Respondents’ thoughts

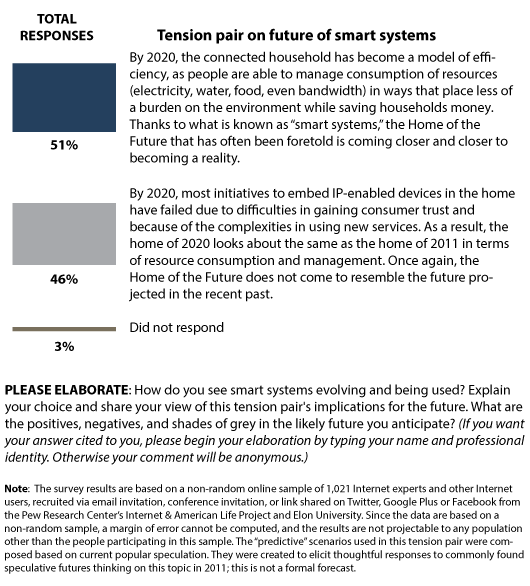

About half of survey respondents selected the more upbeat scenario positing that a significant number of the features of the Home of the Future might finally arrive by 2020.

The respondents who said the scenario will not unfold by 2020 said it is still too soon for smart systems to become deeply rooted and they spelled out a number of reasons why. Steve Jones, distinguished professor of communication at the University of Illinois-Chicago and a founding leader of the Association of Internet Researchers, reflected the thoughts of many of the most clued-in survey participants when he said, “We should be much farther along with this than we are, but one reason we are not is expense, another reason is difficulty of use, and yet another reason is difficulty in gaining public understanding of the cost versus benefit of making and implementing smarter in-home devices and systems.”

Many participants cited iconic images from the pop culture hall of fame in their answers, sometimes in all seriousness and sometimes tongue-in-cheek. Among the most common points of reference were Walt Disney’s future visions, the animated television series The Jetsons, the “talking” refrigerator that orders items for you (commonly used as an example in popular media), and the jetpack. It seems a number of people are unhappy over the fact that they can’t jet off affordably on a whim. “I await my jetpack,” said Paul Jones, a clinical associate professor at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill. “While I’m waiting, my home is much smarter, as are my car, my fridge, and my lawn care. The pace of growth in smart systems for enhancing performance continues apace.”

After being asked to choose one of the two 2020 scenarios presented in this survey question, respondents were also asked to elaborate on their answers: “How do you see ‘smart systems’ evolving and being used? Explain your choice and share your view of this tension pair’s implications for the future. What are the positives, negatives, and shades of grey in the likely future you anticipate?” This report is built around those written answers, which tended to focus on problems implementing smart systems more than they cited the benefits that could emerge.

Following is a selection from the hundreds of written responses survey participants shared when answering this question. About half of the expert survey respondents elected to remain anonymous, not taking credit for their remarks. Because people’s expertise is an important element of their participation in the conversation, the formal report primarily includes the comments of those who took credit for what they said. The full set of expert responses, anonymous and not, can be found online at http://www.elon.edu/predictions. The selected statements that follow here are grouped under headings that indicate some of the major themes emerging from the overall responses. The varied and conflicting headings indicate the wide range of opinions found in respondents’ reflective replies.

There’s movement toward such systems, but they are complicated and they may not come together anytime soon

Many survey respondents noted that getting smart systems to work correctly and efficiently for everyone can be quite difficult. “I’ve actually worked with smart grid and similar projects,” said Dave Burstein, editor of DSL Prime and Fast Net News. “The results, while real, are not even close to the optimistic scenario here.” An anonymous respondent wrote, “No one’s figured out how to do much usefully with home automation/monitoring. We will go a long way before some code acts like the butler of yore.”

Bruce Nordman, a research scientist at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and leader with the Internet Engineering Task Force, noted that standards and conventions must first be agreed upon and established, and he expects change over the next few years in regard to the approaches taken. “This directly relates to my area of work,” he said. “Progress today is impeded by the notion of the smart grid, which posits that the electricity grid should be involved in details of building operation. By 2020, this will be seen as a historical oddity, like the term ‘information superhighway’ for describing the Internet. The word ‘smart’ will be similarly in discredit. ‘Building networks’ will be a widespread term for the networking of physical-world-relevant devices (including IT devices like displays, cameras, and input devices that are physically relevant even as they are principally concerned with information). A key issue will be to develop new conventions for interacting with these devices and for establishing standard expectations for how devices should behave in response to their increasing access to information about people, the environment, and other devices in their vicinity. Establishing such conventions is part of my work.”

Jeff Jarvis, director of the Tow-Knight Center for Entrepreneurial Journalism at the City University of New York Graduate School of Journalism, has faith that the complexities will eventually be overcome and the smart home will be affordable. “The main failure with connected systems and smart homes is the fact that there have been no solid communication standards for connecting devices together,” he explained. “The other failure with connected systems is that many were built before the remote servers and the Web existed. Before then, there was no way for devices to easily communicate with each other without a lot of custom code and hardware. Researchers at PARC and others tried to usher in an era of ubiquitous computing before it was really possible and affordable. Now that the Web exists, each device only needs to be able to connect to the Web and send a message through it. Making each device Web-ready will finally allow devices to be operated from a central hub in an affordable manner. The companies that realize this will create smart houses with small, affordable chips capable of being controlled by mobile apps or SMS. The house I live in has smart technology connected by 20-year-old networks, like IRC and X-10 controllers for a total of $40 in research and development and operation cost. Everything connects through a central hub, reducing the requirement of separately coded communication channels.”

