Most health seekers are searching on behalf of someone else.

Three different groups of Internet users emerge as noteworthy health seekers: those who use look for health information on behalf of others; those with disabilities; and those who care for others full time.

Most health seekers are searching on behalf of someone else.

A significant 57% of health seekers said the last time they did a health search, they looked for information for someone else. This group is heavily represented by parents, women, healthy people, and the middle aged between 30 and 49 years old.

Parents are more likely than non-parents to have dedicated their last health search to someone else – 65% vs. 50%. Women are more likely than men to say their latest search was at least in part for someone else – 62% compared to 50% of men. Not surprisingly, the characteristic most likely to define a health seeker on behalf of others is the good health of the user: 59% of healthy Internet users look on behalf of others, compared to 32% of those in poor health themselves. And 62% of 30-49 year-olds did research for someone else the last time, compared to 38% of Internet users aged 65 and over.

Women who describe their health as “good” or “excellent” are the most likely Internet users to search on behalf of someone else – 66% have done so, compared to 59% of men in good health.

From our online survey, we discovered a range of reasons why health seekers go online on behalf of others. Among the most important reasons is to get care-giving guidance. For example, one woman wrote about how she used the Internet to span the miles between family members, sharing what she found about end-of-life care. “My father died in January 2002 of lung cancer. My siblings and I are spread across the country and took turns flying to Florida to care for him. Through the Internet I was able to research Hospice and determine that my father was eligible. I asked his doctor to recommend it (none of his many doctors mentioned it to my family). Unfortunately my father was cared for by Hospice for only two weeks before his death.”

[I]

Some e-patients use their newfound awareness of health resources to advocate for loved ones, accompanying them to doctor’s appointments and connecting them to other people with the same diagnosis. One person wrote, “Being informed makes it easier for me to be of support to my family and friends in a time of need.” Another wrote that online health information helped alleviate some of her husband’s concerns about cancer surgery. “It helped him to be prepared for a new way of life,” she wrote. “He has also benefited from pointers from others who deal with the same concerns.”

Mark Bard of the Manhattan Research Group has coined a term that captures this “searching for someone else” phenomenon. He writes that, when counting the millions of Americans who actively use online health resources, researchers should calculate a much larger “zone of influence”28 made up of friends, family members, co-workers, and neighbors who also benefit from e-patients’ searches. Health care is often a highly social pursuit, not a solitary activity. It is essential to reflect this reality when researching, serving, or creating policies for the health seeker population.

Health seekers who live with a chronic illness or disability actively use the Internet, despite many obstacles.

A second group that emerged from our data is the small group of Internet users who are living with a disability, handicap, or chronic disease.

Fifteen percent of Americans report in our survey that a disability, handicap, or chronic disease keeps them from participating fully in work, school, housework, or other activities. The likelihood of disability and chronic illness increases with age: 5% of 18 – 29 year-olds live with a disability or chronic illness, and the rate increases with age to 28% of Americans over 65 years old.

Americans living with a disability have among the lowest levels of Internet access in the country. In a survey in the spring of 2002, we found that 38% of Americans with disabilities go online, compared to 58% of all Americans. Of those with disabilities who do go online, a fifth say their disability makes using the Internet difficult. Disabled non-users often face large hurdles in relation to the Internet: They are less likely than other non-users to believe that they will ever use the Internet and less likely than others to live physically and socially close to the Internet. Americans living with a disability are also less likely to have friends or family who go online.

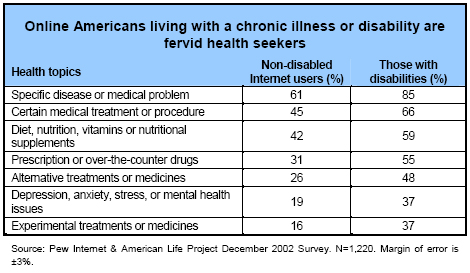

Those who do go online are very active users: Eighty-seven percent of disabled or chronically ill Internet users have searched for at least one health topic. Nearly every topic we asked about was more popular with disabled or chronically ill Internet users than with the rest of the Internet population.

Similarly, disabled or chronically ill users are avid online communicators. They are significantly more likely to exchange health-related email with friends – 34%, compared to 20% of non-disabled, healthy email users. The two groups are equally likely to use email to communicate about health issues with family members – about 23%. One in five disabled or chronically ill email users have exchanged email with a doctor, far surpassing non-disabled, healthy users: 19% vs. 6%.

Home caregivers focus on more urgent concerns, such as treatments, procedures, or drugs.

A third group that emerged from our data are those who take care of someone living in their household – 11% of Americans live with someone chronically ill or disabled and 70% of that group is a primary or secondary caregiver. Six million home caregivers go online and, when looking for health information, tend to focus on imperatives like treatments, procedures, or drugs.

“Home caregiver” – Respondents were first asked if any member of their household has a disability, handicap, or chronic disease that keeps them from participating fully in work, school, housework or other activities. If they answered yes, respondents were asked if they are responsible for this person’s care.

Wired home caregivers are more likely than the general Internet user population to have searched for information about a specific medical treatment or procedure (62% vs. 47%) and for information about prescription or over the counter drugs (55% vs. 34%). They are also more likely than the general Internet population to have researched mental health information (37% vs. 21%), experimental treatments (35% vs. 18%), and Medicare or Medicaid (21% vs. 9%). Caregivers are, in general, avid online health researchers – they are just as likely as non-caregivers to have searched for all the other topics we asked about.

Caregiving duties are more likely to fall to older generations than to Americans under 30. Just 15% of 18-29 year-olds who live with a care recipient say they are primarily responsible for the disabled loved one, compared to about 60% of Americans over the age of 30 who are living with a care recipient.

About half of home caregivers are Internet users, and their lengths of experience reflect the general Internet user population, but they are more likely to have dropped off the Internet for a time. Caregivers are more likely than the rest of the Internet population to go online only from home, possibly because they tend to work somewhat less and perhaps spend more time at home.

Family caregivers probably all have extraordinary stories to share about the good days and the bad days, the lucky breaks and the near-misses, but there is one who stands out in our online survey. She cares for her husband at home, researching each medication before he begins a new prescription and tracking his many health concerns. She is a newcomer to the Internet, but has clearly jumped in with both feet. As she relates, “Hubby has special high rise alternating air pressure mattress. Last year there was a power surge that blew out the motor. This mattress is very important, not only for skin care but his breathing also. Company that originally supplied us with setup no longer dealt in them (Medicaid/Medicare no longer would pay for them). They gave me info to contact company but neither could supply back up motor and this happened two days before Christmas so the repair would take at least a couple of weeks. I went online to eBay and found a used motor at auction for a very reasonable price, reasonable enough so that I could have it sent overnight. Saved the holiday, saved hubby from potential problems and we have a back up in the house should we ever have another problem.”