The November presidential election saw record-high turnout following a general election campaign in which large numbers of registered voters consistently reported high levels of interest in the election and its outcome. For many voters, participation in an election goes beyond voting to include activities such as publicly showing their support for a candidate, contributing money to a campaign or attending campaign events. Here are key findings on Americans’ engagement with the political campaigns in this year’s election based on Pew Research Center’s post-election survey, conducted Nov. 12-17.

To explore the level of engagement of voters in the 2020 election, Pew Research Center surveyed 11,818 U.S. adults in November 2020, including 10,399 U.S. citizens who reported having voted in the November election.

Everyone who took part in this survey is a member of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Asian respondents were interviewed only in English. Read more about the ATP’s methodology.

Here are the questions used for this report, along with responses, and its methodology.

About half of voters report engaging in a range of political activities

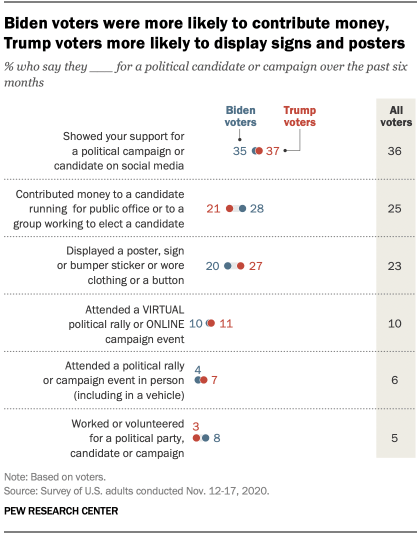

A narrow majority of U.S. adults who report having voted in the general election – 53% – say they engaged in at least one of six different political activities over the past six months, including contributing money to candidates, attending political rallies or events or working for campaigns.

More than a third (36%) say they demonstrated support for a candidate on social media. Another quarter say they contributed money to a political campaign, while about as many (23%) say they displayed a poster, sign or bumper sticker or wore clothing or a button to show their support for a candidate.

In an election campaign greatly impacted by the coronavirus outbreak, more voters (10%) say they attended a virtual political rally or online campaign event than say they attended such an event in person (6%).

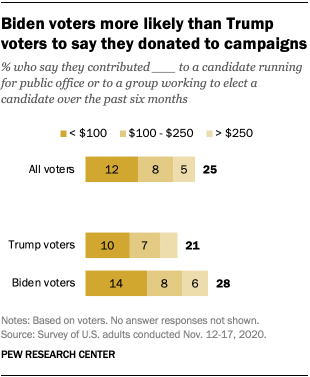

Biden voters are more likely than Trump voters to say they contributed money to candidates running for office (28% of Biden voters vs. 21% of Trump voters) or worked or volunteered for a political campaign (8% vs. 3%).

Among voters who contributed money to a campaign, about half say they gave less than $100 and about half say they gave $100 or more. Identical shares of Trump voters who contributed money and Biden voters who contributed money say they gave less than $100 (49% of both groups).

Trump voters are more likely than Biden voters to say they displayed a poster or sign or wore an item of clothing or button in support of a political campaign (27% of Trump voters vs. 20% of Biden voters). And while small shares of the supporters of each candidate say they attended a political rally or campaign event in person, 7% of Trump supporters say they attended such an event compared with 4% of Biden voters.

Campaigns still rely on printed mail to reach voters

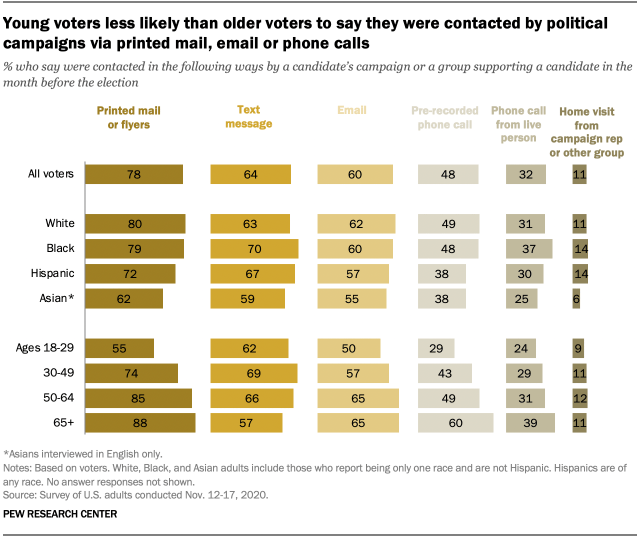

Majorities of voters say they received text messages (64%) or emails (60%) from political campaigns in the month before the presidential election. But an even larger share (78%) say they were contacted in more traditional ways, with printed mail or fliers.

