This is the second of four detailed sections in a report on Americans’ views about the role of journalists in the digital age. The report also includes an overview of the key findings.

People increasingly get news from a wide range of sources online. With that in mind, the questions in this section were intended to explore what makes someone a journalist in the eyes of the American public. We approached this from multiple angles, including the platforms that news providers use and the types of news content they produce.

Americans largely think of people who work on news content in “traditional” media as being journalists, while there is less consensus about those in “new” media.

Majorities of U.S. adults say they consider someone who writes for a newspaper or news website (79%), reports on or hosts a TV news show (65%), or reports on or hosts a radio news show (59%) to be a journalist.

Fewer say the same about people who host a news podcast (46%), write their own newsletter about news (40%) or post about the news on social media (26%).

In each of these cases, roughly a quarter of Americans say they aren’t sure whether these people are journalists, perhaps reflecting the wide variety of individuals engaged in these practices. Focus group participants indicated – and some of our survey respondents volunteered – that there are some people who do these things who they would consider journalists, and others they would not.

Focus group participants expressed mixed perspectives on individuals sharing news content via podcasts or social media, though many distinguished them from “journalists.” Some considered these sources “entertaining” but not necessarily accurate. Others appreciated the depth of storytelling individuals can offer via new media formats like podcasts and said these sources’ “hands aren’t tied like traditional media, so they’re able to … get into subjects that main news channels or specific people wouldn’t be willing to talk about.”

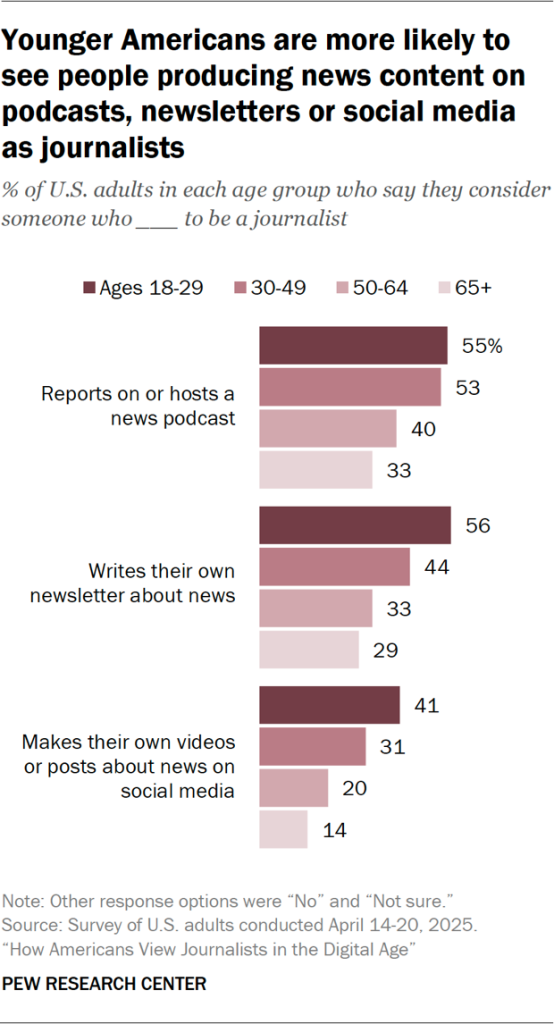

Our survey finds that these perceptions vary widely by age. Younger adults tend to be much more likely than older Americans to say that people who report on or host a news podcast, write their own newsletter about news, or make posts about news on social media are journalists.

For example, 41% of adults ages 18 to 29 say someone who posts about news on social media is a journalist, while just 14% of those 65 and older say the same.

Some younger participants in our focus groups illustrated these differences when discussing their own news sources.

For instance, one woman in her 30s said, “Back when I was a little kid, I always looked at the journalists on TV and I’m like, oh, OK, this is my news source, this is who my grandparents, my mom … went to to find out information. But now as I’m coming up as a Millennial looking at the news source, I don’t have to rely on them. I can rely on these podcasters and influencers who are actually reporting on every little thing that’s going on that I didn’t know was going on because mainstream [media] didn’t tell me about it.”

