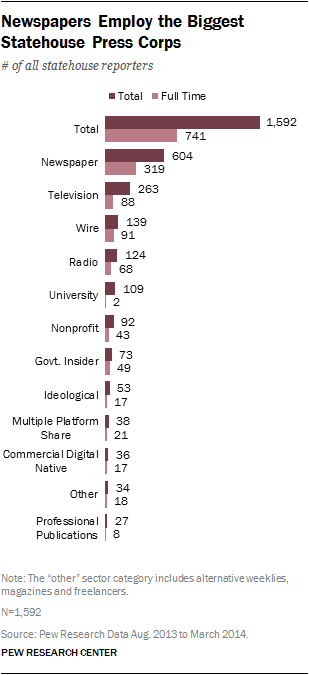

These 1,592 reporters come from a wide range of outlets and sectors. Even with the declines of the last decade, newspapers still employ the greatest portion of all statehouse reporters—38% of the total.

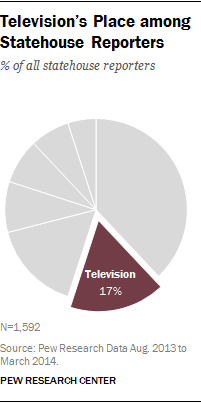

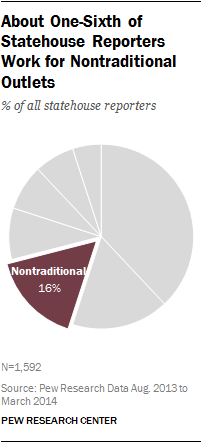

The next largest employer, television stations, account for less than half as many (17%). They are followed by reporters working for a range of nontraditional outlets such as commercial digital sites, nonprofits, specialty outlets and ideological news sites that together make up 16% of the overall reporter pool.

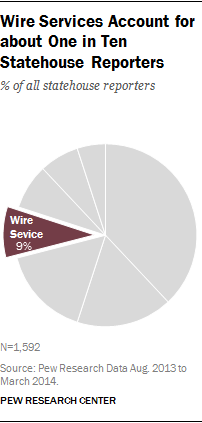

Wire services account for 9% of the total pool and radio 8%.

But it’s perhaps more instructive to look at the organizations supporting the 741 full-time reporters, which represents a greater commitment to ongoing reporting of statehouse issues and events.

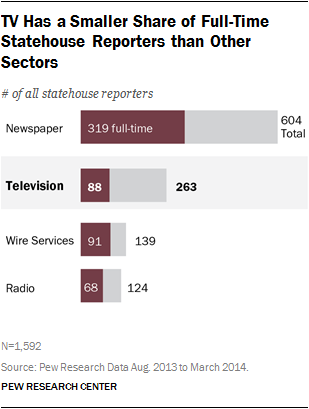

The Full-Time Reporter Pool Of the 741 journalists who cover the statehouse full time, 319 (43% of the full-time workforce) report for newspapers.

The second largest group of full-time statehouse reporters works for wire services, primarily for the Associated Press but also others such as Reuters and Bloomberg News. About two-thirds of wire service statehouse reporters (91 in all) are full time. And although they represent a modest 12% of all full-time statehouse reporters, their impact is likely greater as their stories often run in many media outlets that are wire service clients.

Television stations employ a smaller portion of all full-time reporters than they do of the total reporter pool: just 12%, or 88 full-time reporters in all, and 17% of total statehouse reporters. An additional 68 full-time statehouse reporters were assigned there by radio outlets, and 21 other full-time reporters file stories for multi-platform companies that ask them to produce stories across television, radio and print.

In addition to the legacy news organizations listed above, a number of nontraditional outlets cover statehouse news. Many of them were launched in the past six years in response to the sharp reduction of statehouse coverage by more established outlets. Taken together, the nontraditional organizations identified by Pew Research employ 126 full-time statehouse reporters, or 17% of the full-time total.

That figure includes 49 full-time reporters who work for government insider publications. These publications are aimed at those whose business interests are closely tied to state legislative activities, and they can sometimes come with a steep subscription price. Nonprofit news organizations, a growing part of the journalism ecosystem, employ 43 full-time statehouse reporters. A group of ideological news organizations, with clearly stated editorial philosophies, employ 17 full-time statehouse reporters. And another 17 full-time reporters work for a group of commercial, for profit digital native news outlets.

