The survey finds that most Black Americans who attend religious services go to congregations where most of the other attendees and the senior clergy are Black. At the same time, most Black Americans also indicate, in their answers to other questions in the survey, that they value diversity in their religious congregations. Even among those who regularly attend Black congregations, a majority say that historically Black congregations should try to diversify rather than preserve their traditional racial character.

In a series of structured, small group conversations (focus groups) that Pew Research Center facilitated, Black Americans discussed what often draws them to majority-Black congregations, while at the same time expressing a desire for religious spaces that are open and racially inclusive. These conversations highlighted several elements of the Black congregational experience that are particularly important to focus group participants, including the comfort associated with familiar styles of worship and music, sermons that are relevant to the distinctive struggles of Black Americans, and avoidance of the discrimination and discomfort that some of them have felt in non-Black religious spaces.

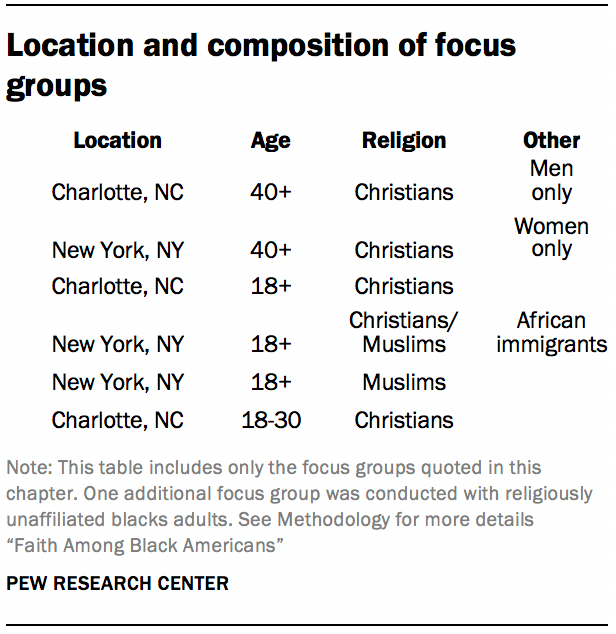

Of the six focus groups discussed below, three were limited by design to Black Protestants who regularly attend religious services, mostly in majority-Black churches. But even in the other three focus groups – comprised primarily of Muslims, adults under 30, and African immigrants – most participants had some at least some experience with, and often strong views on, Black congregations.

The quotations below are verbatim, but the names of the focus group participants have been changed to protect their confidentiality.

When asked why they go to their congregation, or how they would choose a new one, even participants who belong to historically Black Protestant denominations did not always describe their church’s racial composition as central.

Some explicitly mentioned the race of other attendees as a priority. For example, Rodney currently attends a Black church, and when asked how he would approach looking for a new place of worship, he expressed some preference for another Black church: “I probably would look more towards a Black church, but I would visit, I would visit a couple before making my decision.”

Morgan was more decisive in her preference for a Black church, saying, “One thing about Charlotte I did notice – I drove past the same Filipino churches, Mexican churches. There’s so many different churches, and I’m not going into one of those. Because … it’s not going to be my spirit and what I’m looking for.”

Natasha, who also currently attends a Black church, was even more direct, saying: “I’m not looking for no White people.”

But others were less focused on the race of the congregation. For example, Reginald attends religious services at a majority-Black church. He said that if he were to change congregations, he probably would end up attending another predominantly Black church – not because he views the race of other attendees as a priority, but just because of where he lives: “I definitely would look for nondenominational. … It has nothing to do with race. Sometimes you can’t help but go to the church in your community.”

Other participants also said they did not view it as a priority to be in a church where most or all other attendees are Black. They said they cared more about diversity in a prospective new church.

“I want diversity. … Diversity means to me, just everybody.”

– Alfred

“I’m going to go to either [a Black or non-Black church] and see where the spirit is at.”