Meanwhile, differences by political party are modest. Majorities of both Republicans and Democrats agree that someone who writes for a newspaper or a news website would be considered a journalist: 83% of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents say this, as do 76% of Republicans and Republican leaners.

Republicans are slightly more likely than Democrats to consider people who host podcasts about the news (50% vs. 43%) or write a newsletter about the news (43% vs. 38%) to be journalists.

In addition to asking about the medium someone uses to discuss the news, the survey also asked respondents whether they think people who produce various types of news content are journalists.

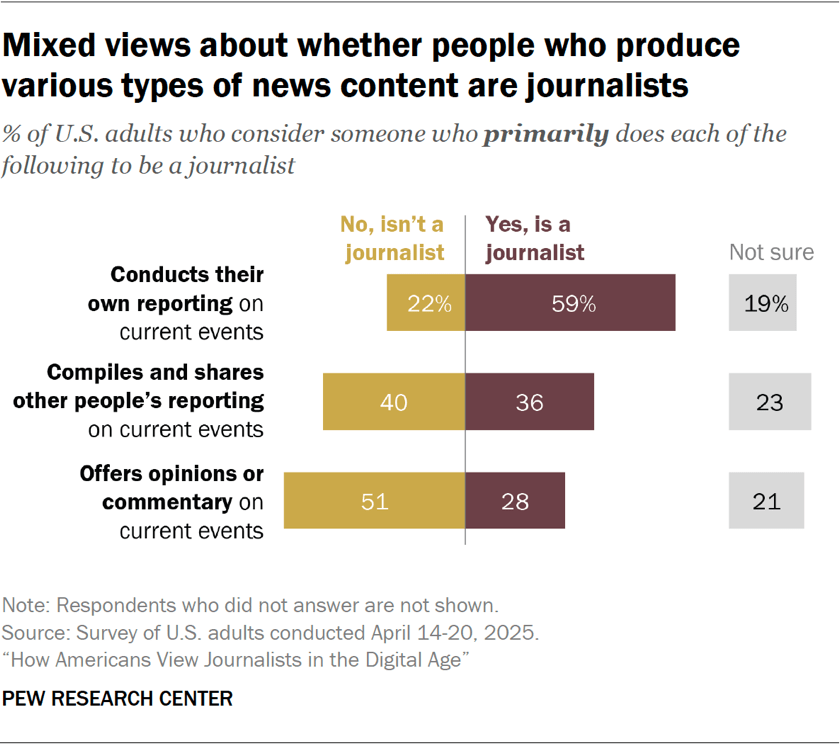

Americans are most likely to see those who primarily conduct their own reporting (59%) as journalists. Smaller shares say they consider those who compile and share other people’s reporting on current events (36%) or offer opinions or commentary on current events (28%) to be journalists.

Younger Americans are far more likely than older groups to consider each of these three types of news content producers to be journalists. For instance, seven-in-ten adults under 30 say they would consider someone who primarily conducts their own reporting on current events to be a journalist, versus 47% of those 65 and older.

Again, some respondents express uncertainty: In each case, roughly one-in-five Americans say they are not sure if they would consider someone who primarily produces each kind of content to be a journalist.

Focus group participants largely agreed that conducting “original reporting” is an important expectation they hold for journalists specifically. Several participants described compiling news as a “game of telephone,” where information can easily get “lost in translation” or opinions or bias can be introduced. As one man in his 40s explained, “Everybody whispers to the next person one word, and by the time it comes out, it’s a completely different word. When you’re just rephrasing or rewording something that’s already been out there, you lose translation there and sometimes stuff gets inaccurate. So being the first source with info is usually, in my opinion, best.”

At the same time, people’s expectations of what news providers more broadly can reasonably do vary depending on the type of source, their size and resources, and what type of news they’re covering. One woman in her 30s noted that “they all hold different thresholds.”