Ken Friedman, dean of the faculty of design at Swinburne University of Technology, Melbourne, Australia, said while others expect consumer adoption to be key, the spread of smart systems will not widely happen unless governments push for them. “The fate of smart systems is tied more to the will from above rather than below, as governments—especially in developing countries—try to implement an efficient infrastructure to manage energy, water, and other concerns in the face of growing populations expecting a rising standard of living,” he said. “Smart systems implemented on a mass scale from above will be the only way to ensure this. On the individual level, consumers will aid and accept the uptake of smart systems for their money-saving capabilities but will demand a certain level of flexibility based on demand and pricing (i.e., paying for more than your share.) My view is that smart systems will become simpler, and these will be embedded in increasingly easy-to-use machines and tools. If this is so, households will become more efficient and more effective.”

Charlie Firestone, executive director of the Communications and Society program at the Aspen Institute, said all of the planets have to align to make this work, and right now that’s not in sight. “Smart homes are on their way,” he explained, “but this development is being delayed. Not so much by lack of trust as by lack of alignment of the key players—utilities, ISPs, manufacturers.”

Many said smart systems are not ready to fulfill the rosy 1960s ideal. “The Home of the Future has been envisioned unrealistically for decades,” observed Lee W. McKnight, a professor of entrepreneurship and innovation at Syracuse University and founder of Wireless Grids. “The past vision of the future will not happen, but a more adaptive and responsive home will interact with its residents in new ways.”

[artificial intelligence]

President Obama’s former special assistant for science, technology, and innovation policy, Susan Crawford, is quite sure there are far too many factors working against the success of smart systems for them to evolve efficiently. “We have some impossibly intractable and well-funded boulders in our way,” she said. “The utilities want to own all the data, the carriers want to own all the data, the car industry doesn’t really want to change (which would drive a lot of smartness), and we don’t see leadership in the form of real incentives for people to change their behavior.”

“The rich, who are getting so much richer, have zero interest in saving these small amounts,” added, Crawford, now a professor at Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government. “The poor, who are getting so much poorer, are scrambling to survive and won’t want to invest, even if it would save them money in the end. The middle class, who might go for this kind of thing, is feeling hopeless. It’s impossible.”

An anonymous survey participant also pointed to corporate motivations as problematic, writing, “The biggest barrier will be profit motives. Private companies will make their systems non-compatible in order to retain market share. Just look at computer operating systems! We’d be much more efficient if they played nicely together, but they don’t. I have no reason to believe that appliances, utilities, and so forth will be any different.”

Donald G. Barnes, visiting professor at Guangxi University in China and former director of the Science Advisory Board at U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, wrote, “Barriers include the following: economic weakness, economic uncertainties, building codes, lack of standardization, lack of oversight/regulation (which actually leads to an atmosphere of business confidence), lack of tested, mature technologies, and resistance from entrenched technologies.”

An anonymous survey participant asked, “What happens when all the devices in your smart home are superseded by the next generation OS or processing hardware? How many times can you afford a new suite of every mechanical device in the house?”

Peter Mitchell, chief creative officer at Salter-Mitchell, a company that builds behavior-change programs, says we’ll only have ourselves to blame if smart systems do not gain traction. “These tools will become standard over time, but there’s a shade of grey here: A lot of people won’t use them or use them properly. The connected household will not become the model of efficiency, because many people will choose other goals. The technology won’t hold us back. We will hold ourselves back.”

[local community supported agriculture cooperative]

Smart systems are already on the way to people’s homes; we have made and will continue to make good progress

Some survey respondents who shared written elaborations tied to their scenario choices were optimistic about smart systems. “Our daily evolution will be jacked into our well-managed households, with work, education, supervision, health care, leisure happening there, virtually, or somewhere else, if we choose,” wrote an anonymous respondent. “Efficiencies will be had all around here.” Another observed: “Smart systems are already a major part of our lives (in our cars, for instance), whether we know it or not. It must become an integral part of automation in order to spur advancement.”

Stephen Masiclat, an associate professor of communications at Syracuse University, said, “The rapid spread of home Wi-Fi and other data infrastructure is the best indicator that homes will get smarter.”

Richard Titus, a venture capitalist at his own fund, Octavian Ventures, expects highly developed home connectivity will come—with good and bad results—and we’ll just have to deal with the quirks. “Our houses will be IP-connected. This is a fact. There will be some amazing products built on top of this platform, and I’m excited to see what they are. However, I suspect the system will still screw up and bring me soymilk when I really wanted goat’s milk. And it will never ever, ever be able to properly order me a dozen ripe avocados, though I’ll try again each time, as hope springs eternal.”

Robert Cannon, senior counsel for Internet law in the Federal Communications Commission’s Office of Strategic Planning and Policy Analysis, said he expects simply designed smart systems will be innovated and adopted. “We are seeing a tremendous progression in applications and data interfaces,” he said. “As those applications progress and become more integrated, and as feedback becomes more useful, the role of these applications in creating a smart house would become more compelling. The danger is that smart houses require full systems to succeed and those systems will fail—but this negative scenario seems more likely to give way to a component model where smart systems solve individual problems, not the full problem. With smart systems directed at individual solutions, they can be swapped out as needed, like changing a light bulb, and they will not bring down the whole system when there is a failure. One can imagine simple systems—such as programmable thermostats, robotic vacuums, programmable watering systems, alarm systems—all becoming progressively more compelling and driving smart houses. You then move to a smart-by-design mentality where the houses are built smart from the ground up, enabled to interoperate with new components as they arise.”

