Black pastors hold a storied place in American history. During the eras of slavery and racial segregation, they played pivotal roles in Black communal efforts to “uplift the race” (a phrase commonly used in the 19th and 20th centuries). This often included organizing job training, after-school mentoring, insurance collectives, athletic clubs and other community service programs through their churches in addition to leading protests against racial discrimination. The achievements of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and other clergy during the civil rights movement rank among the most celebrated efforts in this realm.

Indeed, King’s successes are so well known that they may have fostered a misperception that all Black clergy were bold civil rights activists. In reality, many Black clergy did not support King’s approach during his lifetime. (See Chapter 10 for more on Black American religious history.) Still, it is clearly the case that King and a number of other Black pastors played central roles in the civil rights protests of the 1950s and 1960s, and that they are remembered today for their personal courage and effective leadership. Perhaps partly as a result, the new survey finds that a plurality of Black Americans (47%) believe that predominantly Black churches are less influential now than they were 50 years ago.

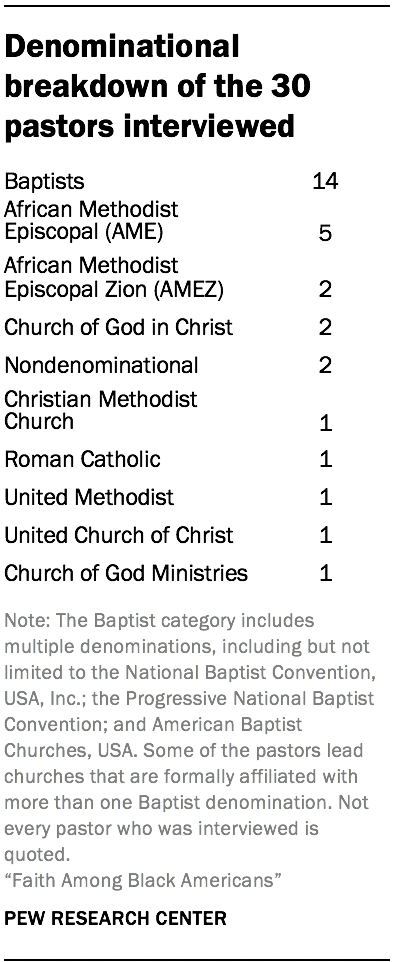

Pew Research Center sought the views of current Black clergy on this perceived decline in influence, along with other issues raised by the survey, through in-depth interviews conducted as a supplement to the survey of more than 8,600 Black Americans. Researchers at the Center spoke with 30 Black Christian clergy, most of them in senior leadership roles in congregations across the country. Although they are not representative of the opinions of all Black clergy, the interviews gave some close observers of American religious life an opportunity to discuss their experiences at greater length and in a more conversational format than the nationally representative survey.

Most of the interviews were conducted before COVID-19 closed or limited the capacities of houses of worship and prior to the protests that broke out when a Minneapolis police officer killed George Floyd. Those topics did arise in some of the later interviews and in some follow-up interviews.

Though there was a standard set of initial questions, pastors were permitted to veer from the script in the natural flow of conversations. Their answers can be summarized in four main themes:

- The pastors express great pride in the history of the Black Church, both in its historically central place in many Black communities and in the historical role of pastors as leaders in Black communities.

- The pastors generally agree that their influence, and that of their churches, in their local communities has declined in recent decades. They offered a variety of reasons, including less social activism by Black clergy, growing secularism and the consequent fraying of ties between young adults and churches, gentrification of urban neighborhoods and the departure of many congregants to less densely settled suburbs, and scandals that they feel have tainted the reputations of clergy of all races.

- Many of the pastors have changed key elements of their church services, seeking to attract young adults without alienating older congregants. This has affected the average length of services, dress codes, the kind of music played at services, preaching styles, and other aspects of worship. (In addition, the coronavirus has led to more participation in virtual services for younger and older adults alike.)

- The pastors generally are optimistic that the Black Church will survive the institutional challenges it faces, saying no other institution has risen to take on its historic role. In addition, some think that polarization of national politics in recent years has led Black people who previously worshipped at multiracial churches to decide they belong in predominantly Black churches.

Most of the clergy interviewed belong to historically Black Protestant denominations. Unlike other Christian denominations that have Black people in them, these historically Black Protestant denominations have central leaderships that are composed almost entirely of African Americans and typically promote social agendas focusing on Black populations. Because there also are Black priests and ministers in the Roman Catholic Church and other Protestant denominations, some clergy in those groups were also interviewed. The rest of this chapter summarizes the conversations that took place.

