Many people throughout the countries surveyed – including all major religious groups – express a general acceptance of religious diversity. For example, large majorities in each country say they would accept followers of other religions as their neighbors. Most people across the region also describe other religions as peaceful and as compatible with their national culture and values.

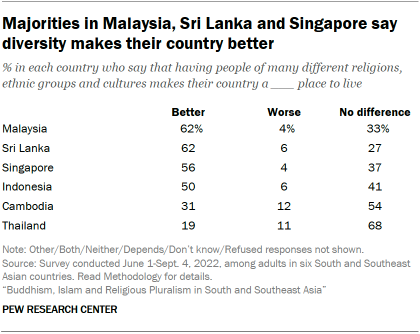

Moreover, survey respondents across the region are far more likely to say that religious, ethnic and cultural diversity has a positive impact on their country than to say it has a negative impact. In Malaysia (62%), Sri Lanka (62%) and Singapore (56%), majorities say that having people from many different backgrounds makes their country a better place to live, while just 6% or fewer of adults in these countries say diversity makes their country worse. (Many people across the region also say that religious, ethnic and cultural diversity has neither a positive nor a negative impact on their country; 68% of Thai adults and 54% of Cambodians take this ambivalent position.)

Along with broad support for religious coexistence, however, the countries surveyed also are home to strong nationalist sentiment. Clear majorities across these countries agree with the notion that their “culture is superior to others.” And most people in every country but Singapore say that having been born in their country, as well as belonging to its dominant ethnic and/or religious groups is very important to “truly” be a member of the nation (e.g., that being Buddhist is very important to be truly Cambodian, or that being Muslim is very important to be truly Indonesian).

In general, people who say religion is very important in their lives are especially likely to see birth, ethnicity and religion as key to national identity and to express a sense of cultural superiority. Adults with relatively low levels of education also are more likely to see birthplace and religion as critical to national identity and to completely agree that their country’s culture is superior, while people with higher levels of education are more likely to express opinions tolerant of other religions. For instance, in Thailand, 55% of adults with at least a secondary education view Islam as very or somewhat peaceful, compared with 39% of those with less education.

This chapter also looks at views about whether violence is justified over political or religious beliefs, as well as threats Muslims and Buddhists see toward their religions.

Attitudes toward diversity of religion, ethnicity and culture

Across the region, the most common view is that having people from many different religions, ethnic groups and cultures makes a country a better place to live. Large shares also express the view that this kind of diversity doesn’t make much of a difference. Far fewer take the stance that diversity makes their country worse.

For example, a majority of Malaysian adults (62%) say that having a diverse population improves their country, while 33% say the diversity makes no difference and just 4% say religious, ethnic and cultural diversity makes their country a worse place to live.

In Cambodia and Thailand, however, the most common response is that diversity doesn’t make much of a difference; just 19% of Thai adults say diversity makes their country better, while 68% say it doesn’t make much difference and 11% say it makes Thailand worse.

Hindus, a religious minority across the countries surveyed, generally are more likely than other religious groups in the region to say that diversity makes their country a better place to live. Most Christians and Muslims share this view, while Buddhists are less likely to say that having people of different religious, ethnic and cultural groups makes their country a better place to live.

Views of other religions as peaceful

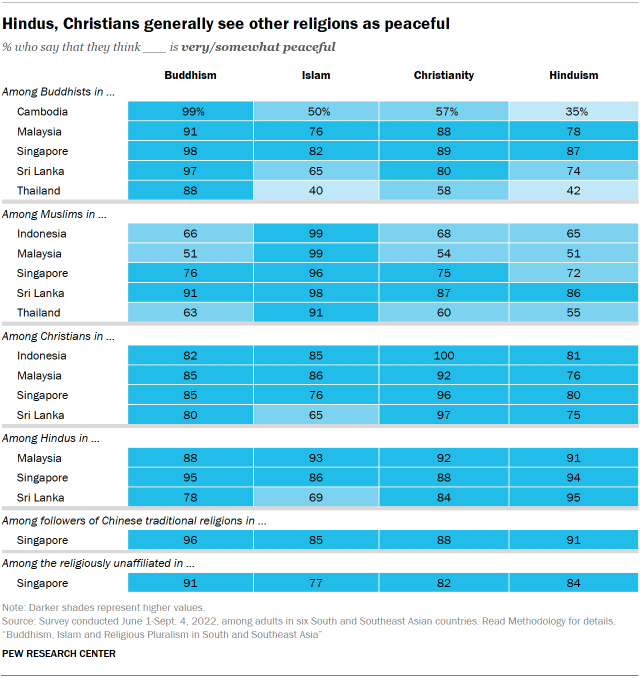

Most adults surveyed across the region say they view other religions as very or somewhat peaceful. Far fewer say that other religions are not very, or not at all, peaceful.