Stowe Boyd, a well-known researcher and consultant based in New York City, said the home revolution is rolling. “By 2020,” he predicted, “nearly all entertainment media will be delivered via Web, with the corresponding crash of cable companies, who become low-margin utilities. Most municipalities will take back cable- and phoneline-based Internet infrastructure by eminent domain or state legislation and provide low-cost or zero-cost connectivity to the home and business, probably supported by US government subsidies, arising from election 2012 infrastructure initiatives advanced by President Obama. Appliance manufacturers will build in Wi-Fi capabilities into printers, TVs, refrigerators, hot water heaters, air conditioners, washing machines, and clothes dryers, subsidized by energy tax credits, so that people can minimize their energy use and schedule machines to take advantage of lower-cost energy at night. Next-generation solar heating systems will also be Wi-Fi connected, relying on Web-based computing to maximize energy capture. But these will all be based on today’s houses, which are not particularly well insulated. The real breakthrough in housing will take a long time to roll out: so-called passive homes, or ultra-low-energy buildings, based on new materials and very different construction techniques. Maybe by 2040.”

Jane Vincent, visiting faculty fellow at the University of Surrey Digital World Research Centre, was among many survey participants who said the mobile apps revolution will bring positive change. “The Home of the Future will be a mobile home,” she predicted. “That is, everything that people need to be connected and efficiently manage utilities, shopping, communications, and everyday life matters will be accessible anywhere they are via a mobile device and their mobile or Wi-Fi provider. This is unlikely to be ubiquitous by 2020, and the wired up smart homes envisaged a decade ago are only practicable for new builds. In time, the only thing a household will need is broadband Wi-Fi point of connectivity. Meanwhile, smart meters and the like will only be provided on demand or if governments implement them. The technology has been around to do this for years, so only a major fuel crisis in the next five years will spur this on. The Internet will be increasingly used to get the best prices on products and delivery to the home.”

William L Schrader, independent consultant and lecturer on the future impact of the Internet, agreed. “I predict 25% of the homes in the G20 will be smart homes by 2020, controlled by a smart phone,” he said. “This not only includes thermostats and drapery closures (to cut down heat and cooling costs), but it will also assist in identifying additional savings. The smart grid will be here to manage and invoice electric use by the 15-minute period, and the pricing will be intensely managed to shift load off the peak. The same goes for water use and all resource use. The smart home, smart car, and smart phone will be one and the same for control fabric—the Internet. Encryption is a must, and there will be break-ins and thefts as there are today. People are people. America will lag the G20 (perhaps the lowest penetration in smart homes) due to a lack of political will to enable and entice people to adopt the new technology. The Internet will make it not only feasible but easy and cheaper than not doing it. That is what will drive Americans to the smart home.”

John Jackson, an officer with the Houston Police Department and active leader of Police Futurists International, wrote this scenario: “By 2020, most ‘dumb’ homes will still be in their useful lives, and many systems (air conditioning, roofs, refrigerators, washing machines, and dryers, etc.) will not be replaced. Nevertheless, by 2020 smart appliances and systems will be on their path to broad adoption. These systems will mostly be connected ‘in the background’ through wireless to the home’s wireless router. Through them, manufacturers will be able to update firmware and diagnose performance. A few appliances will be interface devices for humans to interact with the Web. The personal computer will likely disappear and be replaced by multiple devices (e.g., portables, video screens, smart furniture).”

Rich Osborne, senior IT innovator at the University of Exeter, said the economics of energy prices will be a driver of smart systems adoption. “As energy prices continue to climb ever higher it will create the financial imperative necessary for consumers to try to understand, and hence control, energy consumption. This will be the driving force behind more smart systems in the home, enabled by the rise of the Internet of Things and the smart phone. The legacy infrastructure that currently controls energy delivery may well be the biggest stumbling block, but once that becomes smarter it will enable new levels of consumer confidence, and hence desire for control over their energy consumption. This, in turn, will lead the energy companies to compete in this area, offering ever smarter systems, creating a cycle that will accelerate and eventually spread into other services.”

David D. Burstein, founder of Generation18, a youth-run voter-engagement organization, says incremental change will bring differences that we won’t see as dramatic at the time. “We’ll never see our houses work like those in The Jetsons,” he wrote. “We won’t see this as a big change that happens overnight, but a series of gradual integrations as next-generation home technology is built with some of this incorporated. Just like you have hardly any choice to buy a laptop without a webcam today, in several years people will have no choice but to buy smart-system home products.”

A key to successful adoption of smart systems will be the difference they will make in energy costs and environmental sustainability

While there’s some variability in people’s view of the timing of smart systems’ big arrival in most hyperconnected homes, most think that whenever this future arrives it will be a boost for environmental sustainability. “Homes will get more efficient because it will cost more and more to waste energy. The devices will become simpler because no one likes being outsmarted by their thermostat,” said David Weinberger, a senior researcher at Harvard University’s Berkman Center for Internet & Society.

Seth Finkelstein, professional programmer and consultant, said, “Retrofitting an existing base is a huge undertaking, and many people don’t like to deal with monitoring devices. But there will be inroads in terms of energy management, as there’s a significant number of people who see a direct benefit in lowering their energy bills by better consumption management.”

Mark Watson, senior engineer for Netflix and a leading participant in various technology groups related to the Internet (IETF, W3C), wrote, “Many more people will have greater insight into their energy use as a result of smart metering, better product labeling, and potentially (and hopefully) public policy incentives to reduce energy use (carbon tax or emissions trading). However, given the length of product replacement cycles for the major energy-consuming devices in homes, I would not expect to see many ‘homes of the future’ in the next eight years. Perhaps more devices will have easier-to-use facilities for programming them to use energy at a cheap time, but that’s about the most I expect.”