In addition, eight full-time journalists work for professional publications, such as local business journals or others that target a specific industry. Two full-time statehouse reporters work for outlets owned by universities—one each at the University of Illinois and the University of Missouri.

Finally, 18 full-time statehouse journalists work for outlets that we included in an “other category.” Some of them are freelancers whose work appears in a variety of outlets, while others work for outlets such as monthly magazines and alternative weeklies.

Below is a deeper look at the reporters coming from each sector of media.

Newspapers: The Primary but Declining Pool of Reporters

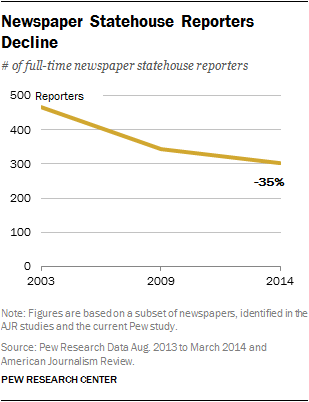

Newspapers account for the greatest portion of statehouse reporters, but to get a sense of how those numbers have declined over time, Pew Research turned to earlier studies conducted by American Journalism Review. The magazine conducted five studies of newspapers’ statehouse staffing levels between 1998 and 2009. Each time, it reported that staffing was down, with the sharpest decline occurring from 2003 to 2009.

Pew Research data show that the decline has continued in the past five years, albeit at a somewhat slower pace.

In order to provide a direct comparison with today, Pew researchers examined staffing at the papers included in both 2003 and 2009 AJR studies as well as in the current 2014 data. Those 220 papers had 467 full-time statehouse reporters in 2003, which dropped to 343 in 2009 and then to 303 in 2014. That amounts to a 27% decline from 2003 to 2009, a 12% loss from 2009 to 2014, and an overall decline of 35%. 3

These cutbacks are not uniform across the board, however. Newspapers’ statehouse staffing among this cohort of papers dwindled in 23 states between 2009 and 2014. The sharpest cuts occurred in Illinois, which lost seven full-time newspaper slots—from 12 to five—during that period. And, two of the three most populous states—California and New York—reported losses of five full-time jobs each.

At the same time, 15 states did not show any change in the number of full-time newspaper reporters covering the statehouse between 2009 and this year, though one—South Dakota—did not have any to begin with. And 12 states posted increases—most of them small. The most significant growth occurred in New Mexico and New Jersey, each of which added three reporters. (In the case of New Mexico, that doubled the staffing from three to six.) Georgia, Idaho and Massachusetts gained two reporters each. Again, this comparison was of a subset of the papers that were a part of the 2009 AJR study.

In addition to the AJR cohort, however, our current research identified 15 papers that employed 19 full-time reporters, bringing the total number of newspaper reporters currently dedicated to the statehouse full time to 319.4

To bolster the coverage provided by full-time statehouse journalists, newspapers send 285 other reporters to their capitols at various times. Of those, 55 cover state government during legislative sessions only and 144 are part time. An additional 66 reporters are students and 20 are non-student interns and others that papers did not categorize.

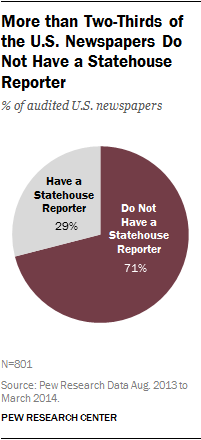

Still, a large majority of newspapers do not send anyone to the statehouse. Of the 801 newspapers nationwide that submit to regular circulation audits by the Alliance for Audited Media, almost three-quarters (71%) have no full- or part-time reporters at the statehouse. Only 229 have at least one statehouse reporter.

With the exception of USA Today—a national newspaper not anchored to any one state—each of the country’s 25 largest newspapers has at least one full-time or part-time statehouse reporter.

At one point, observers say, smaller papers had a larger presence in the nation’s statehouses.

