The measurement of race and ethnicity in the U.S. has evolved over the centuries, alongside changes in Americans’ views about race and the way race has come to be incorporated into the nation’s laws and policies.

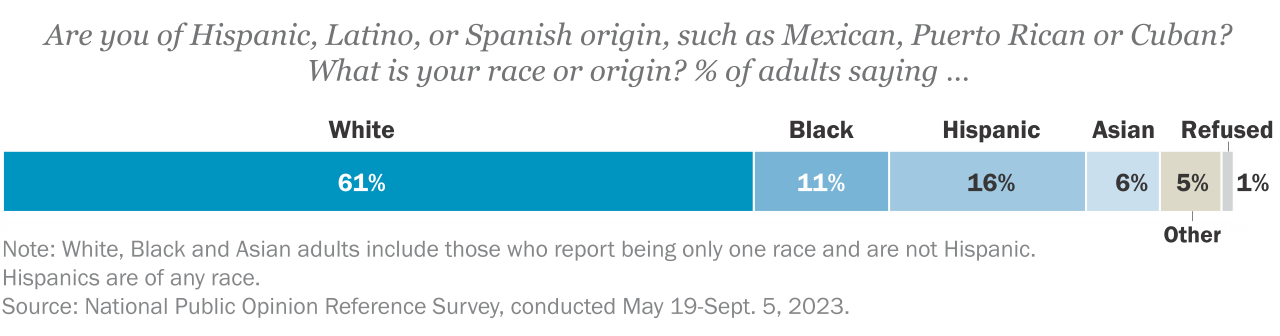

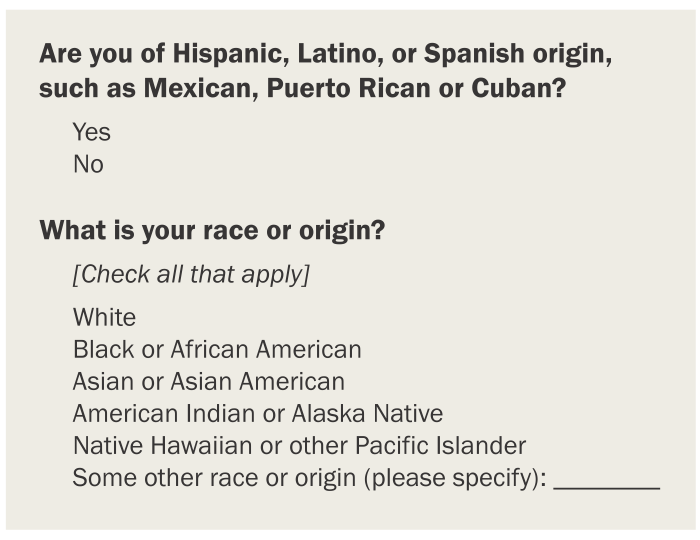

Pew Research Center uses a two-question sequence that asks first about Hispanic origin and then about race. The race question gives six options, including an open-ended one for “some other race or origin.”

Why these particular categories? And why do we ask about Hispanic or Latino origin before asking about race?

Modeling our questions after the census

The U.S. Census Bureau’s race question has changed a lot since the first census in 1790, in which the census taker placed a person into one of only three categories: 1) free White male or female, 2) all other free persons, or 3) slave.

Today’s version of the question – or, actually, two questions – is very different. Pew Research Center and many other survey organizations typically follow the U.S. Census Bureau’s lead when it comes to asking about race and ethnicity. There are several reasons for this:

- The Census Bureau aligns its question with how race and ethnicity is defined in the nation’s laws and reporting directives from the Office of Management and Budget (OMB). Results from Census Bureau surveys are often used to implement government policies that take race and ethnicity into account.

- The Census Bureau takes extraordinary care in crafting its questions, typically conducting extensive testing before settling on a version to be administered to the nation’s more than 300 million residents.

- Pew Research Center uses statistical weighting to align the demographic composition of our survey samples with the results of Census surveys. To be able to match our measurement with the Census Bureau’s, our questions must be comparable.

People completing the decennial census – and Center surveys – choose among the categories offered to them on the survey forms, but that has not always been the case. For over 150 years, most people cooperated with the census by speaking face-to-face with an enumerator, who recorded the person’s race based on their observations. This approach was simple but obviously prone to error.

Beginning in 1960, when the decennial census moved to collecting data primarily via mail-in forms, the measurement of race shifted to allowing respondents to provide their own race. This approach has persisted out of necessity now that face-to-face surveys are rare in the U.S., but also because of a cultural shift toward allowing people the autonomy to self-define many of their personal characteristics.

