The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is officially atheist, and its members are not permitted to join any religion. The party’s attitude aligns with the Marxist view that religion is a temporary historical phenomenon that will disappear as societies advance. Although this stance has not changed in the seven decades since the state’s founding, policies on the ground have constantly evolved. For example, the current constitution of the People’s Republic of China, adopted in 1982, states that ordinary Chinese citizens enjoy “freedom of religious beliefs” (zongjiao xinyang ziyou 宗教信仰自由).

1950s: Transition to socialism

After then-Chairman Mao Zedong’s CCP established the People’s Republic of China in 1949, religion – “the opiate of the masses,” according to Karl Marx – quickly became a target.

Political leaders at the time described religion as being linked to “foreign cultural imperialism,” “feudalism” and “superstition.” Religious groups were persecuted across the board: Buddhist monks for participating in a feudal regime that supported them with donations, and Christians for their ties to foreign missionaries and the Vatican.89

In the 1950s, as a part of a nationalization campaign, the government confiscated many temples, churches and mosques for secular use.90 Foreign missionaries were deported, and churches were urged to cut ties with outside organizations, including the Vatican.91

Meanwhile, the government established a Religious Affairs Bureau to oversee religious activities and promoted the Three-Self Patriotic Movement (self-government, self-support and self-propagation) for religious groups. By the late 1950s, patriotic religious associations had been formed to manage and monitor each of five religions – Buddhism (1953), Islam (1953), Protestantism (1954), Taoism (1957) and Catholicism (1957).

1966-1976: Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution

During the Cultural Revolution, religion became a target of Mao’s campaign to eliminate the “Four Olds” – “old things, old ideas, old customs and old habits.” All religious activities were banned, and religious personnel were persecuted. Paramilitary Red Guards attacked or destroyed many temples, shrines, churches and mosques, and some were abandoned, closed or confiscated.92 Chinese people who wanted to maintain their faith practiced in secret.

1982: Document 19

State policy toward religion shifted after Mao’s death in 1976. In 1982, the Central Committee of the CCP issued a manifesto that came to be known as Document 19, in which the CCP acknowledged the complexity associated with religion and granted its citizens freedom of religious belief (zongjiao xinyang ziyou).

The document also set boundaries for religious freedom by allowing only “normal” religious activities (though it left “normal” undefined) and banning religious education among minors. In addition, the CCP banned party members from practicing or believing in religion and stressed the importance of strengthening atheist education among China’s citizens.

In the decades following the Cultural Revolution, the government focused on economic development. Religious activity began to revive. Temples, mosques and churches closed or confiscated during the Cultural Revolution were allowed to reopen, while those that had been damaged or destroyed were repaired or rebuilt – some with government funds. Buddhist temple construction and activities significantly benefited, as authorities hoped religious tourism would boost the economy.93

Government officials in some instances even tolerated religious groups or activities outside the legally sanctioned system. For instance, the popular pastor Samuel Lamb (Lin Xiangao), who led a large underground Protestant church in Guangdong province, was generally left to operate freely in the 1980s.

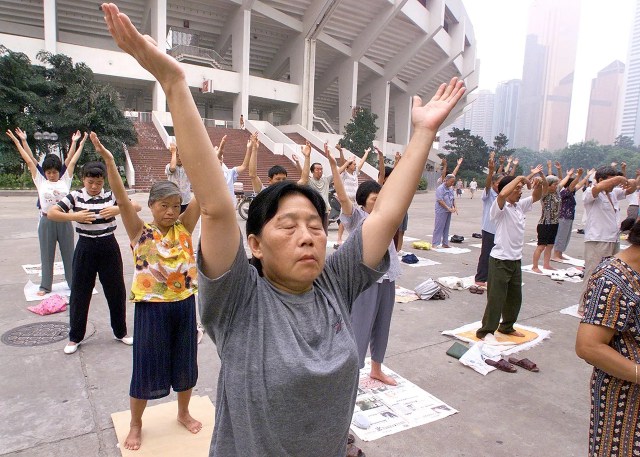

In this relaxed climate for religion, the traditional practice of Qigong (气功) became widespread, by some estimates attracting more than 60 million practitioners across China by the late 1980s. Qigong – a set of exercises and meditative practices related to Buddhism and Taoism – was openly endorsed for its purported health benefits and promoted by high-level officials and leading scientists. Despite its spiritual roots, authorities did not view Qigong as superstition or even religion, instead declaring it a “precious scientific heritage.”94 During this time, many new Qigong masters, who claimed to have supernatural power (teyi gongneng 特异功能), emerged. So did new forms of Qigong that incorporated elements of folk, Taoist and Buddhist traditions.

1989: Tiananmen Square protests

The student-led, pro-democracy protests in Tiananmen Square, Beijing, that were ended violently by the government led to tighter regulation in all spheres of life.95 Authorities cracked down on religious groups outside the official system and arrested their leaders and members, significantly affecting underground churches.

