About a million people (1.1 million) who sought asylum in Europe in 2015 and 2016 still did not know by Dec. 31, 2016, whether they would be allowed to stay, according to new Pew Research Center estimates based on government data. Those in limbo make up about half (52%) of the 2.2 million1 people who applied for asylum during one of the largest refugee waves ever to arrive to the European Union, Norway and Switzerland.2

Some 1.3 million first-time asylum applications alone were filed in EU countries, Norway and Switzerland in 2015 and an additional 1.2 million were filed in 2016. Together, these two years account for 20% of all asylum applications received by Europe since the mid-1980s, making this wave of asylum seekers the biggest the continent has seen since World War II. Top countries of citizenship for asylum seekers during the record surge included Syria, Afghanistan and Iraq, countries whose ongoing conflict has contributed to the sudden increase in displaced people worldwide. These three countries accounted for more than half (53%) of all 2015-16 applicants.

Most asylum seekers during the surge entered Europe through Greece or Italy. Migration along the Eastern Mediterranean route between Turkey and Greece stalled after a deal between the EU and Turkey was implemented in March 2016 to contain the flow. Thousands more migrants, however, crossed the Central Mediterranean from North Africa to Italy in a steady flow through most of 2016.

Many asylum seekers did not stay in Mediterranean countries. Instead, they traveled north. Germany received roughly half (45%) of Europe’s asylum seekers during 2015 and 2016, with hundreds of thousands also applying in Hungary and Sweden. For some European countries, the sudden movement of so many asylum seekers changed the demographics of those countries noticeably: Immigrant shares of total populations increased by more than 1 percentage point in countries like Sweden and Austria between 2015 and 2016.

Among Europe’s asylum seekers from the 2015-16 surge who were waiting on decisions as of the end of 2016, an estimated two-thirds (or about 760,000) had not had a decision made on their case. Another third (about 385,000) were appealing the first decision after being rejected.

Meanwhile, an estimated 885,000 asylum seekers applying between 2015 and 2016 had their applications approved by the end of 2016, meaning they may stay in Europe, at least temporarily.3 A remaining 75,000 applicants are estimated to have been returned to their home countries or another non-EU country during this time period. The current location of about 100,000 applicants whose applications were rejected is unknown. It is possible that they stayed within Europe illegally, left Europe or applied for some other immigrant status.

These are some of the key findings from Pew Research Center estimates based on data from Eurostat, the European Union’s statistical agency. For details about the source data and the method used to estimate the status of asylum seekers, see the methodology.

Applying for asylum in Europe

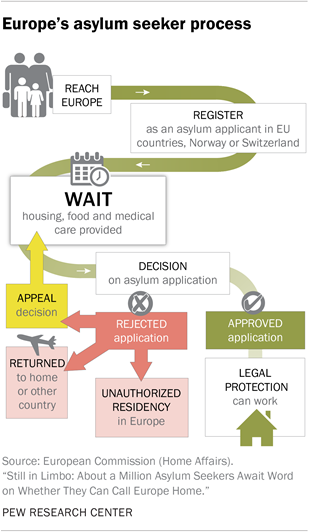

All refugees in Europe, whether minors or adults, are required to individually apply for asylum with the authorities of the country where they first arrived. The wait for an application to be adjudicated can vary considerably from country to country, even though European Union countries, Norway and Switzerland have agreed to common principles in dealing with asylum seekers.

Some of the shorter wait times have been for Syrians in Germany, where the average adjudication period for Syrian applicants has been about three months during 2015 and 2016. By contrast, the average wait time for asylum seekers in Norway has been more than a year. These widely ranging timelines are dependent on a number of factors, including processing capacity, origin of an asylum seeker, and political pressure on authorities to either accelerate or slow the processing of asylum applications.

