Most Buddhists and Muslims in the countries surveyed support basing laws on religious doctrine.

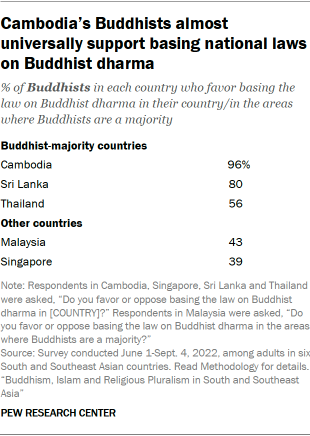

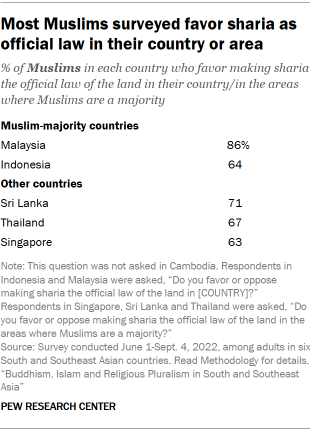

In Buddhist-majority countries – where Buddhism is embedded in the constitutions – a majority of Buddhists favor basing the law on Buddhist dharma, with support ranging from 56% of Buddhists in Thailand to nearly all in Cambodia (96%). And most Muslims in Muslim-majority countries favor making sharia the official law of the land. Furthermore, a majority of Muslims in other countries support the implementation of sharia law in the parts of their countries where Muslims are a majority. (The survey did not define what a dharma-based or sharia-based legal code would entail.)

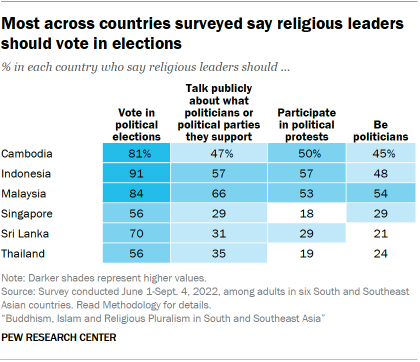

Respondents in these countries have a range of views on their preferred role for religious leaders in politics. Although most respondents agree that religious leaders should vote in political elections, opinions vary on whether they should be politicians, participate in political protests, or publicly express their political views. For example, Cambodian Buddhists are significantly more likely than Thai Buddhists to say that religious leaders should participate in political protests (50% vs. 18%) or be politicians (45% vs. 22%).

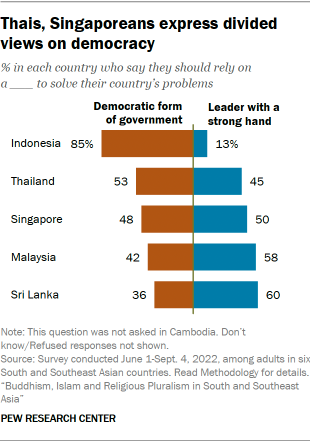

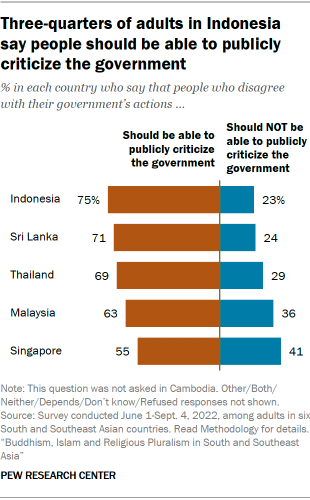

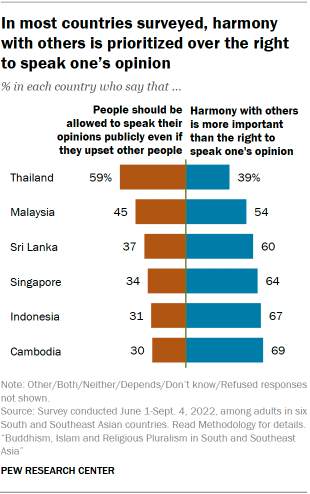

The survey asked a few other questions about politics, finding that free speech and democracy are not always widely embraced in the region. While Indonesians overwhelmingly prefer “a democratic form of government” over “a leader with a strong hand” to solve their country’s problems, half or more of respondents in Sri Lanka, Malaysia and Singapore say they would rather rely on a strong leader. And in five of the six countries, people are more likely to say that “harmony with others is more important than the right to speak one’s opinion,” rather than the opposing view that “people should be able to speak their opinions publicly even if they upset other people.”