David Lowe, innovation and technology manager, National Telecommunications Cooperative Association, said, “Smart homes and smart devices will become a necessity if we are to preserve and wisely consume remaining fossil fuel resources. Global warming is a reality associated with our over-dependence on these resources. Necessity will demand more efficient utilization of our energy supplies. Smart technologies will become useful end-to-end tools in this quest.”

Laura Lee Dooley, online engagement architect and strategist for the World Resources Institute, predicted, “Homes will definitely be more efficient, but to what degree and in what ways remains to be seen. Those with financial resources will be able to invest extensively in efficiency improvements, while those with fewer resources and older homes will have some difficulty with such investments. Access to expertise on efficiency improvements and installation may be difficult in some regions; however, online do-it-yourself resources have become more accessible and authoritative, so some efficiency implementations may be unique to the individual homes.”

Duane Degler, principal consultant at Design for Context, designer of large-scale search facilities and interactive applications, wrote, “The cycle of technology embedding and innovation will become viable at some level by 2020, because manufacturers, utility operators, and local governments are pushing actively in that direction. No matter what you think about the environmental considerations, the existing wasteful cost models are not sustainable.”

Sam Punnett, president of FAD Research Inc., analyst for public and private funds supporting media and tech development, pointed out, “These systems have become a public policy imperative to address resource management and environmental concerns. I don’t see any downside. By 2020 most of these functions governing household operations will be implemented and accessible on mobile devices.”

Smarter systems will be a boon to health care, providing benefits especially for the disabled and the elderly

Survey takers generally respond most directly to the language of scenarios as outlined, and the survey question pointed people toward making observations about the benefits of connectivity in regard to resources and the environment. Moving outside this narrow frame, a number of respondents pointed out the fact that hyperconnected homes will be a boon to health care.

“In the next decade there will be huge demand for home medical alert systems, and the market will respond to that need. Health will be a bigger driver than environmental issues,” said Hal Varian, chief economist at Google.

An anonymous survey participant wrote, “Smart systems will become mandated. Electronic medical records (EMRs) are forcing this in health care. We will have laws to make it happen since we will believe the alternative is wasteful.” Another anonymous respondent noted, “All of the components are there and companies have been getting closer to making it a reality over the past five years. Smart systems will begin to be tapped for health care and home health care for the disabled and elderly.”

Carol Bond, senior lecturer in health informatics at the school of health and social care, Bornemouth University, said, “Hopefully, large organisations will focus on developing and promoting these developments. If we fail to develop the power of the Internet in these areas, we should hang our heads in shame.”

An anonymous survey participant selected the scenario that doubts rapid development of smart systems adoption in homes by 2020, writing that this opinion is proven because, “this is already evident in the more conservative descriptions of the smart grid and the reduced engagement in smart health from Google. Perhaps in 2040, these systems will rebound as efficiencies are better realized and the technology stabilizes to match specific value propositions that are socially acceptable.”

People desire simplicity, not complexity. Our grandmothers have to be able to understand these systems and they are not yet ready for that.

As technologies evolve, the user interface is key to their implementation. Many survey respondents said smart systems management and maintenance is complex, people are comfortable with the status quo, and people’s struggles with technologies already in place and the companies that provide them—DVRs, Wi-Fi hubs, home entertainment systems, cable or satellite boxes—make them wary of adding more complications to their lives.

Mike Liebhold, senior researcher and distinguished fellow at The Institute for the Future, observed, “Despite the growing availability of smart devices that report their resource utilization, people have simply too much to do already to focus scarce attention on properly managing their resource consumption in fine detail. Also, people seem to resist the idea as invasive of smart grid top-down monitoring and control of resource consumption. Conservation technologies are promising, but behavior changes will be very slow.”

Bill St. Arnaud, a research officer at CANARIE working on Canada’s next-generation Internet, noted, “The smart home will fail, not because of difficulties with IP-embedded devices, but because of lack of consumer demand. The Home of the Future will require a lot of forethought and programming of options. Think of today’s VCR or PVR. Most are too complicated for the average consumer who hardly uses a fraction of their capabilities. Consumers want simplicity not complexity. They will pay a premium for simplicity and predictability.”

Wesley George, principal engineer for the Advanced Technology Group at Time Warner Cable, has worked at the nexus of people and smart devices for years. “Smart systems are only as good as their user interface,” he said. “If they aren’t easy to use and they don’t ‘just work,’ then they will not see widespread adoption beyond those who consider themselves geeks or are interested in the green aspect of using these systems. Your grandmother has to be able to understand these systems. If she can’t, they’ll fail.”

Valerie Bock, technical services lead at Q2Learning LLC and VCB Consulting, said user interaction design is still too primitive for people to be able to feel comfortable with the technology. “We are a quarter-century into home-recorded video, and it’s still a task that is more complex than it should be,” she said. “Very simple user interface development will be critical to the acceptance of consumption regulators. I don’t see that happening in the next nine years, though I don’t really understand why better interfaces don’t exist.”

Mack Reed, principal at Factoid Labs, a consultancy on content, social engineering, design, and business analysis, argued that people will engage in the change. “The failure of smart systems to achieve full and meaningful adoption will boil down to need and interest: Do I really care (and have the tech skills) enough to link all my gadgets and appliances to determine how ‘green’ my home is? The great unwashed will not. They’ll happily use these systems and, by and large, will allow manufacturers and system operators to gather this essentially harmless, non-private data, but they just won’t care much to take advantage of it.”