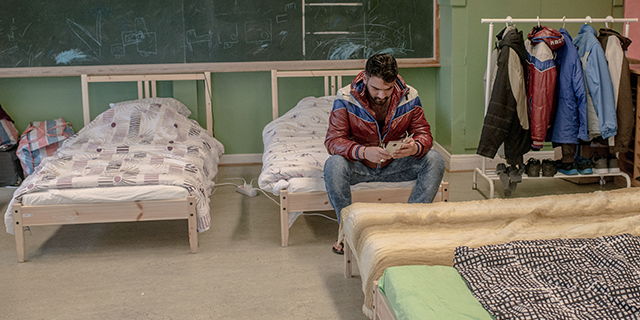

While their applications are processed, many asylum seekers await decisions in government-run facilities such as repurposed schools, hotels or airports, where they are provided food and medical care. Some asylum seekers, especially those from Syria, have been fast-tracked and have waited just a few months before receiving decisions. Others have lived in refugee quarters for months or longer, awaiting final verdicts on whether they will be able to stay. In most European countries, asylum seekers are initially prohibited from working, though they sometimes have access to the labor market if the application process is delayed beyond several months, depending on the European country.

If an asylum seeker’s application is approved, she or he receives residency status for a certain number of years, depending on the situation and the country of application.4 The asylum grantee is also permitted to obtain legal employment. If an application is rejected, an individual can file an appeal and wait, again, for a new decision. Appeals can add several months, if not more, to an asylum seeker’s overall wait time. Alternately, applicants who are rejected may be returned to their home countries or sent to a non-EU country. Some also remain in Europe as unauthorized immigrants.

Compared with Europe, the number of people claiming asylum in the United States has numbered only in the thousands in recent years, not the millions seen in Europe. Instead, many seeking protection in the U.S. are resettled as refugees through the State Department’s Refugee Resettlement Program. These refugee applicants are processed outside the U.S.

Estimating the status of Europe’s refugee surge

Eurostat, Europe’s statistical agency, regularly releases figures on the number of asylum seeker decisions in European Union countries, Norway and Switzerland. But, these numbers do not indicate when applications were filed, whether it was a few weeks before or several years earlier. Consequently, the status of the refugee surge that peaked between 2015 and 2016 is unknown to the public. For the first time, the Pew Research Center estimated the status of this refugee flow based on publicly available data from Eurostat and other sources as of the end of 2016. Full details on how the status of Europe’s refugee surge was estimated can be found in the methodology.

Some 2.2 million applications are estimated to have been filed in 2015 and 2016, excluding withdrawn applications. Excluding withdrawn applications improves the accuracy of asylum-seeker estimates by reducing the chance of double-counting individuals who may apply in multiple countries or returned back home on their own before seeing their applications processed.

The number of approved and rejected applications was estimated using the number of decisions among first-time applicants in each quarter of 2015 and 2016, as provided by Eurostat. Some countries take longer than others to reach a decision on applications. Average wait times in each country were collected from reports of NGOs on the ground. The number of application decisions (approvals or rejections) used in the estimates is based on how long applicants waited on average in each European country to see their application adjudicated. Applicants with an uncertain future include those waiting to have their first-time application decided, as well as those appealing an initial rejection. The estimated number of appeals is based on annual appeal rates from previous years, taking into account the applicant’s nationality and country of application.

The remainder of Europe’s refugee surge has returned to their home countries after receiving an order to do so, either voluntarily or by force. For others, their location is unknown following a rejected refugee claim. These latter groups of asylum seekers are estimated using 2016 data on annual returns from EU countries, Norway and Switzerland.

Majorities of asylum seekers from many countries don’t know whether they can stay in Europe

About half (52%) of all asylum seekers who had applied in European Union countries, Norway and Switzerland during 2015 and 2016 still were waiting for word on their applications or appeals at the end of 2016. A smaller, yet substantial, share (40%) had been approved to stay. The remaining applicants (about 8%) have either returned to their home or another non-EU country or their location is unknown. The status of Europe’s asylum seekers can be examined in two ways: by their nationality and by their countries of application.

