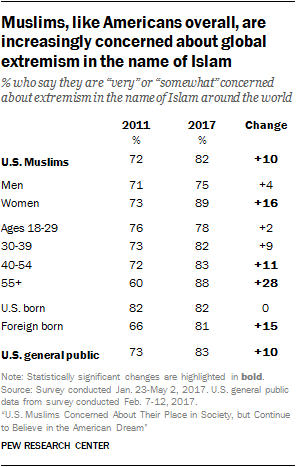

Since 2011, U.S. Muslims have become more concerned about extremism in the name of Islam around the world. At the same time, most believe there is little support for extremism within their own community, even as the general public disagrees.

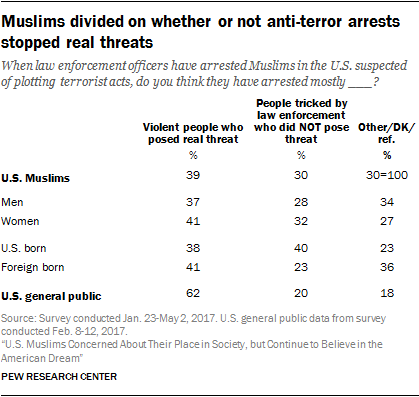

Indeed, Muslims are conflicted about the arrests of Muslims in the U.S. who are suspected of plotting terrorist acts. Some believe these arrests have captured violent people who posed a real threat, but a considerable share think the arrests have picked up people who were tricked by law enforcement into plotting a violent act and never posed a real threat.

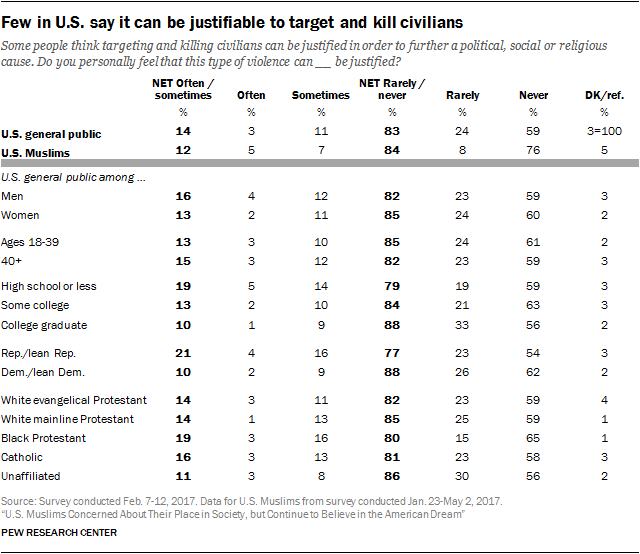

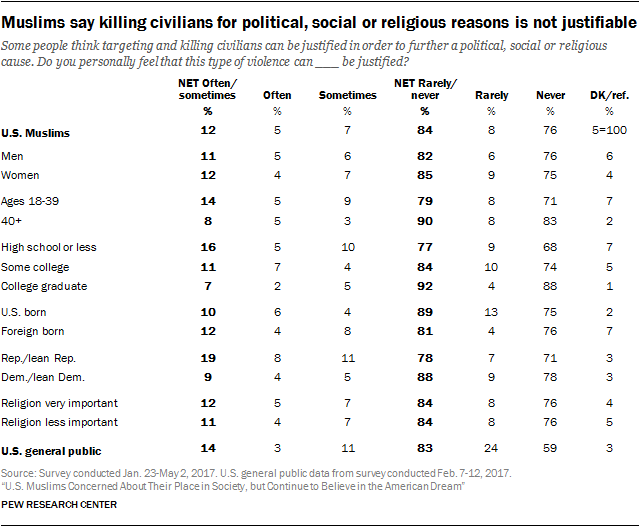

This chapter also compares the views of Muslims with those of the general public about whether killing civilians for political, social or religious causes can be justified. Large majorities of both groups reject the targeting and killing of civilians for these reasons.

Concerns grow over extremism in the name of Islam

Since 2011, Muslim Americans have become increasingly concerned about extremism in the name of Islam around the world, as have those in the U.S. public as a whole. Currently, 82% of Muslims say they are either “very” (66%) or “somewhat” (16%) concerned about extremism in the name of Islam around the world, up from 72% in 2011. (In 2007, 77% of Muslims said they were very or somewhat concerned.)

Among the U.S. public as a whole, a similar share (83%) say they are at least somewhat concerned about extremism in the name of Islam around the world, although Muslims are more likely than Americans overall to say they are very concerned about extremism in the name of Islam around the world (49% of U.S. adults say this).

The increased concern about global extremism is especially pronounced among Muslim women, older Muslims and Muslim immigrants. Currently, almost nine-in-ten Muslim women (89%) say they are at least somewhat concerned about extremism in the name of Islam around the world, up 16 percentage points since 2011. Among Muslims ages 55 and older, 88% express concern about global extremism in the name of Islam (including 82% who are very concerned), up 28 points since 2011. And among foreign-born Muslims, the share expressing concern about this issue has jumped 15 points over the last six years (from 66% to 81%).

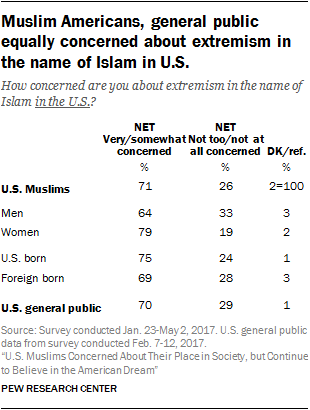

Muslims are somewhat less concerned about extremism in the name of Islam in the U.S. than they are about extremism in the name of Islam around the world, which is also the case for the U.S. public overall. Still, most Muslims (71%) are at least somewhat concerned about extremism in the name of Islam in the U.S., including roughly half (49%) who are very concerned.

