% – have been Black women, a January analysis found.

Note: This is an update of a post most recently updated on Oct. 5, 2020, and originally published on Feb. 17, 2016.