At the same time, majorities generally support the right to publicly criticize the government. For instance, even though six-in-ten Sri Lankans prefer a leader with a strong hand to solve problems, an even larger majority (71%) say people who disagree with the government’s actions should be able to publicly criticize the government. Notably, Sri Lanka experienced widespread protests against the government while the survey was taking place.

Differences between religious groups on these questions about democracy and free speech are muted, although there are much bigger gaps by religion when it comes to views toward same-sex marriage, with Buddhists generally much more likely than Muslims to say gay and lesbian couples should be able to marry legally.

Should religion influence national laws?

The survey asked Buddhist and Muslim respondents whether they favor basing the law in their country (or the areas where their group is a majority) on their respective religions. Most Buddhists in the Buddhist-majority countries studied and most Muslims in the Muslim-majority countries say the law in their countries should be based on their religious teachings.

Nearly all Cambodian Buddhists (96%) favor basing their law on Buddhist dharma – a wide-ranging concept that includes the knowledge, doctrines and practices stemming from Buddha’s teachings. A large majority of Sri Lankan Buddhists (80%) feel the same way. Buddhists in Thailand are less likely to support basing Thai law on Buddhist dharma, yet more than half (56%) still express this view. The national constitutions of these three countries already establish a special role for Buddhism.

In countries where Buddhists are not a majority, Buddhists are less supportive of dharma-based laws. Fewer than half of Malaysian Buddhists (43%) support basing the law on Buddhist dharma in the areas where Buddhists are a majority, and a similar share of Singaporean Buddhists (39%) say that Singapore’s laws should be based on dharma. According to 2020 census figures, 19% of Malaysians and 31% of Singaporeans are Buddhist.

An overwhelming majority of Muslims in Malaysia (86%), where Islam is the official religion, favor making sharia the official law of the land. Nearly two-thirds of Indonesian Muslims also support establishing sharia. While Indonesia’s constitution does not favor Islam, certain areas of the country have enacted elements of Islamic law.

Support for sharia also is widespread among Muslims in the study’s Muslim-minority countries. A majority of Muslims in Sri Lanka (71%), Thailand (67%) and Singapore (63%) back sharia as the official law of the land in the areas where Muslims are a majority.

In these countries, Muslim citizens have access to Islamic law in limited circumstances. In Thailand, Muslims living in four southern provinces (where Muslims are a majority) can use Islamic law for family disputes. Muslims in Sri Lanka can settle family and inheritance cases through a special legal system that includes aspects of sharia. Similarly, a Sharia Court in Singapore can hear and decide on cases related to family affairs.

Among Muslims in Malaysia and Buddhists in Sri Lanka and Thailand, respondents who pray daily are moderately more likely than others to want to base their country’s laws on religious teachings. However, Muslims in Indonesia who pray daily are about as likely as those who pray less often to support instituting sharia in Indonesia.

The role of religious leaders in politics

The survey asked all respondents whether they support the involvement of religious leaders in political life – specifically, whether religious leaders should vote in political elections, talk publicly about what politicians or political parties they support, participate in political protests, or be politicians.

Countries have varying traditions around the involvement of religious leaders in political life. In Thailand, for example, monks are not allowed to vote, take part in protests or express their political opinions. By contrast, Sri Lanka has a long tradition of monks participating in politics, including holding positions in Parliament.

While respondents across various countries and religions generally say that religious leaders should vote in political elections, views are mixed when it comes to the other three political activities.

Respondents in Cambodia, Indonesia and Malaysia generally are the most supportive of political involvement by religious leaders. On the other hand, most adults in Sri Lanka, Singapore and Thailand are against the active participation of religious leaders in political life. For example, fewer than a third of Singaporeans (29%), Thais (24%) and Sri Lankans (21%) believe religious leaders should be politicians – significantly smaller than the shares of adults in Cambodia (45%), Indonesia (48%) and Malaysia (54%) who take the same position.

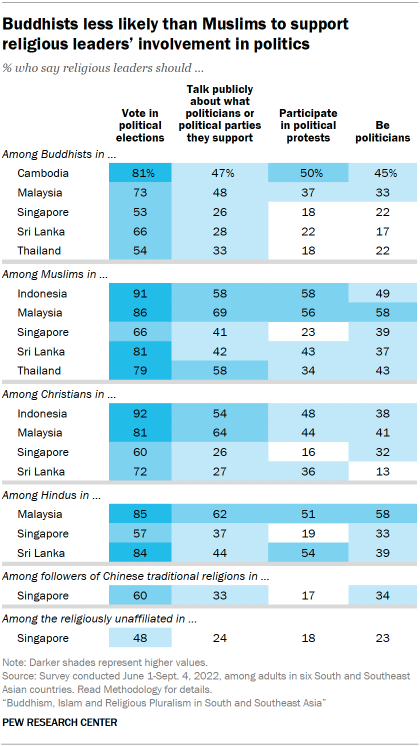

In the countries surveyed, Muslims are more likely than Buddhists to say religious leaders should vote in political elections. For instance, in Sri Lanka, a large majority of Muslims support religious leaders voting (81%), compared with a smaller majority of Buddhists (66%) who share this view.

