Sept. 15 is the United Nations’ International Day of Democracy, an annual moment to assess the health of democracy around the world. Unfortunately, as numerous studies have demonstrated, democracy has been in decline in many nations in recent years.

Americans are unhappier and more divided than most about the state of their democracy, and particularly gloomy about its prospects for improvement.

The United States is no exception. In fact, Americans are unhappier and more divided than most about the state of their democracy, and particularly gloomy about its prospects for improvement. Americans certainly haven’t given up on democracy, but if the U.S. is going to turn around these negative trends, we may need a renewed democratic imagination and a new, broad-based conception of American identity to see past what feel like insurmountable obstacles.

The country’s notably grim political mood and desire for change show up across many survey questions. Cross-national surveys at Pew Research Center show Americans are among the most dissatisfied with the functioning of their democracy, and they are particularly negative on whether politicians care what voters think.

In a 2021 Center survey of adults in 17 advanced economies, 85% in the U.S. said their political system needs major changes or needs to be completely reformed. Italy and Spain were the only countries we surveyed where larger shares of the public expressed this view. Despite the desire for change, most Americans who said the U.S. political system needs to be fixed also said they are not confident it could be changed effectively.

Why have Americans lost confidence in our ability to reform? Surely, part of the answer is that our Constitution is very hard to amend. And at times, reverence for the Constitution can make it seem like an immutable set of rules, rather than a dynamic document designed to be updated as the country – and its ideas about democracy – evolve.

We’ve had the same Constitution for well over two centuries, and we’ve nonetheless had periods of significant reform. What makes today different?

But we’ve had the same Constitution for well over two centuries, and we’ve nonetheless had periods of significant reform. What makes today different? In part, the country’s deep political divisions. On issue after issue, Americans are sharply divided along partisan and ideological lines. Here again, international comparisons are instructive: Our polling finds that the gap between the ideological right and left is wider in the U.S. than in other countries on many issues, including abortion, climate change and same-sex marriage.

We’re also particularly conscious of our internal divisions. In a 2022 survey, 88% of Americans said there are strong conflicts in the country between people who support different political parties. South Korea was the only country we surveyed in which a larger share of adults held this opinion.

And the divisions extend beyond party and ideology. We’ve found that Americans are more likely than others to say there are strong conflicts between people of different ethnic or racial backgrounds in their country.

These perceived divisions make Americans feel more disconnected. While a 66% majority of Americans in 2023 said they feel close to other people in the country, this was the lowest percentage among the 24 nations polled. And Americans were the second lowest on a similar question about feeling close to people in their community. A disconnected nation lacks the bonds of trust necessary for bridging political and social divides.

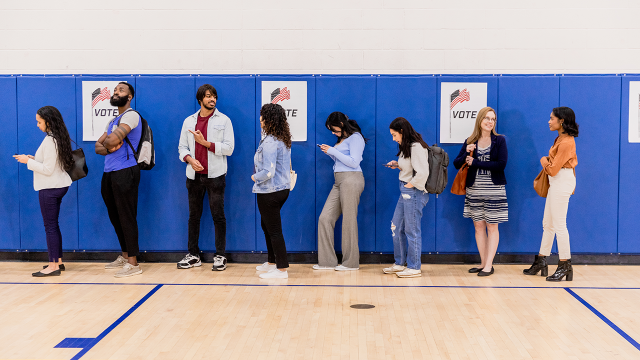

Today, as we enter the final weeks of a tumultuous election year, our political divisions are heightened, and Americans remain sharply divided into partisan camps.

Still, despite our deep political and social divisions, and the frustrations so many Americans feel, there are hopeful signs.

Americans are tired of division and existential, zero-sum political battles – especially since both sides feel like they are losing those battles.

For starters, Americans are tired of division and existential, zero-sum political battles – especially since both sides feel like they are losing those battles. And nearly two-thirds of U.S. adults (65%) say they always or often feel exhausted when thinking about politics.

Fortunately, they have ideas about how to change things. Last year, we asked respondents in the U.S. and 23 other nations to describe in their own words how their country’s democracy could improve. Americans had a lot to say. They want government reform and different political leaders. They want to reduce the influence of special interests and money in politics. And there is broad support for specific reforms, such as term limits for Congress, age limits for federal elected officials and Supreme Court justices, and abolishing the Electoral College.

The challenge for would-be reformers is overcoming Americans’ pessimism about our capacity for change. Americans will need to recapture their sense of political imagination and regain confidence in their ability to transcend political divisions and trust one another long enough to pursue difficult changes that will make democracy work better.

This may require developing new, more unifying and more inclusive forms of American identity – essentially, a conception of America that is broad enough for everyone to have a place in it, and for people to feel that losing an election won’t mean losing their democracy and their idea of what America means.