1. Pastors express great pride in the history of the Black Church

The pastors spoke proudly of “the Black Church,” generally using that term to refer to predominantly Black churches in the collective sense: thousands of churches across the country, led by Black pastors in historically Black Protestant denominations, that have long fought for Black Americans’ well-being, both spiritually and in the physical world.19

In the past, many of the pastors said, predominantly Black churches were “one-stop shopping” for Black communities – places where, in addition to worship, Black people could have rich social lives shielded from the degradations of racism that pervaded the wider society.

“For many years, Black culture was centered around the church,” said Bishop Talbert W. Swan II, senior pastor of Spring of Hope Church of God in Christ in Springfield, Massachusetts. “And I think that’s something that is very unique about the Black Church and Black religion that is not necessarily true for all other communities.”

Another pastor, the Rev. Christine A. Smith, senior pastor of Restoration Ministries of Greater Cleveland, Inc., a Baptist church in Euclid, Ohio, put it this way: “Historically, [for African Americans,] the Black Church has been the only institution that we have controlled consistently. It has been the only institution where, consistently, we’ve had a platform and we can make our voices heard strongly. … It has been a point of solace, of empowerment, of education, of camaraderie, of fellowship, and networking and opportunity.”

One widely cited role of predominantly Black churches was to provide opportunities for Black people to hold leadership roles at a time when such positions were largely unavailable elsewhere in society – and at the top of the church hierarchy was the pastor.

“In the Black Church, the pastor was the hero, the moral leader … the freest, because they didn’t work for companies in society,” said the Rev. William N. Heard, senior pastor of Kaighn Avenue Baptist Church in Camden, New Jersey. “They worked for ‘the Church,’ so they were the freest voice.”

Laypeople could also take on significant roles at church, roles that lent them stature, said the Rev. Sandra Reed, senior pastor of St. Mark AME Zion Church in Newtown, Pennsylvania: “Church was everything to the African American because it was a place where anybody could be somebody. Church became that place where Mr. Smith wasn’t just Mr. Smith, he was ‘Mr. Smith the trustee.’ … It wasn’t just, ‘I have a position,’ it was ‘I have a position with power,’ because Mr. Smith could do something that he could never have done anywhere else before. When he walked in a bank, the bank knew that was Mr. Smith, the trustee from the AME Zion Church.”

Several pastors cited the emotional, energizing experiences of worship services at predominantly Black churches as another benefit they gave to their communities. They cited the “call and response” style of sermon, in which congregants shout praise (“Amen!”) and encouragement (“You tell it, preacher!”) to pastors during their sermons, and what’s called the “whooping” (pronounced “hooping”) style of preaching, in which pastors’ voices take on distinct cadences in celebration of Jesus.20 In their interviews, some of the pastors tied the atmosphere at these services to the healing role they said their churches have played as gathering places for an oppressed population to express emotion, often through shouting or crying during services.

“How does an oppressed people express their oppression?” asked the Rev. Phil Manuel Turner, senior pastor of Bethany Baptist Church in Syracuse, New York. “You’re going to see an outsized expression. Our services serve as a grounds where people can openly cry and openly express a breakthrough. They are more exuberant. … Where else can you express how hard things have been? Where else can you have an outburst without people assuming you’re insane?”

Some of the clergy interviewed in this chapter lead predominantly Black churches in denominations that are not historically Black, such as the Roman Catholic Church, the United Methodist Church, or the United Church of Christ. These pastors said their churches do have numerous Black religious traditions, such as calling out “amen” during services or having ushers wear white. At the same time, their priorities as clergy tend to reflect those of their denominations, which are less centered around the experiences of Black Americans than is typical for historically Black Protestant denominations.

The Rev. Desmond Drummer, pastor of Most Blessed Sacrament Catholic Church in South Fulton, Georgia, said, “We are firmly in the tradition of the proverbial ‘Black Church,’ because people who are descendants of slaves are in our church.” On the other hand, he said, “Black clergy at a Catholic church are never presumed to be committed exclusively to the Black population alone, or the pan-African population alone. And that shapes the way we engage the world.”

