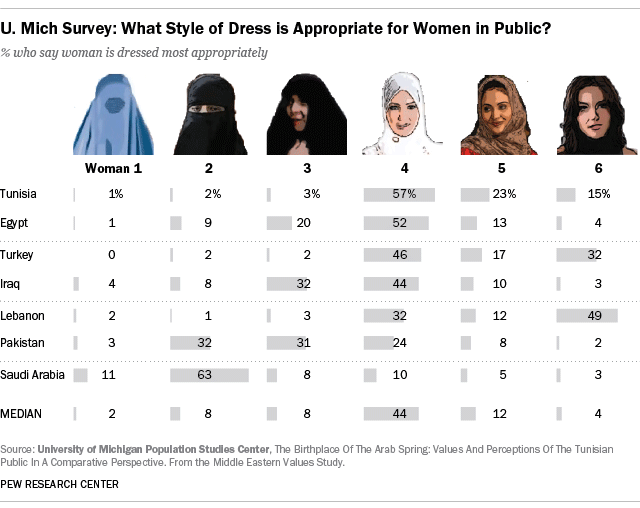

In a blog post last week, we wrote about the survey findings from seven Muslim-majority countries about women’s style of dress by the University of Michigan’s Institute for Social Research. The post generated a lot of attention in the U.S., Europe and Middle East as well as on social media and many people wanted to know more about how the research was conducted and the results, such as the dress preference expressed by men compared with women.

We went back to the researchers and asked them to share more data and to talk to us more about their methods and their findings. Here’s our Q&A with lead researcher Mansoor Moaddel, a Professor of Sociology at the University of Maryland and a Research Affiliate at the University of Michigan’s Population Studies Center.

Why did you decide to include the question on dress styles of Muslim women in your survey and what did you hope to learn?

Moaddel: First, let me begin by explaining a little bit about our survey project. The key objectives of this project are to (1) explain variation in religious fundamentalism among these seven countries; (2) determine the extent of the penetration of Western values into these countries; and (3) explain variations in attitudes among people living in these countries when it comes to issues such as gender equality, secular politics and religion. Our questionnaire consisted of more than 250 items.

The question on the style of dress was part of a section of questions that asked people about their attitudes toward the social status of women in the family, politics, job market and education. Gender issues have been the integral component of the cultural debates among intellectuals and political activists in the Muslim world since the 19th century.

The rise of the modern secular state in places like Egypt, Iran and Turkey in the 1920s provided a favorable context for women to engage in movements for their rights. In Egypt, for example, following the 1922 declaration of independence, female activist Huda Shaarawi founded the Egyptian Feminist Union and discarded her face veil, and many upper-class women followed her example. Beginning in the late 1920s, women slowly forced their way into the Egyptian University. In Iran and Turkey, forcing women to unveil later became the state’s official policy.

In their efforts to maintain the institution of male supremacy, the Islamic fundamentalists, on the other hand, attacked the women’s movement at what they thought was its weakest point — the freedom to dress as they wish. As one of the chief spokespersons of Shia fundamentalism, Iranian Ayatollah Morteza Motahhari reframed the debate on the veil by equating unveiling with nudity, which he called an epidemic, “the disease of our era.” This issue has a very long historical pedigree; the pundits and ordinary people have debated the veil for well over 100 years.

It is not just a cultural issue. It also revolves around the question of individual choice, gender equality and a woman’s control over her own body and sexuality.

We need to engage in an in-depth analysis of the data in order to fully assess the linkages between preference in the style of dress for women and other sociopolitical and cultural values. A simple correlational analysis has shown that across the seven countries, people who prefer a more conservative style also tend to be less supportive of gender equality, individual choice, secular politics, and are more strongly religious fundamentalist. It is not, however, clear whether these relationships pan out when we control for the demographics. Our more detailed methodology is explained in our report.