Allison Mankin, an Internet and security research and development expert, pointed out that the typical kitchen has not evolved much since the 1950s. “Smart homes won’t become pervasive, unless driven by some major change in technological underpinning,” she said. “This is not because of consumer trust issues; consumers lack perspective and information and too often give trust where they should not. The reason is that it is extraordinarily hard to create really good designs for consumer items, and usages tend to shift only incrementally once established. New devices may arrive after technical breakthroughs, but the design of existing devices lingers for long periods. For instance, on the whole, the modern kitchen is surprisingly similar to the kitchen of the 1950s and earlier. Efforts to computerize and network kitchen appliances have been failing for twenty years.”

Simon Gottschalk, a professor in the department of sociology at the University of Nevada-Las Vegas, said he doubts that people will willingly buy into smart systems that require service from “unavailable, unresponsive, and increasingly expensive” “invisible expert technicians.”

“The complexity of the Home of the Future is too great for most people to efficiently manage, an inability that makes us increasingly dependent on an army of invisible expert technicians (or worse yet, pre-recorded voices that answer our anxious phone calls,)” he wrote. “As those technicians are predictably unavailable, unresponsive, and increasingly expensive, it is doubtful that people will entrust their only refuge to them and the companies they work for. In addition, the hope that the Home of the Future will impose less of a stress on the environment is predicated on the belief that the average consumer is indeed concerned about the environment and cares about its future. But such a concern and attention requires education, empathy, critical self-reflection, and attention to other peoples’/species’ needs. No aspect of everyday life (past, present, or future) can be thoroughly analyzed (or predicted) by excising it from the broader context of which it is always part.”

Natascha Karlova, PhD candidate in information science at the University of Washington, added, “I don’t want my fridge to shut down because Comcast decided to throttle my connection or because I went over my monthly allowance of data. Technology adoption and development over the next ten years will be determined by a lack of infrastructure investment and a lack of resolution on policy.”

‘It’s the economy, stupid’; smart systems are not affordable for most today, and people’s minds are on other issues when it comes to change

[Nine]

danah boyd, a senior researcher at Microsoft Research, agreed, writing, “In nine years, smart systems will still be experimental and we’ll only see them existing in reality among a handful of elites. This will be aggravated by the socio-economic instability that began in 2008 and continues to plague Western communities. Construction projects will be limited; new home owning will have decreased since the 1990s; and most people won’t have the capital to explore new living conditions. There will be serious modernization in key urban areas, particularly in corporate development, that further advance the LEED building initiatives. But not much will radically change in nine years. (I still want my jetpack, by the way. I was promised a jetpack 50 years ago.)”

Technology economics expert Jeff Eisenach, principal at Navigant Economics and formerly a senior policy expert with the U.S. Federal Trade Commission, commented, “The benefits of toaster management do not and likely never will exceed the costs. Even if the hardware, software, and communications are free, the time is not.”

Microsoft has been at the forefront of research into the technology-enabled home. Jonathan Grudin, a principal researcher for Microsoft, says the bad economy is the reason that 2020 is far too soon for development of smart systems. “If you haven’t heard, new home construction is down; house prices are down,” he said. “There will be little movement in this area by 2020. Look at automobiles—much more tractable, and there is progress, but it has been happening for a decade and it is pretty limited.”

Jon Cabiria, CEO of Teksylos Technology, a consulting company, wrote, “Companies have yet to create mass-produced products that meet the diverse needs of individuals in a way that is flexible, intuitive, and affordable. While the smart home is definitely in the future, it is not in the future of the lower or middle classes within 10 years.”

Melinda Blau, freelance journalist and author of 13 books, said, “Expense and complexity are the biggest enemies to ‘homes of the future.’ Although most people theoretically like the idea of managing their resources, building a smart home from scratch or—even more so—incorporating these systems to an existing structure is costly. Especially during economic hard times, consumers will (rightfully) question the cost/benefit ratio.”

Paul Gardner-Stephen, a telecommunications fellow at Flinders University, expressed concerns that such systems might use more energy than they save. “The fundamental problem is cost of such systems, which is driven by complexity and dependence on big-infrastructure, which will consume many of the energy and other savings that the system might otherwise deliver,” he explained. “A fresh infrastructure-free approach that allows such devices to form an in-house mesh and suitable protocols to allow the sensor data to be visualised and fed into the control systems is necessary. Even then problems of security arise.”

Marcia Richards Suelzer, senior writer and analyst at Wolters Kluwer, noted, “In the infamous words of James Carville, ‘It’s the economy, stupid.’ With so many Americans out of work (or under-employed), upside-down on their mortgages and frightened by their prospects for retirement, few are going to divert income to a cool new gadget. It’s unlikely that the effects of this economic downturn will disappear soon enough for a wave of smart systems to be installed within the next eight years.”

Bill Daul, chief collaboration officer at Social Alchemist, NextNow Network, and the NextNow Colaboratory, echoed the words of many when he said such systems will widen the digital divide and be limited to use by the economically elite. “The global rich will have smart systems. Most of the world will be more interested in trying to find food and water. Populations are not growing in so-called ‘developed’ nations, they are growing where there are little resources—water and food wars are coming. Technology won’t mean much when your family is starving.”

A key driver will be incentives or mandates; some say this is not likely to happen, at least not in the United States

Those who say that incentives or government mandates may be required for smart systems to take hold by 2020 disagreed as to whether it would actually happen. Most said that people have to be motivated by more than concern for environmental sustainability to overcome the complexities involved in the uptake of smart systems.

“The structural constraints of existing ‘dumb’ housing and the way we provision utilities makes any massive shift problematic,” noted Ted M. Coopman, lecturer, department of communication studies, San Jose State University. “An example is the pushback on the rollout of smart meters in California. If something so basic in a tech-savvy state with a history of efficiency initiatives meets resistance, what will happen in less-progressive locales? Also, there is an almost universal hatred and distrust of utility companies. The legislative will to mandate these systems—what is required to make them work—is unlikely to manifest anytime soon, if at all. Smart systems will benefit those with the knowledge to use them, and there will be a lot of great apps and devices on the market to make this happen. But short of a huge spike in utility bills, widespread adoption is unlikely. This seems like it will develop into another aspect of the financial and digital divide, where the people who need it least will have access and those who need it most won’t.”