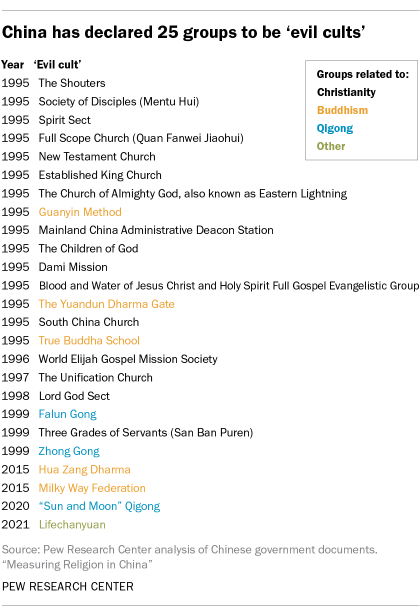

In 1995, China’s leadership labeled 15 religious groups, including 12 with Christian roots, as “evil cults” and banned them. Soon after, it also outlawed some Qigong groups.96

Falun Gong (法轮功), a spiritual group that emerged in the early 1990s, was officially denounced as an “evil cult” in 1999, following the Zhongnanhai Incident, when thousands of Falun Gong practitioners protested outside the leadership compound of the CCP central committee, demanding official recognition. At the time, Falun Gong claimed to have 70 million adherents in China.

Since then, Falun Gong has been treated harshly. The government established the Office for Preventing and Dealing with the Evil Cult Issue, also known as the 610 Office, to crack down on Falun Gong nationwide.

2004: ‘Regulations on Religious Affairs’

While the government cracked down on these new religious groups, the state policy on five recognized religions shifted slightly, becoming relatively lenient as political leaders emphasized pushing them to adapt to the socialist society. In 2004, the State Council issued a set of “Regulations on Religious Affairs.”

The document listed rules for religious personnel, sites and activities. It specified that local religious bureaus could exercise legal and administrative authority over religious affairs, such as closing unregistered churches and confiscating properties.

However, the regulations were not always strictly enforced at the local level. Observers say that local authorities managed religious practices with “one eye open and one eye closed” and tolerated “illegal” religious activities as long as “no lines have been crossed.”97

In other words, local regulations on religious activities under then-President Hu Jintao’s leadership (2003-2013) remained essentially unchanged from the previous decade, as Hu believed religion could contribute to a harmonious society.98

2015: Xi Jinping’s ‘Sinicization campaign’

Since Xi Jinping came to power as the general secretary of the CCP in 2012 and officially took office as China’s president in 2013, he has followed a new strategy on religion.

Xi summarized his approach to religious groups in a speech in 2015 that called for the “Sinicization of religions,” urging all religious groups in China to adapt to socialism by integrating their doctrines, customs and morality with Chinese culture. The campaign particularly affects so-called “foreign” religions. Leaders of Protestantism, Catholicism and Islam are expected to align their teachings and customs with Chinese traditions and “pledge loyalty” to the state.

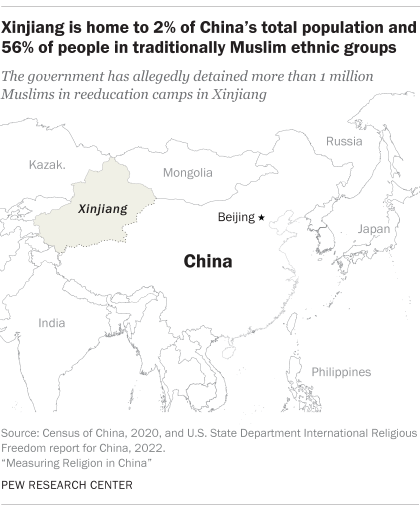

His strategy is two-pronged: On the one hand, the government has tightened controls on Islam and Christianity. China’s policy toward Muslims includes the detention of Uyghurs in Xinjiang and a crackdown on underground Quran study groups.

Toward Protestants, the government has reinforced its ban on unauthorized worship sites, forcing house churches to join a state-run association and detaining religious leaders who refuse to cooperate.

Similarly, “underground” Catholics have faced increased harassment, especially after the Beijing-Vatican deal in 2018, which paved the way for the Chinese government and the Holy See to cooperate in appointing bishops.

On the other hand, as Xi has promoted traditional Chinese culture, activities tied to Confucianism, Taoism and Buddhism have continued to experience relative leniency.

For instance, the government has allocated funds to protect and repair cultural relics, including Buddhist grottoes, and has encouraged Taoists to contribute to constructing an “ecological civilization.”

This is not to say that Confucianism, Taoism and Buddhism have been spared from government control.

These groups, too, have faced increased scrutiny, though to a lesser extent than Islam and Christianity. For example, the government has enacted measures to tackle “outstanding problems” in the Buddhist and Taoist communities, including alleged commercialization, misconduct by Buddhist leaders, and fake monks.

The State Council updated its “Regulations on Religious Affairs” in 2017. Since then, local authorities have intensified efforts to investigate, register and manage unauthorized places of assembly, such as house churches.

In 2018, the State Administration for Religious Affairs (SARA), which previously enforced religious policy relatively independently, was renamed the National Religious Affairs Administration and placed under the direct supervision of the United Front Work Department (UFWD) – a powerful agency responsible for neutralizing or stifling potential opposition groups that is sometimes referred to as the CCP’s “magic weapon” – signaling a tightening of the party’s grip on religion. SARA’s local offices were subsequently absorbed into the UFWD.

In 2021, the government issued a new regulation on online religious content, banning unauthorized religious activities and unregistered religious groups from sharing religious content online.