An unprecedented amount of public attention focused on Muslim Americans in the wake of the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001. The U.S. Muslim population has grown in the two decades since, but it is still the case that many Americans know little about Islam or Muslims, and views toward Muslims have become increasingly polarized along political lines.

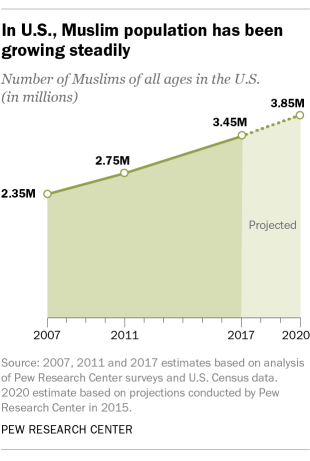

There were about 2.35 million Muslim adults and children living in the United States in 2007 – accounting for 0.8% of the U.S. population – when Pew Research Center began measuring this group’s size, demographic characteristics and views. Since then, growth has been driven primarily by two factors: the continued flow of Muslim immigrants into the U.S., and Muslims’ tendency to have more children than Americans of other faiths.

In 2015, the Center projected that Muslims could number 3.85 million in the U.S. by 2020 – roughly 1.1% of the total population. However, Muslim population growth from immigration may have slowed recently due to changes in federal immigration policy.

The number of Muslim houses of worship in the U.S. also has increased over the last 20 years. A study conducted in 2000 by the Cooperative Congregational Studies Partnership identified 1,209 mosques in the U.S. that year. Their follow-up study in 2011 found that the number of mosques had grown to 2,106, and the 2020 version found 2,769 mosques – more than double the number from two decades earlier.

This analysis examines how the experiences of Muslim Americans, and attitudes toward Muslims and Islam among Americans overall, have changed in the two decades since the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001. It is based primarily on Pew Research Center surveys conducted by phone and online during that timespan. Sample sizes, field dates and methodological information for each survey are accessible through the links in this analysis.

Alongside their population growth, Muslims have gained a larger presence in the public sphere. For example, in 2007, the 110th Congress included the first Muslim member, Rep. Keith Ellison, D-Minn. Later in that term, Congress seated a second Muslim representative, Rep. Andre Carson, D-Ind. The current 117th Congress has two more Muslims alongside Carson, the first Muslim women to hold such office: Reps. Ilhan Omar, D-Minn., and Rashida Tlaib, D-Mich., first elected in 2018.

As their numbers have increased, Muslims have also reported encountering more discrimination. In 2017, during the first few months of the Trump administration, about half of Muslim American adults (48%) said they had personally experienced some form of discrimination because of their religion in the previous year. This included a range of experiences, from people acting suspicious of them to being physically threatened or attacked. In 2011, by comparison, 43% of Muslim adults said they had at least one of these experiences, and 40% said this in 2007.

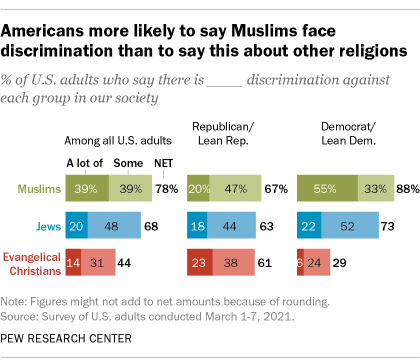

In a March 2021 survey, U.S. adults were asked how much discrimination they think a number of religious groups face in society. Americans were more likely to say they believe Muslims face “a lot” of discrimination than to say the same about the other religious groups included in the survey, including Jews and evangelical Christians. A similar pattern appeared in previous surveys going back to 2009, when Americans were more likely to say that there was a lot of discrimination against Muslims than to say the same about Jews, evangelical Christians, Mormons or atheists.

A series of Pew Research Center surveys conducted in 2014, 2017, and 2019 separately asked Americans to rate religious groups on a scale ranging from 0 to 100, with 0 representing the coldest, most negative possible view and 100 representing the warmest, most positive view. In these surveys, Muslims were consistently ranked among the coolest, along with atheists.

Over the last 20 years, the American public has been divided on whether Islam is more likely than other religions to encourage violence, and a notable partisan divide on this question has emerged. When the Center first asked this question on a telephone survey in 2002, Republicans and Republican-leaning independents were only moderately more likely than Democrats and Democratic leaners to say that Islam encourages violence more than other religions – and this was a minority viewpoint in both partisan groups. Within a few years, however, Republicans began to grow more likely to believe that Islam encourages violence. Democrats, in contrast, have become more likely to say Islam does not encourage violence. Now, Republicans are far more likely than Democrats to say they believe Islam encourages violence more than other religions.

Though many Americans have negative views toward Muslims and Islam, 53% say they don’t personally know anyone who is Muslim, and a similar share (52%) say they know “not much” or “nothing at all” about Islam. Americans who are not Muslim and who personally know someone who is Muslim are more likely to have a positive view of Muslims, and they are less likely to believe that Islam encourages violence more than other religions.