But there are some instances where a religion is not seen as peaceful by a substantial share of respondents in a given country. For example, 36% of Thai Buddhists say Islam is not peaceful, while a similar share of Thai Muslims (35%) say the same about Buddhism.

Among the region’s main religious groups, Hindus and Christians are the most likely to view other religions as peaceful, and Muslims are generally the least likely to describe other religions as peaceful. Still, clear majorities of Muslims in most countries do view other religions as peaceful. For example, 76% of Muslims in Singapore say Buddhism is a peaceful religion, while Singaporean Hindus (95%) and Christians (85%) are even more likely to take that position.

Sri Lankan Muslims are a notable outlier, representing one of the groups most likely in the entire region to describe other religions as peaceful. About nine-in-ten Sri Lankan Muslims (91%) say that Buddhism is very or somewhat peaceful, with similarly high shares saying the same about Christianity (87%) and Hinduism (86%).

Sizable shares of the population in Buddhist-majority Cambodia and Thailand report that they “don’t know” or otherwise refuse to answer when asked whether Islam, Christianity and Hinduism are peaceful religions. This may be due, in part, to unfamiliarity. For example, 45% of Cambodian respondents do not give an answer when asked about Hinduism, a religion with virtually no presence in the country.

Willingness to have neighbors from other religions

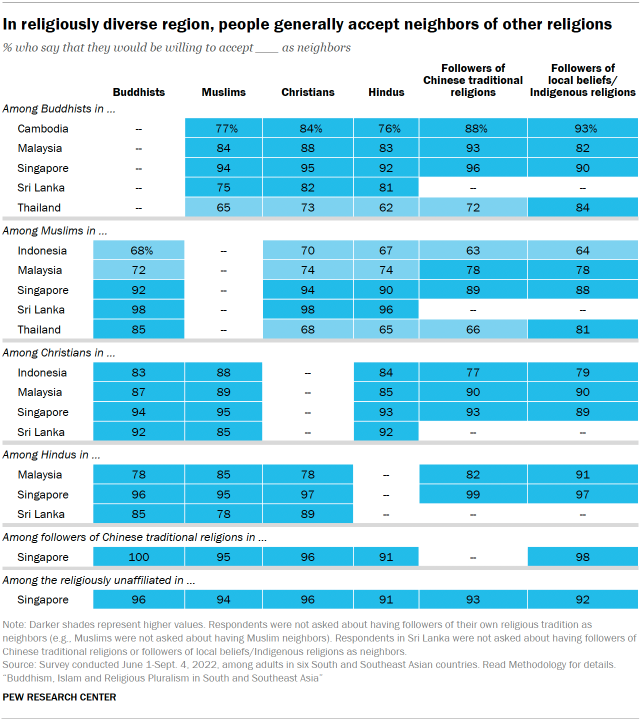

To further measure religious tolerance, the survey asked whether respondents would be willing to accept followers of different religions as neighbors. Consistent with the broader regional pattern, majorities – often overwhelming ones – of all major religious groups in the countries surveyed report a willingness to accept members of other religions as neighbors.

And even though followers of Chinese traditional religions and practitioners of local beliefs or Indigenous religions have a limited presence in these countries, clear majorities across the region say they would accept members of these groups as neighbors.

In many cases, younger adults (ages 18 to 34) are more willing than older people to accept members of other groups as neighbors. However, most older adults also express a willingness to live near people of other religions. For example, 78% of younger Thai adults say they would be willing to accept Hindus as neighbors, as do 57% of Thai adults ages 35 and older.

People with higher levels of education also are more likely to say that they would accept members of other religious groups as neighbors. For instance, 80% of Indonesians with at least a secondary education say they would accept practitioners of Chinese traditional religions as neighbors, compared with 55% of Indonesians with less education.