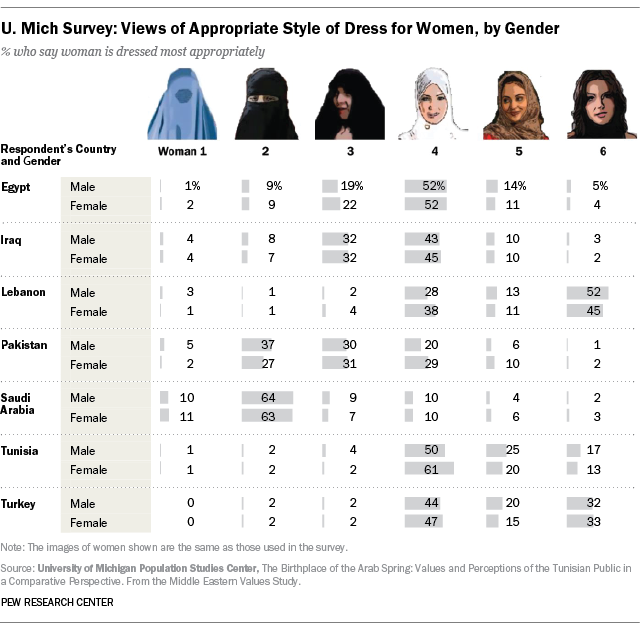

Thank you for sharing more of your demographic data with us. According to the tables, it looks like there isn’t much of a gender difference at all in the response to the clothing style question. Tell us about this.

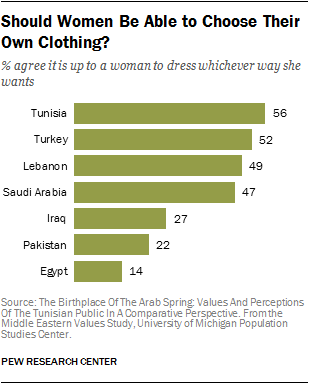

Moaddel: The bottom line is that there is no significant difference in dress-style preferences between men and women, except in Pakistan where men prefer more conservative styles. Men and women, however, differ on the issue of a woman’s right to dress as she wishes. Women are more strongly in favor of this statement than men across the seven countries. People with a university education are also more supportive of women’s choice (except in Saudi Arabia).

You also did not find much variation in response when it comes to the age of the respondent. But there are some interesting differences when it comes to education. Can you talk more about that?

Moaddel: There is a slight age difference in dress-style preference: Those 18-29 are less conservative than those 30 and above. Among demographics, the best predictor appears to be education: Those with university education are less conservative than those without university education. University education makes the largest difference in Lebanon, Turkey and Pakistan. As a whole, dress-style preference is a good predictor of liberal or fundamentalist orientations. People who are more in favor of Western-style dress are also more liberal (more in favor of individual choice, gender equality and secular politics) and less supportive of religious fundamentalism.

What challenges did you face in designing a single question to measure dress style preferences? In other words, how did you come up with the question wording you used to ask about the style of dress?

Moaddel: A comparative cross-national survey about people’s values requires that all the questionnaire items carry the same meaning for the respondents across the countries. Although we had asked questions on veiling in the previous surveys, in this project we realized that it was nearly impossible to write a single question that adequately captures all the nuances and variation in people’s understandings of the Islamic hijab or Islamic modesty. The concept meant different things to different respondents across the seven countries.

In the Iranian context for example, there is a wide range of views on the veil from the religious perspective. For the Shia fundamentalists, the truly Islamic hijab is wearing a black chador (veil), an outer garment or open cloak that covers from head to toe, save face and hands (picture No. 3). For other conservative or moderate Muslims in Iran and other countries, a headscarf without showing any hair is the appropriate dress (picture No. 4). For casually conservative women, it is picture #5. For secular Muslims, it is No. 6. For Sunni fundamentalists in Afghanistan, the proper dress is a burqa, an enveloping outer garment (picture No. 1). In Saudi Arabia and other Persian Gulf Arab countries, the proper clothing for women is a niqab, or mask, a piece of cloth that covers the face, in addition to the black cloak that covers from head to toe (picture No. 2).

