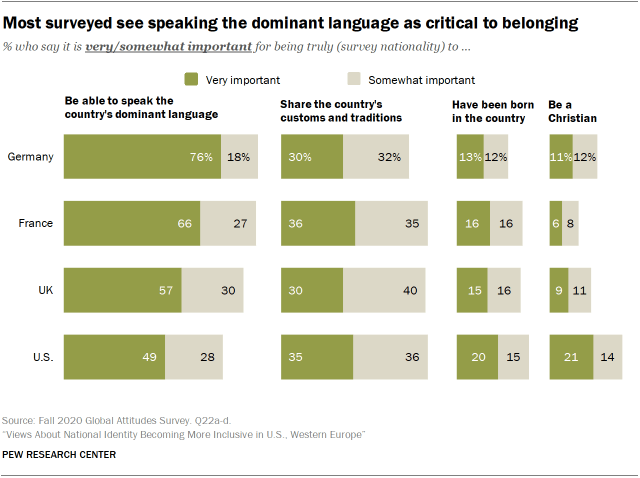

In all four nations surveyed, sizable majorities see speaking their country’s dominant language and sharing its customs and traditions to be at least somewhat important to truly being part of their countries. In Germany, for example, this view is nearly ubiquitous, with 94% saying speaking German is critical to being German, and around three-quarters saying it is very important. Similarly, roughly nine-in-ten in France and the UK think speaking the official language is at least somewhat important, and majorities think it is very important. In the U.S., the share who think speaking English is necessary to being truly American is somewhat lower, though still 77% agree it’s at least somewhat important.

Partaking in national customs is also viewed by most as an integral part of national identity. In France, the U.S. and the UK, about seven-in-ten think sharing their country’s customs and traditions is an important part of being one of them. Among Germans, a smaller majority of roughly six-in-ten say sharing the country’s customs and traditions is at least somewhat important.

By contrast, relatively few in the four countries see birthplace or Christianity as important to belonging in their country. For example, only a quarter think it is important to have been born in Germany in order to be German. Minorities of roughly a third in the UK, France and the U.S. agree. And in most countries, even fewer think identifying as Christian is central to being a part of their country. Only 14% of French think it is important, and about one-in-five Britons and Germans feel the same. Americans are the most likely to think it is important to be Christian, with 35% saying this, including 21% who say it’s very important.

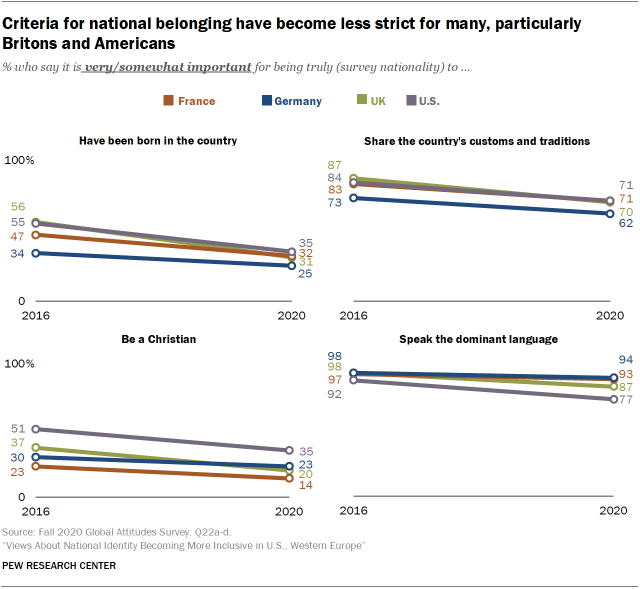

Over the past four years, attitudes about belonging have evolved. In all four countries, people are significantly less likely than they were in 2016 to see being born in their country, sharing national customs and being Christian as important, with declines ranging from about 10 to 25 percentage points. For example, in the U.S. and UK, the share saying that having been born in the country is important to being American or British has fallen 20 and 25 percentage points, respectively.

When it comes to language, those in the U.S. and UK are now less likely to say speaking English is important (down 15 and 11 points in each country, respectively). However, Germans and French are about as likely to consider speaking their countries’ official languages important to being truly German or French today as they were in 2016.

