At Pew Research Center, we regularly field questions from readers about the methodology behind our polls, including the occasional inquiry from someone who wants to be polled but hasn’t had the opportunity. These kinds of questions are understandable since the average American likely isn’t an expert in survey methodology.

Here, we address some of the most common questions we receive about the nuts and bolts of taking a U.S.-focused Pew Research Center poll. This explainer focuses specifically on the polls we field using our American Trends Panel, a nationally representative group of roughly 10,000 U.S. adults. While we field polls in other ways, too, we rely on the panel to conduct the majority of our U.S. surveys.

This Pew Research Center article provides answers to some of the common questions we receive about the methodology behind the surveys we conduct in the United States. It focuses specifically on the methodology of the American Trends Panel, or ATP, a randomly selected, nationally representative group of U.S. adults who have agreed to take our surveys.

How can I sign up to take one of your surveys?

Unfortunately, you can’t. The Center relies on random sampling, which means we invite people to take our surveys by reaching out to them at random rather than simply polling those who ask to be polled. This helps ensure that nearly everyone in the United States has a roughly equal chance of being selected. It also increases the likelihood that our survey takers are representative of the broader population we’re trying to study – most commonly, U.S. adults ages 18 and older.

Polling only those who want to be polled would not produce a representative sample of U.S. adults, for the simple reason that “volunteers” may differ in key ways from the broader population.

How exactly do you randomly select Americans to take your surveys?

In the past, the Center called a random sample of U.S. landline and cellphone numbers to invite Americans to take a survey, an approach known as random-digit dialing. But in an era of robocalls and caller ID, many Americans no longer answer calls from unknown numbers. Response rates to telephone surveys in the U.S. have plummeted in recent decades, making it much more difficult and costly for polling organizations to reach respondents this way.

Fortunately, the widespread adoption of the internet in the U.S. has made online polling an attractive alternative to phone polling. As of 2023, 95% of U.S. adults say they use the internet, and the Center now does the vast majority of its U.S. polling online. (Scroll down for more on the 5% of adults who don’t use the internet.)

But the process of randomly inviting Americans to take our online surveys still takes place offline. That’s because there is no way to generate a comprehensive list of U.S. email addresses the way there is for U.S. phone numbers.

These days, we mostly recruit people to take our surveys by mailing them printed invitations – again at random – with the help of a residential address file kept by the U.S. Postal Service. This approach gives nearly everyone living at a U.S. residential address a chance to be surveyed (though it does exclude some people, such as those who are incarcerated or living at a rehabilitation center). We usually include a small amount of cash with each invitation to increase the chances that recipients will notice and respond to it.

Some of the people who agree to take one of our surveys may receive an additional request: an invitation to join the American Trends Panel, or ATP. This is a large group of U.S. adults who have agreed to take multiple surveys over time. As of 2024, the ATP has about 10,000 participants, but this number changes fairly regularly as we recruit new members and others stop participating.

The ATP is our main vehicle for conducting surveys in the U.S., but it is not the only one. From time to time we also conduct special surveys that use different samples. Here’s a survey of U.S. teachers, for example, and another one that focused on U.S. journalists.

How is it possible that I’ve never been randomly invited to take a survey?

It may seem counterintuitive that you’ve never been randomly selected to take a Pew Research Center survey. But keep in mind that the adult population in the U.S. exceeds 260 million people. Even with a large survey panel like the American Trends Panel, your chances of being invited to join it are exceedingly small – somewhere around 1 in 26,000.

