This year, as in every even-numbered year, about a third of U.S. Senate seats are up for election. Given the 51-49 split in the Senate between Democrats and Republicans (including the four independents who caucus with Democrats), each of those races has the potential to tip the chamber’s balance of power. But elections aren’t the only way that can happen.

We compiled information on state procedures for filling U.S. Senate vacancies from each state’s online code of state law. Data on senators’ ages, party affiliation and length of service comes from the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

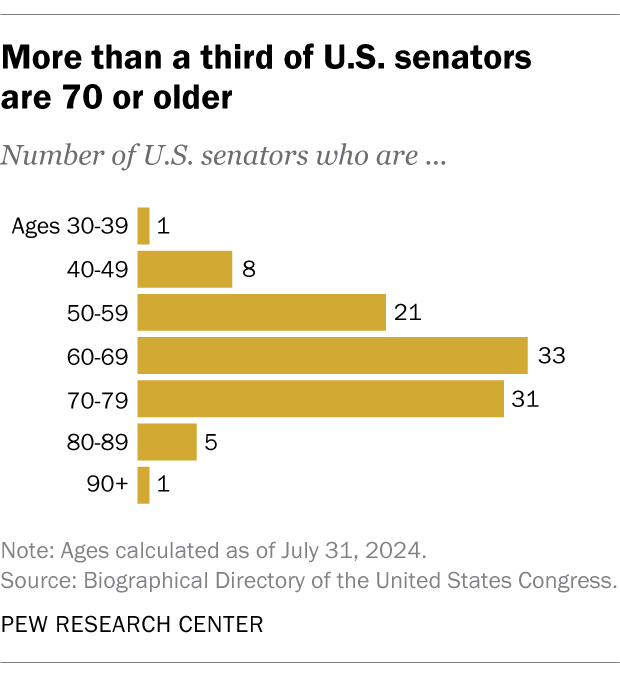

All ages are calculated as of July 31, 2024. In the comparison of senators’ and governors’ party affiliations, the four independent senators are counted as Democrats, since they all caucus with the Senate Democrats.

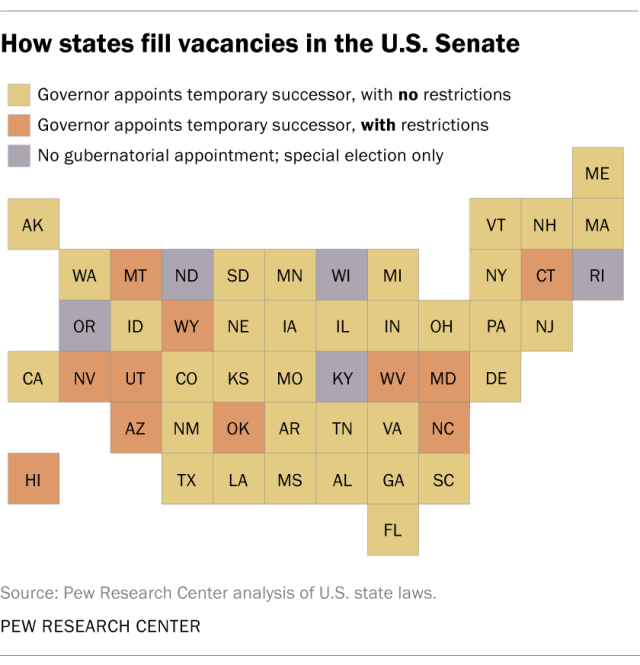

Should a sitting senator resign, die or otherwise leave office during their term, governors in 45 states have the power to appoint a temporary replacement. In most of those states, governors have free rein to appoint whomever they wish, with the appointee serving until a successor is elected to fill out the rest of the term.

This has already happened twice during the current Congress. In January 2023, Republican Sen. Ben Sasse of Nebraska resigned to become president of the University of Florida. Nebraska’s GOP governor, Jim Pillen, appointed the state’s former governor, Pete Ricketts, to replace Sasse. (Ricketts is running in a special election this year to complete the rest of Sasse’s term, which ends in January 2027.)

