Updated May 27, 2014

The original version of this report included public opinion data on the connection between religion and morality in China that has since been found to have been in error. Specifically, the particular survey item that asked whether one needed to believe in a higher power or God to be a moral person was mistranslated on the China questionnaire, rendering the results incomparable to the remaining countries. For this reason, the data from China has been removed from the current version of the report, re-released in May 2014.

For further information, please contact info@pewresearch.org.

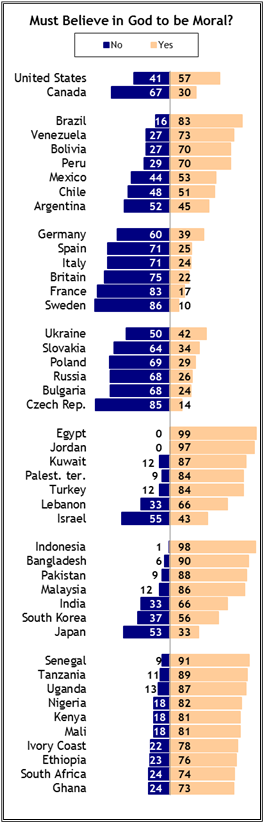

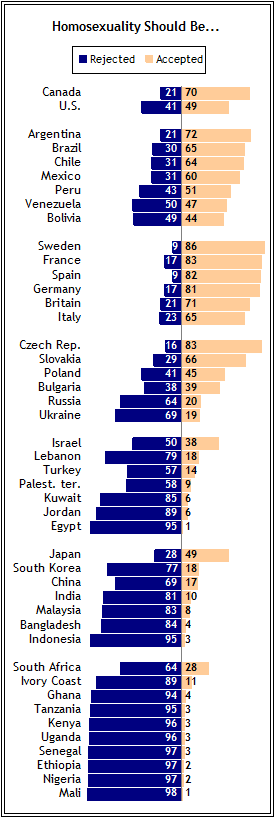

Questions about religion and homosexuality reveal some of the sharpest divides on the 2007 Pew survey. Throughout much of Africa, Asia and the Middle East large majorities feel that faith in God is a necessary foundation for morality and good values, and similar majorities believe society should reject homosexuality.

However, in the relatively wealthy and secular nations of Western Europe, large majorities suggest that morality is possible without faith and believe homosexuality should be accepted. The belief that moral values do not require faith is also common in formerly communist Eastern Europe, but attitudes in the region toward homosexuality are more mixed.

In the Americas, including the United States, views on these issues are also mixed. And in many countries, there is a significant age gap, with younger people significantly more likely to reject the notion that morality requires a belief in God, and considerably more likely to be tolerant of homosexuality.

A global consensus does emerge, however, regarding the separation of religion and the state. In nearly every country surveyed, majorities agree that religion is a matter of personal faith that should be unconnected to government policies.

Finally, as the survey reveals, many in the Muslim world see a struggle taking place between fundamentalists and those who want to modernize their countries.

Is Faith Necessary for Morality?

Throughout most of Africa, Asia, and the Middle East, there is widespread agreement that faith in God is a prerequisite for morality. For example, in all 10 African countries included in the study, at least seven-in-ten respondents agree with the statement “It is necessary to believe in God in order to be moral and have good values.” In Egypt, no one in the sample of 1,000 people disagrees. Out of the 1,000 Jordanians interviewed, only one person suggests it is possible to not believe in God and still be a moral person.

In the four predominantly Muslim Asian countries – Indonesia, Bangladesh, Pakistan and Malaysia – huge majorities also believe morality requires faith in God. Elsewhere in Asia, however, opinions are a bit more mixed. A majority in Japan, as well as substantial minorities of Indians and South Koreans, reject the notion that believing in God is required for morality.

In Arab countries there is a strong consensus that faith is necessary, although in Lebanon there are substantial differences among the country’s three major religious communities – Shia Muslims (81% agree), Christians (65%), and Sunni Muslims (54%). In neighboring Israel, a slim majority (55%) think faith in God is not necessary for moral values.

In Europe, the consensus view is just the opposite: throughout Western and Eastern Europe, majorities say faith in God is not a precondition for morality. This is true across Europe, regardless of whether a country’s primary religious tradition is Protestant, Catholic or Eastern Orthodox. And it is true regardless of which side of the Iron Curtain a country was on. Still, even within Europe there is some variability – Swedes, Czechs, and the French emerge as the most likely to reject the necessity of religion, while Ukrainians, Germans, and Slovaks are the least likely.