Yet while people can volunteer any identity they wish, how they are ultimately grouped is determined by laws and policies about the use and reporting of the data.

“Yet while people can volunteer any identity they wish, how they are ultimately grouped is determined by laws and policies about the use and reporting of the data.”

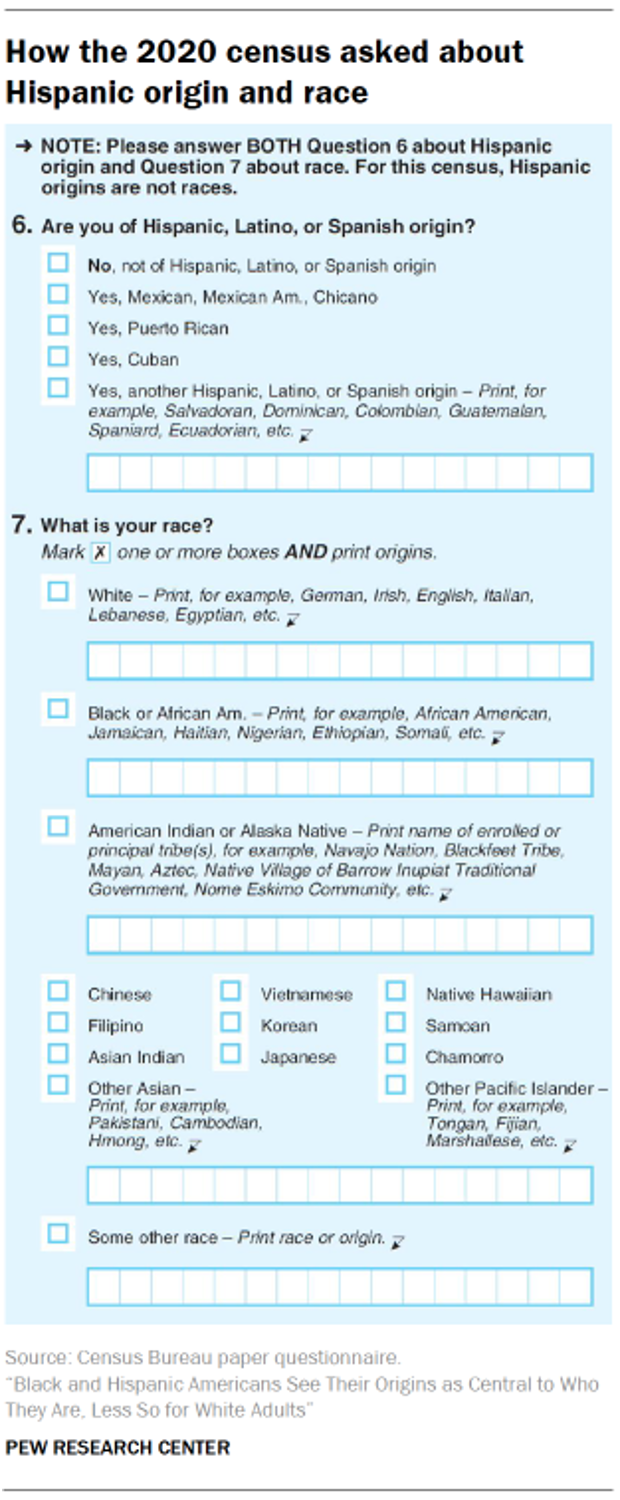

For example, by the OMB standards for reporting race and ethnicity last updated in 1997, the Census Bureau officially considers Hispanic or Latino to be an ethnicity, not a race. Respondents in the decennial census are first asked about their Hispanic, Latino or Spanish origins, before being asked a check-all-that-apply race question that does not include Hispanic or Latino as an option.

The vast majority of those who select “some other race” write in Hispanic or Latino, or a specific Hispanic or Latino origin, indicating that they consider it to be their race even though the Census Bureau does not recognize it as a race. In a 2020 Center survey, Hispanics – and U.S.-born Hispanics in particular – were more likely than White and Black adults to say the census’s race and ethnicity questions did not reflect how they see their race and origin very well.

Why is the Hispanic question asked before the race question?

The U.S. Census Bureau, following OMB guidelines, does not consider Hispanic or Latino to be a race, even though evidence suggests that many Hispanics do consider Hispanic to be their race or origin. For decades, the decennial census placed the Hispanic question further down in the questionnaire, below the race question. But researchers found high rates of leaving the question blank and theorized that people felt that they had already given their answer in the race question. The Hispanic question was moved above the race question for the first time in 2000, and more detailed instructions for answering the questions were provided. Even with the design change, in the 2020 census 42% of those who answered “yes” to the Hispanic question then said their race was “some other race” alone.