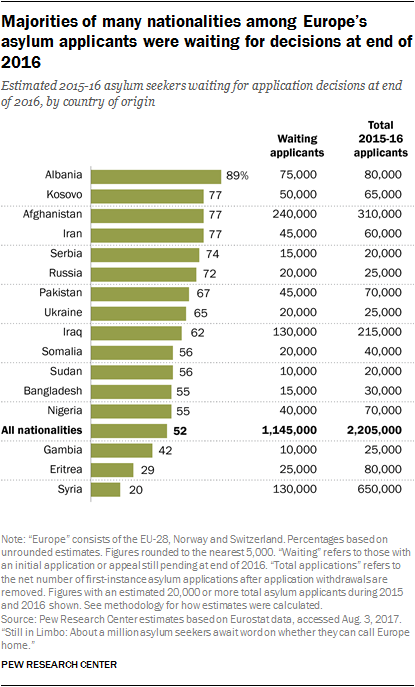

For asylum seekers from certain countries, the share that is waiting is much higher than the share that has been approved for protection in Europe, according to the new estimates. For example, an estimated 89% of Albanian applicants between 2015 and 2016 were waiting to know their status in Europe at the end of 2016.

Also, about 77% of Afghan asylum applicants were waiting for first-time or final decisions on appeals. This means that there were more than three times as many applicants from Afghanistan waiting (240,000) as approved ones (70,000) at the end of 2016. A large share (77%) of Iranian applicants and more than half of those from Iraq (62%) were also still waiting on first or final decisions at 2016’s end.

At the same time, about three-fourths of asylum seekers from top European nationalities during the surge, such as those from Kosovo (77%), Serbia (74%) and Russia (72%), were waiting on word on first-time or appeal decisions as of the end of 2016.5

Between half and two-thirds of top applicants from South Asia such as Pakistan (67%) and Bangladesh (55%) were waiting on application decisions as of the end of 2016. Meanwhile, more than half of applicants from several leading African countries of the surge, such as Somalia (56%), Sudan (56%) and Nigeria (55%), were waiting on application decisions at the end of 2016.

Not all nationalities of asylum seekers follow the same pattern of more waiting than approved applicants. For example, the future for most Syrian applicants applying for asylum in 2015 and 2016 is largely certain in Europe, at least for the next several years. Only an estimated 130,000 of the 650,000 applications received by Syrians (20%) had not been decided by the end of 2016, either for the first time or because of an appeal.

Some European countries established fast-track processing for several nationality groups, including Syrian asylum applicants, the top country of origin for asylum seekers during the 2015-16 surge. In Germany, for example, Syrians often received first-time asylum application decisions within three months of their applications during 2015 and 2016, with many being approved without an appeal. In Belgium, nongovernmental organizations report that decision wait times averaged around one month for Syrian asylum seekers.

Similarly, well fewer than half of 2015-16 applicants from Gambia (42%) and Eritrea (29%) were still awaiting decisions on their applications at the end of 2016, according to Pew Research Center estimates. In the case of Gambians, an estimated 10,000 out of 25,000 applicants applying in 2015 and 2016 were still waiting to hear results for their asylum applications or appeal by the end of 2016. For Eritreans, about 25,000 of the 80,000 applicants applying in these years did not know their status. Asylum applicants from Gambia are often granted refugee status because of ongoing political strife, while Eritreans are largely escaping forced military conscription.

More than half of asylum applicants in several European countries are waiting for decisions

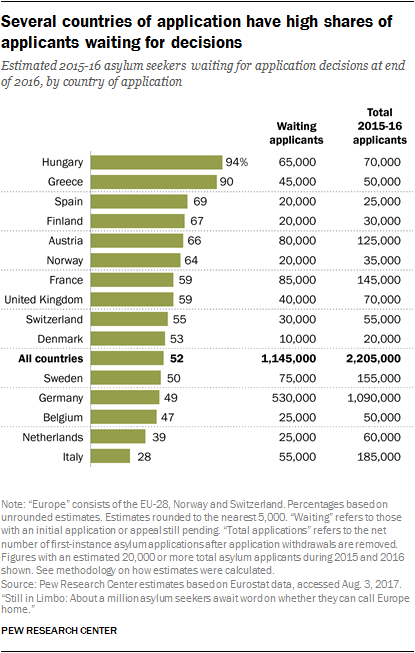

The status of Europe’s asylum seekers is largely dependent on where applications are submitted. Wait times and application decisions made by countries can vary greatly.

