When casinos come to town, an increase in public corruption is likely to follow.

Or so claim two economists who studied federal corruption conviction rates in states before and after they legalized casino gambling. They focused on the years 1985 to 2000, a period of intense efforts by the casino industry to legalize casinos in new states.

Economists Douglas M. Walker and Peter T. Calcagno found that corruption convictions increased after casinos were legalized. But that’s not the whole story. According to their analysis, the corrupting influence of casino interests was at work a year or two before casinos were legalized, too.

“Interestingly, when we examine the individual states’ trends in per capita corruption convictions, we find the trends tend to be increasing both before and after casinos are legalized and begin operating,” they report in the latest issue of the journal Applied Economics.

Walker and Calcagno say the patterns they detected are consistent with two leading theories to explain increases in corruption in casino states, and they suggest there’s more than just a correlation between the two. They say the increase in public corruption convictions before states approve casinos is evidence that the casino industry is attracted to states with what these researchers called an existing “culture of corruption.”

At the same time, the rise in public corruption convictions after legalization suggests that casino interests also are “able to capture regulators, yielding a more favorable regulatory atmosphere, but perhaps tainted by corruption.” (They note that there are “numerous examples” of how state regulations that limit casino revenues were relaxed by states after casinos opened their doors.)

To detect patterns of corruption, these researchers used a sophisticated statistical technique called Granger causality analysis to examine federal corruption convictions as recorded by the U.S. Department of Justice in all 50 states from 1985 to 2000.

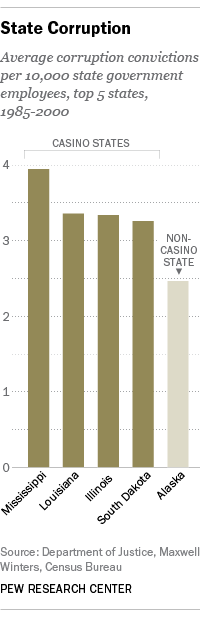

When they did a simple analysis of the average number of corruption convictions for every 10,000 state employees, four out of the five states with the highest annual rates of public corruption were casino states.

Mississippi led the list with almost four public corruption convictions a year per 10,000 state employees followed by Louisiana, Illinois and South Dakota. At the same time, none of the five states with the lowest corruption rates had legalized casino gambling during the study period.

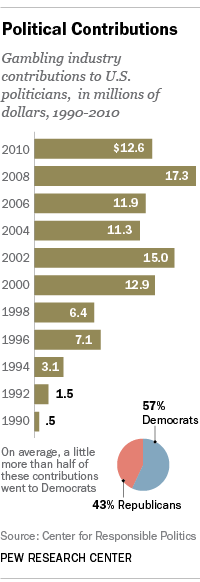

The researchers also documented the legal flow of industry money to politicians nationally. According to their analysis, total contributions to U.S. politicians rose from about half a million dollars in 1990 to $12.6 million in 2010. Overall, Democratic candidates got a larger share of gambling dollars than Republicans (57% vs. 43%).