Men also are generally more likely than women to say they would accept members of other religious groups as neighbors.

How religions fit with national cultures

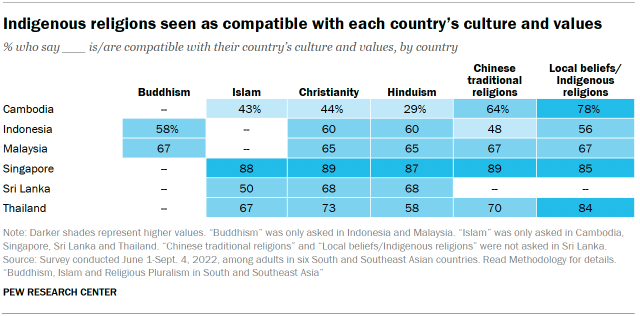

Further demonstrating the broad religious tolerance in the countries surveyed, majorities in most countries agree that other religions are compatible with their country’s way of life. For example, roughly two-thirds of Sri Lankans say that Christianity (68%) and Hinduism (68%) are compatible with Sri Lanka’s culture and values. (People were not asked about the predominant religion in their country, so Sri Lankans were not asked whether Buddhism is compatible with Sri Lankan culture.)

Adults in the religiously diverse country of Singapore are the most likely to view several religions as compatible with their country’s culture and values, with at least eight-in-ten saying this is the case for Islam, Christianity and Hinduism, as well as for Chinese traditional religions and local beliefs or Indigenous religions.

On the other hand, Cambodians are by far the least likely of those surveyed to say various religions are compatible with their country. Fewer than half of Cambodian adults say that Christianity (44%), Islam (43%) and Hinduism (29%) are compatible with Cambodian culture and values, although most say that local beliefs or Indigenous religions (78%) and Chinese traditional beliefs (64%) are compatible with their national culture. In fact, majorities in all countries surveyed say that local beliefs and Indigenous religions are compatible with their national culture and values.

Once again, Cambodia has higher rates of respondents who choose not to answer these questions about various religious communities, including nearly one-third who do not offer an opinion about whether Hinduism is compatible with the country’s culture and values.

Highly religious adults in most countries are less likely than others to perceive non-majority religions such as Christianity and Hinduism as compatible with their national values. For example, 64% of Malaysians for whom religion is very important view Christianity as compatible with Malaysian culture and values, compared with 73% of less religious Malaysians.

There also are differences by gender and community type, with men and urban respondents generally more likely than women and rural residents to view Hinduism and Christianity as compatible with the values and culture of their country.

These differences in opinion are still overshadowed by the broad tolerance displayed throughout the region. Though women, residents of rural areas, and more religious respondents are somewhat less likely to view minority religions as compatible with their national culture and values, most people within these three groups still generally say that minority religions are compatible.

Key elements of national identity

Overwhelming majorities across the countries surveyed say that values associated with order and intergroup harmony – such as being polite and welcoming, and respecting their nation’s institutions and laws – are very important to truly be a part of their nation (e.g., that it is very important to be polite and welcoming to be truly Cambodian).

Most people in the region also say willingness to support the country when others criticize it is very important to national identity. For instance, at least nine-in-ten adults in Indonesia say each of these three qualities is very important to being truly Indonesian.

Strong majorities in most surveyed countries also say being able to speak the national language, having been born in the country, being a part of the majority ethnic group and being a member of the main religious group are very important to truly share their nationality.

Singaporeans are far less likely than others in the region to emphasize these nativist elements to national belonging. Around four-in-ten (39%) say that it is very important to have been born in Singapore to truly be Singaporean, and only 19% say being ethnically Chinese is highly important to national identity. (About three-quarters of Singaporeans are ethnically Chinese.) Even fewer (13%) say it is very important to be Buddhist to be truly Singaporean, which may be unsurprising considering there is no majority religious group in the country.

Furthermore, only 27% of Singaporeans say it is very important to be able to speak Mandarin Chinese to truly share the national identity. Singaporeans also were asked about the importance of speaking “Singlish,” a Singaporean colloquial dialect of English, to national identity, to which 23% said it is very important to be able to speak Singlish to be truly Singaporean. The relatively low importance of language to national identity may be due to the multilinguistic nature of Singapore. Singapore has no majority language spoken at home, and the country recognizes four official languages: English, Mandarin Chinese, Malay and Tamil.