Several European countries on the front lines of the refugee surge in 2015-16 had high shares of asylum applicants waiting for decisions on their applications as of the end of 2016, according to Pew Research Center estimates. For example, it is estimated that about nine-in-ten applicants in Hungary (94%)6 and Greece (90%) were still waiting for decisions as of Dec. 31, 2016.

According to the new estimates, about two-thirds of applicants in Austria (66%) and 59% of those in France – other countries that received large numbers of asylum seekers in 2015-16 – were waiting for application decisions.

Although Germany received close to half (45%) of Europe’s asylum applicants in 2015 and 2016, it appears to have been more efficient than many other countries in processing asylum applications. As of Dec. 31, 2016, about 530,000 asylum applicants – or 49% of those arriving in 2015 and 2016 – are estimated to be waiting for decisions, a slightly lower share than the 52% Europe-wide.

Sweden, another top receiving country of asylum seekers, had a similar share (50%) to Germany for applicants awaiting decisions at the end of 2016, or about 75,000 applicants.7 About the same number (75,000) of applications had been approved by Swedish authorities as of Dec. 31, 2016.

Few rejected asylum seekers in Europe have been returned to home countries

Some 75,000 rejected asylum seekers, about 3% of all applicants from Europe’s 2015 and 2016 surge, had been returned to their home countries or sent to a non-EU country by the end of 2016, according to Pew Research Center estimates (see methodology for details). Germany, the country receiving the most asylum seekers during this period, also returned more asylum applicants than other countries.8

Note: This section has been updated to clarify that it applies to rejected asylum seekers only.

Location of a small number of rejected asylum seekers is unknown

The current location of an estimated 100,000 rejected asylum seekers who applied for asylum in 2015 or 2016 is unknown. These applicants could be living in or outside European Union countries, Norway and Switzerland. This amounts to less than 5% of the total number of asylum seekers who applied during 2015 and 2016, according to Pew Research Center estimates.

These asylum seekers had their applications rejected and are believed to have been neither in the appeal process nor returned to their home countries by the end of 2016. If these individuals were still in Europe at the end of 2016, they were likely unauthorized immigrants and subject to deportation if found.

The term “Europe” is used in this report as a shorthand for the 28 nation-states that form the European Union (EU) as well as Norway and Switzerland, for a total of 30 countries. At the time of the production of this report, the UK was still part of the European Union even though the country triggered Article 50 on March 29, 2017 to begin its withdrawal from the EU. These countries are bound by the Dublin Regulation: Asylum seekers must apply for asylum in the first EU country they enter, and if they do not, they can be returned to the first country they enter for the processing of their applications. Most EU countries, Norway and Switzerland are also part of the Schengen agreement, which permits people to cross between countries without border checks.

The terms “asylum seekers,” and “asylum applicants” are used interchangeably throughout this report and refer to individuals who have applied for asylum in a European country after reaching Europe. All family members, whether male or female, children or adults, file individual applications for asylum. Seeking asylum does not mean applicants will necessarily be permitted to stay in Europe. However, if an asylum application is approved, the asylum seeker is granted refugee status or some other humanitarian (sometimes temporary) status, given the right to remain in Europe and work. Data in this report note both the country of citizenship (nationality) of applicants as well as the country where the asylum application was filed (country of application)

“Refugees” denotes both the group of people fleeing conflict to a nearby country and those whose asylum application in Europe has been approved. For the latter group, the term “refugee” denotes a legal status after an asylum application is approved.