– Philip

When talking about predominantly Black congregations, participants highlighted at least four ways in which they saw them as valuable: (1) as a place to address the distinctive needs and concerns of Black Americans; (2) as a provider of familiar rituals, worship styles and music; (3) as a shelter from discrimination and a place to feel at home; (4) and as a link to the history and struggles of Black Americans.

Across the focus groups, some discussants contended that predominantly Black churches and mosques serve the needs of Black people better than churches and mosques with other racial or ethnic compositions. For example, Lynda, who regularly attends a church where most attendees are Black, put it this way: “We are still human, but we still do things differently.” Carmen then expressed general agreement, saying predominantly Black churches are better for Black people “because I think they know our struggle.”

Dee cited the musical portions of services at her predominantly Black church as something that makes her more comfortable than she would be at churches that are multiracial or predominantly White. “When it comes to music, it’s about our struggle. … If you think about it, Blacks have – and African Americans, or whatever – have struggled more than Caucasians, so we bring it out in expressions of music. We sing hard. We sing powerful.”

Morgan made similar points about music and Black Americans’ struggle. For her, two parts of the Black congregational experience are especially important: sermons on topics that relate to her daily difficulties and the praise and worship music that lifts her up. “Every time I’m going through something … either the pastor’s preaching on it, or here comes that song that feeds my spirit and may help me to continue to have a better rest of the week,” she said.

Music plays at least two roles in their congregations, according to focus group participants. It is a source of emotional comfort and encouragement, and it also provides an element of familiarity and continuity, tying generations together. Jayla talked about it in this way: “I would be looking for music. I love a church with good, good music. A good choir, good singers. Music moves me.”

And Monica put it this way:

“I like the fact that, in the church where I go, they are bringing back the old-time religion. … The old-time religion is the music from years ago, because that’s what hit the heart. … They’ve been singing some of the contemporary gospel, but we’ve also put in the old-time gospel because that’s what hit the heart with our grandparents and our parents back in the day, and that’s what I like. They involve the children with that. The children are learning the way we were years ago and bringing it into the way we are now.”

But music is not the only source of familiarity that discussants raised in connection with Black congregations. A Muslim man, Dawud, said he recently moved to a new community and attends a mosque where the presence of other Black people around him as he prays is comforting: “I really like the [mosque] because mostly it’s like the people that I came up with … so I’m comfortable there.”

Some participants also mentioned the reverse sentiment – feeling unwelcome, or even discriminated against, in congregations where other races are the majority. Some Muslim participants, for example, said that Muslims who are Black are often treated disrespectfully and seen as less than fully Muslim at mosques where people of Arab or South Asian descent are in the majority. Fatou, an immigrant from Africa, put it this way:

“From my perspective, it [the mosque] is not a safe place to go for me, especially where I go to worship in my neighborhood. Because they’re not, like I say, they’re not my people. They are from other countries. … They don’t want to be next to you. … So sometimes I’m like, ‘Let me stay home.’”

Tanisha, a U.S.-born convert to Islam, made a similar point:

“Just because we don’t come from Muslim countries, it doesn’t make us any less Muslim than those people that were born in Muslim countries. And sometimes I feel like that’s the way we are looked at, that we are American Muslims and it’s not as good. We’re not good enough. Sometimes, that’s the way I feel when I’m around people from those countries.”

Regardless of their own preferences for where to worship, focus group participants often talked about Black congregations in a positive way because of their historical role in advocating for Black communities, including during the civil rights movement. Nikita, who attends a predominantly Black Protestant church, said she first heard the term “Black Church” while watching a television documentary.

“I heard the phrase ‘Black Church,’ and it was actually a documentary that I was watching, and it was related to the whole civil rights era. … It was the only institution where the folks who look like us could come together and really strategize a plan that would effect change. So I tuned in on the part where four little girls were bombed, and then that’s when I heard that phrase from the announcer saying four little girls were bombed at ‘the Black Church.’ So when I hear that [phrase], it kind of brings me back to that.”