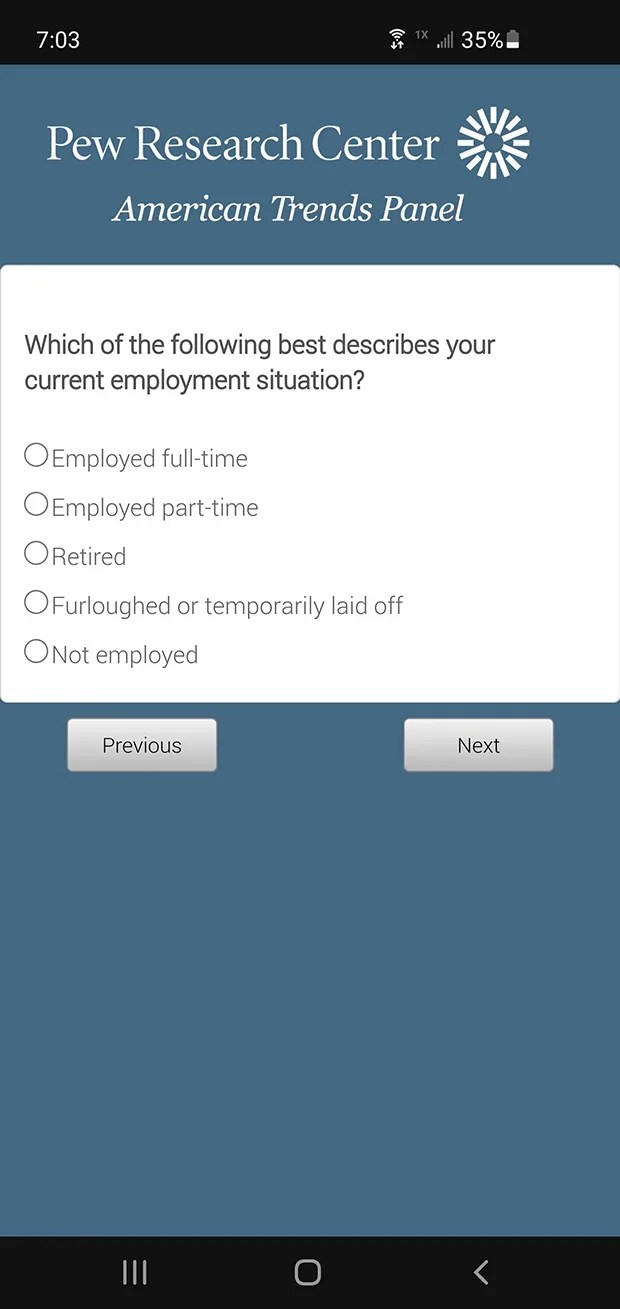

Once invited, how do people actually take your surveys?

Most participants in the American Trends Panel fill out survey questionnaires with whatever internet-enabled device they prefer, whether it’s a smartphone, tablet, laptop computer or desktop computer. The questionnaires are self-administered, meaning that respondents can fill them out whenever it’s convenient for them, so long as it’s within a window of time (usually a week or two) that we communicate to them at the outset of each survey field period.

Our ATP surveys are typically designed to take respondents an average of 15 minutes to complete online. We try to be respectful of our respondents’ time and are mindful of the fact that survey data quality can decrease if it takes people too long to answer all of our questions.

Not everyone in the U.S. uses the internet, so how can your online surveys be nationally representative?

This is a great question, and an important point. Nationally, 5% of U.S. adults don’t use the internet, according to a 2023 survey (which, for obvious reasons, we conducted by mail as well as online). Other people may have access to the internet but prefer not to take online surveys because of concerns about privacy or just a lack of comfort with computers.

While non-internet and internet-averse adults are a minority in the U.S., we can’t just ignore or overlook these Americans, so we’ve tried a variety of approaches to include them in our surveys.

In the early days of the American Trends Panel, we surveyed internet non-users by mailing them paper questionnaires with the return postage paid. Beginning in 2016, we provided them with internet-enabled tablets and data plans so they could fill out our questionnaires online, just as regular internet users would. These days, we give internet non-users the option to take our surveys by phone instead of online.

Do your surveys include people who don’t speak English?

Just as we do with internet non-users, we try hard to include non-English speakers in our polling. All of our questionnaires are available in Spanish as well as English, and 99% of adults in the U.S. speak one or both of these languages well enough to complete a survey.

Of course, people in the U.S. speak many other languages, too, and it remains a challenge to survey the small percentage of people who don’t speak English or Spanish. This is especially difficult when it comes to Asian Americans, a diverse and heavily immigrant population who have origins in more than 20 countries and speak a wide variety of languages.

The surveys we field on the American Trends Panel only include Asian Americans who speak English or Spanish. In other words, these surveys can only provide a limited view of the attitudes of the entire Asian American population. This is why you will typically see an asterisk next to the “Asian Americans” label in many of the graphics we publish about racial and ethnic differences in U.S. public attitudes. The asterisk denotes this limitation.

If the same people take your surveys over and over again, doesn’t that make them different from people who don’t take the surveys, and thus make them unrepresentative of the public?

Theoretically, yes. Asking the same people the same questions may cause them to remember their previous answers and feel pressure to answer consistently over time. Conversely, some participants in online survey panels like the American Trends Panel might change their attitudes or behaviors simply by being exposed to and answering a variety of questions over time. This is known as panel conditioning.

Consider a survey that asks about Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer. A survey respondent initially may not be familiar with Schumer; after all, many Americans don’t follow the details of Washington politics all that closely. But if a polling organization asks about Schumer in repeated surveys, it may cause the respondent to seek out more information about Schumer and, in the process, become more politically engaged than initially was the case.

Fortunately, a 2021 Pew Research Center study found little evidence that panel conditioning has changed our survey respondents’ views or behaviors in several areas where such changes might be expected, including in their media consumption habits, the frequency with which they discuss politics, their party affiliation and their voting records. But the study did find a slight increase in voter registration after people joined the American Trends Panel.

Asking the same people to take surveys over a protracted period of time has some advantages, too. For example, as panelists become more comfortable with answering questions in a self-administered online setting, they might report their opinions and behaviors more forthrightly than they otherwise would have.

Repeatedly surveying the same people also allows the Center to examine how their attitudes are or aren’t changing over time, an approach known as longitudinal research. In 2018, for example, the Center published a study looking at how opinions of then-President Donald Trump had changed (or, more accurately, had not changed) among those who voted for him in 2016.

How often do your respondents take a survey?

We typically field two or three surveys a month, but not all of our panel members take each survey. Instead, we often survey smaller groups of people in “waves.” This helps ensure that our respondents don’t get worn out by answering so many questions.

Do you pay people to take your surveys?

Yes. We provide a small token of appreciation to our panelists for completing each survey we’ve invited them to take. Respondents can choose to receive their payment in the form of a check or a gift code.

Note: This post was updated on Aug. 6, 2024, to reflect the current number of panelists on the American Trends Panel. This is an update of a post originally published on Sept. 7, 2021.