Again, women are somewhat more concerned than men about extremism in the U.S., but U.S.-born and foreign-born Muslims express similar levels of concern.

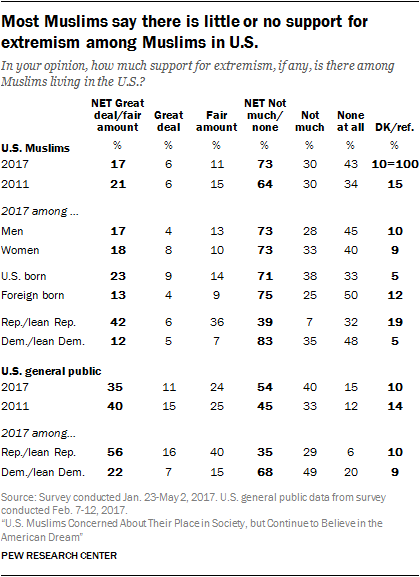

Muslims see little support for extremism in the Muslim American community

Despite their concerns about extremism in the name of Islam in the U.S., about three-quarters of Muslim Americans say there is either little or no support for extremism within the American Muslim community, including 30% who say there is “not much” support for extremism and 43% who say there is “none at all.” Just 17% say there is either a “great deal” (6%) or a “fair amount” (11%) of support for extremism. A bigger share of the U.S. public overall (35%) believes there is at least a fair amount of support for extremism among Muslims living in the U.S.

In the general public, Republicans and those who lean toward the GOP are much more likely than Democrats and Democratic leaners to say there is significant support for extremism among Muslims in the U.S., and the same pattern is seen within the U.S. Muslim community. Among the 13% of Muslims who identify with or lean toward the GOP, four-in-ten (42%) say there is a great deal or a fair amount of extremism among American Muslims, compared with just 12% of Muslim Democrats and 22% of Democrats overall who say this.

Concerns about entrapment of Muslims as part of anti-terror efforts

American Muslims are conflicted about the arrests of Muslims in the U.S. suspected of plotting terrorist acts. While four-in-ten Muslims think law enforcement officials in these cases mostly arrest violent people who pose a real threat (39%), three-in-ten think they mostly arrest people who are tricked by law enforcement and who do not pose a real threat (30%). Another 30% volunteer that “it depends” or offer another response or no opinion.31 Compared with Muslims, the general public is much less ambivalent: 62% of U.S. adults say those arrested are violent people, while 20% say authorities mostly arrest people who are tricked by law enforcement and do not pose a real threat.

Muslim Americans even more likely than general public to say targeting and killing civilians is never justified

In an attempt to gauge views about violence against civilians – not only among Muslims, but also among Americans overall – Pew Research Center asked a new question in this survey. The survey asked whether “targeting and killing civilians can be justified in order to further a political, social or religious cause.”

Although both Muslim Americans and the U.S. public as a whole overwhelmingly reject violence against civilians, Muslims are more likely to say such actions can never be justified. Three-quarters of U.S. Muslims (76%) say this, compared with 59% of the general public. Similar shares of Muslims (12%) and all U.S. adults (14%) say targeting and killing civilians can “often” or “sometimes” be justified.

Muslims who say religion is very important in their lives and those who say religion is less important to them express similar views on this question.

In their own words: What Muslims said about extremism and violence

[violence against civilians]

[has]

[anybody]

“Never. I see the world from my own moral and religious standpoint: If you have a beef with someone, the only way you can justify taking to arms is if you’re attacked first. And then, according to Muslim law, I’m only talking about governments … to defend their population or their borders. My faith is a completely a nonviolent faith. I don’t support the use of IEDs or of warfare by shadow fighters who are not part of a government. As an American, I have a huge problem with anyone choosing to take up arms against our country. At the same time, I’m critical of our government. The way we use drones casts an ugly glow over our foreign policy. It doesn’t make things better or foster togetherness.” – Muslim woman in her 40s

“Our religion teaches us never to kill or to hurt others. Islam teaches us peace, not violence. … I just want to say that all Muslims are not bad people. Some might be psychos are something like that. But people need to know that real Islam is against violence. … Real Muslims are not violent or bad.” – Muslim woman over 60

This new, more general question about violence against civilians was designed to be asked of all U.S. adults, to help put findings about Muslims into context. In previous surveys of Muslim Americans, Pew Research Center asked Muslims whether targeting and killing civilians could be justified in defense of Islam, which made comparisons with non-Muslims impossible.

The new question finds that among the general public, Americans with a high school degree or less education are somewhat more likely than those with more education to say there are circumstances in which violence against civilians can be justified. In addition, Republicans and those who lean toward the GOP are more likely than Democrats to say such tactics are sometimes or often justifiable.

[World War II]

Although the survey question was intended to probe the morality of targeting innocent people to advance a cause – as suicide bombers and other terrorists often do – some respondents may have interpreted it more broadly. For instance, one man in his 80s said that violence against civilians is acceptable “just in self-defense.” And another man in his 50s said: “If I’m walking along and I’m peaceful, and somebody wants to hurt me or my family because of their political, religious, social views, by all means I think … our law enforcement has every right to put them down.”