Meanwhile, in the Americas there are considerable differences among countries. While Brazilians, Venezuelans, Bolivians, and Peruvians tend to believe faith is a necessary foundation for moral values, Mexicans, Chileans, and Argentines are more divided on this issue. Only 30% of Canadians suggest morality is impossible without faith, compared to nearly six-in-ten Americans (57%).

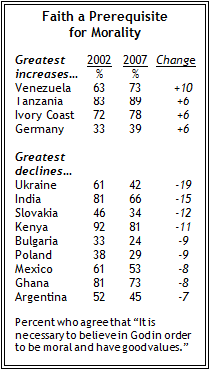

Over the last five years, there has been no clear overall pattern of change on this question. The percentage of people who think believing in God is necessary has increased in nine countries, stayed about the same in ten, and declined in 13. While there may be no clear global trend, however, there have been important shifts in a few countries.

Venezuelans are significantly more likely now than in 2002 to say a person must be religious to be moral. Tanzanians, Ivoirians and Germans are also more likely to hold this view.

However, several countries show a steep decline in the number of people who feel morality requires a belief in a higher power. Decreases are particularly common in Eastern Europe – Ukrainians, Slovakians, Bulgarians and Poles have grown less inclined to tie religion and morality. Indians and Kenyans are also now less likely to say faith is necessary for a moral life.

Sharp Differences Over Homosexuality

Many of the patterns regarding views about religion and morality also characterize opinions about homosexuality. In Western Europe, clear majorities say homosexuality is a way of life that should be accepted by society. Among Eastern Europeans, however, opinions are more diverse: Czechs and Slovaks strongly believe homosexuality should be accepted, while Poles and Bulgarians are closely divided on this issue, and Russians and Ukrainians tend to oppose acceptance.

Opinions are also divided in the Americas. Seven-in-ten Canadians believe society should accept homosexuality, compared to roughly half of Americans (49%). In Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and Mexico tolerant attitudes toward homosexuality prevail, while in Peru, Venezuela, and Bolivia views are more divided.

In Africa, Asia and the Middle East, attitudes toward homosexuals are overwhelmingly negative. In eight of 10 African publics, less than 5% feel society should accept homosexuality. Of the 24 nations from Africa, Asia, and the Middle East where this question was asked, Japan is the only country in which a plurality (49%) believe it should be accepted.

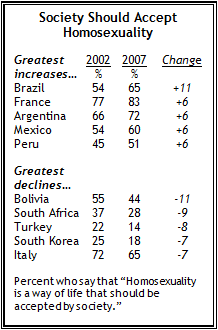

Since 2002, several Latin American countries – Brazil, Argentina, Mexico and Peru – have developed more tolerant attitudes toward homosexuals. In Bolivia, however, the trend is in the opposite direction – in 2002, 55% said homosexuality should be accepted by society, compared to only 44% today.

Other publics have become less tolerant on this issue as well, especially South Africa, Turkey, South Korea and Italy. Overall, among the 32 countries where trends are available, 12 have become less tolerant, six more tolerant, and in 14 countries there has been no significant change.

An Age Gap on Religion, Homosexuality

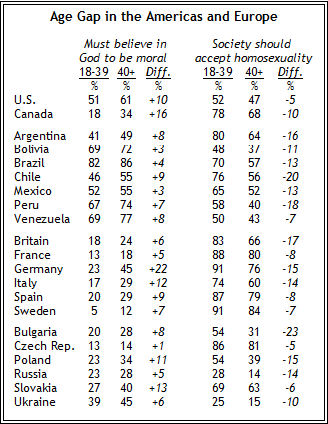

Throughout North and South America and Europe, there is a consistent age gap on views about religion and homosexuality. In each country from these regions, people under age 40 are less likely than those age 40 and over to think a belief in God is necessary for morality, and more likely to believe that society should accept homosexuality.

In some cases, the gap between young and old is quite large. For example, nearly half (45%) of Germans age 40 or older think a person must believe in God to be moral, compared to only 23% of those under 40. And while 54% of younger Bulgarians think homosexuality should be accepted, only 31% of older Bulgarians agree.

In the United States, there is a slight age gap on the issue of homosexuality and a larger gap on the relationship between religion and morality. As with many social issues, there are also considerable differences along party lines – Republicans are more likely to say that a belief in God is required for good values (64%) and less likely to say homosexuality should be accepted (33%) than are Democrats (59% must believe in God to be moral, 56% society should accept homosexuality) or independents (48% must believe in God, 57% should accept homosexuality).