Stephen Murphy, senior vice president for business development and digital strategy at IQ Solutions, said it will take a mandate or incentives for home energy monitoring to hit home in the US. “My 84-year-old father has an LCD display in his kitchen in the United Kingdom that measures the cost of his electricity use in pennies,” he said. “I would like an energy consumption device, too, over the surprise I get when I open my Pepco bill and learn that I have spent too many therms or watts, measures I do not fully understand. What I do understand is dollars, and I want a way to budget my energy spending. Energy monitoring tools are hard to come by in the United States, but I believe they are coming. Whether or not they come by 2020 will depend on whether energy companies are mandated or incentivized to adopt them or if consumers demand them. More education is needed about what is possible.”

Tom Franke, chief information officer for the University System of New Hampshire, said it seems the U.S. is behind. “Early, deep, and widespread adoption will be dependent on government incentives until mass adoption lowers cost,” he wrote. “It seems European and Asian nations are more inclined to move forward in this arena, while the United States is plagued with a large contingent of anti-science deniers and anti-government dogmatists. I hope I am wrong.”

An anonymous respondent wrote, “The drive to decrease energy consumption and reverse climate change will spur the introduction of smart grids and smart systems. These likely will be mandated by governments just as safety and health regulations are imposed today—for our own good.”

Another anonymous survey participant said government mandates may work to inspire the uptake of smart systems, writing, “These initiatives will continue to improve and increase in adoption, but only the most passive and mass-produced smart systems fostered by the building code or tax code will get very far. Corporations will unwarily work against them by trying to finance them on the basis of 1) baseless hype, or 2) data-gathering that too many people will resent and resist.”

Some people who already have energy-efficiency meters installed at their homes are not impressed. Donald Neal, senior research programmer at the University of Waikato, based in Hamilton, New Zealand, said he makes no use of extra features of his smart electricity meter and some new appliances in his house.

“My power company won’t give me cheaper off-peak power without an increase in peak power changes big enough to wipe out all savings,” he said. “Oh, and they believe off-peak starts at 11 p.m. We haven’t yet taken any useful step towards changes in the way resource consumption is managed.”

An anonymous respondent wrote, “PG&E is currently installing smart meters here in California. There are lots of protests in my community, and fear. The meters themselves are hard to read at the source, ugly, and invasive—I can clearly read all my neighbors’ usage.”

David Ellis, director of communication studies at York University in Toronto and author of the Life on the Broadband Internet blog, observed, “Saving money on utility bills is not a sure-fire winner unless consumers can readily connect their changed behavior to the savings—and the savings show up clearly and regularly. Utilities like electric power companies have to make major investments in research, marketing, outreach programs, and monitoring technologies to persuade their customers to conserve power.

“Even if some stakeholders are successful, there is no guarantee the systems being deployed will be interoperable and use common standards. Indeed, some suppliers, like incumbent ISPs, may have a vested interest in keeping their existing services proprietary and separate from other initiatives. This reluctance to participate in a joint effort would not be surprising in locales where there is intense intermodal competition between cable multiple system operators and incumbent telephone carriers.”

Some are concerned about centralized control and how that will supersede individual choice—and fill the coffers of service providers

Some people are suspicious of the motives and ethics behind the business practices of the powerful organizations that supply and maintain the infrastructure and services of smart systems. While a few respondents said entrenched corporations are actually slowing the development of smart systems because they are pleased with the status quo, there were more who expressed concerns that corporations will develop such systems only to gain control over resources and access to people’s data in order to pad their profits.

“We are already witnessing rejection of many smart-grid initiatives. It is perceived as an intrusion in people’s lives, as a way to shift the balance of power from the individual to the utilities,” said Christian Huitema, a distinguished engineer at Microsoft.

“Smart systems will be good in the sense that energy will be conserved,” said Brian Harvey, a lecturer at the University of California-Berkeley, “but at a huge privacy cost. And sooner or later the smart meters will start imposing rationing.”

Steven Swimmer, a consultant who previously worked in a digital leadership role for a major broadcast TV network, said there’s a power struggle now gearing up. “Connected homes will gain traction, but only when there are devices that are easy to use, easy to network, and basically plug and play,” he said. “The bigger question will be how is the hub controlled? Will it be via a home-based computer, a set-top media box, a black box, or a purely cloud-based system? Expect large battles for companies to try to own this space by offering free or subsidized devices and/or apps. Will it be your phone company, your cable/satellite company, Google, Microsoft, Amazon, Apple, Cisco, or some other big player?”

P.F. Anderson, emerging technologies librarian at the University of Michigan-Ann Arbor, said abuses of power are a trade-off to be expected and the benefits outweigh the drawbacks, writing, “Smart systems and the Home of the Future hit at that balance point between individual security and convenience with transparency. There will certainly be some abuses of any such system, but I expect that the convenience to the many will outweigh these concerns about possibilities. Ideally, I’d like to see fail-safes built in, where people regularly use the convenience factors, but are expected to practice ‘unplugging’ from time to time to assure survival in case of catastrophic system failures or intentional hacking.”

Michel J. Menou, visiting professor at the department of information studies at University College London, wrote, “The so-called smart systems are more likely to be developed in order to maximize profits of the providers rather than the comfort and savings of the customers. Their overall benefits in terms of productivity at both ends and energy consumption are still to be demonstrated. They are more likely to be imposed upon the end users till their defects force people to redesign or discard them. In any case the cost and constraints of adapting the existing environment will require far more time for their generalization in the advanced economies.”

