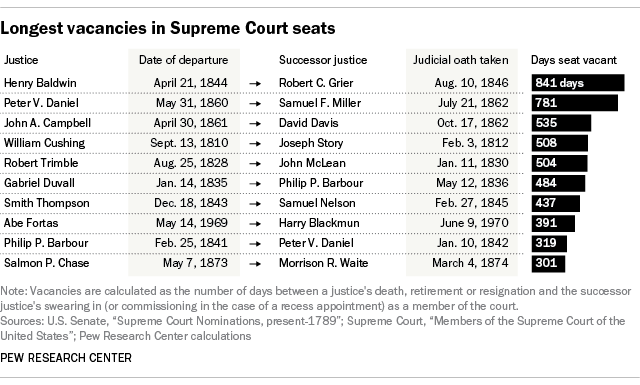

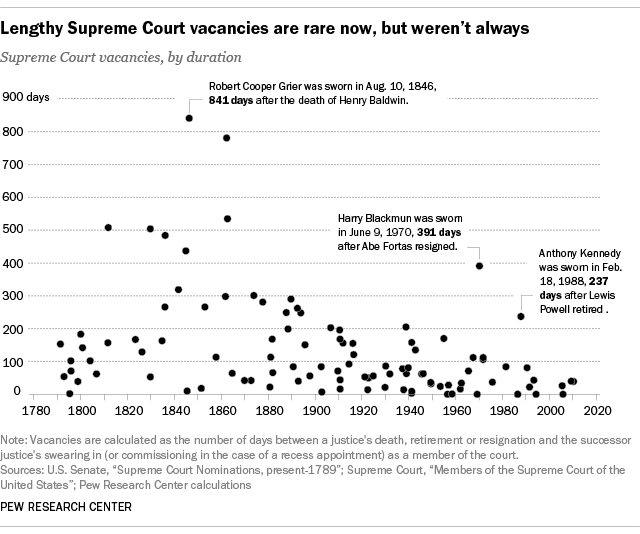

If Senate Republicans stick with their declared intention to not consider anyone President Obama might nominate to replace the late Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, his seat on the court could remain vacant for a year or more. That would be the longest vacancy on the court in nearly five decades, but by no means the longest in U.S. history.

In fact, for much of the 19th century it was not uncommon for Supreme Court seats to be unoccupied for months at a time – or, in a few cases, years. But there were only two extended vacancies in the 20th century: the 391 days from the resignation of Abe Fortas in May 1969 to Harry Blackmun’s swearing-in in June 1970, and the 237 days from Lewis Powell’s retirement in June 1987 to Anthony Kennedy’s swearing-in in February 1988. The average duration of the 15 Supreme Court vacancies since 1970 has been just over 55 days – partly because it’s become common for departing justices to make their official retirements contingent on the confirmation of a successor.

We looked at every Supreme Court vacancy since the court was established (with six justices) in 1789-90. Usually we counted vacancies as the number of days between one justice’s death, retirement or resignation and his or her successor’s formal swearing-in. For the 11 justices who first joined the court via recess appointments, we used the appointment date as the endpoint.

By far the longest gap – 841 days, or more than two years – came in the mid-1840s. Justice Henry Baldwin died in April 1844, but the mutual antipathy between President John Tyler and the Whig-controlled Senate (the Whigs actually expelled Tyler from their party) made filling the vacancy all but impossible. The Senate declined to act on any of Tyler’s nominations to fill Baldwin’s seat, and it was still open when James Polk took office in May 1845. The Senate rejected Polk’s first nominee, and his second choice declined to accept. Finally, Robert Cooper Grier was confirmed in August 1846.

That wasn’t Tyler’s only vexatious vacancy. It took him more than a year – 437 days, to be precise – and six attempts to fill the seat left open by Justice Smith Thompson’s death in December 1843. The situation deteriorated to the point where on one day, June 17, 1844, Tyler withdrew his second nominee for the seat, resubmitted his first nominee (whom the Senate had rejected earlier that year), then withdrew that nomination to resubmit the second name (to no avail, as the Senate then adjourned without considering either one).

Abraham Lincoln’s first year in office was marked by three lengthy Supreme Court vacancies (one caused by a justice’s resignation to return to his native South after the outbreak of the Civil War). As Lincoln told Congress in his first annual message, not only did the war itself complicate the process of restocking the Supreme Court, but it was tied up with the issue of reorganizing the circuit court system (at the time, each justice did double duty as a circuit judge). And, as historian David Mayer Silver has noted, since the Supreme Court was out of session from mid-March to December 1861, the vacancies “were among those tasks of President Lincoln that did not demand immediate attention.”

[a]

Lincoln finally did so, naming one new justice in January 1862 and two more later in that year (after a circuit reorganization plan became law); all of his picks were confirmed within a few days of their nomination.

Lincoln’s most famous general, Ulysses S. Grant, had Supreme Court headaches of his own after he became president. After Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase (the only Supreme Court justice named for a fish) died in May 1873, Grant offered the post to three different senators and his secretary of state, all of whom turned it down. Grant named Attorney General George Williams in December, but withdrew the nomination a month later after the Senate indicated it wouldn’t confirm Williams. Grant then named Caleb Cushing, his minister to Spain, but Cushing’s nomination also aroused vigorous opposition and was withdrawn after a few days. Finally, Grant nominated Morrison Waite, an Ohio lawyer who was so little-known that former Navy Secretary Gideon Welles commented: “It is a wonder that Grant did not pick up some old acquaintance, who was a stage driver or bartender for the place.” All told, the court went 301 days without a chief.

Grant’s travails almost make Richard Nixon’s difficulties in filling the Fortas vacancy look simple, even though that seat remained vacant longer. After Fortas resigned in May 1969, Nixon waited more than two months (to make sure his pending nominee for chief justice, Warren Burger, was confirmed) before nominating federal appeals court judge Clement Haynsworth. But Haynsworth’s nomination was fiercely attacked by civil-rights groups and organized labor, and the Senate defeated it that November.

Nixon’s second pick, G. Harrold Carswell, also drew fire – not only for racial remarks made earlier in his career, purported insensitivity to issues of gender discrimination, and his high reversal rate as a district judge, but for his alleged mediocrity. (Sen. Roman Hruska was moved to declare: “Even if he were mediocre, there are a lot of mediocre judges and people and lawyers, and they are entitled to a little representation, aren’t they? We can’t have all Brandeises, Frankfurters and Cardozos.”) Despite, or perhaps because of, that ringing endorsement, Carswell’s nomination also went down to defeat. By the time Nixon’s third pick, Harry Blackmun, was confirmed and sworn in, the seat had been empty for 391 days.