Today is Election Day 2013, but many eyes are already looking ahead to 2014. In the wake of the federal government shutdown and the narrow avoidance of a default, chatter has grown that Democrats might be able to take advantage of the GOP’s unpopularity and general anti-incumbent sentiment to regain control of the House — or at least cut into the Republicans’ 231-to-200 majority. (Four seats are vacant).

A swing of 18 House seats would be enough to give the Democrats control, which might not seem like much. But in House elections from 1992 to 2012, the median net party gain was just eight seats, according to Brookings’ Vital Statistics on Congress. And in midterm elections, the party holding the presidency usually loses seats: In only two of the 17 midterm elections since the end of World War II, in fact, did the president’s party gain seats (1998 and 2002).

In addition, only a few dozen seats are currently considered competitive. Independent analyst Stuart Rothenberg, for instance, puts the number at 51, almost equally divided between Democrats and Republicans, with the rest deemed safe, at least for now.

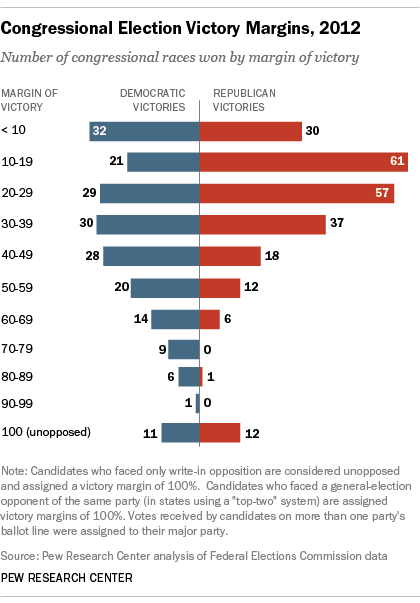

An examination of the 2012 election results shows just how few House races were at all close. Out of 435 seats total, in only 62 (14.3%) were the winner and runner-up separated by fewer than 10 percentage points. Democrats won 32 of those “close-ish” contests, Republicans 30.

In 143 of the 234 seats won by Republicans last year, the winner beat the runner-up by 20 percentage points or more; 148 of the 201 Democratic victories were by 20 points or more. Twenty Republicans and 11 Democrats either ran completely unopposed or had no major-party opponent. In nine districts (eight of them in California), the general election was between two candidates of the same party. (California, along with Louisiana and Washington, uses a “top-two” system rather than traditional party primaries. All candidates of all parties run in the first round; the top two finishers, regardless of party, proceed to the second round.)

Political scientists and analysts disagree on why so few House districts are competitive; some blame gerrymandering, while others say the district maps reflect a politically polarized America where people are more likely to live among those who think like they do. Regardless, House Speaker John Boehner (who won a 12th term unopposed last year) probably has more to fear from his own caucus than the voters in his district, while Democrats hoping to put Nancy Pelosi (re-elected with 70.2% of the vote) back in the speaker’s chair will have a high hill to climb.