An anonymous respondent was highly critical of today’s U.S. take on the free-market economy: “The problem lies not with the technology but the current U.S. version of the ‘free market,’ which increasingly favors an increasingly small handful of well-connected multinational companies. If we extrapolate a future based on the present reality, corporations of the future will only get better at exploiting, manipulating, and lying to both consumers and regulators. Scenario: People are in too much debt; the government is ineffectual; the system is working perfectly!”

Sean Mead, director of solutions architecture, valuation, and analytics for Mead, Mead & Clark, Interbrand, said he expects consumers will not adopt the new home technologies if they perceive that the primary benefit is to the bottom line of corporations. “Smart systems will fail to catch on due to the misalignment between users and beneficiaries,” he predicted. “In all too many cases, the beneficiaries are utilities or large companies, rather than the consumers in whose homes the devices are installed.”

An anonymous respondent used the rollout of metering in France as a negative example, writing, “It won’t be consumer trust that’s an issue; it will be dishonest business practices. GE and others who are positioning for dominance of this market are already figuring out ways to sustain profits, even as electricity consumption is technically reduced by smart systems. They don’t want new competitors to enter the market, and regulators are helping to protect the established firms. So, as in France and other places where smart metering has been deployed, consumers are learning the big utilities are not planning any time soon to altruistically give up the profit margins of the pre-green economy. To think it’s going to be unwilling consumers rather than unwilling capitalists who erect obstacles to the smart-design economy is just naive.”

Nicole Stenger, proprietor of Internet Movie Studio, presented her own 2020 vision, writing: “Home is where the government is. All new homes come pre-installed with invisible webcams, and as half of society is watching the other half, unemployment is resolved. The old name of surveillance becomes ‘observatory of man’s anabasis’ or ‘1 billion blossoms.’ Still, drowning in the mirror of its own triviality, society loses motivation and growth is anemic. Many escape to the mountains in Internet-free reserves, with no Wi-Fi poles or electricity and running water inside houses. But most shrug it off and use the Internet as usual, swapping poems in cyberspace on how to tend to their house plants with a Web-based watering system.”

Some respondents defended corporations and said trust in service providers and in government is not the key sticking point in adoption of smart systems.

Rob Scott, chief technology officer and intelligence liaison at Nokia, explained: “They have failed because 1) they have a significant, detrimental impact on the almost-constant No. 1 criteria for consumers—cost, and 2) they have consistently offered poor to very poor user experiences in their past implementations. As long as proprietary interests are involved in the creation of the underlying components such as switches, outlets, spigots, and so forth, there will never be acceptance. It is the same phenomenon encountered when any industry standard turns out to be either controlled by or reliant upon the intellectual property of one or more standards body members. It is quite possible that closed systems, such as that which would be produced by Apple, will see some success in addressing the second problem listed above. It is only when a fully open implementation that mimics the user experience of a successful closed system (or perhaps beats them to the punch) will the first problem be sufficiently addressed and the public’s acceptance garnered. This will clearly be a top-down (socioeconomic) acceptance trail, as the strength of the economic inhibitor is highly correlated to disposable income.”

An anonymous survey participant took note of privacy and security issues raised by smart systems, writing: “There is an ongoing struggle with RFID and smart-meter technology regarding the enormous amounts of data collected by these devices. IP-enabled devices may provide patterns of behavior—absence or presence in a residence—that could allow a sophisticated thief to access digital records of high electricity use or how frequently a digital TV system is used. Patterns of device usage may provide intelligence on how and when a home is occupied. Personal data is usually linked to these devices along with account and bank information…Harm-based intrusions would rise and the ability to counter such intrusions would be challenged by rapid shifts in cybersecurity paradigms to protect infrastructure.”

Consumers are satisfied with things as they are and it’s hard to retrofit old construction; this will limit adoption of new systems by 2020

The large number of existing homes with old infrastructure and the fact that service providers can optimize systems remotely to individual homes were additional factors expressed as most likely to limit any large-scale adoption of smart systems at the consumer level.

Julia Takahashi, editor and publisher at Diisynology.com, said that as a professional trained in architecture and community planning, she has been hearing about smart buildings and smart cities since the 1970s and she expects a continuation of slow evolution. “Large or complex buildings that require software-controlled systems already have them, and to some extent elements of smart systems have already been adopted on a smaller scale in residential construction,” she pointed out. “We see programmable thermostats, motion-control lighting and plumbing, and home energy auditing. Since new construction only represents a small proportion of our housing stock, we will continue to see incremental adoption. This low level of adoption is due more in part to resident cost/benefit analysis, convenience, and sense of values than because of distrust. The building industry is one of the slowest to adopt new materials and technology. I’m not expecting to see major changes unless the cost of energy gets to a point where it really hurts the pocketbook of most consumers or unless building codes start requiring new technologies.”

Charles Perrottet, partner at the Futures Strategy Group, said it will be a number of years before most connected homes will be “smart.” “The connected household is available and is extremely efficient and eco-friendly,” he said. “It exists, however, in only a very small proportion of the total housing in the United States (or elsewhere). There is a stock and flow issue—most new construction is adopting the new technologies, even at the relatively low end, but it will take several generations to replace enough of the existing inefficient units to have a major impact. This replacement issue has been exacerbated by the extended economic malaise. So consumers have accepted the new technologies. They trust it. They only wish they could afford to buy a new house that embraces it.”