While Sinhala is the predominant language in Sri Lanka, a significant portion of the country speaks Tamil. A slim majority (56%) of Sri Lankans say that being able to speak Tamil is very important to being truly Sri Lankan, compared with 83% who say the same about Sinhala.

Within each of Sri Lanka’s main ethnic groups, the Sinhalese and Tamil people, most view the ability to speak their own language as very important to being truly Sri Lankan. However, less than two decades after the end of a long civil war fought mostly along ethnic lines, large majorities in both groups also view the other community’s language as at least somewhat important.

Among the majority Sinhalese, 96% say that being able to speak Sinhala is very or somewhat important to being truly Sri Lankan, while 85% say the same about Tamil. Among the minority Tamil, 90% say that it is at least somewhat important to speak Tamil to truly be part of the nation, while 84% say the same about Sinhala.

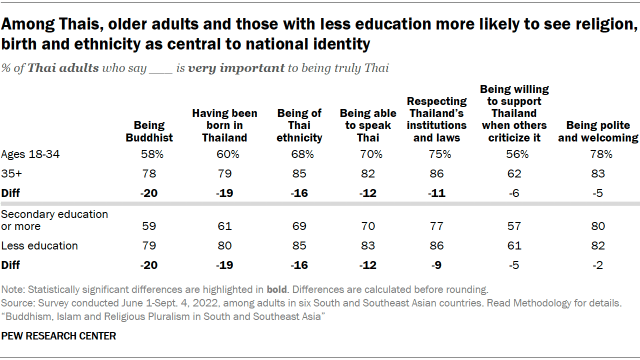

In general across the countries surveyed, age and education level are strongly linked with views toward the nativist elements of national identity. Though majorities among all age groups and education levels tend to find these elements very important to truly sharing their nationality, younger and highly educated adults are less likely than their older or less-educated counterparts to identify nativist requirements as very important to national identity.

In Thailand, for example, younger adults (ages 18 to 34) are less likely than their elders to say that it is very important to have been born in Thailand to truly be Thai (60% vs. 79%). The same difference exists between Thais with at least a secondary education and those with fewer years of formal schooling (61% vs. 80%).

There are similar gaps when it comes to the importance of religion to Thai identity, with 20 percentage points separating these age and education groups in the shares who say being Buddhist is very important to being truly Thai. But on two questions about the civic-oriented elements of national identity – the importance of supporting their country in the face of criticism, and the importance of being polite and welcoming – there is no significant difference between the responses of older and younger Thais or Thais of different education levels.

Followers of the majority religion in each country overwhelmingly say that membership in their religion is very important to truly being a part of their nation. For example, 79% of Malaysian Muslims say that it is very important to be Muslim to be truly Malaysian; far fewer Malaysian Christians (32%) place such importance on being Muslim to Malaysian identity.

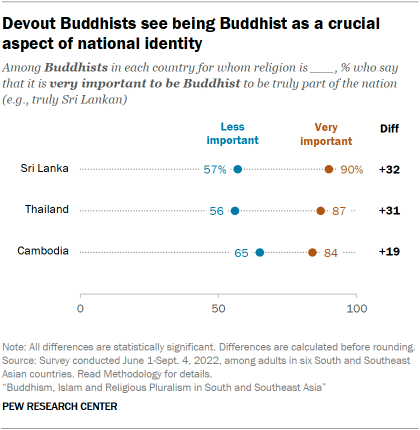

In the Buddhist-majority countries surveyed, Buddhists who consider religion very important in their own lives are also more likely to say that Buddhism is very important to national identity.

However, majorities of Buddhists for whom religion is personally not as important still express the view that Buddhism is very important to truly be a part of the nation. For instance, 90% of Sri Lankan Buddhists who consider religion very important in their lives say that Buddhism is very important to being truly Sri Lankan, compared with 57% of less devout Sri Lankan Buddhists who take this position.

This pattern among more- and less-religious Buddhists holds for other nativist measures as well. For example, 82% of more religious Thai Buddhists say being born in Thailand is very important to Thai identity, compared with 56% of Thai Buddhists who place less personal importance on religion.