Fewer voters say they were contacted by phone, either by a prerecorded call (48%) or a call from an actual person (32%). Only about one-in-ten voters (11%) say they received a home visit from a representative of a political campaign or another group.

There are only modest differences in the shares of Biden and Trump voters who report being contacted by campaigns in the month before the election. But there are wide age differences in reported campaign contacts.

Overall, voters under age 30 are less likely than older voters to say they were contacted by campaigns via printed mail, email or by phone. However, the age differences are more modest in the shares saying they received a text message from a campaign or a visit at home from a campaign representative.

Across all methods of contact, Asian voters reported receiving contact at lower levels than White, Black or Hispanic voters (with the exception of a prerecorded phone call, for which Hispanic voters report the same share). More Black and Hispanic voters received a text message or home visit than White voters, while similar shares of White voters and Black voters say they received printed mail, email or prerecorded phone calls from a campaign.

Highly engaged voters were more likely to say they were contacted by campaigns

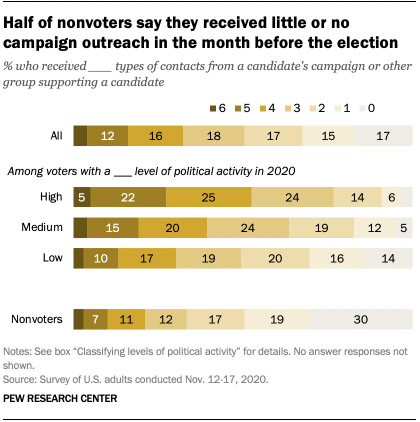

There is a strong association between a voter’s level of political activism and the amount of campaign outreach they received in the month before the election.

Voters who were more highly engaged in the campaign report that they were contacted much more often by campaigns than less engaged voters. And voters are much more likely than nonvoters to report receiving several different types of contact from political campaigns late in the presidential campaign.

Three-in-ten nonvoters say they didn’t receive any of the types of campaign communications asked about in the survey, and 20% say they received just one type of contact.

High engagement voters—those who report attending a rally or event, contributing money to a campaign, or working or volunteering for a campaign – are significantly more likely to say they received multiple types of campaign communications. More than one-quarter of these voters say they received five or more types of communications, and about half say they received four or more.

Medium engagement voters – those who publicly displayed their support for a candidate or shared that support on social media, but did not attend a rally or event, contribute money, or work or volunteer for a campaign – tend to say they received fewer types of contact than high engagement voters. And low engagement voters – those who did not participate in any of these activities – report the fewest types of contact among voters.

To classify voters’ levels of political activity, researchers created three categories.

High engagement voters are those who report participating in at least one of the following activities over the past six months: Attended a rally or event in person, attended a rally or event online, contributed money to a campaign, or worked or volunteered for a campaign. Medium engagement voters displayed their support for a candidate through a poster, sign, bumper sticker, item of clothing or button, or shared their support on social media but did not attend a rally or event, contribute money or volunteer for a campaign. Low engagement voters did not participate in any of the six activities included in the survey.

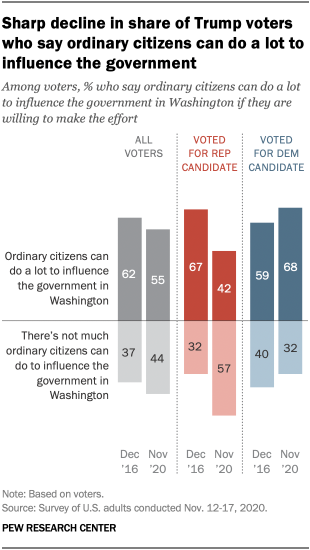

Views among voters about whether ordinary citizens can do a lot to influence the government have changed

A majority of voters (55%) say that ordinary citizens can do a lot to influence the government in Washington if they are willing to make the effort, while 44% say there’s not much ordinary citizens can do. The share who say ordinary citizens can do a lot is down slightly compared December 2016, when 62% of voters said this.

While overall opinion has changed little since 2016, there has been a sharp decline in the share of Trump voters who say ordinary citizens can do a lot to influence government, from 67% four years ago to 42% today.

By contrast, 68% of Biden voters say ordinary citizens can do a lot to influence government, up modestly from the 59% of Hillary Clinton supporters who said this in December 2016.

Note: Here are the questions used for this report, along with responses, and its methodology.