Now that actual voting has started in the 2016 presidential campaign, there’s been more than the usual amount of chatter and speculation about whether this might be the year for a contested convention – particularly on the Republican side, given the large field of GOP candidates and the unpredictable nature of the contest so far.

A contested convention, for those who’ve never experienced one (which is to say, everyone under the age of 35 or 40), occurs when no candidate has amassed the majority of delegate votes needed to win his or her party’s nomination in advance of the convention. A candidate still might gather the delegates needed by the time balloting begins, in which case the nomination is settled on the first ballot. But should the first ballot not produce a nominee, most delegates become free to vote for whomever they wish, leading potentially to multiple ballots, horse-trading, smoke-filled rooms, favorite sons, dark horses and other colorful elements that have enlivened American political journalism, literature and theater.

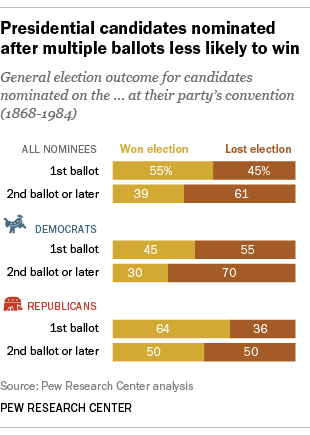

Even before primaries and caucuses came to dominate presidential campaigns in the 1970s, parties generally didn’t welcome contested conventions, especially when they went past the first ballot. And for good reason: Candidates who needed multiple ballots to be nominated seldom went on to win the White House.

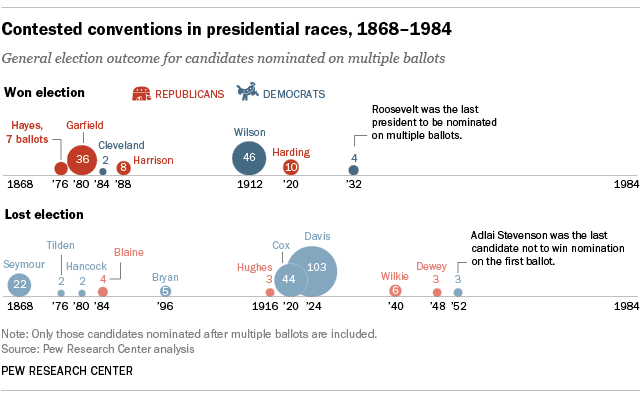

We looked at all 60 Democratic and Republican nominating conventions from 1868 (the first post-Civil War election) to 1984, the last time a convention presented even a glimmer of uncertainty. Over that time, 18 candidates (eight Republicans and 10 Democrats) were nominated on multiple ballots; of those, only seven were elected president (and four of them were running against another multiple-ballot nominee, so one of them had to win).

All told, of the 22 presidential elections held between 1868 and 1952 – the last multiple-ballot nomination to date, of Adlai Stevenson as the Democratic standard-bearer – 14 featured at least one major-party nominee who’d won on multiple ballots. (These often were referred to as “brokered conventions,” a term we’re avoiding here because of its connotations of shady backroom deals.)

As political scientist V.O. Key wrote decades ago, when contested conventions were still common, “the task of the convention is to unite the party in support of a presidential candidate” – still its main purpose in 2016. But sometimes, as Key noted, “animosities [between factions] reach such intensity that deadlock ensues and whatever party unity is achieved by the convention is mere façade.”

Conventions typically went to multiple ballots only in those kinds of situations – when there were two (or occasionally three) leading candidates, each representing a different geographical or ideological faction of the party, who were closely matched in strength. On the Democratic side, settling on a nominee was long complicated by a rule requiring two-thirds of the delegate votes, rather than a simple majority, to win the nomination. (The controversial two-thirds rule was finally abolished in 1936; afterward, only one Democratic convention, in 1952, went to multiple ballots.)

Multiple-ballot nomination battles generally ended in one of two ways. In most cases (12 of the 18 we examined), one of the leading candidates gradually accumulated sufficient support to overcome his rivals (as Republican Thomas Dewey did in 1948, for instance). But occasionally, a “dark horse” compromise candidate – who may have had just a handful of delegates at the start – eventually was nominated as a way to break a deadlock. Famous dark horses included Warren Harding, nominated on the 10th ballot by the 1920 Republican convention, and John W. Davis, declared the Democratic nominee in 1924 after a record 103 ballots.

As mentioned above, not all contested nominations were decided on multiple ballots. During the period we studied, 11 Republicans and 14 Democrats came to the convention facing some organized opposition (of varying degrees of seriousness), but managed to wrap up their nominations on the first ballot. In 1980, for instance, President Jimmy Carter had enough committed delegate votes for renomination, but Sen. Edward Kennedy, his main rival, sought a rule change to allow delegates to vote as they pleased on the first ballot – his only realistic chance of upsetting Carter. When Kennedy lost that rules fight, he withdrew from the race (though he still received more than 1,100 delegate votes).

The last time there was serious doubt about who a convention would nominate was in 1976, when Gerald Ford and Ronald Reagan battled for the Republican nomination in Kansas City. And the last time a leading candidate came to his or her convention with less than a majority of delegates was 1984, when Walter Mondale was a few dozen short. Despite a last-ditch effort by Gary Hart’s campaign to persuade black Mondale delegates to deprive Mondale of a first-ballot victory by voting for Jesse Jackson, Mondale cruised to the nomination.