The Census Bureau has an extensive set of rules to try to place people into federally defined categories. They reassign people who write in that they are “some other race” to one of the existing race categories when possible.

For example, someone who checks “some other race” and no other category and writes in “Haitian” and “Moroccan” as their origin under some other race will be reclassified as Black and White, because the Census Bureau counts Haitian origin as Black and Middle Eastern or North African origins as White.

Other rules determine how to handle missing responses (usually assumed to be the same as another household member), conflicting race and ethnicity responses, and selecting all race categories.

Capturing multiracial identity through a check-all-that-apply approach

Another, more recent change in the measurement of race and ethnicity is allowing people to identify as two or more races.

In censuses from 1990 and earlier, enumerators and respondents had to pick one race, although categories indicating that a person was more than one race appeared on decennial census forms in 1850 through 1920. But beginning in 2000, respondents were allowed to select all that applied to them.

Measuring the size of the nation’s multiracial population is uniquely challenging and highly dependent on the question asked.

In one clear demonstration, the U.S. multiracial population appeared to more than triple – from 9 million people (2.9% of the population) in the 2010 census to 33.8 million people (10.2%) in the 2020 census. While undoubtedly the true share did increase at least somewhat in that time period, most of the dramatic jump was likely caused by changes to the Census Bureau’s question format and data cleaning procedures, which sometimes include reassigning volunteered responses to one of the existing categories.

Testing different questions about multiracial identity

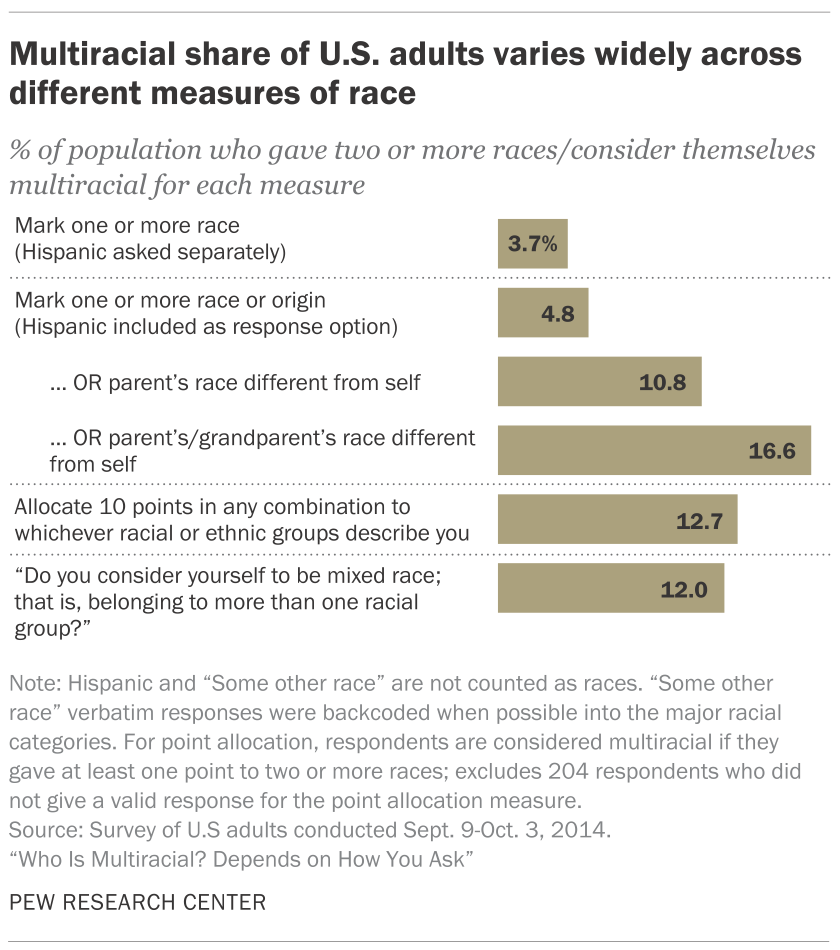

A Pew Research Center study in 2014 found that the share of the U.S. adult population that can be classified as multiracial varies from a low of 3.7% to a high of 16.6%, depending on how the question is asked and how multiracial identity is defined.

The lowest estimates were derived from the Center’s standard two-question race and ethnicity format used for telephone polls at the time, and from a question that was similar but included Hispanic or Latino as a race. For these questions, respondents who selected two or more races (not including Hispanic or some other race) were classified as multiracial.

The study also used a version of the question that asked about the race of the respondent’s parents and grandparents. When people with immediate ancestors of different races were categorized as multiracial, this produced a much higher estimate of the multiracial share of the population.

