Manufacturing jobs in the United States have declined considerably over the past several decades, even as manufacturing output – the value of goods and products manufactured in the U.S. – has grown strongly. But while most Americans are aware of the decline in employment, relatively few know about the increase in output, according to a new Pew Research Center survey.

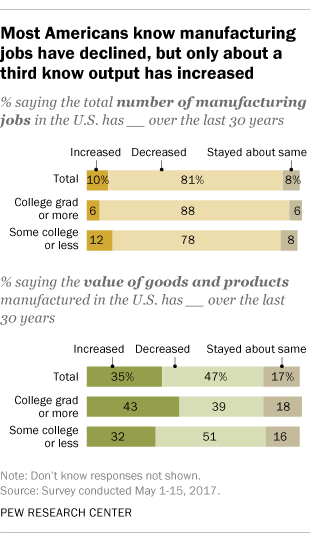

Four of every five Americans (81%) know that the total number of manufacturing jobs in the U.S. has decreased over the past three decades, according to the survey of 4,135 adults from Pew Research Center’s nationally representative American Trends Panel. But just 35% know that the nation’s manufacturing output has risen over the same time span, versus 47% who say output has decreased and 17% who say it’s stayed about the same. Only 26% of those surveyed got both questions right.

College graduates are more likely to know that U.S. manufacturing output has increased than are people with less than a bachelor’s degree. Still, college graduates are about as likely to say output has increased rather than decreased (43% versus 39%), with the rest saying it’s stayed about the same. About half (51%) of people without a four-year college degree say manufacturing output has fallen, versus a third (32%) who say it has risen.

Older people generally are more likely than younger people to believe manufacturing output has fallen. More than half (56%) of 50- to 64-year-olds, and nearly half (49%) of people 65 and older, say that’s the case, compared with 39% of 18- to 29-year-olds. Income also appears to be a factor: 42% of people earning $100,000 or more a year say manufacturing output has increased, the highest level of any income bracket, while 55% of those earning between $30,000 and $49,999 a year say output has declined.

What the numbers say

One reason Americans may be more familiar with the long-term decline in manufacturing employment than the increase in output is that the job losses have been highly visible, especially in traditionally manufacturing-intensive areas of the Midwest and South.

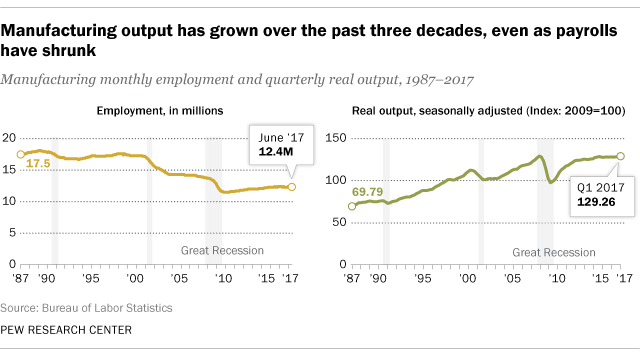

Manufacturing jobs peaked in 1979 at 19.4 million, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, and by 1987 had fallen to 17.6 million. What had been a slow decline in employment accelerated after the turn of the century, and especially during the Great Recession. Manufacturing payrolls bottomed out at fewer than 11.5 million in early 2010, and even though more than 900,000 manufacturing jobs have been added since, overall employment in manufacturing is still at its lowest level since before the U.S. entered World War II.

As a share of the overall workforce, manufacturing has been dropping steadily ever since the Korean War ended, as other sectors of the U.S. economy have expanded much faster. From nearly a third (32.1%) of the country’s total employment in 1953, manufacturing has fallen to 8.5% today.

But that doesn’t mean Americans don’t make things anymore. Last year, U.S. manufacturers made about $5.4 trillion worth of goods and products (in constant 2009 dollars), according to the Bureau of Economic Analysis. The biggest categories were food, beverages and tobacco products ($817 billion), chemical products ($752 billion) and motor vehicles and parts ($670 billion).

After adjusting for inflation, manufacturing output in the first quarter of this year was more than 80% above its level 30 years ago, according to BLS data. But while U.S. manufacturing output has increased in absolute terms, it still represents a smaller share of the economy than it used to: Manufacturing accounted for about 23% of gross output in 1997 (the first year for which such data are available) but just 18.5% last year.

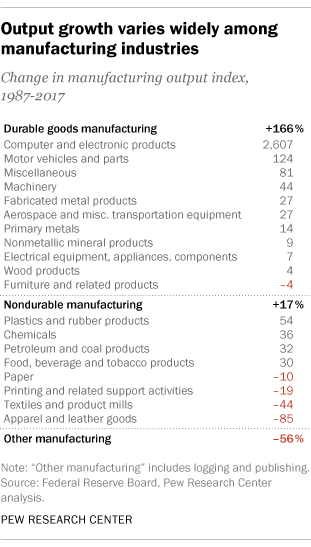

Output gains have varied widely among different manufacturing sectors. For example, according to a separate set of industrial production indices maintained by the Federal Reserve Board, computer and electronics production has soared more than 2,600% since 1987, interrupted only briefly by the Great Recession. Production of motor vehicles and parts fell steeply during the recession, but recovered strongly and is now 124% above its 1987 level. The apparel and leather goods sector, by contrast, has been on a long downhill slide: Its production index fell 85% between 1987 and the first half of this year. And while textile production fell sharply (about 52%) in the first decade of the century, it’s held mainly steady since then.

It’s important to note, however, that nearly all of the growth in manufacturing output over the past three decades occurred before the Great Recession, which had a devastating impact on U.S. manufacturing. After peaking in the first quarter of 2008, the BLS’ index of real (that is, inflation-adjusted) manufacturing output plunged 24% over the next year and a half, and only topped its pre-recession peak earlier this year.

More with less

The simultaneous increase in manufacturing output and decline in manufacturing jobs over the long term shows that American manufacturers have become far more productive than they were three decades ago – that is, they can produce more goods, or higher-value goods, with less labor.

The BLS’ index of labor productivity for manufacturing is two and a half times higher than it was at the beginning of 1987. This reflects several factors, among them businesses investing more in machinery and replacing old machines with more advanced ones; workers becoming more skilled and educated; and firms streamlining and improving their industrial processes. Economists track productivity growth closely. As Christine Lagarde, managing director of the International Monetary Fund, commented earlier this year, “it is the most important source of higher income and rising living standards over the long term. It allows us to substantially grow the economic pie, creating larger pieces for everyone.”

However, U.S. manufacturing productivity has barely budged since the beginning of 2012 – contributing to what has been some of the lowest overall productivity growth since the end of World War II. Nor is sluggish productivity growth a U.S.-only phenomenon. As a recent IMF report noted, the drop in productivity following the global financial crisis “has been widespread and persistent across advanced, emerging, and low-income countries.”

Note: Full methodology, topline and detailed tables are available here.