An anonymous respondent said lenders may not want to fund new-home construction with these systems, writing, “Banks will not want to have electronic systems that fail peppered throughout a house that they may end up responsible for selling.” Retrofitting is also a problem for many reasons. Fred Hapgood, a technology author and consultant and moderator of the Nanosystems Interest Group at MIT in the 1990s, said, “Smart systems are very difficult (expensive) to install in a conventionally built house. I see gradual progress over the next twenty-five years, but not much in the next eight-and-a-half.”

Pete Cranston, an Oxford-UK-based consultant on digital media and information and communication technologies for development, said, “2020 is not very far away in terms of the effort involved in smartifying existing housing stock and other infrastructure. This is a 2030 trend.”

Giacomo Mazzone, an executive with the European Broadcasting Union based in Geneva, Switzerland, said controls will be leveraged in a top-down process rather than by individual homeowners. “Power companies can remotely reduce the consumption in homes; ISPs will optimize bandwidth consumption through the network; and so on,” he said. “The individual initiative on smart systems will not become a generalized behaviour and will remain only a privilege of few or some.”

“2020 is too soon,” said Lucretia Walker-Skinner, quality improvement associate with Project Hospitality, a non-profit organization based in Staten Island, New York. “We have a difficult time bringing integration and standardization to reality. Companies frequently develop multiple platforms and then spend years battling it out to see which platform will gain prominence. Development doesn’t take place while everyone waits to see which platform prevails. That in itself makes 2020 too soon. Companies would have to collaborate on an unprecedented level. Also, there would have to be significant incentives for households to adopt this technology, and the incentive would have to be financial. Most people aren’t that interested in the environment and beyond trying to lower their energy bill give little thought to the need for alternative energy sources. I don’t even think trust will be a factor until at least a single platform is utilized and people have financial incentive to do so. Once that’s in place, then the trust factor and privacy concerns will be a factor. Accomplishing this by 2020 will never happen.”

Nobody really wants a smart home; people like their homes to be dumb

Do people suffer somewhat from mass-marketing hypnosis when it comes to the image of the perfect home? There were several who argued that nobody would ever want the pop-culture/Disney/sci-fi sort of future to become reality. “In general, people are very resistant to the idea of home appliances that talk and make decisions. The Home of the Future is a science-fiction fantasy, not a widely held aspiration,” said Lawrence Kestenbaum, founder and owner of PoliticalGraveyard.com

Dave Rogers, managing editor of Yahoo Kids, explained: “The Home of the Future is a consistent myth of American culture, part of the lure of an unattainably rosy future produced by technology. Consider the ebullient scenarios of the 1950s, ones that posited a push-button future, effortless housework, instant communication, and mind-reading appliances. Remember Monsanto’s ‘House of the Future’ at Disneyland, built in the 1950s but still largely a pipe dream for most American homes—and Disney’s utopic ‘Progress City’ at the conclusion of General Electric’s ‘Carousel of Progress’ attraction, laughable today in its unabashed embrace of technology as humanity’s savior. Things just don’t work that way. While technology advances, its initial costs are so high that it retards widespread adoption. Smart-home technology (X-10) has existed for decades and remains unknown except to a few techno-nerds. Further, technology brings its own negatives into the environment, requiring scarce resources (rare earths, for example), polluting, and even dangerous assemblies and so on. I’d like a ‘great big beautiful tomorrow’ just as much as anyone, but it’s just a ‘wish upon a star.’”

Tracy Rolling, product user experience evangelist for Nokia, found the ideal rather laughable. “Bwahahahahah,” she wrote. “Smart homes. Yeah. No. Nobody really wants a smart home. Also, proprietary technology and a lack of organized protocols and formats means that this is not going to take off for a very, very long time. My iPhone won’t want to talk to my GE smart toaster and my Bosch smart refrigerator won’t connect to my generic smart coffee maker. People don’t seem to want this stuff very much. They like for their homes to be dumb. How many people do you know who have bought one of those alarm-clock coffee pots, loved them for a month, and then stopped using the alarm-clock feature all together? Smart homes are like that on a grand scale.”

Tom Worthington, adjunct senior lecturer at the Research School of Computer Science of Australian National University, shared his personal experience. “Ten years ago I bought an apartment which came with fiber optics and data cabling, and so set about building a smart home,” he wrote. “I quickly discovered the pitfalls of this (such as when the computerized hot water system goes mad). The Home of the Future scenarios are based on false assumptions about the way people interact with their houses.”

An anonymous survey participant also shared personal experiences as an example, writing, “I don’t think it will fail due to lack of consumer trust; it’s the fact that people are slow to replace appliances and rewire their homes. (When did you last rewire your house? This one was done in 1920 and we aren’t going to redo it.) It’s possible, but it just seems like it may take 30 to 40 years, and frankly, will people want it? Not because they don’t trust it, but do they need it? Do they care enough to spend the money? Does it really help? I’m really into gadgets and efficiencies and optimization, and I don’t yet see the value of having my fridge ping my phone that we need milk. I’m not that out of touch that I need that and can instead just know from breakfast what’s there. The fridge already cost $3,000 last year. Do I need to spend another $1,000 to get the fridge to message me?”

Walter Dickie, executive vice president and managing partner at C+R Research, shared his view of all of this quite elegantly. “The way people live in their homes is one of the least appreciated, most expressive acts in American culture,” he said. “Except for a small segment of people who identify with a highly engineered, rationalized way of life, living choices are based on other factors entirely. What an efficiency-oriented analysis calls ‘waste’ is the very stuff of life to most, the outward manifestation of who they are and what life is about. It is rank nonsense to believe that a technocratic model of efficiency will dominate the richness—and ‘waste’—of the culture.”