“Way back in the day, 35 years ago, a lot of the small papers had reporters in the statehouse,” said Susan Moeller, news editor of the Cape Cod Times in Massachusetts. Her paper had a two-person statehouse bureau, which was cut to one and then zero during the recession, she said.

“You can lay off your statehouse reporter or you can lay off somebody covering your town that is nearer and dearer to people’s hearts,” Moeller said. “You will lay off the statehouse reporter because you can get that from another source.” Last year, Moeller said, editors hired a reporter to cover the statehouse part time—but he is based in Cape Cod and also responsible for covering the town of Hyannis.

Wire Services

Wire services devote a greater proportion of their statehouse staffs to the beat on a full-time year-round basis than do newspapers or broadcast outlets. Fully two-thirds of their statehouse reporters, 91 out of 139, are assigned to capitols full time.

In addition, wire services send 26 reporters to statehouses only during legislative sessions and 16 on a part-time basis. They complete their staffs with three students and three other journalists.

In all, wire service reporters represent 9% of all statehouse reporters and 12% of all full-time statehouse reporters, but their impact is greater as their work is widely distributed by other outlets that carry those stories. In interviews, several editors say that now that they have cut their own staff, they rely on wire services more than in the past.

“We receive several wire service reports, but no longer have a reporter in Springfield,” said Philip Angelo, senior editor of the Small Newspaper Group, which has a handful of papers in Illinois. “We’ve had several rounds of layoffs.”

About three-fourths (76%) of the full-time wire service reporters (69) work for the Associated Press. Other wire services with state government reporters include two national organizations, Bloomberg News, which has 12 full- and part-time reporters in 11 state capitols, and Reuters, which has one reporter in California alone. There also are several smaller wire services that distribute stories to clients within an individual state. One of those wires, the News Service of Florida, has six full-time, year-round statehouse reporters, more than any other bureau in Tallahassee.

“At the very core of the AP’s core business is state coverage, and at the very core of that is statehouse coverage,” said Brian Carovillano, AP’s managing editor for U.S. news.

Nonetheless, reporters for the AP and other outlets in a number of statehouses said the wire service cut staff during the recession. “As each person left, they never replaced them,” said Amy Worden, the Philadelphia Inquirer’s Harrisburg bureau chief and president of the Pennsylvania Legislative Correspondents’ Association. The AP’s bureau in Pennsylvania’s capitol has dropped from five reporters to three.

The AP declined to enumerate its current or past statehouse reporting staffs. However, Carovillano said: “The AP, like so many news organizations, got a little bit smaller after 2008. There was never a conscious pullback.”

With the improvement of the economy and under the guidance of Gary Pruitt, who became AP’s president and CEO in July 2012, the AP Board of Directors identified state news, in general, and statehouse coverage, in particular, as “a major priority” for 2014, Carovillano said. As a result, he added, “we are hiring a number of political and state government reporters this year.”

The Associated Press also relies more heavily upon temporary reinforcements than organizations in other sectors. While roughly two-thirds (66%) of the AP’s statehouse reporters cover the government full time, their work is supplemented by temporary reporters hired specifically to work full time or part time only during legislative sessions. This is different from the practice of newspapers, which often dispatch reporters to cover statehouses during legislative sessions, but assign them to do other things the rest of the year.

Television

Of the 918 local television stations identified by BIA/Kelsey and Nielsen, only 130 assigned at least one reporter to cover the statehouse—meaning that 86% of the local stations do not have a state government reporter.

Altogether, 263 television journalists play a role in statehouse coverage, which amounts to 17% of all statehouse reporters.

A total of 88 television reporters cover state capitols full time. An additional 28 television reporters cover statehouses only when their legislatures are in session.

The largest group of television reporters—102—cover state government part time. These often are general assignment reporters who are dispatched to the capitol to cover breaking news. In addition, television stations use 21 student reporters and 24 people who don’t fall into the other categories, but who tend to be videographers.

Nationwide, 32 states have at least one full-time television reporter covering the statehouse. Idaho, one of the smallest states with roughly 1.5 million residents, has the greatest per capita representation of television outlets in its statehouse—six stations cover the capitol in Boise. Television reporters are entirely absent from statehouses in Connecticut, Maine, Oklahoma and Oregon. Yet previous Pew studies show that local television is the primary place Americans go for news.

