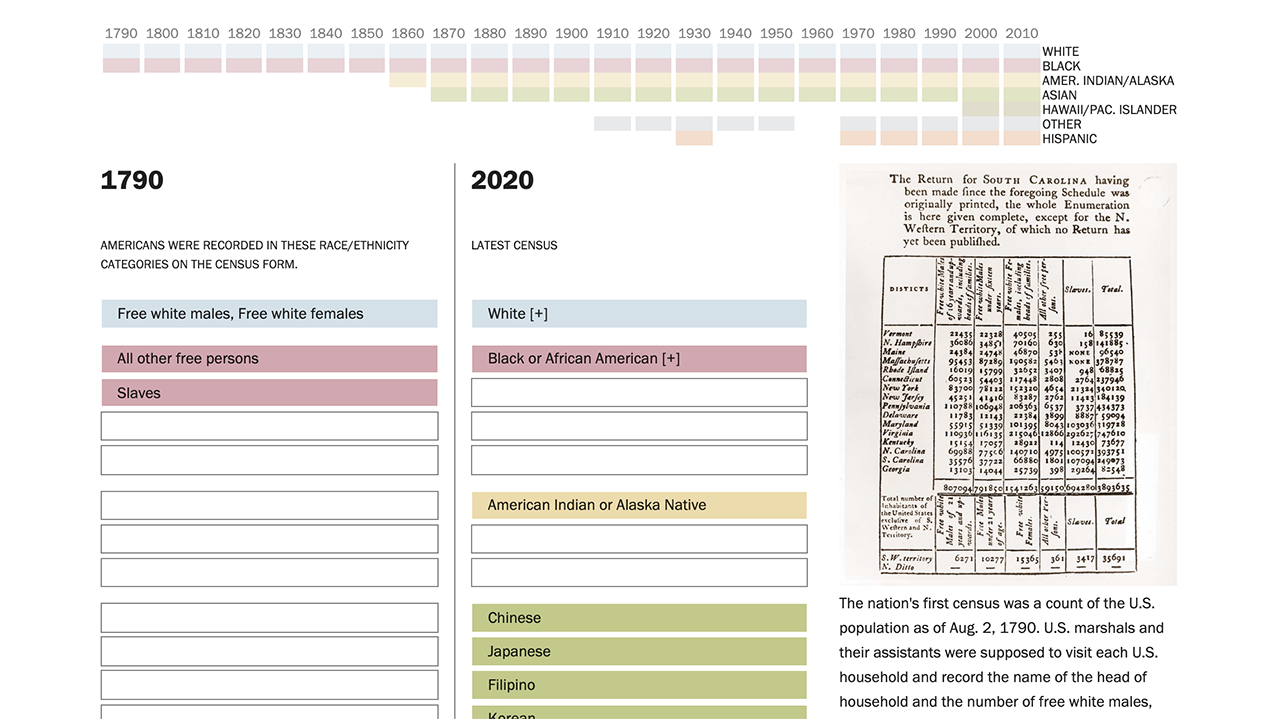

The varying ways in which the U.S. government has counted Americans over time offer a glimpse into the country’s past, from the days of slavery to various waves of immigration. Racial categories have been included on every U.S. census since the first one in 1790. But they have changed from decade to decade, reflecting the politics and science of the times.

It was not until 1960 that people could select their own race. Prior to that, an individual’s race was determined by census takers, known as enumerators. And it was not until 2000 that Americans could choose more than one race to describe themselves, allowing for an estimate of the nation’s multiracial population.

Related: What Census Calls Us: Explore the different race, ethnicity and origin categories used in the U.S. decennial census, from the first one in 1790 to the latest count in 2020.

More than it has for any other group, the United States has revised the way it categorizes people who are racially both Black and White, reflecting the nation’s history of slavery and changes in the social and political thinking across time. In the mid-19th century, for example, some race scientists theorized that multiracial children of Black and White parents were genetically inferior, and they sought statistical evidence in the form of census data to back up their theories.

Throughout most of the history of the census, someone who was both White and another race was counted as the non-White race. In the 1850 census, enumerators were instructed to record Black people, “mulattos” (generally defined as someone who is Black and at least one other race), Black slaves and mulatto slaves separately.

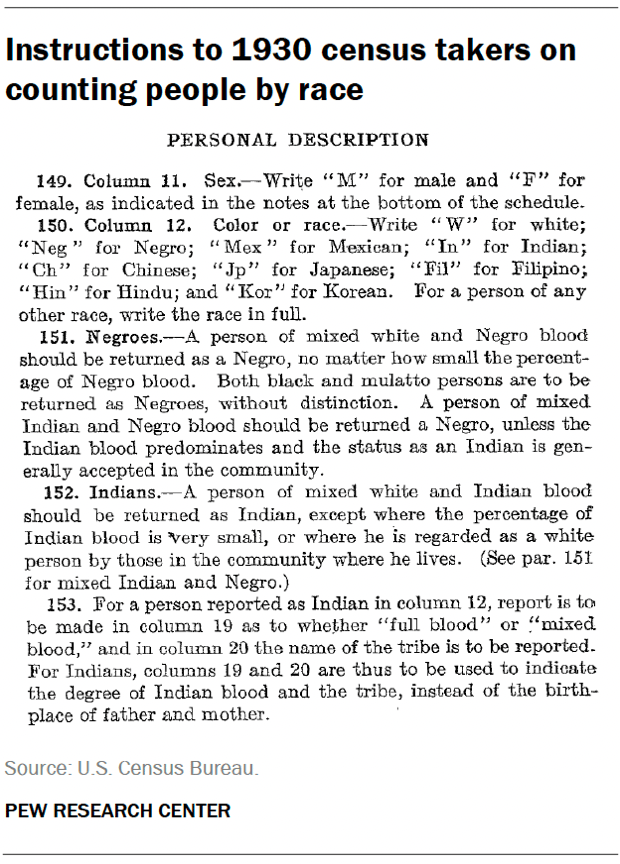

In 1890, the racial categories of “quadroon” (defined as one-fourth “black blood”) and “octoroon” (one-eighth or any trace of “black blood”) were introduced. In 1930, for example, the “one-drop rule” included in enumerator instructions said that “a person of mixed white and Negro blood was to be returned as Negro, no matter how small the percentage of Negro blood.”