Nevertheless, more than half of respondents across all religious groups – with the exception of religiously unaffiliated Singaporeans (48%) – say religious leaders should vote.

Overall, public support is lower for the other types of political engagements by religious leaders. And Muslims generally are more supportive than Buddhists of these behaviors.

For example, fewer than half of Buddhists in all countries surveyed think religious leaders should be politicians. Muslims are more supportive of religious leaders being politicians, including a majority of Malaysian Muslims (58%) who say this.

In general, adults who have received more education are less likely to say religious leaders should be politicians or talk publicly about what politicians or political parties they support. For example, 39% of Indonesians with at least a secondary education feel religious leaders should be politicians, while 52% of Indonesians with less education feel this way.

And people who are more religious – that is, those who say religion is very important in their lives – are slightly more inclined than others to believe that religious leaders should publicly support political parties or candidates.

Strong leader or democratic government?

The survey asked respondents to choose between a “democratic form of government” or a “leader with a strong hand” as the better option to solve their country’s problems. While it is possible for a democratically elected leader to rule with a strong hand, by forcing a choice between these two options, the question aimed to capture respondents’ overall preference for what type of government is best.

Indonesia is the only country in the survey where an overwhelming majority (85%) supports democracy as the best form of government to solve the country’s problems. Roughly half of adults in Thailand (53%) and Singapore (48%) also prefer a democratic form of government. In Malaysia and Sri Lanka, however, most people would rely on a leader with a strong hand to solve the country’s problems (58% and 60%, respectively).16

Across the surveyed countries, adults with more education generally are more likely than those with less education to prefer a democratic form of government. And adults younger than 35 tend to be more likely than their elders to prefer democracy over a strong leader.

Within countries, differences between religious groups on this question are modest.

Views toward criticism of government, free speech and harmony

The survey asked two questions about people’s opinions on political speech and dissent: 1) whether those who disagree with the government should be able to express their criticisms publicly, and, separately, 2) whether it is better to speak one’s opinion, even if it upsets other people, or to maintain harmony with others.17

Most adults in every country where the question was asked express the view that people who disagree with the government’s actions should be able to publicly criticize the government.18 Substantial majorities in Indonesia (75%), Sri Lanka (71%) and Thailand (69%) take this position, as do 63% of Malaysians.

Singaporeans are somewhat less supportive of a right to publicly criticize the government, with 55% of adults expressing this view. (Freedom of expression and of the press are limited in Singapore, and the government has many tools to surveil the public. Scholars have noted that, in Singapore, “people often refrain from expressing their views when they believe that the government disagrees with their opinions.”)

Within Singapore, considerable differences emerge by religious group. Singaporean Christians (59%) and those with no religion (65%) are the most likely to say that people should be able to publicly criticize the government if they disagree with its actions. Those who follow traditional Chinese religions (40%) are the least supportive.

While most adults in the countries studied express the view that people should have the option to publicly criticize the government, respondents generally are less likely to say that people should exercise free speech rights if doing so would disrupt social harmony.

At least half of adults in five of the six countries surveyed take the position that “harmony with others is more important than the right to speak one’s opinion,” including around two-thirds of adults in Cambodia (69%), Indonesia (67%) and Singapore (64%).

Most Thais (59%) take the opposite stance, that “people should be allowed to speak their opinions publicly even if they upset other people.” But Muslims in Thailand differ from the Buddhist majority on this question. Roughly half of Thai Muslims (52%) say that harmony with others is more important than the right to speak one’s opinion, compared with 38% of Thai Buddhists who take the same stance.

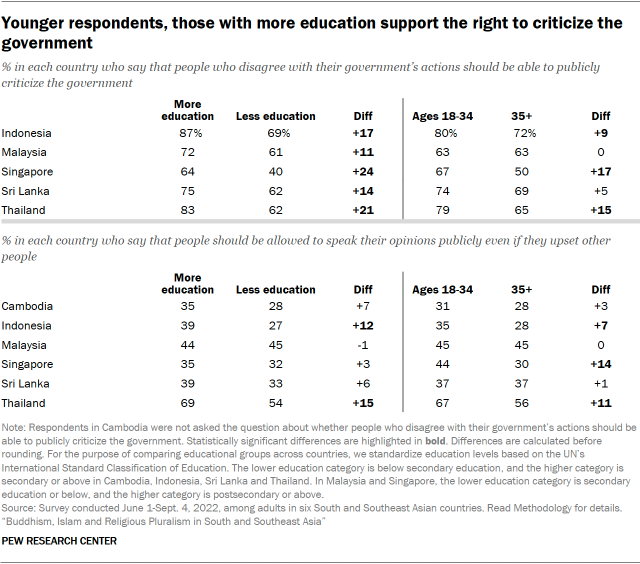

Across all five countries where the question about criticizing the government was asked, respondents with higher levels of education are more likely than those with less education to support the right to publicly criticize the government.