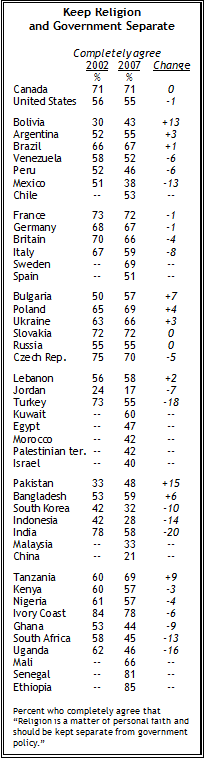

Most Want Religion and Government Separate

There is a consensus across regions that religion and governing do not mix. In 46 of 47 countries, majorities agree with the statement “Religion is a matter of personal faith and should be kept separate from government policy.”

However, while support for keeping religion and state policies separate generally remains high, the intensity of that support has declined. The percentage of people who completely agree with this principle has dropped in 17 of 33 nations where there are trends from 2002, while remaining basically stable in eight countries and increasing in another eight.

Support for keeping politics and religion separate tends to be somewhat lower in the Middle East. In Jordan, only 17% completely agree with this principle, and Jordan is the only country in the survey where a majority (53%) disagree. In neighboring Egypt, 49% disagree, and in the Palestinian territories, where the Islamist group Hamas controls the Gaza Strip, 42% disagree.

The trend on this question is moving in different directions in two major Muslim countries that are key allies of the United States: Turkey and Pakistan. Support for separation has declined considerably in traditionally secular Turkey, which recently handed a moderate Islamist party, the Justice and Development Party (known by its Turkish acronym AKP), its second straight national election victory. On the other hand, support for keeping mosque and state separate has increased in Pakistan, which has experienced considerable political tensions in recent months, including armed conflict between government forces and extremist groups.

Elsewhere in Asia, the percentage of people who completely agree that religion should be disconnected from policy is relatively small. Fewer than one-in-three Chinese, Indonesians, South Koreans and Malaysians completely agree with this perspective. Worries about mixing religion and public policy have declined steeply in India, where the Hindu nationalist party, the Bharatiya Janata Party or BJP, was defeated in the 2004 national elections.

Several African publics have become less supportive of separation, especially Uganda, South Africa and Ghana. Elsewhere on the continent, however, support remains quite high. Indeed, the three countries on the survey with the largest percentages endorsing separation are Ethiopia (85%), Senegal (81%) and Ivory Coast (78%).

Throughout Europe, Canada, and the United States, majorities completely back the separation of religion and politics, although these majorities are notably slim in Italy (59%), Bulgaria (57%), Russia (55%), the U.S. (55%), and Spain (51%).

Modernizers and Fundamentalists in the Muslim World

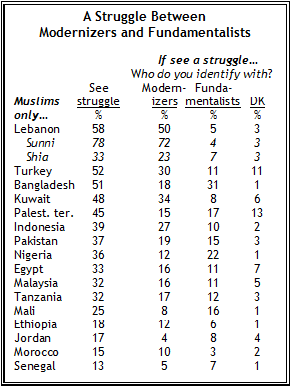

In nations with large Muslim populations, a significant number of people feel a struggle is taking place between Islamic fundamentalists and groups that want to modernize their country. In 11 of the 16 nations where this question was asked, at least three-in-ten Muslims say there is a conflict between fundamentalists and modernizers. In 10 of 16 countries, those who believe there is a struggle tend to identify with the modernizers, while in six countries a plurality favor the fundamentalists.

The perception that a struggle is taking place is particularly common in Lebanon, a country rife with political and sectarian conflict. However, the country’s two main Muslim communities see this issue very differently. Lebanese Sunni strongly believe there is struggle and tend to side with modernizing groups, while most Shia do not believe there is a struggle.

Just over half (52%) of Turks see a conflict in their country, where there has been considerable tension in recent months between followers of the ruling AKP party and the country’s traditional secular elites over issues involving religion and politics, such as the wearing of veils by Muslim women.

African Muslims are somewhat less likely to perceive a struggle, especially in Senegal, Ethiopia and Mali. Perceptions of a struggle are somewhat more common in Nigeria and Tanzania, where roughly one-in-three Muslims say there is a conflict.