“A lot of people still get their news from TV and they’re not here,” said Stephen Miskin, spokesman for the Pennsylvania House Republican Caucus and for the speaker and majority leader.

Public television affiliates staff their statehouse bureaus at a somewhat higher rate than commercial broadcast stations. Ten of the 130 stations that cover state government are public TV affiliates. They employ a total of 11 full-time statehouse reporters. These outlets rarely have nightly newscasts, but produce long-form programming that tackles state issues in depth. Washington state’s PBS affiliates produce a trio of programs: “Inside Olympia,” a year-round broadcast featuring interviews with lawmakers; “The Impact,” a newsmagazine show on the statehouse; and “Legislative Review,” a daily recap of lawmaking highlights when the body is in session. In some cases, officials said these broadcasts were created in response to a reduction in reporting by other legacy outlets.

Some state-owned TV stations, such as those in California, Rhode Island and Washington—also broadcast legislative proceedings (similar to what C-SPAN does for Congress). And Pew Research identified seven states that have cable channels or local access channels dedicated to live coverage of the legislature. In some cases, these broadcasts also extend to committee hearings. Some of these channels are independent, while others are extensions of state government. Several journalists interviewed by Pew Research said that these broadcasts enable them to cover the capitol remotely.

Radio

Radio reporters constitute a smaller segment of the statehouse press corps than their television counterparts, about 8% of all statehouse reporters and 9% of those who cover the statehouse full time.

In all, radio stations assign 124 reporters to the statehouse beat: 68 who are full-time, 15 who cover it only during legislative sessions, 31 part time, 7 students and 3 who fall into none of those categories.

Reporters for public radio stations make up a just under half of both the full-time radio contingent working in the nation’s statehouses—31 of the 67. (In addition, 36 report for commercial radio outlets.) They also account for just under half of less than full-time reporters—26 of the 56.

Nontraditional Players in the Statehouse Press Corps

As legacy news organizations have reduced the size of their statehouse reporting staffs in recent years, nontraditional outlets have sprung up to try to fill the gaps in coverage.

These organizations, which are mostly digital-only, fall into four main categories: nonprofit, government insider or those aimed at government insiders, ideological and for- profit (or commercial digital native). Some news outlets fall into more than one category, particularly those that are nonprofits and also have a stated ideological bent. In those cases, we categorized them as ideological and removed them from the remaining category so as not to count any organization twice.

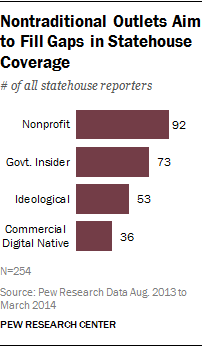

Altogether, nontraditional organizations assign 254 journalists to statehouses, accounting for 16% of all statehouse reporters. That figure comprise 126 full-timers, 28 reporters who cover state government only during legislative sessions, 73 who are on the beat part time, 21 students and 6 who fall into the “other” category.

In seven states—Connecticut, Michigan, New York, Ohio, Tennessee, Texas and Vermont—the outlet with the largest number of full-time statehouse reporters is one of these upstarts.

“We saw the need. There’s been a decline in state coverage here as elsewhere. We felt that there was an underserved market for it,” said Joe Copeland, political editor for Crosscut, a Washington state website that launched in 2007 and started covering the statehouse full time last year.

According to the AJR census, the largest reduction in newspaper statehouse reporters coincided with historic decreases in total staffing during the recession, though it was underway in the three preceding years. As reporters were laid off or bought out, some of these journalists—who had covered state government for legacy outlets—decided to start their own news organizations or to buy and transform existing ones.

“When we started, everybody was abandoning their state capitol desk at the time. There was this mass exodus,” said Christine Stuart, editor in chief of CTNewsJunkie.com. Stuart bought the for-profit Connecticut website in 2006, the year after it was founded. “We were really filling a gap that existed. The mainstream media had abandoned statehouse reporting.”

Commercial Digital Native

Eleven for-profit websites cover state government with 36 reporters, 17 of whom are on the beat full time. Nine of the outlets were founded in the past decade, including seven during or after 2008.