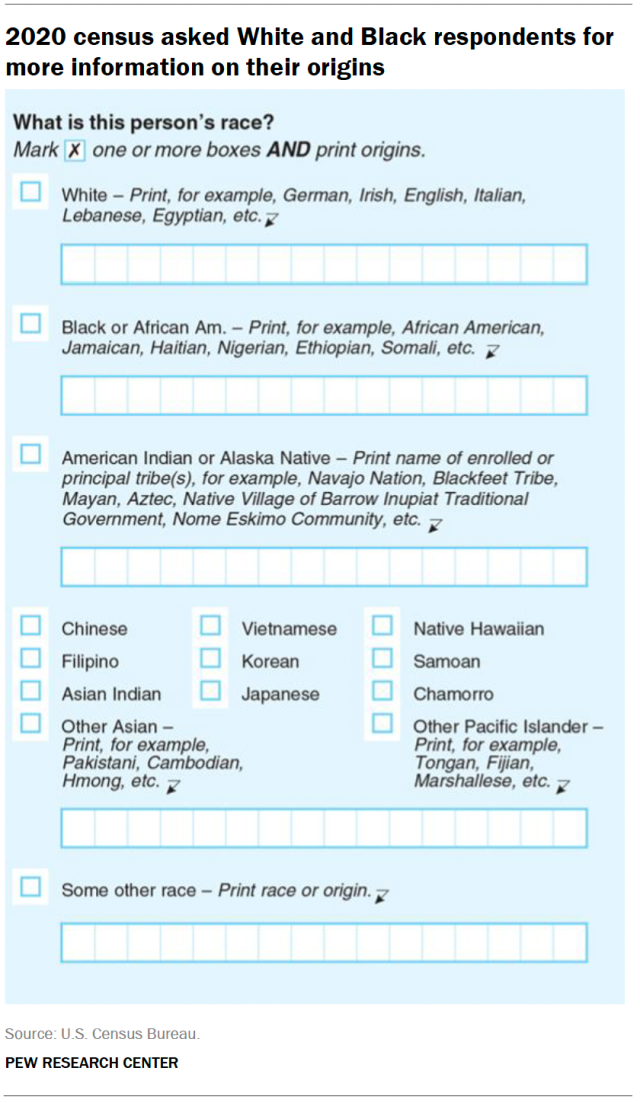

In the 2020 census, the bureau dropped the word “Negro” from what had been the “Black, African American, or Negro” response option.

American Indians were not identified as such until 1860, when the racial category of “Indian” was added. Beginning in 1890, the census included a complete count of American Indians on tribal land and reservations. In 1960, categories for Aleut and Eskimo were added in Alaska only. Since 2000, the category has grouped both of these together as “American Indian or Alaska Native,” and the census form provides a blank space to specify a tribe.

The first racial category for Asians was introduced nationwide in 1870 with “Chinese,” reflecting increased concern over immigration as many people came from China to work on the Central Pacific Railroad.

In 1910, “Other” was offered as a race category for the first time, but the vast majority of those who selected it were Korean, Filipino and Asian Indian. “Other” or “Some other race” was included on most subsequent questionnaires, encompassing a broader range of races, and the Asian racial categories were later expanded. Asian Indians were called “Hindus” on the census form from 1920 to 1940, regardless of religion.

Beginning in 2000, people could select from among six different Asian groups in addition to “Other Asian,” with the option to write in a specific group.

In various censuses between 1960 and 1990, the categories of Hawaiian, Part Hawaiian, Samoan and Guamanian were added and counted with the totals for the Asian population. Beginning in 2000, based on research conducted by the Census Bureau and new Office of Management and Budget guidelines, Native Hawaiian, Samoan and Guamanian became part of a new category: Pacific Islander.

“Mexican” was counted as its own race in 1930 for the first and only time. Hispanic groups of any kind were not offered as options in the full census again until 50 years later, when the census form began asking about Hispanic origin as a separate question from race from 1980 to 2020. (An experimental version of the Hispanic origin question appeared on the 5% form in the 1970 census.) Today, the form offers three Hispanic origin categories as ethnicities, along with “Another Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin,” with the option to write in a specific origin.

Combining the race and Hispanic ethnicity questions into one category is a change that has been under consideration for decades. In 2010, the Census Bureau began testing a question that merged the race and ethnicity questions into one, allowing Hispanics to select Hispanic as their race or origin. But the Office of Management and Budget, which has final say on what is asked in federal surveys, did not approve the change before the 2020 census.

In the 2030 census, however, the bureau plans to introduce a combined race and ethnicity category for the first time.

Related: Counting Race: How the Census Measures Identity and What Americans Think About It. Explore more on potential changes to the 2030 census and what the U.S. public thinks about the federal government asking about race.

Note: This is an update to a post originally published on June 12, 2015. After publication on Nov. 3, 2025, a new sentence was added Nov. 6 to address experimental Hispanic origin questions on the 1970 census.