Asking respondents directly whether they considered themselves to be “mixed race; that is, belonging to more than one racial group” also resulted in a relatively high share saying “yes,” as did an approach that allowed respondents to numerically record their racial mix by allocating 10 points to whatever combination of racial groups they identified with (e.g., all 10 to one race, 5 each to two races, or some other mix).

As the multiracial and multiethnic population continues to rise in the U.S., this will become an ever more critical measurement to get right.

Alternative ways of measuring race and ethnicity

Like other identities described in this report, race and ethnicity are not cut-and-dried concepts. In fact, race and ethnicity sometimes conflate or act as proxies for other ideas such as nationality, birthplace, ancestry, culture and other people’s perceptions of someone’s identity. Pew Research Center has sought to measure some of these other concepts separately from race and ethnicity.

Our 2022-2023 survey of Asian American adults asked a series of questions related to different markers of ethnic identity. The type of question asked can make a big difference in whether someone identifies themselves as part of a certain group. Take the example of Taiwanese Americans: The 2022-2023 survey found that 126 respondents in the sample reported they were Taiwanese and no other ethnicity in a question asking about origin groups. (This narrow definition is the group that was considered Taiwanese for the purposes of analyzing the survey data.) But an additional 34 respondents said their ethnic origin was both Taiwanese and Chinese. Expanding the concept of ethnicity further, 119 respondents said Taiwan was their birthplace but did not identify ethnically as Taiwanese alone or as Taiwanese and Chinese. And another 38 people who didn’t otherwise identify as Taiwanese ethnically or by birthplace said at least one of their parents was born there.

Other Pew Research Center work has found that asking people directly if they self-identify with a certain group often yields higher size estimates for those groups than deriving identity from broader questions, like the race and ethnicity questions that appear on the census.

One example is from our work on Afro-Latinos. Far more people identify as Afro-Latino when asked directly if they consider themselves Afro-Latino than report being both Black and Hispanic on the census form.

Similarly, more people self-identify as mixed race than select multiple races in a check-all-that-apply question. Many Hispanics also consider themselves to be multiracial when asked about multiracial identity directly.

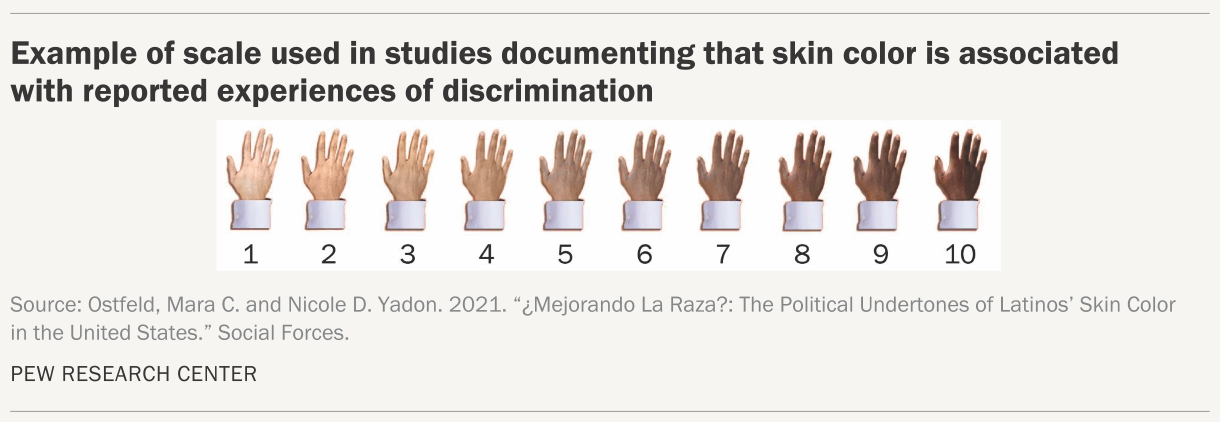

Skin color is yet another dimension related to the measurement of race and ethnicity. In a 2021 Center survey, many Hispanic adults saw skin color as having an important impact on their lives and opportunities. This study asked respondents to select the image that most resembled their own skin tone from a scale of images. Those with darker skin were more likely to report experiencing discrimination.

Racial identification is a sensitive topic for some

Race questions on surveys see relatively high rates of refusal to provide an answer compared with other demographic questions like age and gender (though they’re lower than the share who refuse to answer questions about their income).

In 2020, we conducted an experiment in which we asked respondents to describe their race and ethnicity in their own words. In this open-ended question, 18% of respondents did not provide an answer (similar to nonresponse rates for our other open-ended questions). An additional 3% gave an answer that appeared to protest the premise of the question, or an answer irrelevant to the topic of race and ethnicity:

“I believe that is the cause of most racism in the world, having to be segregated into groups.”