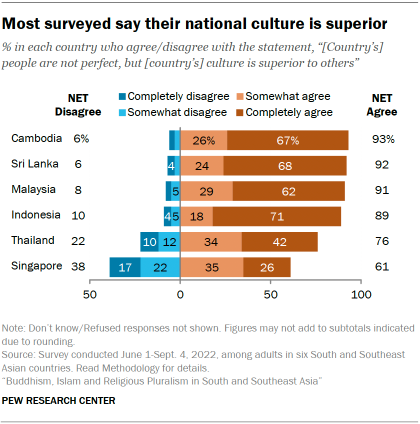

Feelings of cultural superiority

Beyond measuring what people view as important to their national identity, the survey sought to gauge nationalism by asking respondents whether they completely agree, somewhat agree, somewhat disagree or completely disagree with the notion that their country’s culture is superior to others. For example, people in Malaysia were asked whether they agree that “Malaysian people are not perfect, but Malaysian culture is superior to others.”

Clear majorities in each country either completely or somewhat agree that their culture is superior to others. But while roughly nine-in-ten or more agree with this statement in Cambodia (93%), Sri Lanka (92%), Malaysia (91%) and Indonesia (89%), fewer feel the same way in Thailand (76%) and Singapore (61%).

Though adults of different religions respond similarly to this question, those who say that religion is very important in their lives are more likely than others to completely agree that their culture is superior to others. For example, 70% of Sri Lankans for whom religion is very important completely agree that Sri Lankan culture is superior to others, compared with 41% of Sri Lankans for whom religion is less important.

Pew Research Center also has asked this question in India, as well as in many countries across Europe (including Central and Eastern Europe as well as Western Europe). A strong consensus appears across South and Southeast Asia: The 90% of Indian adults who say they either somewhat or completely agree that “Indian people are not perfect, but Indian culture is superior to others” broadly aligns with the new survey’s results across South and Southeast Asian countries. Western Europeans (45% median) and Central and Eastern Europeans (55% median) are far less likely to say their country’s culture is superior.

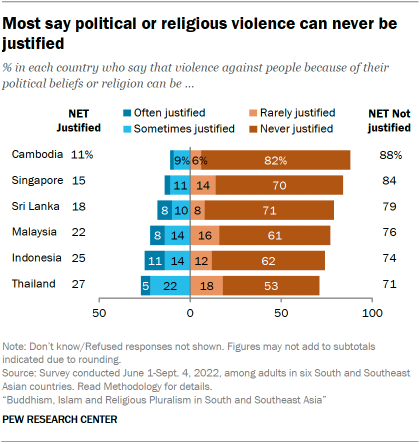

Views toward violence based on political or religious beliefs

In all six Southeast and South Asian countries surveyed, roughly half or more of the public says that using violence against people because of their political beliefs or religion can never be justified. At least seven-in-ten adults in Cambodia (82%), Sri Lanka (71%) and Singapore (70%) take this position.

Thai adults are less inclined to say such violence can never be justified, with around half of the survey respondents in Thailand (53%) taking this stance.

Roughly a quarter of adults in Thailand (27%), Indonesia (25%) and Malaysia (22%) say that violence can sometimes or often be justified against people because of their political beliefs or religion.

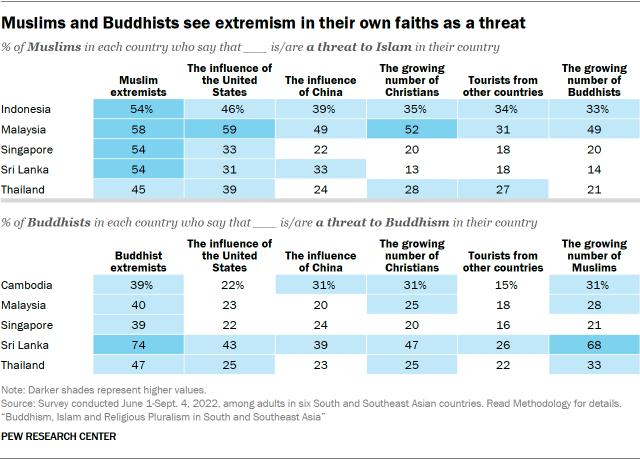

What Muslims and Buddhists see as threats to their religions

When asked about a series of potential threats to their religion in their country (e.g., Sri Lankan Buddhists were asked about threats to Buddhism in Sri Lanka), Muslims and Buddhists are most likely to see extremists from their own faith as a threat. Muslims generally are more likely than Buddhists to say extremists from their own religion are a threat, but in Sri Lanka, Buddhists are much more likely than Muslims to perceive such extremists as a threat (74% vs. 54%).

