Technological innovation has been changing the jobs people do, and the way they do them, at least since the first spinning jennies went into service in England’s textile industry in the 1760s. And for about as long, people have sought to forecast what new technologies might mean for the world of work — predictions that tend to be either utopian (2-hour workdays!) or dystopian (massive unemployment).

A new Pew Research Center report joins that tradition, gathering the opinions of nearly 1,900 experts on how advances in robotics and artificial intelligence will affect employment in the future. And again, opinions were divided, with about half saying robots and digital agents would leave significant numbers of workers — white and blue collar — idle by 2025, and the other half saying those technologies would lead to more new jobs than they displace. (Nor is this issue confined to the U.S.: The Belgian think tank Bruegel recently estimated how many current jobs in the 28 EU countries were vulnerable to computerization; the rates ranged from 47% in Sweden and the U.K. to 62% in Romania.)

Much as we try, no one can see into the future. But we can look to the recent past to get a sense for how technological change already has reshaped the U.S. workforce — creating new job categories while others fade away.

These changes can be tracked using data from the Occupational Employment Statistics program, a federal-state project that regularly surveys business establishments to generate employment and wage estimates for some 800 different occupations. The OES program periodically revises its occupational classification scheme — adding some occupations, dropping some and changing the definitions of others. While that can make year-over-year comparisons tricky, the changes themselves can illustrate emerging and declining job categories.

We compared the 2013 occupations list with the one for 1999, the earliest with a similar structure. While most of the 800 or so jobs were unchanged, there were some notable differences showing how new technologies already are affecting employment:

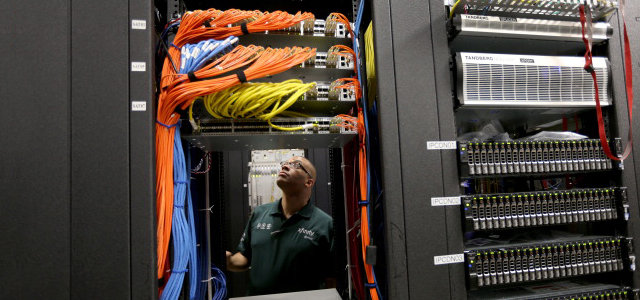

- In 2013, an estimated 165,100 Americans worked as computer network support specialists, 141,270 as computer network architects, and 78,020 as information security analysts. None of those occupations existed on their own in 1999, though some workers in those fields likely were included in broader job classifications such as “computer programmers” or “network systems and data communications analysts.” But listing them separately speaks to the importance of networked computing in today’s economy.

- Last year there were an estimated 112,820 web developers, another job classification that didn’t exist in 1999 (despite the dot-com mania that was cresting that year). Indeed, “web developer” wasn’t reported as part of the OES classification system until 2012 — an indication that the data often lag the evolution of the actual economy.

- Another new job: “logistician,” or someone responsible for analyzing and coordinating a business’ logistics. Powerful distributed computing and communications technologies have made far-flung supply chains, global distribution networks and “just-in-time” manufacturing (in which products are made to match orders as they come in, rather than being made in advance and held in inventory) not just possible but common. Now, an estimated 120,340 Americans are counted as working in this field, more than twice as many as when it was added in 2004.

- The rise of mobile communications is reflected in the category of workers who install, test and repair the equipment that makes the networks work. In 1999, when only about half of American adults owned a cellphone (and smartphones had just barely hit the market), those workers were called “radio mechanics,” because they mostly worked on radio-transmission equipment. In 2010 they were renamed “radio, cellular, and tower equipment installers and repairers,” and last year there were an estimated 14,090 of them — more than triple the number of “radio mechanics” in 1999.

- Telecommunications isn’t the only field where new technologies are creating new jobs. The 2013 OES survey reflects the growing importance of renewable energy in its estimates of 4,130 solar photovoltaic installers and 3,290 wind turbine service technicians. Neither job classification existed in 1999.

Next: Which jobs are most vulnerable to technological replacement?