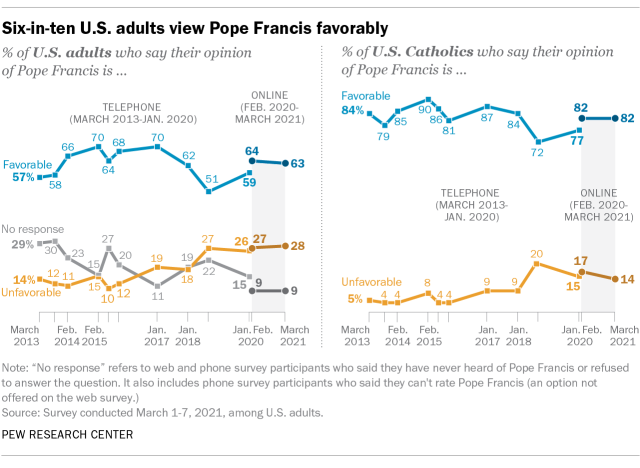

Pope Francis’ popularity dropped in the United States a few years ago amid a sex abuse crisis in the U.S. Catholic Church. But Americans’ opinions of the pontiff have since rebounded, and between February 2020 and March 2021 – 13 months that included moves by Francis to expand the role of women in the church as well as a widening debate about whether President Joe Biden should be denied Communion – views toward Francis remained fairly stable.

About six-in-ten U.S adults (63%) have a “very” or “mostly” favorable opinion of Pope Francis, according to a Pew Research Center survey conducted in March using the Center’s online American Trends Panel. This is nearly identical to the share of adults who had a favorable view of Francis in February 2020 (64%).

The pope’s favorability also has remained steady among U.S. Catholics, with 82% of Catholics in both the March 2021 and February 2020 surveys saying they have a favorable opinion of the pope.

These March 2021 and February 2020 results are not entirely comparable to figures from earlier surveys the Center conducted by telephone. Online and phone surveys sometimes produce disparate results, a polling phenomenon called a mode effect. One key difference is that online polls tend to result in fewer respondents declining to answer the question if there are fewer opportunities to express “no opinion.” This analysis indicates that any change in the results between January 2020 (when this question was last asked on the phone) and March 2021 was likely due to fewer people declining to give an opinion on the web survey.

Pew Research Center conducted this analysis to track opinions of Pope Francis and to study the effects of survey mode on attitudes about the pontiff. We most recently surveyed 12,055 U.S. adults (including 2,492 Catholics) from March 1 to 7, 2021. All respondents to the survey are part of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education, religious affiliation and other categories. For more, see the ATP’s methodology.

The study also uses data from two additional surveys – one administered online and the other on the telephone – conducted at roughly the same time in 2020. In January 2020, we surveyed 1,504 U.S. adults by phone, including 270 Catholics, and in February we conducted an online survey of 6,395 U.S. adults, including 1,188 Catholics. All who took part in the online survey were members of the ATP at the time they were surveyed. Respondents to the phone survey were randomly selected using a combination of landline and cellphone random-digit-dial samples, and interviews were conducted in both English and Spanish.

Here are the questions used for this analysis, along with responses.

Here are methodologies for the March 2021 web survey, the February 2020 web survey and the January 2020 phone survey.

People sometimes – though not always – respond differently to similar questions on the same topics in online and telephone polls. These so-called mode effects may occur for a variety of reasons. For example, survey respondents might be reluctant to share embarrassing or socially undesirable information with a live phone interviewer (as opposed to online polls, which are self-administered) or because people process information that they read themselves differently from information that is read to them aloud.

With surveys increasingly being conducted online, Pew Research Center has been measuring how the shift in mode affects the answers to certain questions, such as views on the death penalty. To assess how responses about Pope Francis might differ by mode, the Center last year conducted two separate surveys at roughly the same time – one via telephone in January 2020 and one via the web in February 2020.