Sidebar: Pastors say women face obstacles in becoming senior pastors at Black churches, though most Black Americans say they should be allowed to lead

It is rare for women to be the senior pastor at predominantly Black churches, especially large ones, according to the clergy interviewed for this chapter. While women commonly manage church committees and take on other important roles, only a small minority of senior pastors at predominantly Black churches are women, they said.

“We do have some very successful African American pastors who are pastoring larger congregations, but those women are the exception, not the rule,” said the Rev. Christine A. Smith, senior pastor of Restoration Ministries of Greater Cleveland, Inc., a Baptist church in Euclid, Ohio.

Seven of the 30 pastors interviewed in this chapter were women. They said that within Black Christian communities, women often struggle for acceptance as church leaders. “We are a culture that has historically put more value in the men’s voice,” said the Rev. Dr. Erika D. Crawford, who is both senior pastor at Mount Zion AME Church in Dover, Delaware, and president of the AME’s Commission on Women in Ministry. “People still see men as leaders and women as followers.”

That said, in our nationally representative survey of Black Americans, the vast majority of respondents (86%) say they believe women should be allowed to serve as the senior religious leader of a congregation, while 12% say they should not. Large majorities of both Black men (84%) and Black women (87%) say they approve of women as senior religious leaders.

Still, it is rare for women to be hired to lead churches with more than a few dozen parishioners, said the Rev. Crawford. “I have seen women overlooked for promotions. I have seen women removed from pulpits in churches for things that men do all the time. I have seen women who are qualified and prepared not get appointments.”

In 2019 to 2020, Black women comprised about half of Black enrollment for master’s degrees at seminaries in the United States, up from around a third in 1989 and 1990, according to data provided by the Association of Theological Schools.

Of the major historically Black Protestant denominations, the AME Zion Church was the first to ordain women, in 1894. Two other Black Methodist denominations, the AME Church and the Christian Methodist Episcopal Church, followed suit in 1948 and 1954, respectively. Baptist denominations have traditionally ordained fewer women (and they are harder to track through time because of the independent nature of Baptist churches). The Church of God in Christ does not ordain women as pastors. Outside these historically Black Protestant denominations, women can be pastors in the United Methodist Church, the Episcopal Church, and several other mainline Protestant denominations.

2. The pastors feel their influence has declined in recent decades

A commonly expressed view during the interviews was that Black pastors’ influence in African American communities has been declining since the civil rights movement.

To explain this, the pastors offered a variety of reasons, among them: declining social activism by Black clergy, growing secularism in society, the increasing gentrification of urban areas and scandals that have implicated clergy across racial and religious boundaries.

Less emphasis on social justice

Several of the pastors we interviewed said there is less social and political activism in their ranks than was the case decades ago, at least in part because it has proven harder since the civil rights movement for Black pastors to stake out positions in common.

“The pressures of the society are not as overt as they were,” said Dr. W. Franklyn Richardson, senior pastor of Grace Baptist Church in Mount Vernon, New York, “and the church’s response to an overt oppression is different than the current situation – where we still have racism, but it is more systemic and less overt than it historically has been.”

Still, many of those interviewed said that Black pastors as a group have not vigilantly stayed on the frontlines of the latest struggles against racism. While many Black pastors have supported protests related to the killing of George Floyd, for example, they have not been at the forefront of these protests, the pastors said.

“When you look at Black Lives Matter, this is the first time that there has been any political uprising and the church isn’t spearheading it,” said the Rev. Harvey L. Vaughn III, senior pastor of Bethel AME Church in San Diego, California. “This is a new thing. The church was not ready for that. … A lot of church people just criticized it: ‘These young people don’t move the way we used to.’”

He continued, “When you look at the violence being perpetuated against Black people, traditionally the Black Church has stood up and spoken out.” In this interview, conducted prior to the killing of George Floyd, he said, “we’ve had a lot of incidents where police officers have beaten or killed unarmed Black people, and the church has been silent.”

They had never given up protesting completely. But Black pastors are showing up to rallies and marches less often than they used to, many of the pastors said.

“It’s not [as common] as it once was,” said Dr. Benjamin Hinton, senior pastor of Tabernacle Baptist Church in Gastonia, North Carolina. “After the civil rights and integration movement there hasn’t really been as much, and I can speak of this community, there’s not a heavy political involvement, not as much as it should be or as much as it was in the past.”

