Social hostilities around the world involving religion declined in 2019 to the lowest level in five years, while government restrictions on religion remained at a peak, according to Pew Research Center’s 12th annual global study of restrictions on religion.

The Center’s study analyzes 198 countries and territories and is based on policies and events in 2019, the most recent year for which data is available – covering incidents before the disruptions of the coronavirus pandemic.

Social hostilities can range from harassment over a person’s religious identity to religion-related mob violence, sectarian conflict and terrorism. Government restrictions include laws, policies and official actions that infringe on the religious beliefs and practices of groups or individuals within a country.

Some of the incidents recorded in this study are tied to ongoing hostilities, such as the detention of Uyghur Muslims in China, the displacement of Rohingya Muslims from Myanmar (also known as Burma), and attacks by groups such as ISIS and its affiliates in the Middle East-North Africa and other regions.

These are the key findings from the report.

This post is based on the 12th annual Pew Research Center report on the extent to which governments and societies around the world impinge on religious beliefs and practices. The studies are part of the Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures project, which analyzes religious change and its impact on societies around the world.

To measure global restrictions on religion in 2019, the most recent year for which data is available, the study rates 198 countries and territories by their levels of government restrictions on religion and social hostilities involving religion. The new study is based on the same 10-point indexes used in the previous studies.

- The Government Restrictions Index (GRI) measures government laws, policies and actions that restrict religious beliefs and practices. The GRI comprises 20 measures of restrictions, including efforts by governments to ban particular faiths, prohibit conversion, limit preaching or give preferential treatment to one or more religious groups.

- The Social Hostilities Index (SHI) measures acts of religious hostility by private individuals, organizations or groups in society. This includes religion-related armed conflict or terrorism, mob or sectarian violence, harassment over attire for religious reasons and other forms of religion-related intimidation or abuse. The SHI includes 13 measures of social hostilities.

To track these indicators of government restrictions and social hostilities, researchers combed through more than a dozen publicly available, widely cited sources of information, including the U.S. Department of State’s annual reports on international religious freedom and annual reports from the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom, as well as reports and databases from a variety of European and United Nations bodies and several independent, nongovernmental organizations. (Read the methodology for more details on sources used in the study.)

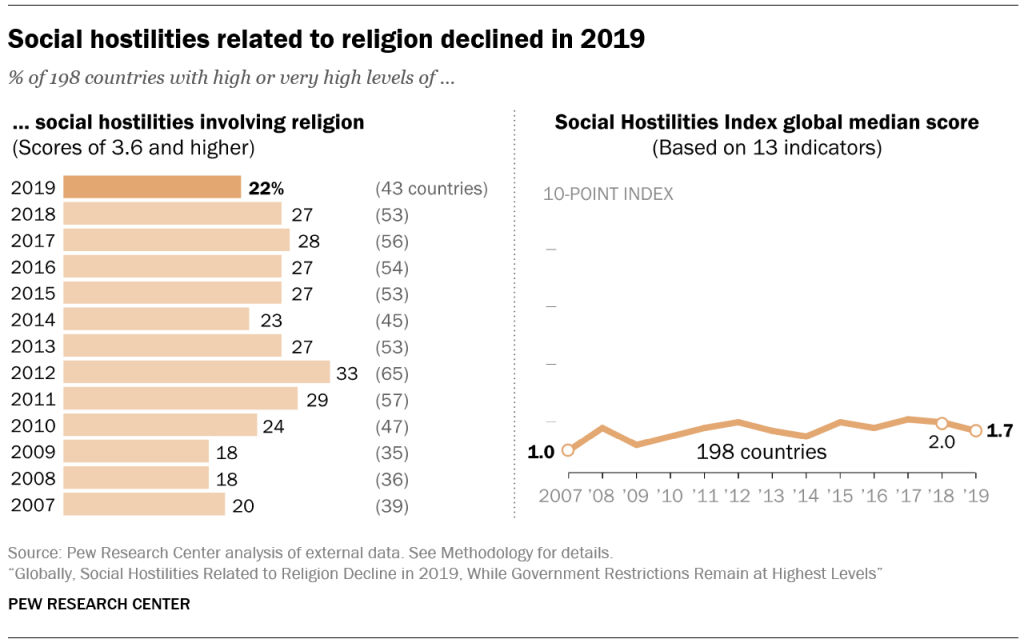

Social hostilities tied to religion fell in 2019, partly due to a decrease in reports of terrorism, mob violence and hostilities against proselytizing. The median score among all countries on the Social Hostilities Index (SHI) dropped from 2.0 in 2018 to 1.7, the lowest level since 2014. The SHI is a 10-point scale based on 13 indicators, such as hostilities due to a person’s religious identity. Meanwhile, the number of countries with “high” or “very high” levels of social hostilities fell from 53 (or 27% of the countries in the study) in 2018 to 43 (or 22%) in 2019, the lowest number in 10 years.

