The coronavirus outbreak has brought renewed attention to the clinical trial process, which is used to establish the safety and effectiveness of new treatments, such as COVID-19 vaccines.

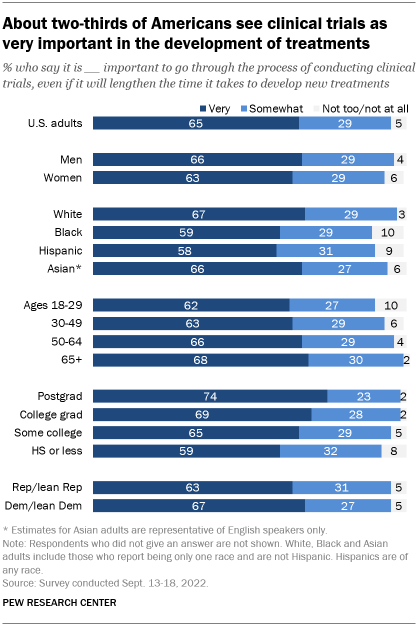

Overall, about two-thirds of U.S. adults (65%) see clinical trials as very important, despite the time such trials add to the process of developing new treatments, according to a recent Pew Research Center survey. Around three-in-ten (29%) see the clinical trial process as somewhat important, while 5% say it is not too or not at all important.

There is support for the role of clinical trials across demographic, educational and partisan groups. Majorities of Black (59%) and Hispanic adults (58%) say clinical trials are very important, as do slightly larger shares of White (67%) and English-speaking Asian adults (66%).

Pew Research Center conducted this study to understand Americans’ views about clinical trials. This analysis is based on a survey of 10,588 U.S. adults from Sept. 13-18, 2022. Everyone who took part in the survey is a member of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way, nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology.

Here are the survey questions used for this study, along with responses, and its methodology.

Focus group discussions were part of a broader Center research effort to better understand opinions about science and scientists among Black and Hispanic Americans. Six groups were held with Black adults (28 individuals in total) and six groups with Hispanic adults (29 individuals in all) from July 13-22, 2021. All focus group discussions were held virtually for 90 minutes with three to six participants in each group. Groups with Hispanic adults were conducted in English or Spanish. Group discussions were conducted by professional moderators using a guide developed by Pew Research Center. Center researchers systematically coded interview transcripts for thematic responses using qualitative data analysis software.

Here are the questions from the moderator guide and the focus group methodology.

The views of Black and Hispanic adults on this question are especially notable because these Americans were underrepresented in clinical trials for COVID-19 vaccines. Black and Hispanic participation in other kinds of clinical trials has often been too low to adequately assess whether new treatments are safe and effective across all racial and ethnic groups.

One factor in lower participation of Black and Hispanic adults in clinical trials is tied to concerns about past mistreatment in medical research, such as the U.S. Public Health Service Syphilis Study at Tuskegee or instances of medical doctors who sterilized racial and ethnic minority women without their full understanding.

A closer look at Black and Hispanic Americans’ views

Focus group discussions conducted by Pew Research Center in July 2021 highlight the range of considerations that are top of mind for Black and Hispanic Americans when it comes to whether they personally would be willing to take part in a clinical trial.

Several participants talked about the desire to help others by participating in clinical trials, and some mentioned the potential benefits to help them with a medical condition of their own. Others talked about the possible benefit from financial compensation, especially at a time in life when finances were stretched.

Here are some examples of these perspectives shared by Black and Hispanic adults who took part in the Center’s focus groups:

- “I’d do it because I think they help people, in the long run. It can help somebody, so I have no qualms with it.” – Black woman, age 40-65

- “My husband was asked [to participate in a clinical trial] because he had a transplant, and I support it. Sometimes they call him to ask questions and do research and I have always supported him because it is something to help others and for me that is important.” – Hispanic woman, age 40-65

- “I would [participate in a clinical trial], because I do suffer from migraines, so if there would be something for me to help other people who have migraines. I probably would.” – Hispanic woman, age 25-39

- “[Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease] COPD has no cure, so if I could find something that could help manage my disease better … if they can find something that controls it better, where I don’t have to keep changing medication [every four months], so I don’t have to keep taking four or five pills for hypertension, I’m all for it.” – Black man, age 40-65

- “I don’t want to be on blood thinners for the rest of my life. I honestly don’t. I don’t want to pay for that medication … If I can do away with that, yeah, I would join the study.” – Hispanic woman, age 40-65

At the same time, several focus group participants talked about balancing their desire to help others with wanting to protect themselves from potential harm. Some explained that they would not personally participate in a clinical trial because they felt there would be too much uncertainty or risk to their own health:

- “You are exposing yourself to be an experiment and be the proof either of something could [go] wrong or something could go right. And you can’t prove what are the odds on either side … So why would I expose my health to that, not knowing what could happen then?” – Hispanic man, age 25-39

- “Because basically, this is my body and I don’t really know what you’re testing on me. Anything can happen to me. I can just break down or probably anything can just happen to me. So I don’t want to take the risk. It’s unknown for me.” – Black man, 25-39

Some of those who spoke against participating in clinical trials focused on the notion of being a test case, especially given the past mistreatment of Black and Hispanic Americans in medical research:

- “I’ve seen advertising for it, or gotten emails … I don’t want to have anything tested on me. I believe in science, I do my part, but I’m not participating in that.” – Black woman, age 25-39

- “I think my perception is always like, why does it have to be me? … Why can’t someone else ‘take the L’ [loss] for a while? … Especially like just Black women in general in the U.S. have to do so much, always constantly, that I’m like, why can’t just, this one time, someone else volunteer for this research study that would enhance the importance of research as a whole?” – Black woman, age 25-39

- “Definitely, if it’s a situation where it’s going to save our lives, I’m going to sit back [and] let Brian take it first and wait a couple of hours. You know what I’m saying? But for the most part, I’m just trying to just do what I think is right. Like when they [say] the word ‘test,’ I mean, correct me when I’m wrong, anybody. It’s always, you get a test dummy, you use a mouse for a test; least significant life we use. We’ve got gerbils and mice for tests. There is just nothing that comes around with being the first. I’ve never seen anything great from being around the first person who tests up.” – Black man, age 25-39

- “It could be something for your nose, some for your lip, you don’t know what’s in it. And I told you before, and yes, they did [experiments] like that on people. That was how they coerced people to come in. ‘Well, this was for that.’ And they give these people snatch, they end up dying and having all these lifelong illnesses. So, you can’t trust that stuff. I’m no test dummy. I am not a test dummy.” – Hispanic man, age 25-39