The Rev. Dr. Cheryl J. Sanders, senior pastor of Third Street Church of God in Washington, D.C., said that “in the ’60s, you had maybe a high-water mark of political and social influence of religious leaders with the civil rights movement. We still have people like William Barber who is still essentially carrying out the same agenda as Martin Luther King Jr. in a very public way. I don’t want to overstate the decline of the Black minister, but the civil rights movement had a certain kind of face to it. The vanguard was religious leaders, and that has changed.”21

While they acknowledge being less activist than their predecessors, many of the pastors say they remain deeply immersed in community activities. Most of the pastors interviewed cited their involvement in at least one of the following: working to reduce homelessness, feeding the hungry, registering voters or having their church buy land to develop for affordable housing.

Dr. Patrick D. Clayborn, senior pastor of Bethel AME Church in Baltimore, Maryland, said, “In terms of engagement, we haven’t marched in protests” as much as previous generations of Black pastors, “but we have been doing things like voter registration, things like having political forums where we invite candidates running for office, feeding the hungry. We have a soup kitchen and feeding program; we serviced 100 people yesterday. … We are trying to meet needs and speak to certain issues, and make sure we are activating people at least to take the power to the ballot.”

(In a follow-up interview in October 2020, he said he thought the killing of George Floyd earlier in the year, combined with societal inequities associated with COVID-19, had led to “an increase in churches … taking a more vocal stance” advocating for Black communities. Other pastors who were recontacted offered similar views.)

Some pastors said their weekly sermons are their main method to address problems in society. The Rev. Simeon Spencer, senior pastor of Union Baptist Church in Trenton, New Jersey, said, “Am I out in the street protesting all the time? Not all the time, but I do go. I can tell you what – there’s not a single Sunday that my preaching is not in some way a form of protest against anything that I believe to be injustice.”

Several worried that too many Black pastors have devoted themselves and their churches more to the “prosperity gospel,” which links strong faith to financial success and good health, than to the traditional “prophetic role” – that is, alerting society to injustices that angered God, in the style of biblical prophets.

“Prior to the ’80s, the role of the pastor was more prophetic,” said Dr. James C. Perkins, senior pastor of Greater Christ Baptist Church in Detroit, Michigan. “The church would speak out on political issues, issues of economic justice and injustice, racism and so forth. And I think now there’s much more emphasis on prosperity than there is on prophetic ministry. Unfortunately, that’s just the way it is.”

(In a follow-up interview in September 2020, Perkins speculated that the pastors who preached the prosperity gospel are less likely to do so due to the COVID-19 pandemic. “Their message doesn’t seem to resonate with the real-life experiences that we’re having right now,” he said.)

The demands of maintaining membership in an age of declining affiliation are another reason there is less activism by clergy, according to one of the pastors interviewed.

“Because church membership is declining, we’ve put a lot of emphasis on membership, and you can’t do all things well at the same time,” said the Rev. Sandra Reed of St. Mark AME Zion Church in Newtown, Pennsylvania. “So I think we’re not as bold and courageous as we used to be. I have to say, I’m somewhat ashamed of that, because the AME Zion Church is known as the Freedom Church that was at the forefront of addressing all the ills of America, and we sort of lost that. I am trying hard to teach the young ministers coming behind me the importance of making sure they are the voice that the world can hear.”

Growing secularism resulting in low levels of attachment to churches by young adults

Another reason their influence has declined, several pastors said, is because Americans of all racial backgrounds are collectively less religious than they used to be, based on measures such as affiliation and attendance at religious services.

“I think the great change of America is, we’ve become a secular society,” said Dr. Richardson of Mount Vernon, New York.22 “A lot of people have dismissed religion to a large degree.”

Dr. Warren H. Stewart Sr., senior pastor of First Institutional Baptist Church in Phoenix, Arizona, said, “I saw it happening to the White mainline churches 30 or 40 years ago. I saw it and never thought it could happen to the Black Church, because the Black Church has been a leader in civil rights, human rights, etc. But it’s hitting all of us.”

One pastor, citing declining religious affiliation, shared his observation that fewer young parents are instilling churchgoing habits in their children, perhaps because the parents themselves never had those habits when they were children.

Dr. Hinton of Gastonia, North Carolina, said he has noticed that over the years, youth recreational groups have increasingly scheduled their activities for Sundays. He sees proof of this through his windshield on his Sunday morning drive to church.

“I ride by baseball parks, and the park is filled before 8 o’clock,” he said. “Here are these hundreds of people at the baseball field … so these kids are not in church. You got more people at one of these things than in a church.”