The for-profit site that has the greatest number of full-time, year-round statehouse reporters is the four-year-old Capital New York, which has the largest bureau in Albany. With five full-time journalists and one student intern covering the statehouse, Capital New York eclipses the New York Times and the Albany Times Union, each of which has three full-time reporters and none in any other category. None of the 24 other outlets that cover state government in the third most populous state has more than two full-time, year-round reporters in the capitol.

In fact, only 10 other news organizations in the country—of any type—have more than five full-time journalists in their statehouse bureaus year-round. And many of the for-profit outlets are not as large as Capital New York.

Erik Smith, news editor of the Washington State Wire, is the lone journalist for a site that provides a combination of original reporting and aggregation. A former statehouse reporter for two newspapers, Smith founded his outlet in 2003, just as other state government reporters were losing their jobs. Now, he said, he is struggling to find a way to sustain the site financially, and might seek nonprofit status.

Not all the outlets were created recently. Brian Howey, publisher of Howey Politics Indiana, formed his organization in 1994 as the Howey Political Report and put most of it online in 2001. A former newspaper reporter, Howey oversees a website, with some free and some subscription-only content, and a weekly print publication, which he mails to subscribers. He also writes a column that he syndicates to 30 newspapers in the state. His publication, which is edited by his journalist parents, has one full- time, year-round statehouse reporter and two part-timers.

[and]

Nonprofits

Like for-profit digital news organizations, nonprofit outlets have mushroomed since the recession pummeled the legacy news industry. Last year, Pew Research identified 172 nonprofit news outlets across the country. Our new study found that 23 of the nonprofits that were not also ideological cover state government.

The nonprofits have a relatively small number of reporters in capitols, just 43 full time and 92 in total—6% of all statehouse reporters. In addition, five reporters cover the statehouse during legislative sessions and 26 do so part time. Fifteen of the nonprofit reporters are college students, and three fall into the “other” category.

The Texas Observer has been covering the statehouse in Austin for 60 years, but that is an outlier in terms of age. Sixteen of the nonprofits that report on statehouses were founded in the past six years. In addition to the Texas Observer, only one—the Center for Investigative Reporting, which dates back to 1977—existed before 2000. St. Louis Public Radio, an affiliate of National Public Radio, also has existed for some time, but it merged with the newer, digital-only St. Louis Beacon in December 2013 to create a new entity.

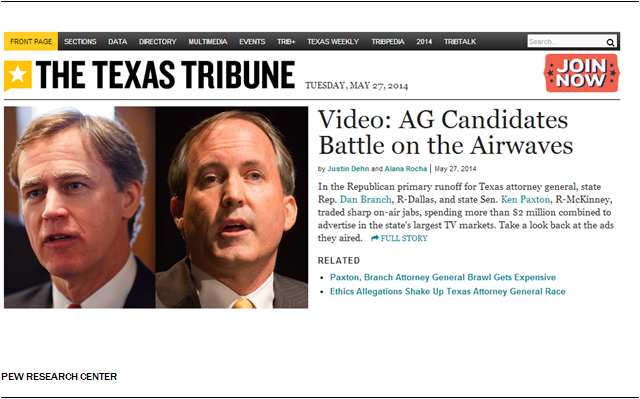

Most nonprofits employ few reporters, but some have bigger staffs. The Texas Tribune has the largest statehouse bureau of any news organization in the country, with 15 full-time, year-round reporters and 10 students. The Connecticut Mirror is next with four full-time reporters.

The Texas Observer has three full-time, year-round statehouse reporters and three students. VTDigger.com also has three full-time statehouse reporters—representing nearly one-quarter of all full-time reporters in Vermont’s capitol. Four other nonprofits have two full-time statehouse reporters.

Ideological Organizations

Among the nontraditional statehouse outlets are those that have a stated ideological point of view. Most of them define themselves as conservative or as in favor of a “free market,” a basic tenet of economic conservatism. Only one outlet, NC Policy Watch, calls itself progressive.