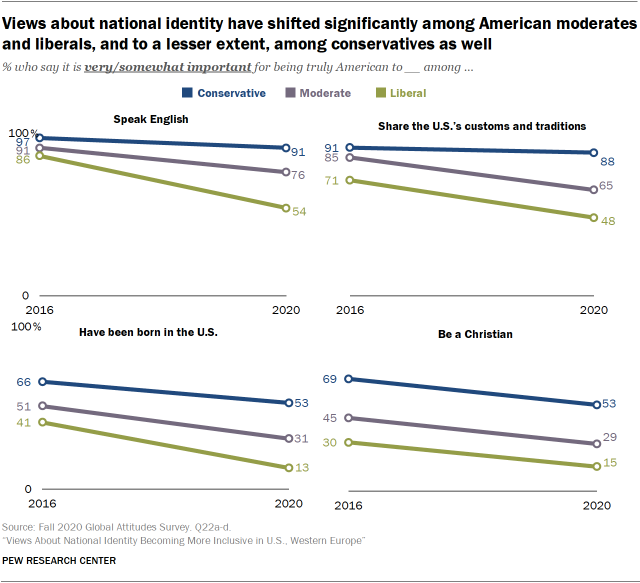

Among the three European publics, these shifts were largely consistent across ideological groups, with similar declines occurring across the spectrum. In the U.S., too, on the importance of being Christian, the shift has been largely consistent across liberals and conservatives, with shifts of around 15 percentage points among each group, respectively. Liberals and conservatives are also both significantly less likely to say it’s important to have been born in the U.S. than they were in 2016, though the shift has been a larger 28 percentage points among liberals compared with 13 points among conservatives.

But, liberal Americans and those in the center have driven much of the change when it comes to attitudes about the importance of speaking English and sharing the country’s customs and traditions. Take, for example, changing attitudes toward sharing American traditions. While the share who thinks this is important fell by 20 points or more among liberals and moderates, there has been no significant change in opinion among conservatives.

Despite these declines, some groups continue to see many of these criteria as more necessary to belong in their country than others. Across all countries, for example, Christians are more likely than non-Christians to see all four criteria as important parts of belonging in their country, with divides being especially sharp on the importance of being Christian. In the U.S., for instance, Christians are four times more likely than non-Christians to think being Christian is an important part of being American (48% vs. 12%).

Additionally, across all four countries surveyed, those who think their country will be better off sticking to traditions are generally more likely than those who prioritize being open to changes to think all four qualities are important to being part of their country. For instance, French who support a more traditional direction for their country are about twice as likely to think people must be Christian to be truly French compared with those who think their country should evolve.

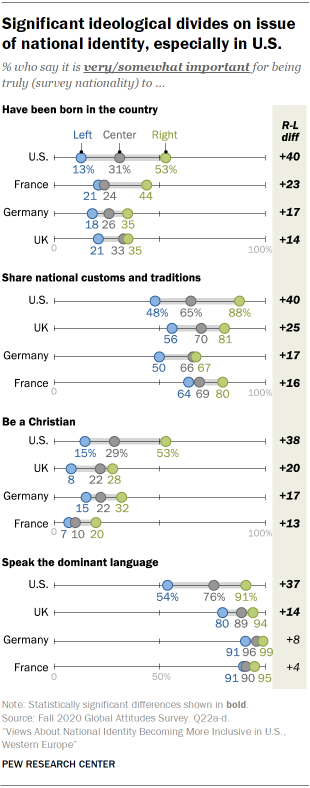

Those on the ideological right, too, are more likely than those on the left to say most of these factors are an important part of fitting in. The only exception is on speaking the dominant language. Those on the left and right in Germany and France are equally likely to think speaking the language is a critical piece of belonging.

“You’ve got a lot of people coming into the country now who don’t want to be British, they don’t want to integrate. They don’t want to mix … I wouldn’t go to Spain and start ranting on about being English.”

–Man, 41, Birmingham, Left Leaver

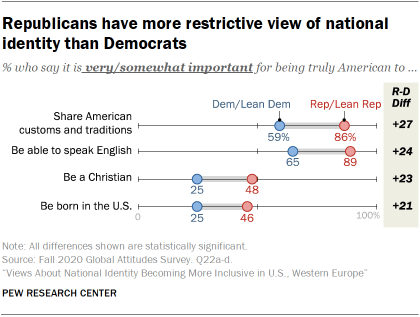

The ideological divides are deepest in the U.S. Those on the right are around 40 percentage points more likely than those on the left to say every facet of belonging asked about is important.

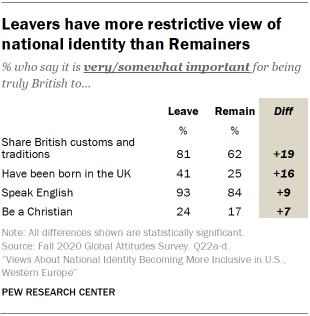

These divides are also stark between Britons with different attitudes toward Brexit, with Leavers being 19 points more likely than Remainers to say sharing British customs is important. Leavers and Remainers also diverge over the importance of being born in the UK, speaking English and being Christian.

In the UK and U.S., focus group participants with different ideological and partisan identities clashed over what it takes to be British and American

Focus groups highlighted the way ideology and views about Brexit intertwined to inform opinions about what qualifies someone as British. When asked what being British means and whether people from other cultures can be British, focus groups composed of Leavers, and particularly Leavers on the right, frequently brought up speaking English, adhering to British values and, to a lesser extent, being Christian, as necessary. Some Leavers on the right talked about these issues in very explicit terms, viewing the presence of people who do not meet their criteria of Britishness – e.g., by not speaking English in public or by following customs of their countries of origin, including wearing traditional dress – as a personal affront and threat to the integrity of Britain. One right-leaning woman who voted to leave the EU noted that hearing people speak other languages in public was “awful” and created a “hostile environment” for her. Others complained about immigrants following customs of their countries of origin (e.g., eating with their hands) instead of adapting British traditions, further suggesting that their presence has burdened social services and that special accommodations were made for them.