To him, it means that too many parents “are not putting a demand on their household, a mandate on their families, that ‘we are going to church,’ or ‘church is a priority, church is a must.’”

Gentrification in U.S. cities

Increased gentrification in urban areas was commonly cited as another challenge to the standing of Black pastors. Many of the pastors interviewed said it has led to higher property values and rents that force lower-income residents – including members of predominantly Black churches – to move away. While some congregants who have moved to the suburbs still drive back to the cities for religious services, others join suburban churches. And the higher property values lead more and more predominantly Black churches to sell their old buildings and decamp to the suburbs, where their new buildings are less central to their communities than they were in their prior, urban neighborhoods.

As for churches that remain in the cities, the higher property values make it impossible for churches to buy parking lots, the pastors said, which means congregants who commute on Sundays often struggle to park on busy city streets.

“The issue is parking,” said the Rev. Sandra Reed of St. Mark AME Zion Church in Pennsylvania. “If you have an older generation of members, they’re not going to walk to park their car and walk to church and walk back to their car. What do you do when you can’t park in front of your church, and you’re 60 or 70 years old?”

She continued, “One of my colleagues, at an AME church, had a beautiful church in center city Philadelphia. She sold it because her members were driving around the block for 15, 20 minutes looking for a parking space and couldn’t find it and went home.”

Scandals

Yet another reason they are less influential now, many of the 30 pastors we interviewed said, is because a slew of clergy scandals hurt the collective reputations of men and women of the cloth.

The Rev. Christine A. Smith of Restoration Ministries of Greater Cleveland, Inc., in Euclid, Ohio, said this is true regardless of a pastor’s denomination or race.

“When you look at what happened in the Catholic Church with the scandal with the priests, and some of the things that have happened recently, not just African American pastors, but megachurches’ pastors, or saying the Lord tells them to buy a $55 million jet, these are the kinds of things that undermine people’s faith in the church,” she said. “There was a time when the church was such a major authority in the hearts and minds of people, but these things have chipped away at that to some degree.”

Dr. Hinton said he has thought a lot recently about how the public view of pastors has declined in this regard.

“I think there has been a shift, if you will, in some communities, in some circles,” he said. “It’s nothing like it was. Pastors were highly reverent, highly respected, and I think with all the various scandals and the moral lapses and shifts in our community, it has tainted the image, the respect, the roles. … They think that all we want is the money or the self-image.”

3. Pastors have changed key components of their church services

With their congregations graying, the pastors expressed their long-felt need to bring younger adults into their churches. Making them welcome, though, comes with its challenges. Many described walking a fine line to make young adults feel welcome without driving away the older congregants who tend to be their most devoted members.

For the Rev. Dr. Erika D. Crawford, senior pastor at Mount Zion AME Church in Dover, Delaware, that balance includes ensuring that two people under 50 are always on the board. The average age of her congregants is 70, and she said she reminds them that “if you don’t get in a significant amount of people who are under 50 years old, in 10 or 20 years everyone here will be dead and there will be no church.”

The problem that needs to be managed, she and the other pastors said, is that young adults tend to have different preferences than older congregants. Where this plays out most often is in the tenor of worship services: how long they last, what people wear, what music is played and the pastor’s preaching style.

Shorter services

Several of the pastors said young Black adults prefer shorter services than are often typical at predominantly Black churches, both because they have shorter attention spans and because they want to do other things on their Sundays.

“We used to have two Sunday services, 8 and 11,” said Dr. Benjamin Hinton of Tabernacle Baptist Church in Gastonia, North Carolina. “Now we have just a 9:30 service, and then they’re free. … I try to get them out by 11:30, instead of 1 o’clock. They can go to restaurants, beat the line and at least feel like they have a full afternoon for family, fun or recreation.”

Another pastor, Dr. Warren H. Stewart of First Institutional Baptist Church in Phoenix, Arizona, said that in a nod to young people’s sensibilities, he shortened one of his two Sunday services. “We know the younger generation doesn’t want to stay at services too long,” he said, “so we cut the time from two hours to 75 minutes.”

Some pastors said that to dramatically shorten their services would upset their congregants.

“If I got up and preached 10 minutes,” said Dr. Clyde Posley Jr., senior pastor of Antioch Missionary Baptist Church in Indianapolis, Indiana, “my congregation would think I wasn’t feeling well.”