“I am a human like everyone else.”

“Taxpayer.”

Another 1% of respondents said their race and ethnicity was “American,” which the Census Bureau does not code as a standard race or ethnicity response, though it is a common response to questions about ancestry or ethnicity.

The remaining 79% of respondents in the Center survey provided a race, ethnicity or origin that could be mapped onto the traditional census categories.

If this reluctance to answer is due to mistrust over how the answers will be used, the concern is not necessarily unfounded. The Census Bureau is bound by law to keep all information that could be used to identify a person confidential and to use all information gathered for statistical purposes only. Under this law, someone’s personal information cannot be used against them by a court or government agency.

Yet during World War II, the Census Bureau provided the U.S. Secret Service with the names and addresses of Japanese Americans, many of whom were U.S. citizens. The government used this information to assist in locating and incarcerating these individuals. At the time, these actions were legal, as the Second War Powers Act of 1942 temporarily repealed the law requiring the Bureau to keep its records confidential.

Thinking on this topic continues to evolve

The racial and ethnic categories on the census – and thus, on surveys that try to match the census measures – have changed over time depending on the prevailing demographics and social and political attitudes. Changing racial attitudes and immigration policies led to changing terminology for Black Americans and other groups, as well as the addition of categories for Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, Native Americans, and Hispanic Americans.

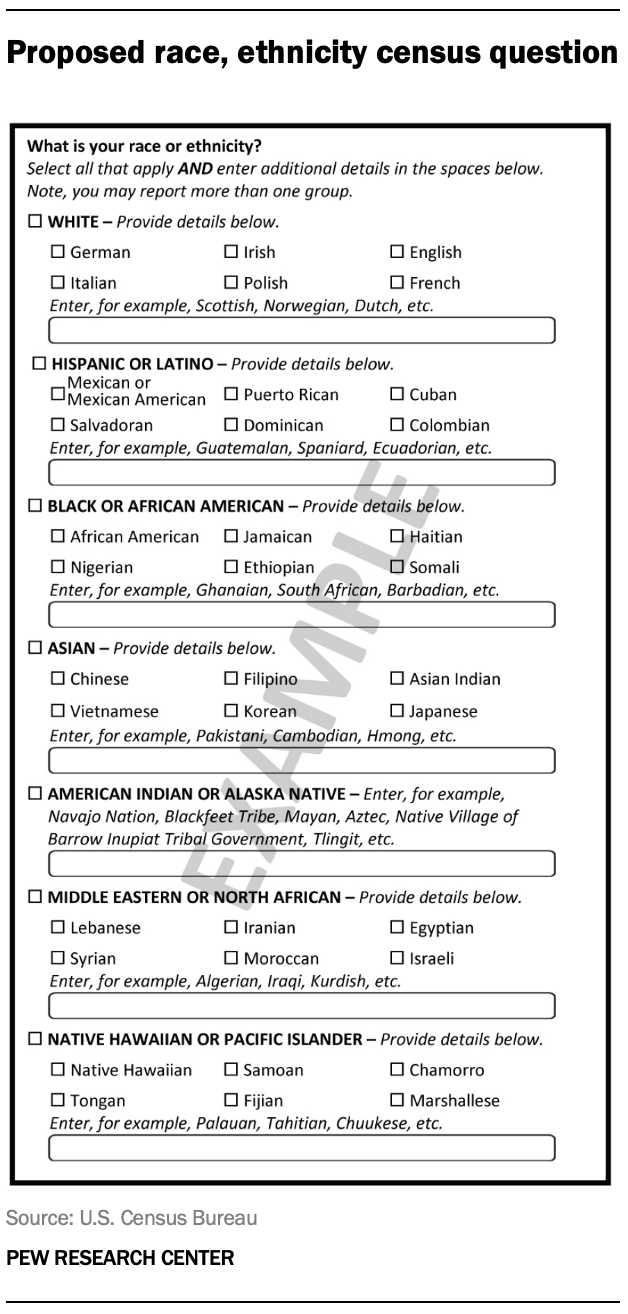

This process of change continues. The federal government has proposed updates to the race and ethnicity measures on the census and other federal surveys. One notable change under consideration is combining race and Hispanic origin into a single question so that respondents have the option of selecting Hispanic alone, without selecting one of the current race categories.

And following years of urging by activists, the government is proposing an option for Middle Eastern or North African origins (often abbreviated as MENA) rather than defining MENA origins as White. Whether these changes will ultimately be adopted remains to be seen.