In the January 2020 phone survey, 59% of U.S. adults said they had a “very” or “mostly” favorable opinion of Pope Francis, compared with 64% who said this in the online poll a month later. Among Catholics, 77% expressed a favorable view by phone in January and 82% did so online in February. (This 5 percentage point gap among Catholics is not statistically significant.)

Minor differences in question wording between the phone and online surveys produced slightly different opinions about the pope, though the general pattern of responses in the two surveys is similar. Phone respondents have the opportunity to volunteer that they have no opinion of Pope Francis, either by saying they “can’t rate” him, they “haven’t heard of” him, or by simply refusing to answer the question. In the January 2020 phone survey, 15% of U.S. adults gave one of these three response options.

When this question is asked on the web, respondents had two opportunities to decline to offer an opinion: They were given an explicit option to say they had “never heard of this person,” or they could refuse to answer the question – but they were not offered the choice of “can’t rate” Francis. Overall, 9% of all respondents in the February 2020 online survey said they had never heard of the current pope or declined to answer the question.

This 6-point difference – from 15% by phone to 9% online – is a result of both Catholics and non-Catholics being more likely to share their opinion about Pope Francis when taking the survey online. Both groups were 6 points more likely to give Francis a rating in the February web poll. Among Catholics the shift was from an 8% nonresponse rate to 2%; for non-Catholics it was from 17% to 11%.

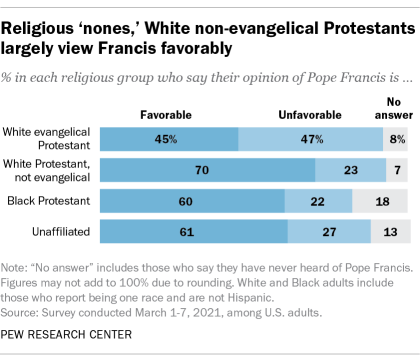

But members of some non-Catholic faiths were especially likely to share their opinion of Francis online even though they typically declined to on the phone. For example, White evangelical Protestants were 11 points more likely to rate the pontiff when asked online. Among White Protestants who do not identify as evangelical, the difference was 14 percentage points.

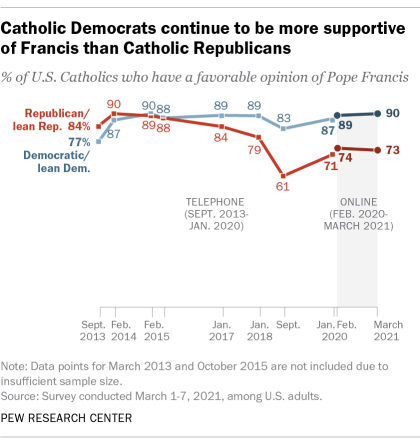

Views of Pope Francis have remained fairly stable among Catholic subgroups, too. For example, Catholics who identify as Democrats or who lean toward that party continue to have a more positive opinion of Francis than their Republican counterparts, a partisan pattern that has held since 2018. In the latest survey, 90% of Catholic Democrats expressed a favorable opinion of the pope, compared with 73% of Catholic Republicans and GOP leaners.

Moreover, the latest survey finds little difference in opinions of Francis among Catholics who attend Mass regularly and those who go less often – consistent with patterns seen in previous years. Among weekly Mass-goers, 84% said in March that they have a very or mostly favorable opinion of the pope, as did 82% of Catholics who attend Mass less often, including those who say they never go.

Among non-Catholics, views about Pope Francis also have not changed much. In the March survey, majorities of White Protestants who do not identify as evangelical (70%), religiously unaffiliated adults (61%) and Black Protestants (60%) say they have a favorable opinion of him. White evangelical Protestants are more divided in their opinion of the pontiff, with similar shares expressing favorable (45%) and unfavorable (47%) views. Due to sample size limitations, this analysis does not separately report on some smaller religious groups, including Jewish and Muslim Americans.

Note: Here are the questions used for the March 2021 survey, along with responses, and its methodology.