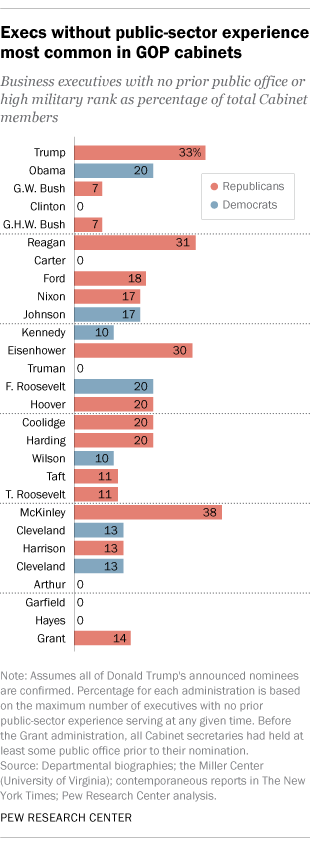

Should all of President-elect Donald Trump’s Cabinet nominees eventually be confirmed, he will start his administration with one of the most heavily business-oriented Cabinets in U.S. history.

Five of the 15 people Trump has nominated to be Cabinet secretaries have spent all or nearly all their careers in the business world, with no significant public office or senior military service on their résumés. That would be more businesspeople with no public-sector experience than have ever served in the Cabinet at any one time, according to a review and analysis by the Pew Research Center.

Before Trump, Ronald Reagan set the mark for bringing the most career businesspeople into the Cabinet. Four of Reagan’s initial 13 department heads in his first term were corporate executives.

Even accounting for the growth of the Cabinet over time, Trump would be in the top tier in terms of the percentage of career businesspeople as Cabinet secretaries. A third of the department heads in the Trump administration (33%) will be people whose prior experience has been entirely in the public sector. Only three other presidents are in the same range: William McKinley (three out eight Cabinet positions, or 37.5%), Ronald Reagan (four out of 13 positions, or 31%), and Dwight Eisenhower (three out of 10 positions, or 30%).

The five businesspeople Trump has nominated to date are Rex Tillerson, who resigned as Exxon Mobil’s chairman and CEO after being named secretary of state; hedge fund investor and Hollywood financier Steven Mnuchin, nominated as treasury secretary; Andrew Puzder, CEO of CKE Restaurants (which owns the Hardee’s and Carl’s Jr. chains), nominated as labor secretary; Wilbur Ross, a Wall Street veteran who invests in distressed companies, the nominee for commerce secretary; and Betsy DeVos, a billionaire philanthropist and school-voucher activist who is Trump’s pick for education secretary.

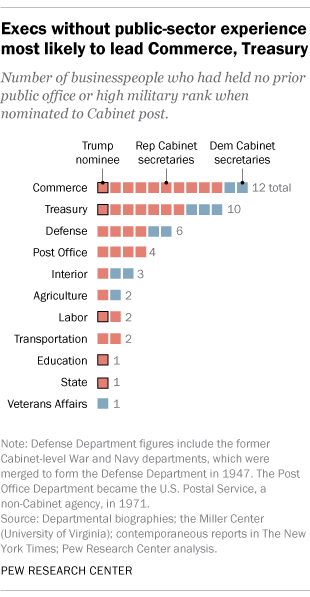

To conduct this analysis, we examined the backgrounds of all 589 people to have served as Cabinet secretaries since George Washington’s time, as well as all of Trump’s nominees. We didn’t include people who acted as interim secretaries, nor did we include other positions, such as CIA director or United Nations ambassador, that haven’t always been considered of Cabinet rank. We did, however, include the secretaries of departments that no longer exist: War and Navy (both now subsumed in the Defense Department); Commerce and Labor (split into separate departments in 1913); Health, Education and Welfare (divided by a 1979 law into Education and Health and Human Services); and the Post Office Department, which became the U.S. Postal Service in 1971.

We included as “public office” any elective office at the national, state or local level and any high military rank (general or admiral), as well as any significant appointive offices or staff positions. We excluded membership on advisory boards or commissions and part-time directorships, as well as service in partisan positions (such as national or state party chair). Academics and lawyers in private practice were not considered “businesspeople” for the purposes of our analysis.

Still, given the complexities of many people’s career paths, this analysis required a number of judgment calls. DeVos, for example, probably is best known as an advocate of vouchers and charter schools and as a large donor to Republican candidates (including many of the senators who will vote on her nomination). She also is a former chair of the Michigan Republican Party. But because DeVos also is chairman of The Windquest Group, her family’s private investment vehicle, we counted her as a businessperson.

Not counting Trump’s nominees, only 39 of the 589 current and former Cabinet secretaries (7%) were businesspeople who came to their positions with no public-sector experience. More commonly, people have either come to public service after long business careers or have gone back and forth between the public and private sectors. For that reason, several prominent names from the world of business and finance aren’t counted in our analysis.

For instance, Henry Paulson, the former chairman and CEO of Goldman Sachs who served as treasury secretary under George W. Bush, was early in his career a staff assistant to John Ehrlichman, Richard Nixon’s chief domestic policy adviser, and before that a Defense Department staffer. Caspar Weinberger was a top executive at Bechtel Corp. when Reagan appointed him defense secretary, but he had earlier served as health, education and welfare secretary under Nixon. And while Robert Rubin had a long career at Goldman Sachs before joining the Clinton administration, he served as the first director of the National Economic Council before being named treasury secretary.