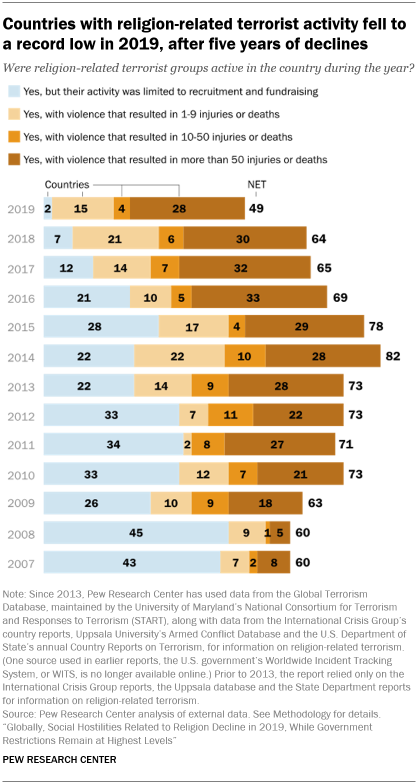

Religion-related terrorism fell for a fifth consecutive year, pushing the number of countries experiencing such events to a record low for the study. In 2019, 49 countries experienced religion-related terrorism, down from 64 countries in 2018 – a substantial decline from the peak of 82 countries in 2014. This measure includes actions by terrorist groups that led to property damage, detention, displacement, physical injuries or deaths. It also includes recruitment and fundraising activities by these groups.

Four of the five regions analyzed in the study experienced a drop in religion-related terrorism: the Americas, the Asia-Pacific region, Europe and the Middle East-North Africa region. In Iraq, for example, the number of violent attacks by the armed group ISIS decreased in 2019, and the group lost a large swath of territory in both Iraq and Syria.

Still, ISIS continued to inspire attacks in some parts of the world. Groups pledging allegiance to ISIS carried out bombings in Sri Lanka on Easter Sunday, 2019, killing more than 250 people and injuring approximately 500 others.

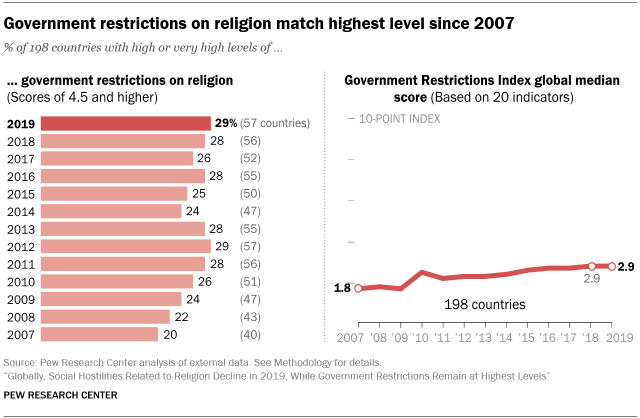

Government restrictions, such as interference in worship, stayed at a record high for the study. The global median score on the Government Restrictions Index (GRI) remained at 2.9 in 2019, the highest level reached since the Center began tracking these trends in 2007. The GRI is a 10-point index based on 20 indicators, such as official actions that limit religious practices including preaching and worshiping. Meanwhile, the number of countries with “high” or “very high” levels of government restrictions ticked up from 56 in 2018 to 57 (29% of all countries analyzed) in 2019, matching the 2012 peak. In total, governments in 180 countries harassed religious groups in some way in 2019 – for example, by detaining individuals for practicing their faith – and 163 governments interfered in worship. Both are peaks for the study.

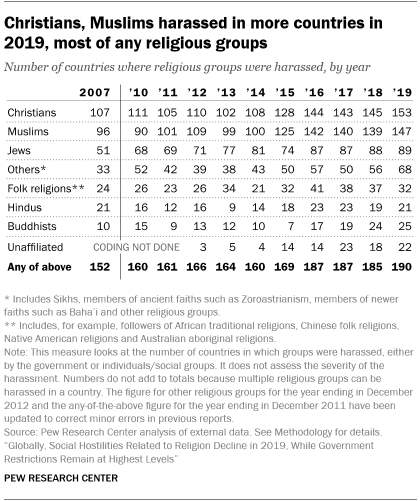

People were harassed, either by governments or social groups, in religion-related incidents in 190 countries, the highest number since the study began. Harassment can range from derogatory statements to physical acts of force such as property damage or assaults.

As in previous years, Christians and Muslims – the world’s largest and most widely dispersed religious groups – experienced harassment in more countries than other religious groups in 2019 (153 and 147 countries, respectively).

Meanwhile, Jews faced harassment in 89 countries, even though they make up a small share of the world’s population. In Belgium, for example, media reported that negative Jewish stereotypes were displayed on a float at a carnival in March.

Among the world’s 25 most populous countries, Egypt, India, Pakistan, Nigeria and Russia had the highest levels of restrictions on religion overall when considering both government restrictions and social hostilities. Although residents in the most populous countries are not equally affected by religious restrictions, the scores are worth noting given that three-quarters of the world’s population lives there. Within this group, China, Egypt, Russia, Iran and Indonesia had the highest levels of government restrictions, while India, Nigeria, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Egypt had the highest levels of social hostilities. In Indonesia, the world’s largest Muslim-majority nation, the practice of Ahmadi or Shiite Islam is banned in certain localities. The Indonesian government also continued to detain individuals for violating blasphemy laws. And in Pakistan, Ahmadi and Shiite Muslims, including people from the Hazara ethnic group, were killed in targeted attacks by nongovernmental entities throughout the year.