(In the survey, 53% of Black Protestants who attend Black churches at least a few times a year say the services typically last two hours or more.)

Casual dress

Younger adults, as a group, prefer dressing casually to wearing their Sunday best to services, the pastors said. Some said they have relaxed the dress code for at least some worship services offered by their churches.

Dr. Hinton of Gastonia, North Carolina, said he has adjusted his church’s dress code for most Sundays – except the first of the month, when formal dress is still expected – to meet his younger congregants’ preferences.

“Even myself, brought up in the church tradition – always suit and tie on Sunday – there are Sundays now that I’ll preach without a tie, in a casual shirt,” he said. “I’ll preach with my shirttail out – that was something that, in the Baptist church, you didn’t go to church with your shirttail out. One Sunday I wore my shirttail out with my cowboy boots and my jeans. I was comfortable. That was a total image shift from the traditional church.”

The Rev. Sandra Reed of St. Mark AME Zion Church in Pennsylvania, said that after consulting with younger congregants, she decided that her church should add a casual, shorter service to its weekend schedule. “You can come in a 5 o’clock [Saturday evening service] and be home by 6,” she said. “And you can come in in your shorts and your flip-flops. When you leave the mall, the market and the movie, you can come on by.”

Music

Musical preferences during church services form another generational fault line cited by the pastors. They say younger adults tend to prefer what is called “praise and worship” music – gospel music performed in a contemporary style by a small group of singers and musicians – in contrast to older adults, who tend to prefer traditional hymns sung by a choir.

“A lot of churches have shifted away from hymns in traditional devotional services,” said Dr. Hinton. “In this area, in a lot of churches they’re used to singing traditional hymns. But we have different generations. We try to include the hymns but we also include praise and worship [music]. That’s one of the things that has shifted.”

Churches that have not tweaked or substantively changed their music programs are struggling more than churches that have, he said. “We’ve had to tweak ours to reach a changing generation. Can’t just be singing the old hymns. There has to be some upbeat, has to be some life, has to be some modernity.”

Preaching

The pastors said their younger congregants tend to prefer a tamer style of preaching than has been traditional in many predominantly Black churches. Some said they have altered their services to reflect young adults’ preferences for what they called a “teaching style” of preaching, as opposed to the more emotional type of preaching (including “call and response” and “whooping,” referred to earlier) that have deep roots in predominantly Black churches.

“The Millennials are moving away from emotionalism to foundational teaching,” said Dr. Vernon G. Robinson, a former congregational pastor who now holds the position of presiding elder of the Batesville District of the Mississippi Conference of the AME Zion Church. “They want to understand exactly what the word of God means and how can it be applied to their life. They’re not as interested in the theatrics of worship. The ‘call and response’ type of thing is not enough for them.”

Dr. Posley of Indianapolis, Indiana, said that to appeal to younger adults’ sensibilities, he was adding a service that reflected this, as well as younger people’s musical preferences. “I’m going to present a different style,” he said. “I’m going to teach rather than preach. I’m going to have a guest each week. The Millennials will be able to interrupt the teaching and ask questions. I’m making the music more contemporary. The service will be shorter – from 90 minutes [down] to an hour.”

Virtual services

Prior to the pandemic, many pastors said they viewed online broadcasts of services mainly as a benefit for older congregants who could not make it to church in person. But as churches began bolstering their online options in 2020 after closing their sanctuaries due to the coronavirus, younger and older congregants alike have gotten more used to logging on, the pastors said.

Dr. Hinton said he has heard from younger and older congregants alike saying they watched a service online while “doing their walk around the park or working out at home, or on the deck.”

“Some younger people have gotten comfortable with having not to get up as early, not having to put on church clothes,” said the Dr. James C. Perkins of Greater Christ Baptist Church in Detroit, Michigan. “They may continue to access the services via livestream [after the pandemic]. We’ll have to wait and see what happens.”

LGBT inclusion

Several of the pastors said their younger congregants are generally more accepting of homosexuality than their older congregants, and that they walk a fine line between preaching acceptance of gay people, on the one hand, and opposing same-sex marriage, on the other. (The 2020 survey shows that young Black adults are more likely than older ones to say society should be accepting of homosexuality and that clergy should perform marriage ceremonies for same-sex couples.)