And in September 2023, longtime Sen. Dianne Feinstein, a California Democrat, died at age 90. Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom appointed Laphonza Butler to fill the vacancy. (Butler is not running for the remainder of Feinstein’s term or for the new term that begins in January 2025.)

A third senatorial appointment likely will come soon. Sen. Bob Menendez of New Jersey, who has been convicted of multiple federal corruption charges, has said he will resign his seat effective Aug. 20. Gov. Phil Murphy, a fellow Democrat, is expected to quickly appoint a successor to Menendez.

There may be another appointment, too. Should the Republican presidential ticket of Donald Trump and JD Vance win in November, GOP Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine would appoint someone to fill Vance’s Senate seat.

The possibility of appointed senators tipping the partisan balance – or at least giving an electoral advantage to one party or the other – is brought into sharper relief when one considers that this is the oldest Senate of any in U.S. history. The mean age of current U.S. senators, as of July 31, is 65.2. Almost a third of senators (31) are in their 70s, five are in their 80s, and one (Iowa Republican Chuck Grassley) will turn 91 in September.

One senator in the 80-plus club, Maryland Democrat Ben Cardin (age 80), is retiring at the end of his term this year. Two octogenarian independents – Bernie Sanders of Vermont (82) and Angus King of Maine (80) – are running for reelection. Iowa’s Grassley won his eighth term in 2022. The terms of the other two oldest senators – Kentucky’s Mitch McConnell (82) and Idaho’s Jim Risch (81) – don’t expire until 2027.

Senate replacement procedures vary by state

The current system for filling vacant Senate seats dates to the ratification of the 17th Amendment in 1913. Along with letting people elect their senators directly – state legislatures had chosen them up to that point – the amendment gave states the option of letting their governors appoint temporary replacements.

The only states not to do so are Kentucky, North Dakota, Oregon, Rhode Island and Wisconsin. In those states, vacancies can only be filled by special election. Kentucky is the latest to join this group, after its majority-Republican legislature took the appointment power away from Democratic Gov. Andy Beshear earlier this year.

Among the 45 states that do give their governors authority to name replacement senators, 11 limit their field of choice in some way. Six states – Hawaii, Maryland, Montana, North Carolina, West Virginia and Wyoming – make the governor choose from a list of three nominees submitted by the previous senator’s party. Utah requires the same kind of list, but from the state legislature. Arizona, Nevada and Oklahoma simply require the governor to choose someone from the previous senator’s party.

Connecticut has the most restrictive rules: The governor can fill a Senate vacancy only if there’s a year or less remaining in the term, and their choice must be approved by a two-thirds vote in each house of the state legislature.

One reason for such limitations is to prevent a governor from appointing someone of their own party to a Senate seat formerly held by the other party. In 2013, for instance, New Jersey’s then-Gov. Chris Christie, a Republican, appointed state Attorney General and fellow Republican Jeffrey Chiesa to the seat that had been held by the late Frank Lautenberg, a Democrat. Chiesa served for just under five months, until Democrat Cory Booker won the special election for the rest of Lautenberg’s term.

Currently, 13 of 50 governors belong to a different party than at least one of their state’s senators. But only seven of those 13 would be able to do what Christie did in New Jersey. The others either can’t appoint temporary senators at all or are required to choose someone of the same party as the former senator.

The 17th Amendment also gives states considerable leeway in deciding how long temporary senators can serve until a special election. In 31 states, special Senate elections are held concurrently with regular general elections. In some cases, those special elections coincide with the next scheduled general election, but in other cases – especially if the vacancy occurs late in the election cycle – they coincide with the general election after the next one.

Six states have specific timetables for holding special Senate elections, usually a certain number of days following the start of the vacancy. Nine states either set a separate date for the special election or hold it concurrently with the next general election, depending on when the vacancy occurs. And four states have few or no rules on when a special election must be held, effectively leaving the decision up to the governor.

Note: This is an update of a post first published May 3, 2022.