Muslims across the region are generally more likely than Buddhists to perceive the influence of the United States as a threat to their religion. For example, 39% of Thai Muslims say U.S. influence is a threat to Islam in their country, compared with 25% of Thai Buddhists who say the same about Buddhism. Sri Lanka is an exception to this pattern: Buddhists there are more likely than Muslims to see the U.S. as a threat to their faith. No such pattern exists when it comes to views about the influence of China.

Among both Muslims and Buddhists, most people do not see growing populations of other religious groups in their countries as threats to their religion. Buddhists were asked about “the growing number” of Muslims in their country, while Muslims were asked about the growing number of Buddhists, and members of both communities were asked about the growing number of Christians. (These questions were designed to gauge demographic anxieties, regardless of whether or not these minority populations are actually growing within the countries surveyed.)

However, in some instances, substantial shares do identify the increasing presence of other religions as a threat. Around half of Malaysian Muslims (52%) identify the growing number of Christians as a threat to Islam in Malaysia, and a clear majority of Sri Lankan Buddhists (68%) say that the growing number of Muslims is a threat to Buddhism in Sri Lanka.

Among both Muslims and Buddhists, highly educated adults are more likely than those with less education to say that extremists within their own religion are a threat. For instance, 58% of Indonesian Muslims with at least a secondary education say that Muslim extremists are a threat to Islam in their country, compared with 51% of Muslims in Indonesia with less education who say this.

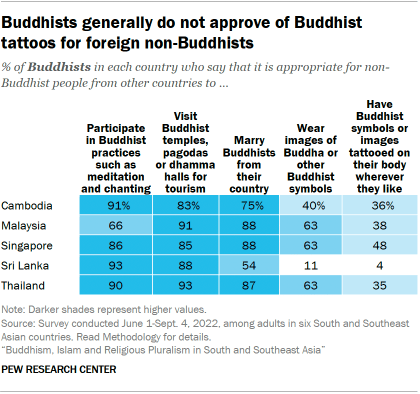

What do Buddhists see as appropriate for foreign non-Buddhists?

News reports have highlighted the tension in this region between local Buddhists and foreign tourists, with local authorities taking action against tourists for disrespecting local temples or displaying tattoos of Buddha.

Although most Buddhists in the countries surveyed do not see foreign tourists as a threat to Buddhism in their country, the survey also asked Buddhists if they see a variety of activities as appropriate for foreign non-Buddhists to participate in.

Vast majorities of Buddhists say it is appropriate for foreign non-Buddhists to participate in Buddhist practices such as meditation and chanting, and to visit Buddhist temples, pagodas or dhamma halls for tourism. For example, 93% of Thai Buddhists say it is appropriate for non-Buddhist tourists to visit Buddhist temples and other places of worship.

Similarly large majorities in most countries say that it is appropriate for non-Buddhist foreigners to marry Buddhists from their country. Adults in Sri Lanka are notably less likely to agree with this statement: Only 54% of Sri Lankan Buddhists say such marriages are appropriate, while in other countries, three-quarters or more of Buddhists take this stance.

Buddhists generally report less support for foreign non-Buddhists adopting Buddhist symbols and images. About six-in-ten Buddhists in Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand (63% each) and even fewer in Cambodia (40%) and Sri Lanka (11%) say that it is appropriate for non-Buddhists from other countries to wear images of Buddha or other Buddhist symbols. And non-Buddhists having Buddhist symbols or images tattooed on their body is even less accepted by Buddhists. Among Thai Buddhists, for example, 35% say that such tattoos are appropriate, while 60% say they are not appropriate.

CORRECTION (Sept. 28, 2023): A previous version of the text in Chapter 6 swapped the Sri Lankan and Singaporean percentages of adults who say that religious, ethnic and cultural diversity has a positive impact on their country. The charts and graphics with this data were correct. This change does not substantively affect the findings of this report.