A woman in her 20s said, “I hold [traditional sources] to that standard. Like, they should have the resources so they should do original reporting. They should check their own facts, be involved in all of that. I don’t think I would hold smaller sources to that same standard because otherwise, if it’s one person creating their podcast, which I think is great because then they have more freedom of … not being bound by sponsors or other editing influences. But then they’re naturally more limited. They can’t be on the ground finding some of this stuff. So they naturally have to be using secondary sources.”

One man in his 20s said, “That’s also why I stay away from getting news from social media platforms – because a lot of times, it’s secondhand reporting.”

Do Americans think journalists should go through formal training?

Six-in-ten Americans say that people should have to go through formal training to be a journalist. Meanwhile, one-in-five say people should not have to go through formal training to be a journalist, while a similar share say they are not sure (19%).

Some groups are more likely to think journalists should have to go through formal training:

- Older Americans. About two-thirds of Americans ages 50 and older (67%) say formal training should be required, compared with 54% of adults under 50.

- Democrats. Democrats (69%) are more likely than Republicans (52%) to say that people should have to go through formal training to be a journalist.

- Those with more formal education. Americans with a college degree (65%) are slightly more likely than those with less education (58%) to say journalists should receive formal training.

Focus group participants shared mixed opinions about whether journalists need formal training. Those who think it is necessary said journalists who go through formal training learn ethical standards and “know how to ask the right questions.” “I think someone who has gone through the schooling and the training, the historical understanding of what journalism is and learned that from other people, either in a class or on the job, from somebody who has experience, is going to have a different perspective and pursuit of things versus someone who’s just a podcaster,” a man in his 50s said.

Some suggested journalism should be no different from other professions that require credentials. A man in his 40s said, “I think, in most professions, usually that’s what separates either someone that’s doing something amateurly from someone that’s doing something professional. We think about it in every other profession. Why not in journalism? Just because it’s easy to get into and start into doesn’t mean you still don’t need to have a certain level of professional credentials.”

Meanwhile, some participants said that other characteristics simply matter more than formal training. “It doesn’t make too much of a difference to me as long as they’re providing factual information,” a man in his 20s said.

Who gets – and prefers to get – news from journalists?

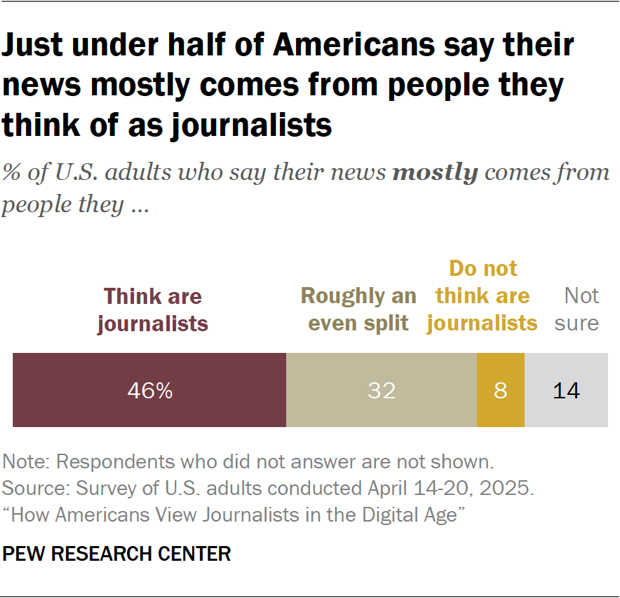

Just under half of Americans (46%) say their news mostly comes from people they think are journalists. Meanwhile, 8% of Americans say their news mostly comes from people they do not think are journalists. About a third (32%) say their news comes from roughly an even split of journalists and others.

An additional 14% of Americans say they’re not sure where their news mostly comes from, revealing the difficulty of assessing what a “journalist” is for some people in today’s media environment.

Who is more likely to get news from people they think are journalists?

- Democrats. More than half of Democrats (54%) say their news mostly comes from people they think are journalists, compared with 39% of Republicans.

- Regular news consumers. People who say they follow news at least some of the time (51%) are about twice as likely as those who consume news only now and then or hardly ever (28%) to say their news mostly comes from people they think are journalists. They’re also less likely to say they’re not sure where most of their news comes from (10% vs. 27%, respectively).