Why did you choose to use photos and illustrations of different dress styles as part of the question?

Moaddel: By showing these pictures to respondents, we in effect collapse six questions into one. In this case, there is little room for misunderstanding. We understand what the respondents meant when they pointed to one of the six pictures as an appropriate dress for women. In our previous surveys, it was hard for us to interpret such responses such as “It is important for women to observe Islamic hijab” both within and across countries.

The use of images and photos can sometimes be a more effective way of measuring and understanding people’s perceptions of an issue, event or social institution. People often pass judgment on things as they physically appear to them.

What factors did you consider in determining which images of women you showed? Can you provide more detail about what distinctions you were trying to make with the image selection – for example, what is the difference between photos 3 and 4?

Moaddel: These pictures are based on variations in different types of dress that we know exist in Muslim-majority countries. The pictures show variation from very conservative to liberal style. The difference between No. 3 and No. 4 is that No. 4 is wearing a headscarf. No. 3 is wearing a chador. She always must use one hand to hold it in place; it is draped over her head. With woman No. 4, her hands are free, she has mobility and she can work. For those in Muslim countries, they would instantly recognize the differences.

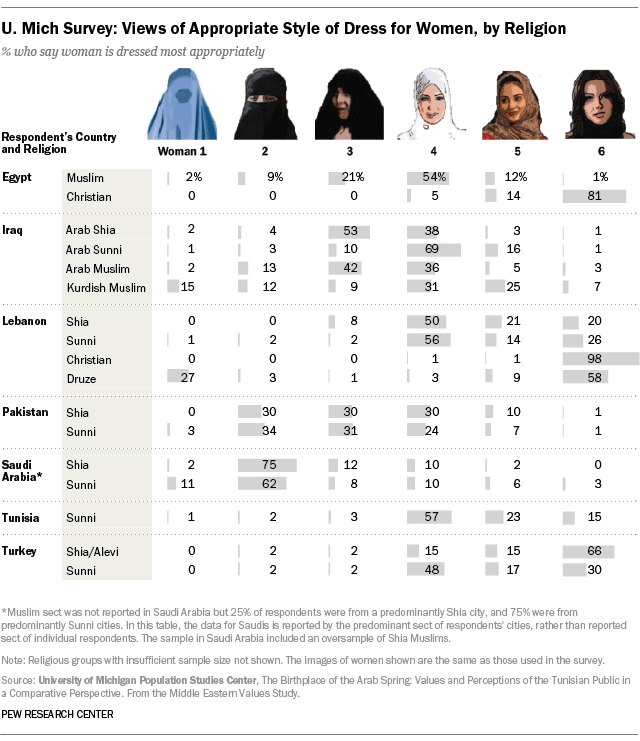

The responses when broken down by religion are also really interesting to look at. Again, any surprising results considering the makeup of the countries you surveyed, such as Egypt, Iraq, Lebanon?

Moaddel: Definitely Christians were much more liberal in that sense than Muslims, both in Lebanon and in Egypt. The differences are not so great as to be particularly surprising among Shia and Sunni.

The Saudi differences were very interesting. Saudis were more supportive of individual choice than Iraqis, Egyptians and Pakistanis, but in terms of dress style they are more conservative. One surprise was that Iraqi Kurds have become more conservative. In previous surveys, they were becoming more liberal. There is a reverse trend going on.

How did you choose the seven countries you surveyed in? Some who have commented on your findings wonder why Indonesia, the world’s largest Muslim country, was not included.

Moaddel: There are several reasons. First, these are all important Middle Eastern countries. In some of these countries, such as Egypt, Iraq, Saudi Arabia and Turkey, prior survey data were available. The existence of prior survey data on questions related to identity, gender role, religion and religiosity, for example, allowed us to ask questions so that we could track trends in values in order to assess whether these societies are moving toward religious fundamentalism or liberal nationalist values over time. We included Lebanon for comparative study of Sunnis, Shias and Christians, controlling for the national context. The addition of Tunisia and Pakistan expanded the range of cross-national variation in values — Lebanon, Tunisia and Turkey are more liberal, or rather less conservative, while Egypt, Iraq, Pakistan and Saudi Arabia were more conservative.