Right-leaning Remainers and left-leaning Leavers echoed some of these concerns about immigrants assimilating. They often saw the presence of people from other cultures in the UK as positive, on the condition that those individuals follow British traditions – described in focus groups as queuing or having a “stiff upper lip,” among other traits. Remainers on the ideological left were unlikely to mention any of these criteria for Britishness and were clear that not only can people from other cultures be British, but that multiculturalism and cultural exchange added value to British society.

Differences of opinion emerged along partisan lines in the U.S. focus groups. When asked what it means to be American and whether people from other cultures can be American, groups consisting of Republicans were the only ones to mention Christianity as a part of being American and to focus on the importance of speaking English and adopting American values, particularly following laws. Like in the UK, many said a failure to learn English and adhere to American customs puts a strain on resources and threatens the country. One example cited by a Republican in Seattle was about the cost school districts had to bear to hire interpreters, and a feeling that immigrants are less likely to learn English today compared with the past, because of these accommodations.

When these questions were posed to groups comprising Democrats, responses often focused on the diversity of the U.S. as a positive thing. And like left-leaning Remainers in the UK, Democrats tended to agree that people from other cultures could be American without any caveats, though some agreed with Republicans that certain standards like following U.S. customs must be met. However, they rarely framed a failure to meet these standards as a burden for the U.S. or a threat to other Americans. And those that did not see any of these criteria for being American largely agreed that diversity and immigration added value to their country.

Political affiliation also plays a role, and like the ideological divides, the differences between partisans is especially stark in the U.S., where Republicans and those who lean toward the Republican party are significantly more likely than their Democratic counterparts to see all four qualities as crucial to American identity.

“[What it takes to be one of us is to] assimilate into the culture and understand the history of the country, the values of the country, what entrepreneurship is, what freedom of speech is, the right to bear arms, to understand why this country is the greatest country in the world … The key to keeping it great is for those individuals to assimilate into the culture.”

–Man, 58, Seattle, Republican

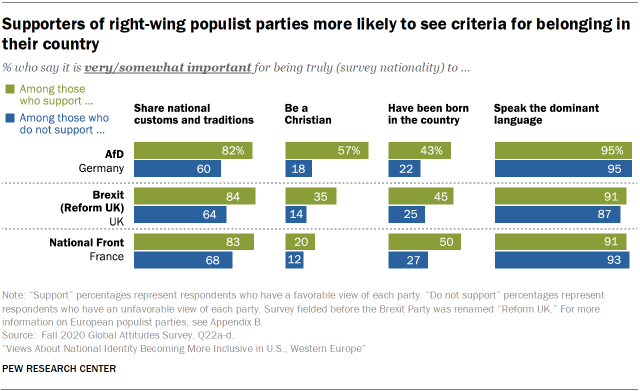

Across the Atlantic, those with positive views of right-wing populist parties are more likely to view birthplace, adherence to national customs and being Christian as key to belonging in their countries. For instance, Germans who support Alternative for Germany (AfD) are roughly three times as likely as those who do not to think being Christian is a critical part of being German. When it comes to language, though, supporters of populist parties and nonsupporters largely agree that it’s important to speak the national language.

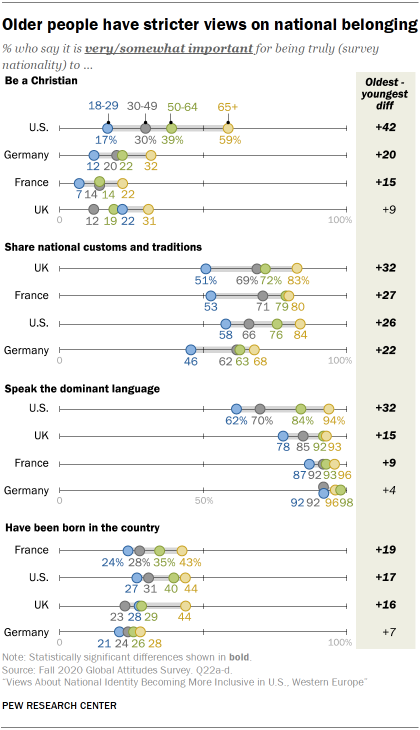

Age is also related to opinion: Older people have stricter requirements about what it takes to belong in their country than younger ones. In all four countries surveyed, those 65 and older are more likely than adults under 30 to say following national customs is necessary. Similar divides are seen in France, the UK and the U.S. on the importance of speaking the dominant language and being born in the country, though German views on these criteria is consistent across age groups. Outside of the UK, older adults are more likely than younger ones to see being Christian as important for national identity.

In addition, across all four nations, those with less education are more likely than those with more education to think being born in their country, following local customs and being Christian were important. However, only in the U.S. is education related to opinions about speaking the dominant language.2