The U.S. unemployment rate was little changed in January, ticking up to 5.7% even as 759,000 more people reported having jobs, according to Friday’s report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. But the unemployed are hardly a homogenous group, and why they’re unemployed, and how long they’ve been out of work, can be just as telling about the state of the economy as the headline-grabbing jobless rate.

Fortunately, the government keeps track of the major reasons people are unemployed. (Quick refresher: To be counted as unemployed, a person must not only be out of work, but be available for work and have actively searched for a job sometime in the previous four weeks. Together, the employed and unemployed make up the labor force. Jobless people who haven’t searched for work recently aren’t considered part of the labor force and aren’t included in the count of unemployed.)

Here are four indicators drawn from Friday’s jobs report:

More people are getting back into the labor market, even if they don’t immediately find jobs.

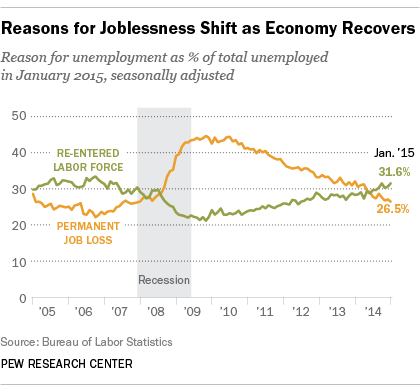

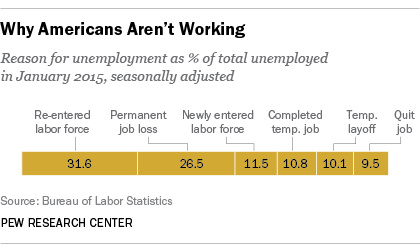

The two biggest groups of the unemployed are people who’ve lost their jobs permanently (as opposed to those who are temporarily laid off or furloughed but expect to be recalled), and people who’ve resumed their job search and thus are once again considered part of the labor force. Last month, according to BLS, 2.8 million Americans who re-entered the labor force but hadn’t yet found jobs were counted as unemployed. Those “re-entrants,” as the BLS calls them, made up 31.6% of the total unemployed population – the highest level since before the Great Recession. That’s a sign the strengthening economy is making people who’ve been on the economic sidelines confident enough about their job prospects to start looking again.

January was the seventh straight month in which re-entrants outnumbered people who’d been fired, permanently laid off or otherwise lost their jobs permanently. Last month, 26.5% of the unemployed were in this category; their share has been steadily shrinking for four-and-a-half years.

More people who want work are actually looking for it.

The number of unemployed American adults (nearly 9 million, after seasonal adjustment) is dwarfed by the number of people who aren’t in the labor force at all, most of whom don’t even want a job. In January, for instance, 87.2 million people said they didn’t want a job now; 6.5 million more said they did but hadn’t looked for work recently. That latter group surged during the Great Recession and sluggish recovery, peaking at nearly 7.2 million in May 2013.

Since then, though, public perceptions of the economy have improved, and more people are deciding to give the job market another try: The ranks of those who “want a job but haven’t looked for one lately” have fallen by 564,000 since May 2014, and the number of people who say they haven’t looked for work because they’re discouraged about their prospects fell from 837,000 in January 2014 to 682,000 last month.

More people are quitting their jobs.

When times are tough, people with jobs tend to hang on to them: Voluntary quitters accounted for just 5.5% of the unemployed in September 2010. But quits rise as workers become more confident that they can find better jobs elsewhere and don’t fear an extended period of joblessness: Last month, 9.5% of the unemployed were people who quit their jobs.

Overall, the number of “quits” began surging late last year, according to the most recent Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey. In September-November (the latest months available), 8.1 million people voluntarily left their jobs, the highest three-month quits figure since mid-2008.

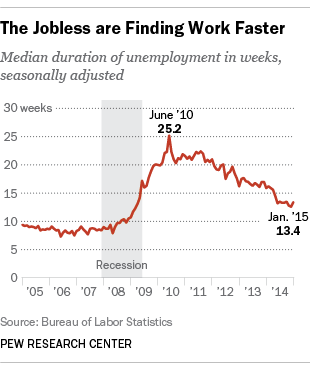

The unemployed are spending less time out of work.

The median duration of unemployment was 13.4 weeks in January, meaning half of the unemployed were out of work for a shorter time and half for longer. While a considerable improvement over the recession’s depths – median duration peaked at 25.2 weeks in June 2010 – this still is well above pre-recession levels (which typically were around eight or nine weeks).

Of the total unemployed last month, 2.4 million people (26.8%) had been jobless for fewer than five weeks, up from 24% a year earlier. The long-term unemployed, those who’ve been jobless for more than 26 weeks, accounted for 31.5% of total unemployed – again, well above pre-recession levels, but better than a year ago, when 35.6% of the unemployed had been out of work for half a year or more.