We also conducted the survey in Iran and Syria. However, the data from Iran were corrupt – pretty much fabricated — and therefore rejected. In Syria, by the time the pilot study was completed, the civil war was intensifying and it was too dangerous to carry out the survey there.

In Iran the people in charge of the survey basically made up responses. They completed a few hundred questionnaires and then basically cut and pasted the rest. We used a program that tries to find identical responses. On 100 variables, we found several hundred identical responses. It would be unheard of if even two were identical. They were very bad at cheating. We got a partial refund.

[to poll in Indonesia]

Did you ask Muslim women what style they personally wore and did that differ at all from what they thought was appropriate for Muslim women to wear in their country?

Moaddel: No, we did not ask that question. However, we presumed that what women thought was an appropriate style was also what they wore. The question was asked of both male and female respondents.

We do not, however, discount the issue of preference falsification. Based on anecdotal evidence and personal observation of Saudis or Egyptians, for example, we may reasonably argue that the findings have a degree of conservative bias among women and perhaps men as well. It would be hard, however, to determine to what extent this bias had affected their responses.

Talk about some of the important differences in interviewing in a Muslim country than in the United States. Were the interviewers and respondents matched by gender, that is did men interview men and did women interview women? If so, why was this done?

Moaddel: There are considerable differences. Individuality, individual choice, and privacy appear to have meanings in the Middle East that are quite different from our understanding of these concepts in the United States. In the U.S., people who are 18 or older are considered adult by law. Their independence is acknowledged and recognized by their parents. An adult is an adult, whether male or female. In some of the Middle Eastern countries, on the other hand, a man may sometimes get offended if his wife or daughter is randomly selected for an interview and he is not. In cases such as this, the interviewers were instructed to interview him as well, without his responses being included in the final data set used for analysis. In some cases, the male guardian does not allow interviews to proceed in private. In some countries, like Saudi Arabia, the interviewers and respondents are matched by gender. In Lebanon or Turkey, this is not always necessary.

We have recorded information on the interviewer’s characteristics—age, gender, education, dress-style—in order to assess the interviewers’ possible effect on responses.

Social survey research is one of the most powerful tools in the social sciences. It allows researchers to collect a goldmine of information from a large population in a very short period of time, using the probability sampling procedure. For it to be effective, people must be able to freely express their feelings and perspectives on issues. Under the authoritarian political and social environment, there is a higher likelihood that people may falsify their true preferences. One way to help remedy this problem is to interpret survey data in light of findings from other types of research, including the work of anthropologists and historians.

The other way is to formulate more than one question in measuring people’s attitudes toward an issue.

When a woman was interviewed at her home, was her husband or another male in the family with her when she was questioned?

Moaddel: In some countries, yes, this was the case and we have recorded those instances. But in other countries, we don’t know, because in some countries they did not record it.

What, if anything, surprised you about the results?

Moaddel: Findings from the survey in Saudi Arabia were particularly interesting. While over 70% of the Saudi respondents mentioned the most conservative type of dress as the appropriate style (pictures No. 1 and No. 2), at the same time a much higher percentage of Saudis (47%) than Egyptians (14%), Iraqis (27%) or Pakistanis (22%) support freedom of choice for women to dress as they wish.

These two facts in Saudi respondents cannot be easily reconciled. For sure, we know from public opinion research that people simultaneously hold opinions that clash. Nonetheless, there is significant evidence that the Saudi public is supportive of liberal values of social individualism, democracy and lesser interference into their daily lives by the religious institutions. For example, a much higher percentage of Saudis believe that love is the basis for marriage (compared with Egyptians, Iraqis, Tunisians or Pakistanis). Seven-in-ten (70%) of Saudis consider democracy to be the best form of government. There also has been a significant decline in Saudis’ trust in religious institutions between the 2003 and 2011 surveys.