On hearing Nikita’s recollection, Clarice also began to speak positively about “the Black Church”:

“The Black Church that we know, based on the documentaries that I also seen, was the gathering place for our strategizing and organizing. … That’s why the church was so important to Blacks, because we could go in there and we could talk politics. We could go in there and we could talk finance. … That was the sacred space, the safe space, that people of color could go.”

But some focus group participants, including members of majority-Black churches, expressed reservations about the term “Black church.”

Clarice said she attends religious services at a church where most participants are Black, but said that she would not consider her church a “Black church,” because she believes the racial composition of churches is incidental. “I think churches were congregated based on location, and it had everything to do with where you lived, and churches were … innate to the community, just like the store or post office … where you lived dictated the type of membership you had.” Like some other participants, she also pointed out that majority-Black churches are not the only ones where she has heard music that moved her. “The Word is for anyone, right? I’m curious to know how you necessarily define a ‘Black church.’ [Because] I know White churches that sing good gospel, too. I was in Japan – they got one of the baddest gospel choirs I have ever heard … and they run riffs just like any other person I know,” she said.

Some focus group participants who do not attend predominantly Black churches also expressed reservations about them.

“I don’t believe in ‘Black church.’ I believe in the church. Like, Black church is … a racial thing. I don’t believe in Black church. I mean, Black people live in this community, maybe there’s a church in that community, … but it’s still the church, not a Black church.”

– Reginald

“I wanted to just say this, that I know that my pastor does not evoke the Word limited to a race of people. We have multiculturalism in the church overall.”

– Yvette

More broadly, some participants expressed discomfort with describing congregations as “Black,” regardless of the race of the members, the race of the leadership, the style of worship or the denominational affiliation. They suggested that the word could, incorrectly, imply that non-Black people are neither welcome nor would be well served in those congregations.

Michael, for example, attends a house of worship affiliated with the AME Zion Church, a historically Black Protestant denomination. But, he said, “I’m not going to say that we’re ‘a Black church.’ It’s predominantly Black. But when you said that to me, that’s kind of like you saying that we go to ‘a Black church.’ But in God’s eye, he don’t care what color you are, as long as you go.”

Dee, who previously in the conversation had championed the value of Black churches for Black Americans, also pushed back against the idea that race is central to what they offer or that they should be defined by race. “At the end of the day … we’re all still human,” she said.

Monica, who had also spoken about the importance of majority-Black churches to her and to Black Americans more broadly, added: “Church has no color to me, because anyone’s invited to come there, whether they’re Black, whether they’re Chinese, Spanish or whatever. It just so happens that the majority of the ones that come are of Black origin. That’s about it.”

Destiny said she also attends a majority-Black congregation, but she emphasized that it is completely open to people of other races.

“Mostly Blacks attend, but it’s a mixture of Blacks, Hispanics, Mexicans. Whoever wants to hear the Word, we don’t turn them away. You’re more than welcome. We open the doors – come in! We just want you to want to hear the Word, to want to change your life. So when it comes to judging people like, ‘Oh, well, you’re not Black, so you can’t come here’ – no, we cannot do that.”

The ambivalence expressed in the focus groups over what to think about Black churches calls to mind a famous interview on Meet the Press with the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in 1960. When the interviewer asked how many White people were members of his church, King replied: none. The interviewer challenged that as a contradiction to the spirit of integration. Here’s how King responded:

“I think it is one of the tragedies of our nation, one of the shameful tragedies, that 11 o’clock on Sunday morning is one of the most segregated hours, if not the most segregated hours, in Christian America. I definitely think the Christian church should be integrated, and any church that stands against integration and that has a segregated body is standing against the spirit and the teachings of Jesus Christ, and it fails to be a true witness.”

That’s the best-known part of his answer. But shortly after that, King made an important but less well-known point. “My church is not a segregating church,” he said. “It’s segregated, but not segregating. It would welcome White members.”

In the focus groups, convened nearly six decades after King’s interview, many participants who go to Black congregations made the same distinction: Their churches are effectively segregated, but they are not deliberately segregating. They are open to – and widely desire – greater diversity in their congregations.