In Malaysia, for instance, 72% of individuals with a college education say that people who disagree with the government’s actions should be able to publicly criticize the government, compared with 61% of Malaysians with less education. The education gap is even more pronounced in Singapore, where 64% of college-educated respondents support the right to criticize the government, compared with 40% of those with less education.

Younger adults (ages 18 to 34) also are more likely than older people to back the right to public government criticism in Singapore, Thailand and Indonesia. Similarly, younger adults in these three countries are more likely than older adults to say that people should be able to speak their opinions even if they upset other people. For example, 35% of younger Indonesians share this view, while somewhat fewer Indonesians ages 35 and older support free expression even at the expense of social harmony (28%).

Views on legalization of same-sex marriage

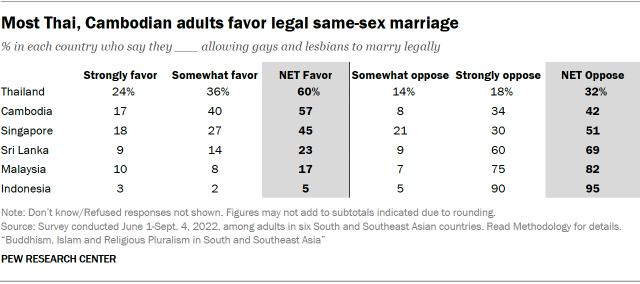

As of 2023, same-sex marriage is not legal in any of the six surveyed countries, although Thailand was taking initial legislative steps toward approving same-sex unions while the survey was in the field. A majority of Thai adults strongly or somewhat favor allowing gays and lesbians to marry legally (60%). Neighboring Cambodia is the only other surveyed country where a majority takes this stance (57%).

By contrast, large majorities of the public in Indonesia (95%), Malaysia (82%) and Sri Lanka (69%) oppose legal same-sex marriage. Singaporeans are more evenly divided (45% favor vs. 51% oppose). Shortly after the survey fieldwork concluded, sex between men was decriminalized in Singapore, though the constitution was amended at the same time to limit future avenues for legalizing same-sex marriage. And, in May 2023, Sri Lanka’s Supreme Court also opened the door to decriminalizing homosexuality.

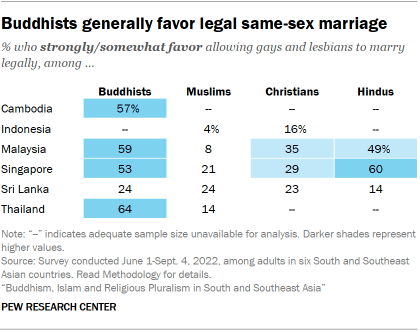

Overall, Buddhists are much more likely than Muslims and Christians to support gays and lesbians marrying legally. Half or more of Buddhists in Thailand (64%), Malaysia (59%), Cambodia (57%) and Singapore (53%) take this position, with Sri Lanka (24%) the only exception.

In Singapore, those without a religious affiliation (62%) are more likely than Buddhists to say they favor the legalization of same-sex marriage.

By contrast, no more than about a quarter of Muslims in any country surveyed support legal same-sex marriage, including just 4% in Indonesia. Support for allowing gay and lesbian couples to marry is somewhat more common among Christians, but still no higher than 35% in any of the countries studied.

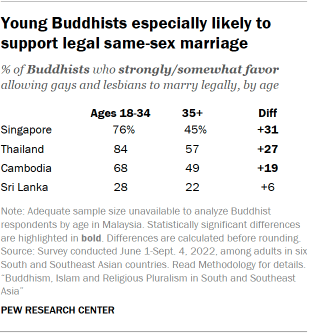

Younger Buddhists (ages 18 to 34) are much more likely than their elders to support legal same-sex marriage. For instance, while 76% of younger Buddhists in Singapore say they strongly or somewhat favor allowing gays and lesbians to marry legally, 45% of older Buddhists in the country take this position.

Buddhists who say religion is very important in their lives are less likely to support legal same-sex marriage. And Buddhist men tend to be less likely than Buddhist women to hold this view.