The ideological outlets assign 53 reporters to the statehouse. Those outlets assign 17 reporters to state government full time, just 2% of all full-time reporters. They dispatch 15 reporters to the statehouse only during legislative sessions and 19 are part time. In addition, they have two student reporters. Most of these publications are digital only and many also are nonprofits. But because they describe themselves in ideological terms, we created a category to distinguish them.

About half of the ideological sites (14 out of 33) are owned by the Franklin Center for Government & Public Integrity, a nonprofit that was founded in 2009 “to address the falloff in statehouse reporting as well as the steep decline in investigative reporting in the country,” said spokesman Michael Moroney. The center, based just outside Washington, D.C., in Alexandria, Va., supports a free market, he said.

In a 2011 study of news nonprofits, Pew Research found that the Franklin Center’s Watchdog.org sites were about four times as likely to present stories with a conservative theme than with a liberal one, though about half (49%) of their stories either had no ideological theme or had a combination of them. Its president, Jason Stverak, is a former executive director of the North Dakota Republican Party.

The Franklin Center places reporters in state capitols full time when legislatures are in session and assigns them to work on investigative projects the rest of the year, Moroney said. He said there is one reporter in each of 14 state capitols and two in Nebraska and Virginia. In addition to posting the stories on Franklin Center websites, the organization syndicates them. That is a nod to the enduring dominance of more established news outlets, particularly newspapers.

“We know that the best way to get those stories out there is through the legacy media,” Moroney said.

Representatives of some of the conservative outlets say they are acting as an antidote to what they see as liberal bias in the mainstream media.

“Our feeling was in Tallahassee and many other statehouses, there really wasn’t anybody who was looking at the other side of the story,” said Nancy Smith, executive editor of Sunshine State News, which she described as “right of center.” “They look at a more liberal side of the news—almost everybody up there does.”

Sunshine State News was founded in 2010 with investments by “three people who want to see the other side of the news covered,” Smith added. The organization does not divulge their identities, she said. Smith, like a number of other journalists at outlets with known ideologies, hails from the legacy media. She was an editor at The Stuart News/Port St. Lucie News for 28 years and is former president of the Florida Society of Newspaper Editors.

NC Policy Watch identifies itself on its website as a “progressive, nonprofit and non-partisan public policy organization and news outlet.” It is an independent project of the NC Justice Center, a nonprofit anti-poverty organization.

The fact that ideological organizations have begun to put reporters in statehouses has not gone unnoticed by legacy journalists.

“Some of the vacuum has been filled by advocacy groups,” said Rob Christensen, longtime statehouse reporter for the News & Observer in North Carolina. “Of course, they all have axes to grind, but they do provide information.”

Government Insider Outlets

A total of 73 reporters cover state government for specialty publications aimed at government insiders, and 49 of them are full time—accounting for 7% of the total full-time statehouse reporting corps. Five reporters cover the statehouse only during legislative sessions, and 15 do so part time. Two of the journalists are students and two are in the category of “other.”

These outlets often charge hefty subscription fees, placing the content outside the reach of a general audience. They target lawmakers, lobbyists, activists and even journalists who are willing to pay for highly specialized information about the inner workings of government. Indeed, some of these outlets are owned by lobbyists or interest groups.

Prices for these outlets vary widely. The Alaska Budget Report charges $2,397 a year, the Austin Monitor $1,099 a year and the Tennessee Journal, $247 a year, to name a few. Conversely, StatehouseReport.com/ CharlestonCurrents.com is free.

Most of these organizations track legislative bills and cover many of the small-bore daily developments of government—such as the incremental progression of a bill or a committee hearing—that general-interest outlets tend to ignore.

The Florida Current, which says on its website that it “is written for stakeholders in Florida’s legislative process,” is one of the rare insider outlets that does not charge a fee to readers. It is owned by Lobby Tools, an online subscription service that provides legislative research and analysis, bill tracking and customized daily reports. The Current’s managing editor and three reporters formerly worked at legacy outlets, according to the organizations’ website.

The rise of niche outlets that have stepped in to cover statehouses as the legacy press corps shrunk follows a pattern found in coverage of the U.S. federal government. In an earlier report on the composition of the Washington press corps, Pew Research identified a dramatic rise in specialty publications at the same time that mainstream media coverage of Washington was declining.