Dr. W. Franklyn Richardson of Grace Baptist Church in Mount Vernon, New York, said he senses that younger Black adults are “less theological” and “less doctrinal” than their elders on issues concerning homosexuality. He and other pastors say this can cause tension in churches associated with historically Black Protestant denominations such as the National Baptist Convention USA, Inc.; the AME Church; and the Church of God in Christ, which formally oppose same-sex marriages or prohibit their pastors from officiating at them.

For pastors, “dealing with the roles of LGBT people in the church is a conundrum,” Richardson said. “On the one hand, the Black Church is an advocate of civil rights and people’s rights. On the other hand, the Black Church is a strict interpreter of scripture.”

Black churches, he said, “have traditionally had an understanding of what marriage is, that does not make it an option between a man and a man, and a woman and a woman.”

Some clergy said they wished the atmosphere in Black churches was more accepting.

“The Black Church, though we get racism very well, we don’t get sexism and heterosexism as readily,” said the Rev. Traci C. Blackmon, associate general minister of Justice and Local Church Ministries for the United Church of Christ and formerly senior pastor of Christ the King United Church of Christ in Florissant, Missouri, a predominantly Black church. “And [while] this younger generation is more accepting of diverse expressions of sexuality, that is not necessarily the reputation of the Black Church. So we have a ways to go with making a place for everybody at God’s table.”

Dr. Patrick D. Clayborn of Bethel AME Church in Baltimore, Maryland, said, “I have on occasion made statements around equality, and that there should not be any judgment or bias.” He continued, “It’s not for us to judge and we shouldn’t be in anyone’s bedroom. I don’t necessarily delve deeply into it. I kind of stick with the idea of not hating, not condemning someone to hell, not trying to condemn someone’s life and not trying to be someone else’s God, but love that person as you’d want to be loved and let them make choices themselves. We can love them without needing to cast judgment.”

4. The pastors generally believe the Black Church will survive the challenges it faces

Given all the challenges they discussed, we asked the pastors if they thought predominantly Black churches would remain viable institutions a few decades from now. Many expressed confidence that Black religious congregations willremain an important part of Black communities, even if in diminished form, due to the continued presence of racism in the United States.

“The Black Church is in a weakened state, but I think it will still be there in 20 to 30 years,” said Dr. Warren H. Stewart of First Institutional Baptist Church in Phoenix, Arizona. “There are some who believe that the Black Church has served its purpose, but I don’t believe it. As long as there is racism, there will be a need for the Black Church. … Even though we don’t have the influence, particularly among the young, it’s still the most respected voice in the Black community.”

Another pastor, the Rev. Simeon Spencer of Union Baptist Church in Trenton, New Jersey, hit on a similar theme. He said, “As long as the country continues to, on the one hand, say: ‘There’s no such thing as race and we’re all one,’ but on the other hand effectively live as if that is not the case, as if it does matter, then we will always seek out a faith-based place to express who we are. Black people will always need somewhere that will speak specifically to their spiritual heritage and their experience in this country.”

Bishop Talbert W. Swan II of Spring of Hope Church of God in Christ in Springfield, Massachusetts, pointed to anecdotal evidence that a rise in racism and racist rhetoric over the last several years has led many Black adults to leave their multiracial churches for predominantly Black ones.

“I do see, over the last three or four years, a shifting in terms of Millennials questioning the leaderships in evangelical and other charismatic churches that have White leadership who are not speaking to the issues of systemic racism that are affecting our society today,” he said. “There are some of that demographic that are leaving those churches because they’re disillusioned with the fact that those leaders either avoid altogether or don’t speak adequately to those issues with their congregations.”

Still, some of the pastors, looking beyond 20 or 30 years, said they could foresee the possibility of further decline or even the demise of predominately Black churches, due to growing secularism or a future with less racism. And they could be OK with that.

“I think the Black Church will dissipate as the need for it does,” said Dr. Franklyn Richardson of Grace Baptist Church in Mount Vernon, New York. “If the society becomes more holistic, where people are included, the Black Church will become less and less necessary, therefore it will become diminished. It will be just ‘the church.’ … If you get to a place where society is holistic and diversity is celebrated, and people are not cowed by racism, there will be an opportunity for the church in America to be a holistic institution.”

Dr. Clyde Posley Jr. of Antioch Baptist Church in Indianapolis, Indiana, said he hopes that day will come. “I don’t think there should be a Black Church,” he said. “There isn’t a Black heaven and a White heaven. … A proper church will one day eschew the label of Black Church and be a universal church.”