Politically, Greece has long been aligned with the West. It joined NATO in 1952 and the European Union in 1981, and, unlike nearly all its neighbors in southeastern Europe, it remained outside the Soviet sphere of influence during the Cold War.

When it comes to public attitudes on religion, national identity and the place of religious minorities, Greeks, like their neighbors to the East, hold more nationalist and less accepting views than do Western Europeans, according to a new Pew Research Center analysis of surveys in 34 countries across the continent. Greeks appear to recognize this: Seven-in-ten agree with the statement, “There is a conflict between our country’s traditional values and those of the West.” And a majority of Greeks hold at least some affinity toward Russia: Seven-in-ten adults say a strong Russia is necessary to balance the influence of the West.

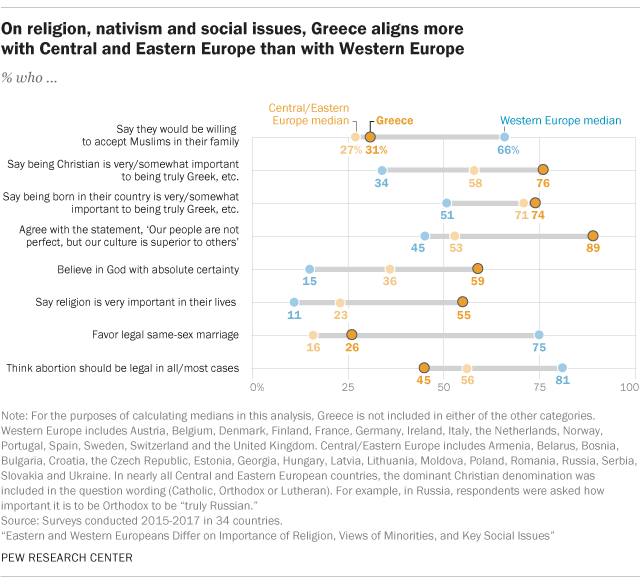

Greece is an overwhelmingly Orthodox Christian nation – much like Russia, Ukraine and other Eastern European countries. And, like many Eastern Europeans, Greeks embrace Christianity as a key part of their national identity. Three-quarters of Greeks say being Orthodox is at least somewhat important to being truly Greek; many other Central and Eastern Europeans link religion and nationality in this way (median of 57%), while fewer Western Europeans do (median of 34%). In addition, roughly a third of Greek adults say they would be willing to accept Muslims (31%) or Jews (35%) in their family, similar to the share who say this in other Central and Eastern European countries, but far below the shares who express acceptance of religious minorities in Western Europe.

Religion is also more important in Greeks’ personal lives than it is in those of many Western Europeans. Nine-in-ten Greeks (92%) believe in God – including 59% who say they believe with absolute certainty – while a median of just 15% of Western Europeans say they are certain of God’s existence. And 55% of Greek adults say religion is very important in their lives – more than double the share who say this in Ireland, Italy and Spain, and five times the share in France, Germany and the UK. Greece also is more religious than most Central and Eastern European countries by these measures.

Tied in part to higher levels of religious observance, Greeks are much more opposed to legal same-sex marriage and abortion than Western Europeans are. Seven-in-ten Greeks oppose or strongly oppose allowing gays and lesbians to marry legally – a perspective shared by virtually every Central and Eastern European country surveyed – while majorities in all 15 Western European countries surveyed favor same-sex marriage. And Greeks are divided on the question of whether abortion should be legal or illegal (45% vs. 52%), while majorities throughout Western Europe support legal abortion.

Much like Russians, Poles, and people in other Central and Eastern European countries, most Greeks say it is important to have been born in their country (74%) and to have family background there (85%) in order to be truly Greek, perhaps suggesting that immigrants cannot truly belong. Far fewer Western Europeans hold these views. In addition, a large majority of Greek adults say their culture is superior to others – similar to the shares of adults who say this is in Georgia and Armenia, but much higher than the shares in most countries across the continent.

To be sure, Greece does not align with its neighbors in Central and Eastern Europe on every issue. Ancient Greece is sometimes called the birthplace of democracy, and 77% of Greeks say democracy is preferable to any other kind of government – a view that does not have nearly as much traction in Russia, Ukraine and elsewhere in Central and Eastern Europe. Likewise, Orthodox Christianity first arose in the Greek world, and most Greek Orthodox Christians say they recognize the patriarch of the once-Byzantine Greek city of Constantinople as the highest authority of the Orthodox Church. By contrast, many other Orthodox Christians throughout Eastern Europe say the patriarch of Moscow (or their own national patriarch) holds this role.