- Older adults. Americans ages 50 and older (53%) are more likely than those 30 to 49 (44%) and 18 to 29 (32%) to say their news mostly comes from people they think are journalists. The youngest U.S. adults are most likely to say their news comes from roughly an even split of people they think are journalists and those they do not (40%). And 13% say the news they get mostly comes from people they do not think are journalists.

- Higher-income Americans. A majority of upper-income adults (57%) say their news mostly comes from people they think are journalists, compared with 47% of middle-income adults and 38% of lower-income adults. Americans in the lowest income group are also more than twice as likely as those in the highest income group to say they’re not sure where their news mostly comes from (19% vs. 8%).

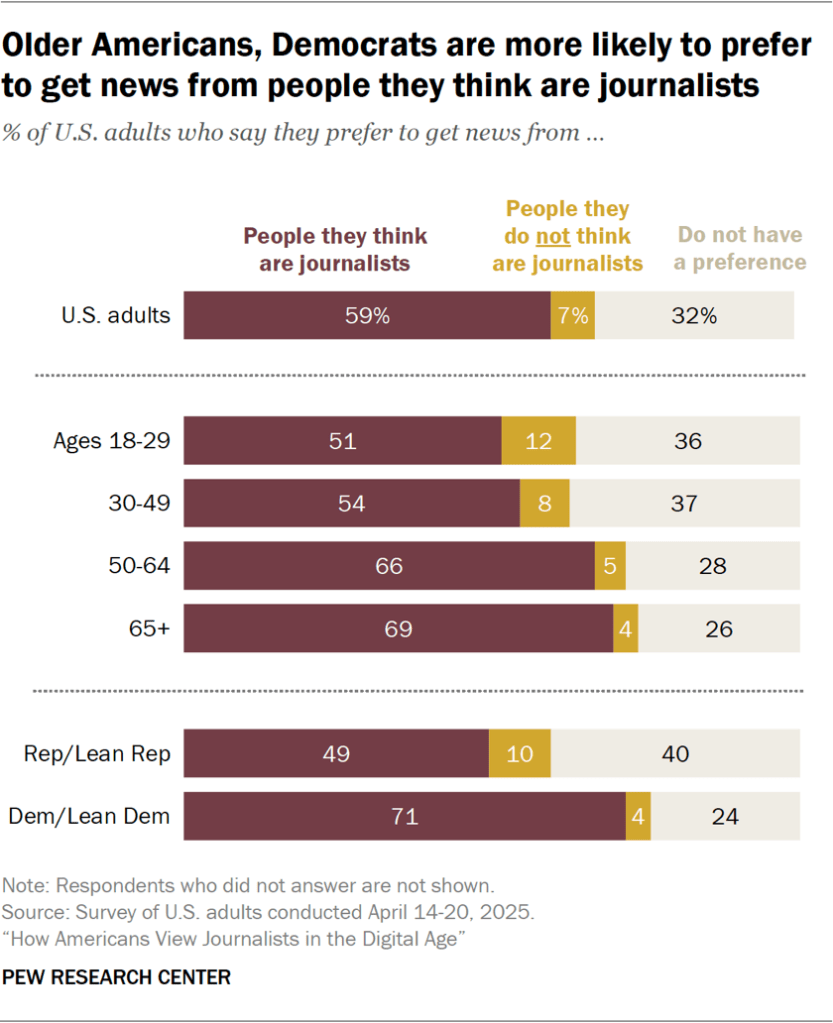

Americans are more likely to say they prefer to get news from people they think are journalists (59%) than to say their news mostly comes from people they think are journalists (46%). Only 7% of Americans say they prefer to get news from people they do not think are journalists, while about a third (32%) do not have a preference.

Aligning with their actual behaviors, Democrats are much more likely than Republicans to say that they prefer to get news from people they think are journalists (71% vs. 49%).

Older Americans also are more likely than younger Americans to prefer getting news from people they consider to be journalists.